Ambit valent.

Looking over the last entry in this occasional series I am, well, flummoxed; it’s a long and shaggy mess, isn’t it, and what I’d thought was the crux of it all—the omphalatic hinge?—got rather lost in all the noise.

—Probably doesn’t help that I hadn’t the faintest idea what that hinge even was until I’d written over half of it.

The which being: this whatever-it-is-we’re-pointing-to, this urbane phantasm, this lupily dhampiric gamine in an Eddi and the Fey T-shirt knotted up to show off a tramp stamp, this genre is essentially a superposition of two (to me) wildly disparate concerns, approaches, skillsets, Anschauungen: on the one hand, the broadly generalized concerns of what you might call primary world fantasy, where rather than haring off through wardrobes after magic rings beyond the fields we know, one seeks instead to take what wonder-generating mechanisms might readily be to hand and attach them however slap-dashily to real and concrete pieces of the world about us; tipping over stones and peering around corners and turning on lights after everyone else has left to show us the stuff we suspected but never believed could be true, not like that—the very general sort of thing any fantabulist worth their salt’s been getting up to for the past several centuries, made special in this particular only because so many of us here and now live in these relatively new things called cities; look! What changes might they ring on all the old tricks in our packs!

And then on the other hand, Anschauung no. 2: the fears where genre’s pooled: the prickly relationships now between power (and violence) and gender; the ways in which those relationships have changed suddenly, or how we’ve suddenly noticed they’ve been changing all along—or haven’t, at all, despite what you might think, might want, might hope—and how all those changes, or those things that stubbornly refuse to change, upset all manner of privileged applecarts and unsettle—make storyable—so much that we yet unthinkingly take for granted when it comes to power and gender (and violence); look! What changes this might ring on all the old tricks in our packs!

—Changes which have been happening (or not yet been happening dammit) in no small part due to these relatively new things called cities so many of us have been living in lately. I mean, you put it that way and all.

I’m left thinking—when I look at it this way, from this angle, with this set of vectors in mind (who was it who used to talk about how there were too many notes that had to be played but couldn’t be blown through a horn all at the same time so instead you play them one after another really fast instead, an allusion of chords? Sheets of sound? Was it John Coltrane? Yeah okay never mind), what I’m left thinking of (again) is the Engineer and the Bricoleur—the differences between coolly designing a system from the top down, and shaggily building a system from the bottom up; clean clear processes and principles thought through and carefully set down against solving the immediate problem that presents itself with whatever’s to hand and then up and on to the next—there’s a dizzying gulf between these two approaches, these disparate Anschauungen; it’s hard to keep the needs and goals of both in mind at once, and maybe this is why I keep flipping the coin over and over in my hand, startled every time the other, different side’s revealed—but look! It’s all one thing! And yet—

Probably doesn’t hurt that William Gibson has been twittering up the distinction between genre and narrative strategy that was I think made about him and his work by was it Dennis Danvers? I think? —And yes, it’s specifically SF-as-genre versus SF-as-narrative-strategy, but let’s pretend for a moment we can generalize it, unpack any intent from its strictures and look at each one by the other for a moment because this distinction’s gonna become important and you don’t want to be tripping over the furniture of swords and rings and rocketships when we abstract this shit up and out, and for fuck’s sake let’s all be as charitable as possible when regarding the connotative sneers that inevitably attach themselves to genre whenever it’s teased out like this; there’s some value to the exercise I think if we all keep our hackles down—ain’t nobody here Docxtrinaire, okay?

Where was I? —Genre, narrative strategy; urban fantasy; wonder-generating mechanisms, power and gender, sex and violence; cables and snakes and pythia. Right. —If one approaches urban fantasy as a genre, as a category fiction, as a transaction between a writer and an emergent and self-organizing audience with certain expectations that actively seeks out the sort of thing it likes because it likes that sort of thing; if one wishes to maximize the return (of enjoyment, of feedback, of reader response) on one’s investment (because who wouldn’t), one’s going to take a look around at what went on before to suss out the processes, the systems, the rules or at least the common threads before one sets out to build one’s own, and looking about one would see Buffy and Anita Blake and Mercy Thompson and Jayné Heller and Kitty Norville because there’s the bottle and there’s the lightning and one would be ill advised to push too far beyond (there are rules; there is a process; the audience likes what it likes and will tell you if you listen): and so one ends up with a Strong Female Character who deals with a supernatural intrusion either openly or clandestinely with some nominally masculine, appropriated power—a Phallic Woman, to put rather a fine point on it—and as one merrily sets about storying the hell out of a wonder-generating mechanism built along these lines, one can’t help but subvert and uphold, interrogate and reify all manner of gender roles and the power rules that they imply.

And if one instead approaches urban fantasy as a narrative strategy, as a way of generating story by taking up old wonder-generating mechanisms and plugging them into whatever relatively new bits of the urban environment present themselves to see what might happen, well: a great deal has changed over the years and so a great deal must be changed without changing too much at all, and that’s one of the challenges to be relished, but nowhere more than in the simple fact that we all see men and women and whatever différence might yet be vived very differently now than we did when the songs were first sung and the spells were first cast and the monsters first ripped from the dreams that spawned them, and one can’t be honest to the characters who find themselves in such a framework without helplessly being drawn back again and again to subvert all those gender roles and the power rules that they imply, and also to uphold them; to reify and interrogate them.

Whichever way you turn, they make the world go round.

(And oh but there are whole universes of discourse I’m glossing over here. Every nut-brown phouka in the room just cocked an eyebrow as if to say oh yeah, hoss? What about race? And I shake my head, later, later, Christ isn’t this all big enough as it is for the moment?)

So let’s not pretend this blurry, loosely drawn bivalent ambit is in any way either necessary or sufficient, but it’s nonetheless helpful (or why would I bother?). —One of the minor problems that has bedevilled me in skating around the problem of URBAN FANTASY (to turn the neon sign back on for a moment) is what’s to be done with Charles Stross’s Laundry books? Because he’s merrily attaching wonder-generating mechanisms to all manner of urban settings, and yet what he’s doing clearly isn’t URBAN FANTASY, as any fule kno. —And for a while there I was handwaving it away with muttered strictures about unity of place or somesuch; now we can all clearly see it’s because he isn’t taking up that other prong, of power and gender, because he doesn’t have to: his wonder-generating mechanisms are drawn from the chilly, post-Enlightenment well of Lovecraft. —And so.

From winter to winter again.

“…in that narrow world between the hills, she loved the river most. It is here and going elsewhere, like a story.” —Greer Gilman sings her mother on.

I’m trying, honest, I am.

“…if you’re not careful you will talk about it,” says Ray Bradbury. “Get your work done. If that doesn’t work, shut up and drink your gin. And when all else fails, run like hell!”

What we talk about when we talk about what we’re pointing to.

Urban fantasy as a subgenre usually has a little bit of hard-boiled noir action going on, blending fantasy with the elements of a modern crime story. Here’s a body, in other words, or some other horrible atrocity, and now here’s a hero/heroine with a special magical doodad/heritage who’s going to avenge/solve the crime. That’s the super-duper simple version, and the umbrella term can cover much more, of course…but that should get you started.

So, I am finishing up writing and polishing a YA novel that I thought was UF. But now I’m starting to think it’s not. By strict definition, it is. The MC and fairies having adventures around London. But as a marketing category, it seems like UF might not really work.

Under normal circumstances, it would be considered a straightforward Urban Fantasy/paranormal romance: independent, capable woman pits herself against the supernatural, meets up with mysterious wizard with dark powers and great cheekbones, and sparks fly, at least when Death isn’t waiting around every corner. You know, the usual.

After doing some research on the genre, I wondered if most urban fantasy fiction is in 1st person or you can get away with close 3rd with alternating POVs, corresponding with chapter breaks and/or scene changes.

Urban Fantasy is really bookcover-based, and as a genre is really a mashup of fantasy and romance novels, and we’re still sorting out the schizophrenia of clichés that this has produced.

And, sorry, I appreciate why you might want Urban Fantasy to mean what it meant 30 years ago, and you guys have perfectly good arguments as to why it should, but in common conversation it just doesn’t.

—Artw

Urban Fantasy seems to me to revolve around the uncomfortable relationship between gender and power.

If ten people are talking about urban fantasy, they’ll actually be talking about six different things.

Carrie Vaughn for the win, and not just because she’s written a neat overview of how the thing we pointed to when we said “urban fantasy” shifted and changed when I wasn’t looking into a bunch of other things pointed to by a bunch of other people. —“Urban fantasy,” of course, is a genre, and genera—whether we’re talking about the flavor-of-the-season catch-as-catch-can shelving categories of agents and sales reps, or the (somewhat) more considered taxonomies of critical apprehension—well, they’re social objects:

…those [objects] that, instead of existing as a relatively limited number of material objects, exist rather as an unspecified number of recognition codes (functional descriptions, if you will) shared by an unlimited population, in which new and different examples are regularly produced.

—And so while it’s possible to quibble and snipe over this trope or that and whether it’s really part of how you think the thing you think you’re talking about works at this precise moment in time and place in history, you should never think you’ve actually defined the thing in question, not necessarily, not sufficiently, not at all—it moves when you aren’t looking, shifts, changes; while you’re otherwise engaged, someone else points to something else entirely, and here we are left talking past each other, the ten of us, about six different things. —At least.

So what am I pointing to when I say—

Well, Christ, what is it I’m saying, anyway? Urban fantasy? Low fantasy? Modern fantasy? Syncretic fantasy? Contemporary fantasy? Indigenous fantasy? —Well much as my own finger might rather prefer contemporary fantasy (actually, my finger might best prefer indigenous fantasy, as suggested by Brian Atteberry: fantasy “that is, like an indigenous species, adapted to and reflective of its native environment,” but Lord does that fast become a problematic term)—I think it’s clear; the game’s given away: vox populi and critical weight and a couple of filips and grace notes we’ll come to all compel me to walk over here and sit me down under the blinking neon sign that says URBAN FANTASY.

Despite those wags who insist the “urban” must mean that Little, Big isn’t what I’m pointing to and Perdido Street Station is. It is; it isn’t; all of these terms have their problems, even the milquetoasty “contemporary.” —But it’s urban we’ve settled on; urban it is.

So that’s what I’m saying. What is it I’m pointing to?

At the end of the nineties I spent a lot of time walking from an office on Park between Washington and Alder to an apartment on the same block as what would later become Robin Goodfellow’s house at midnight, at one in the morning, at two. My route to avoid busy Burnside took me through what we were only just derisively starting to call the Pearl, through the heart of what would one day become the Brewery Blocks, when it was still, y’know, a brewery, and at midnight or one or even two the glass bottles would be clink-clinking together on the conveyor belt that ran overhead across the street from one stage of the brewing process, in that building there, to the next, in the building yonder. And somewhere on one of the corrugated metal sides of one of those buildings there’s this thing, and I don’t know what it’s called, but it’s where the main power line comes in and it comes down the outside of the wall in a sort of pipe that ends in in several up-curled snouts like horns from which sprouts a thicket of much thinner cables that branch out to carry the power off hither and yon throughout the building. And sometimes there’s one that isn’t in use anymore, so there’s no cables sprouting, just those horns, upturned, empty, waiting. And walking past at midnight or one or two I saw them and I said to myself, I said snakes, I said pythia, I said oracle—

—and there she stood all of a sudden, sprung fully if not finally formed into the pinkish-orange streetlight: this Lori Petty-looking kid with spiky yellow hair and goggles pushed up on her forehead and black jeans and a white T-shirt with the sleeves ripped off and mismatched Chuck Taylors with duct tape on the toe, and one work-gloved hand was on her hip and the other was holding a glimmering baseball bat, and she very obviously expected those snouts to turn and talk to her—

Kip, meet Jo; Jo, meet the author.

But that isn’t the point, that little where-I-got-my-idea moment, and anyway I’m lying about it. Just a little. You can’t help but lie about something like that when you set it down (and of course I warned you I would). —No, the point is the moment just before, the moment when the thing there on the side of the building shivered, or could have shivered, maybe, if the light had been right; when a wonder-generating mechanism of fantasy reattached itself however briefly to something any one of us could see out in the world: cables; snakes; pythia: not a portal opening onto some secondary world beyond the fields we know, but something indisputably here and now: contemporary; indigenous; syncretic.

The only reason it’s urban is because so very many of us who make it and read it these days live in cities. (Or suburbs, yes. Or exurbs. Urban. Look at the words.)

So that’s what I’m saying, and that’s what I’m pointing to, but what is it I’m talking about? Any fantasy which draws its sensawunda from the here and now? Because that’s awful broad, isn’t it? And there’s nothing at all in there about noir or crime or hard-boiling anything or vampires or dhampires or werewolves or witches or undone leather pants or tramp stamps or cheekbones or a close 3rd with oscillating POVs or well anything specific, you know? —Yes, yes. And no, I’m not talking about something that impossibly broad. I mean, it’s definitely a thing, it’s a valuable distinction, but it’s an awful big circle on any Venn diagram you’d care to make. We should maybe focus. Look more closely where we’re pointing. Keeping in mind of course that nothing we say can ever be necessary or sufficient enough to define what it is we’re talking about, so we’re just fucking around, right?

So if we take a closer look say at Enchanted—

Yes, Enchanted, the 2007 Disney flick about the animated princess who falls through a manhole into 21st-century New York City—

Yes, it’s an urban fantasy.

Look, just watch this, okay?

See? Urban fantasy. —No, not because it takes place in a city. Not just. But because it takes something particular to a particular city—no, not busking, or not just busking, but—well, watch this—

I mean, this shit really happens in New York. The spectacular busking, the audience participation, the spontaneous musical numbers, the sort of moment that just doesn’t happen, not in the same way, in Harvard Square or on Maxwell Street or Pioneer Square or wherever it is in London that busking goes down. —And granted, Central Park isn’t usually full of pre-rehearsed Broadway players between roles, but that’s just part of what makes the movie moment transcendent (and scoff if you like, but silly, and overblown, and swooningly earnest, these things all transcend)—thus magical, thus fantastic, but a fantastic moment grounded and rooted in a very real place we all know or at least can get to, not just drawn from but indisputably of a very particular here and now. —Wonder, however clumsily, reattached.

(It works the other way round, too. —I read Folk of the Air years before I ever flew down to the Bay Area and rode BART out to North Berkeley and when I got out of the train and stood on the platform and looked around and the way the light soaked the air without ever quite falling and the dark hills over there and all the water that you couldn’t see left me stranded in Avicenna for a long and dizzying moment instead, with Julie Tanikawa about to ride by on her big black BSA. —The indisputable here and now, without warning, reattached to wonder.)

But remember that none of this is necessary to define what it is we’re talking about—Bordertown is urban fantasy beyond the shadow of a doubt, and yet rather firmly takes place in a city that doesn’t exist, or rather (and this is the key, though it’s still off thataway, on the edge of the fields we know) it’s variously every city the authors see it as and need it to be, patchworked, multivalent—nor any of it sufficient to so define. (So why are we talking about it? I don’t know. Passes the time?) —When I started thinking about these posts and this one in particular I figured I’d stop here, you know, rough out the idea that what I was pointing to when I said “urban fantasy” was anything of the fantastic in an otherwise recognizable place, and then I would’ve backed off and tried to knock that over from another angle, see what happened when it broke.

But that isn’t it, and it isn’t sufficient. It isn’t even a genre, not yet. It’s—an idiom, a loose collection of tropes, windowdressing; it’s too clumsy and loosely fitted a tool to use for any close-in work. (Hell, you could fit great steaming chunks of magic realism in that definition, and I think we all know that’s not right.) —So: more focus, more specificity, more—noir? More boiling? More cheekbones? More leather? More Glocks?

I mean I started kicking this around because it seemed to me there’d been a divergence between old skool urban fantasy and the paranormal romance that lines the supermarket shelves these days; because saying to myself that what I wrote was urban fantasy meant trying to imagine what Jo Maguire would look like in leather pants on the cover of a book her tattooed back to us all (and then bursting into laughter; “I thought it was UF, but now I’m starting to think it’s not”); because I thought I saw ways that television and comics and role playing games had helped shape and widen that gap, which fascinated me, and anyway I’m a sucker for roads less travelled and not taken. So I set up my oppositions and sketched out the common ground and started doing the spade-work necessary to figure out exactly which term I preferred and whether I agreed that indigenous fantasy is essentially a rhetoric of intrusion or immersion and while I was dithering about Daniel Abraham went and said, “Genre is where fears pool—”

—and see that’s what’s missing from what I would’ve been talking about, that’s why what I’d had in mind as common ground wasn’t a genre any more than SF is a genre, or fantasy, or superheroes. Genre is where fears pool. It’s the immediacy, the kick, the redlining engine that doesn’t leave you the luxury of looking back and seeing what you just ran over, and urban fantasy, says Daniel Abraham, seems to him to revolve around the uncomfortable relationship beween gender and power—

And that certainly isn’t sufficient, no, and it isn’t necessary either but nonetheless watch it all slide and slip and snap quite suddenly into place, Anita Blake and Buffy and Eddi and Farrell and Doc and Oliver and one could even start reaching down for some of the dimly glimpsed taproots like Conjure Wife and hey, like I said, there’s Enchanted at the other end with some self-consciously conversed Disney platitudes about princesses saving the day.

But that’s heady and it’s late and I’m dizzy and this has gone on long enough for now. I want to back up, come at this ungainly construct from another angle, try to knock it over. See what happens when it breaks. And anyway I think I need to take up Clute next. —So.

Further up; further, in—

But! Baby steps. Easing back into it and all. —Maybe the business with the maps?

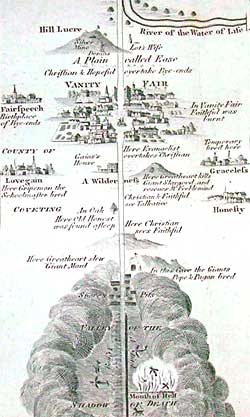

The portal quest fantasy, per Mendlesohn (as opposed to an immersion, or an intrusion, or a liminal, or whatever else, and trust me, we’ll get there), is a didactic idiom: one that takes its necessarily naïve protagonist on a tour of the otherworld with a garrulous guide or guides who brook questions almost as often as interruptions. “Fantasyland is constructed,” she says, and we should be clear, she means Fantasyland is constructed in the portal-quest fantasy,

in part, through the insistence on a received truth. This received truth is embodied in didacticism and elaboration. While much information about the world is culled from what the protagonist can see (with a consequent denial of polysemic interpretation), history or analysis is often provided by the storyteller who is drawn in the role of sage, magician, or guide. While this casting apparently opens up the text, in fact it seeks to close it down further by denying not only reader interpretation, but also that of the hero/protagonist. This may be one reason why the hero in the quest fantasy is more often an actant rather than an actor, provided with attributes rather than character precisely to compensate for the static nature of his role.

Which, okay, and now let’s skip ahead a couple of pages—

This form of fantasy embodies a denial of what history is. In the quest and portal fantasies, history is inarguable, it is “the past.” In making the past “storyable,” the rhetorical demands of the portal-quest fantasy deny the notion of “history as argument” which is pervasive among modern historians. The structure becomes ideological as portal-quest fantasies reconstruct history in the manner of the Scholastics, and recruit cartography to provide a fixed narrative, in a palpable failure to understand the fictive and imaginative nature of the discipline of history.

Flip back a page or two—

Most modern quest fantasies are not intended to be directly allegorical, yet they all seem to be underpinned by an assumption embedded in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678): that a quest is a process, in which the object sought may or may not be a mere token of reward. The real reward is moral growth and/or admission into the kingdom, or redemption (althouh the latter, as in the Celestial City of Pilgrim’s Progress, may also be the object sought). The process of the journey is then shaped by a metaphorized and moral geography—the physical delineation of what Attebery describes as a “sphere of significance” (Tradition 13)—that in the twentieth century mutates into the elaborate and moralized cartography of genre fantasy.

—which paragraph ends neatly enough with—

In any event, the very presence of maps at the front of many fantasies implies that the destination and its meaning are known.

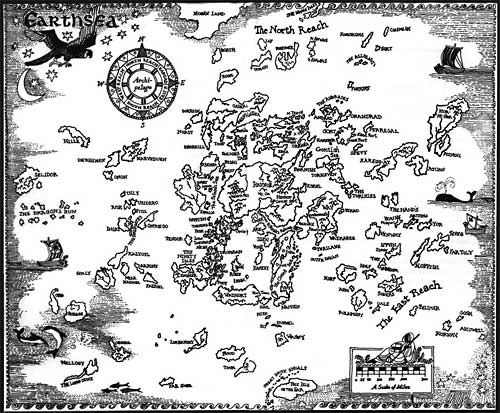

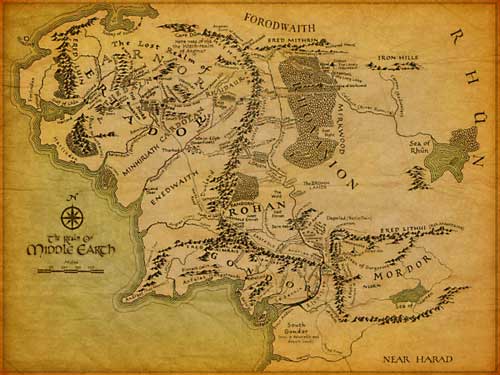

—and, well, yes, okay: I mean, you open just about any wodge of extruded fantasy product these days and yes, there it’ll be, the map, or at least it used to be that way; maybe it’s fallen out of fashion these days? —Doesn’t matter. The ghost of it’s damn well there. There’s always been a map.

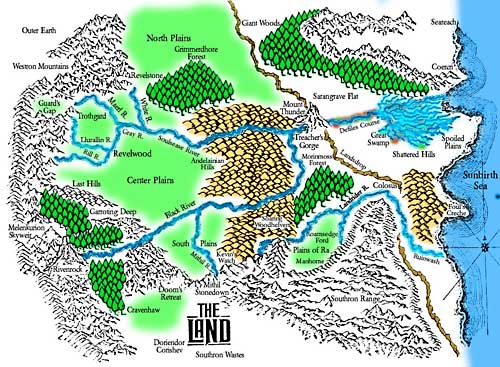

And maybe it isn’t too clear, immediately, on the map in Papa Tolkien’s tome, how the process of the journey is laid out, how it is exactly the geography’s metaphorized and moralized. But pull out some more maps, pore over them, look at how the Skull Kingdom’s always behind the Knife Edge Mountains—

—how the Soulsease River flows through Treacher’s Gorge and Defiles Course into the Sunbirth Sea—

—and you can start to see it; look more, look further back, scrub away the distractions of mountains and trees and lakes and look just at the map itself—

—and you can start to see the sphere of significance plain and clear, on which then the story of the quest of our hero(es) can be, well, mapped—

—a bildungsroman unspun in space, not time. You will go here, and have this adventure; go there next, and meet this companion; you will face physical hardship in the mountains, then inner turmoil in the deep woods, and if there’s a city, there will almost always be a seige, and a tower, and a coronation. Go and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again, and keep what you know of the story (of story itself, even) in mind (you know the story; the thing about this sort of thing is you’ve yes always already known it), it becomes clear that the destination and its meaning are known, are written there before you, that there was only one way it could ever have ended, once you started in the bucolic upper left; you had to sweep down and down to those snarling mountains in the lower right, and the city of Gondor gleaming there, where you might find your reward. —Didactic, fixed, moralized, metaphorized; cartography has been recruited, yes yes.

But—

Maps were my protonovels. I was reading Tolkien, and it was the maps as much as the text that floated my boat.

Mendlesohn, and this is important, is describing an effect of the rhetoric of the portal-quest fantasy. And it is a terribly important and I would even say o’erweening effect; she is not wrong to highlight it and draw protective circles about it thrice and thumb its forehead with penitent ash. The didacticism, the storyable past, the moralized geography, the protagonist as actant, the you-must-do-as-you-are-told-to-save-us-all (to reach the Celestial City, to redeem yourself)—this (if I might stuff it all into a singular word) is the supreme weakness of the portal-quest, and because the portal-quest is even now the supreme idiom of fantasy, is even now all of what most of us know of fantasy at all, this effect she’s described must therefore be addressed one way or another by every phantastickal book on the shelf.

But it’s hardly the intent of the naïve protagonist, the travelogue through fantasyland, the expository wizard, the map on the frontispiece. —Nor is it anywhere close to the only effect this furniture, these bits of business, might have on the reader, and the reading.

I’ve embedded images of these books because they offer, in various ways, some of the visual appeal which takes hold of readers of LOTR, The Hobbit and so on; Tolkien was susceptible to the paraphernalia of scholarship, to maps, manuscripts, the annotations which triangulate desire on such artifacts as objects of retrospection to a more heroic time—one constructed as real through the survival of such relics. For a certain sort of reader, scholarship is glamorous because reinforcing l’effet du réel.

The intent (an intent) is to take us readers by the hand and lead us from the world as it is out and away beyond the fields we know, and the simplest, easiest, most direct way to do this is to put fantasyland Out There and lead us through it, dragged along behind a protagonist who doesn’t know much more than we do, who must have stories told to them (and us) about the things they see, and because we are traveling about together in this other world, well, why not a map? That artefact of traveler’s journals ever since travelers began keeping journals. (Did every traveler keep a journal? I mean, all of them? How long ago did they begin, anyway? Were they really journals, or were they more reflections written long after the travels that spawned them? Or, y’know, propaganda, or marketing collateral, or—)

—To insist that history is multivocal, is an argument to be taken up and not a story that is dictated, is, well, is correct; to castigate this simple, brute-force technique for lulling a reader into the fields beyond as not living up to this basic truth of how we know what it is we know is, well, is also correct—but it overlooks the fact that the many and varied voices that carry out this argument of history, these arguments with history, are carried by books upon books within books echoing off books.

Most fantasylands are lucky to get just one.

And this is not an excuse, no. But it is a way out of the supreme weakness hobbling this idiom supreme: there’s absolutely nothing to prevent a writer from taking a protagonist and the reader bobbing along behind through a portal and on a quest that traverses an argued, arguable fantasyland, one where the questions one asks of the garrulous wizards, the interruptions one makes in the stories they try to dictate, are themselves important bildungstones, are themselves crucial steps on the road to the Crystal City of redemption and restoration.

(The trick of course is that the bedrock grammar of fantasy—that’s Clute, we’ll get there, trust me—would set you on a road to redemption and restoration, which irresistably implies that the questions asked will ever have final, true, correct answers; if you aren’t careful, you’ll just end up shifting the mantle of diktat from garrulous wizard to impertinent protagonist. —I never said it would be easy.)

But even if one doesn’t, even if the book one is reading hasn’t come anywhere near this ideal, well: it’s still a book. And the street will always find its own meanings in books. The most univocal, didactic, imperiously railroaded books can’t help but be polysemous; for fuck’s sake, they’re books.

And as for maps—

Recruit them all you like. Metaphorize and moralize until the very tectonic plates groan beneath the weight of your intentional fallacies. Make the road from Here to There through those Fields Beyond as straight and clear a track as you like. The thing about maps is no matter how simple or naïve they are they can’t help but hold more than you put into them. It’s the nature of maps. Even if it’s just the words Here there be Dragonnes. —Even if it’s just blank space surrounding the railroad track you’ve laid! Hell, sometimes blank space is the most evocative of all.

Go back and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again—

—and forget for a moment the too-obvious sweep of narrative laid out before you from Eriador through Gondor to Mordor. Haven’t you always wondered, lying on your stomach, map unfolded carefully carefully from the endpapers and laid out on the carpet before you, haven’t you always wanted to know what the beaches of the Sea of Rhûn were like, this time of year?

So. Yeah. Maps. Or anyway an intemperate discourse spawned by an offhand remark about maps, and their use and, well, misuse.

Baby steps. —It’s a start.

I’m going to leave you with one more map, an ur-map, if you will; the map, really, of fantasyland as she is wrote, or at least as I’m going to be playing with it for a bit, here:

Of course, a map really benefits from having a key. —It’ll come.

The Great Work.

The time my mother slapped me?

I was a junior in high school. Seventeen? Maybe. I don’t remember what it was I wasn’t to be allowed to have done, but I was complaining about it, bitterly, vociferously, rounding it out with the rising plaint of it just isn’t fair!

Life isn’t fair, she said, exasperated.

That’s no excuse! I snapped.

Pop!

What underpins all of the above is the idea of moral expectation. Fantasy, unlike science fiction, relies on a moral universe: it is less an argument with the universe than a sermon on the way things should be, a belief that the universe should yield to moral precepts.

Which isn’t what happened at all. —Oh, I was complaining about something; I was a teenager. And she’d told me more than once (but not that much more) that life just isn’t fair. And I wanted to say something in response, of course I did; I was a teenager. But if I ever managed to mutter anything at all I doubt it was so pithy. No, the time she slapped me I don’t even remember what she said, or I said. I just remember standing there, in the kitchen of the farmhouse outside of Chicago, the sting, the vague sick flutter in my belly and the half-swallowed grin of embarrassment, the acknowledgement that you know I’d probably deserved what I’d just got, but.

So I lied, just now. —But you know what they say about writers.

I’m not about to talk about it over there; over there, there’s whole words I can’t even spell out for fear of breaking—something. (Like the song says, as soon as you say it out loud they will leave you.) —But I have to talk about it somewhere. When I started to write it it was ten years ago and what we called the thing it was then was completely different than the thing we call by that name now. Used to be it was Eddi and the Fey concert T-shirts; now it’s tramp-stamped werewolves, and is that a bad thing? A good thing? A class thing? A get-off-my-lawn thing? Actually maybe not a different thing at all? —I don’t know, but I think maybe something got written out from under my feet, and it might be a good idea to figure out what it was before I land.

—And also there’s Mendlesohn, and Clute; Clute and Mendlesohn.

Which is not to say they’re wrong, my wanting to hash it all out like I want to. I mean, of course they’re wrong; they’re working with models. All models are wrong. But some are useful, and I haven’t yet figured out whether, or which.

Hence, the Great Work. Limned and primed.

Things to keep in mind:

The secret of courtesy.

“—I imagined that a man might be driven to despair by all the ugliness he had seen and want to see some unprompted dazzling act of goodness. I think this may not have been right. What I find is that if you deal with bad people for long enough you treasure even trifling acts of courtesy. If I go to a café and order an espresso, I’m charmed, disarmed, speechless with gratitude if the waitress brings an espresso.” —Helen DeWitt

“You can tell him by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that sooner or later he brings up the Templars.”

So, right: the default response to a post from John C. Wright, then, turns out to be exactly the same as the default punchline to a New Yorker cartoon. (—And I have to keep reminding myself: this is from the intellectual end of the rump.)

The hairs of my chin bristle as I repeat it, silently—

Autumn Fugue

A book was sometimes held in your hand

when the Committee on Understanding met

as you waited for them to call you in

& the man who mowed the graveyard

waved with a circular wave

in the manner of cousins under the elm

where it seemed sweet spices

had been cast down near accordion streets

so once the small democracies

had begun, time could make an exception

for owls with the faces of seeds

that looked just like themselves only open;

it is late & sweet with a late

democratic sweetness when seeds

had been cast down in the manner of

spices, where once the small committees

had begun, time played accordion

with its foot in the door, & you felt

at ease in a circular way

so even had the parties called your name

you would not have been wrong;

the elms had made an exception

& a book was sometimes found in your hand

that looked just like itself, only open—

For DY

Cochliomyia hominivorax delendum est.

How’s that for eliminationist rhetoric?

I feel vaguely guilty, making such a deal of accepting John C. Wright into my life. After all, what’s he done since then? A turgid apologia (i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi) that in no way indicated he’d thought at all as promised on what the Elders of Sodom had wrote, and an all-but-unreadable screed against empiricism (I think): Neo cannot say why he chooses to fight, and thus homosex is wrong, quod erat dammit. Overall a disappointing performance I must say.

—And then John H. Richardson has to cast a chilly pall over the whole enterprise anyway by going and talking to Mike Austin, an eighth-grade teacher in Oklahoma who until recently was saving the world one essay at a time over at the Return of Scipio.

Yeah, that Return of Scipio. Took me a minute too.

And Richardson has a lovely conversation or two with Austin, who seems a much nicer person than the Scipio Resurgent, much I’m sure as John C. Wright is much nicer than ![]() johncwright; he seems a hale enough fellow, I suppose, who could essay a hearty laugh—but that’s just how it works. Most of us are better than our manifestos.

johncwright; he seems a hale enough fellow, I suppose, who could essay a hearty laugh—but that’s just how it works. Most of us are better than our manifestos.

But still and all:

As we drive back to my hotel through the clean wide streets of Oklahoma City, I take a chance on some gentle teasing: “Everything’s so well-groomed, you got no garbage, no graffiti—I do not see the collapse of American civilization here.”

His answer comes out cold as a can from a Coke machine: “If you were to look at the streets of Nazi Germany in 1936, they would appear a lot like this. Probably cleaner.”

I’ve heard this exact argument before, from the Glenn Beck follower types, but I can’t believe they really mean to compare their fellow Americans to the most cold-blooded killers in human history. It must be rhetoric. They can’t be that alienated from the society that has given them, beyond any civilization in history, lives of such extraordinary privilege and comfort. My voice rises with my exasperation. “You could say that about any town anywhere!”

His answer comes back steady and patient, like he’s explaining history to one of his eighth graders. “The government in Washington, DC has encroached so much on states’ rights, it seems like we don’t have a federal system any more, rather an imperial one. And when the states lose their rights guaranteed in the Constitution, then what you have is tyranny.”

Obama is a fascist, he continues. Setting the limits of investment-bank incomes and claiming the right to seize General Motors are just two examples. Where in the Constitution does it grant him those powers? Are we a nation of laws, or is this a lawless regime that sends out its goons like Mussolini?

(And there it is, the voice of the blog: What has always stood against lawless men? Force. That is the only idiom understood by such men. To answer lawless men with force is to speak their language.)

[…]

“There are things worse than violence, John,” Austin tells me. “Slavery is worse than violence. The most peaceful place in the world is the cemetery.”

It is really a quite serious matter that the right-wingers have gone around the bend and apparently aren’t coming back…

There’s a new outfit in town—

—whose name’s suggested perhaps by all the glittering potentates who came to do homage to the aforementioned Elders of Sodom on receipt of their open letter to Wright. The basic mission statement for members reads as follows:

As a member of the Outer Alliance, I advocate for queer speculative fiction and those who create, publish and support it, whatever their sexual orientation and gender identity. I make sure this is reflected in my actions and my work.

This first of September, the Kalends of Sextilis, they’re asking for a show of hands. They suggest a link to fiction which is in any way on mission, and while there’s this or that I could point to, there’s also this or that game I don’t want to give away, and so instead I’ll highlight an old series of posts:

It’s how I started swatting at screwflies, anyway.

John C. Wright will of course forever be known for or at least in light of his hatred of homosex, but for all that he can’t bring himself to wish for the destruction of its practitioners, adherents, and supporters; at worst, we all get to sit in closets again, as Morality ever-so-passively just somehow returns. —Mike Austin, the (former) Scipio Resurgent, is at once more cosmopolitan and strict (then, Scipio was famously Græcophilic), but even he can’t bring himself to take the action he seems to think is vital; can’t help but laugh with the mainstream media man who’s come to talk to him; can only lash out at abstract ideas that have never set foot in Oklahoma or anywhere else. —They may have gone around the bend, but there’s enough shame yet to prevent them from actually advocating the clear, precise, destructive, eliminationist praxis needed to bring about the world they think they want.

And where there’s shame, there’s hope?

Room enough, anyway, for words: and enough of them, from stories told, from lives lived, from experiences actually had, will always outweigh an argument merely propounded.

We’ve always been better than our manifestos.

John C. Wright is recoiling in craven fear and trembling, and I don’t feel so good myself.

Actually, I don’t know that he’s necessarily recoiling in craven fear and trembling. But: he has taken down his storied post, “More Diversity and More Perversity in the Future!” in which he excoriated the SyFy [sic] channel for “recoil[ing] in fear and trembling when lectured by homosex activists,” after said post received 800+ lecturing, hectoring comments; and besides, I can never pass up an obscure joke.

I’ve been going by his LiveJournal every night now, ever since I caught a link to that rant (via the Mump), and I figured out this was that guy who wrote those books I’ve never quite gotten around to picking up—and now I can’t tell whether I’m glad I dodged a bullet, or whether I wish I hadn’t.

Tonight, after nuking the aforementioned storied post, he (in the course of defending his apology) posted the following:

First let us clarify who the enemy is. It is not the homosexuals. The enemy is the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) that are devoted to a Leftwing antinomian agenda, and willing and eager to use pressure tactics to enforce the doctrinal conformity so near and dear to the heart of the Left.

Which is me giving you the full context of the paragraph, and not the experience of reading it; the experience of reading it was rather more like—

The enemy is the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) that bleep! does not compute

When I found my jaw and resettled it on my face I found myself nodding along—well, yes, in a world in which the homosexual lobby is for the most part comprised of happily married heterosexuals, well, sure, perhaps there might very well be something sinister about their devotion to an antinomian agenda. —That our world, the world in which both I and John C. Wright unarguably exist, does not in any way resemble this world does not in any way invalidate the logic; merely the premise.

Sorry. Jaw’s still a little loose. —There.

I tried to post a comment. I was going to quote the bit about the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) and I was going to ask whether I might ask how he came by this particular fact. But he’s locked down comments to his LiveJournal; only those he’s added as friends are allowed to comment at all. The rest of us are banned.

Can’t say I blame him. The shitstorm was mighty. Battening the hatches is only rational.

MacAllister and I have not exactly been arguing or even discussing but more like honing points off each other. I’m going to quote hers first because it’s my blog and I get the last word, and I’ll grab hers from this tor.com thread:

I think we cannot conflate the art and the artist.

Actually, what I think is more vehement than the above statement.

In 1953, Isaac Asimov called SF “that branch of literature which is concerned with the impact of scientific advance upon human beings” and I find that description compelling precisely because so much of the impact of science upon human beings has precisely to do with issues that, once upon a time, were dictated to us by shamans, holy men, or chicken entrails.

I think it’s damaging to conflate the art with the artist. The writer is not the book. When we’re talking about the literature of ideas, especially, I think it’s damaging to us as thinkers, readers, and writers to artificially and arbitrarily shield ourselves from ideas we disagree with, find unpleasant, or even repugnant.

And there is nothing in that I do not agree with, but—and I’m going to grab mine from a whiles back when the Islets of Bloggerhans were talking about Orson Scott Card again because, you know, not inappropriate:

Science fiction is largely a fiction of setting: the bulk of the iceberg that’s unseen, underwater, is the act of world-building, and in that act, politics is paramount. (One is building a polis, after all.) —Therefore, it’s all-too-appropriate to keep in mind an author’s politics when considering their science fiction: an author who, say, considers homosexuality to be an aberration, is un- (or perhaps less) likely to build a world that would appeal to a reader who does not. There’s an assumption clash: one of his fundamental, foundational bedrocks is abhorrent to me, and vice-versa.

One can respond: well, yes, but there’s nothing about aberrant homosexuality in Ender’s Game, so how can it clash? Heck, there’s nothing in that book about homosexuality at all! And I will resist the urge to say oh, you think so? and I will even resist the urge to say precisely! —Instead, I’ll allow as how there’s frequently large gaps in the jerry-rigged polis left as exercises for the reader: one can hardly describe every kitchen sink, after all; one must make assumptions, and count on the reader doing likewise (which among other reasons is why fan fiction [and slash fiction] is so popular in science fiction). But that’s precisely why when those assumptions suddenly clash, it’s unsettling, even violently dissonant.

Which is why it’s not an argument and hardly a discussion. I’m talking about why I’m no longer terribly interested in reading Card’s work, nor Wright’s; she’s talking about why such work must remain available to be read. —A book doesn’t always have to be an axe for the frozen sea within, for God’s sake, but one should never lose the ability or God forbid the inclination to read for the hacking. But when the only challenge a book’s likely to pose is the challenge not to throw it across the room—

Why’d this come up in the first place? —Most of the 800+ comments to that storied post were along the lines of “I’ll never read your books again, thanks for warning me off, you’ll never get dime one of my money.” (“Every time you bloviate offensively on the internet, a reader swears off your work for life,” says Catherynne Valente, in one of the many open letters to Wright that have sprung up of late.)

Now, there’s a difference between “I do not wish to read you, or support you with my money,” and “You should never be published ever again!” though I can appreciate how it might be a difficult distinction to make on the receiving end. Especially when it’s more overtly couched as a boycott: “I’m never buying a Tor book again so long as they keep publishing writers like you.” (I’m sure John Mackey can sympathize.) But there’s also a difference between “You should never be published again!” and “I’ve fucking had it with living in world where you and yours make the rules!” —And I think what it is is my Emma Goldman baseline’s not wanting to be part of a revolution that depends on shutting people up.

Even if one of the ways I try to keep my little corner of the world safe from them and theirs is to, you know, not bother to read works by this author or that.

Barry and I were emailing about Wright and Card and suchlike. “Ah!” I said at one point. “Sitting in judgment of other people with my morning coffee on a chilly day off from work with a baby in my lap. —Have I mentioned how glad I am she’ll grow up in a world where these moral monsters are marginalized? Have I mentioned how terrified I am I’m wrong?”

That initial, storied post is an ugly thing, a ham-handed attempt at excoriating the SyFy [sic] channel from an infantilely Manichean lex naturalis, full of the sneering braggadocio of a playground bully preening for his sycophants (says me, with a sneer). —His basic argument (expounded in a later comment to that post) was a syllogism in Camestres:

Odd as it sounds, I was fully loyal to the sexual revolution as an idea. Then someone tried to convince me that two lesbians licking each other in the crotch was the same in all ways, just as sacred, just as romantic, just as normal, just as beautiful as Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Iseult, Micky and Minnie, Adam and Eve, Jove and Juno, Father Sky and Mother Earth, me and my wife.

(Or Ruth and Naomi? says me, preening.) —And yes, the premises fall apart in your hand when you gingerly try to pick them up, but yes, it’s a just-so story, and thus irremediable to them what believes. What’s striking is the ugliness of the language, the revulsion, the almost-desperate hodgepodge of totemic icons thrown up in defense, all in an argument that insists on the rigor of its logic, on the intractable ad hominemity of the other side. It seems to have struck Wright, too:

I think my posts were accurate but were not measured.

Let me give you a hypothetical:

Imagine standing in the waiting room of a hospital, and overhearing a doctor joking with a nurse about some patient about to die, and the doc uses gross slang to describe the patient’s bowels dissolving and so on—and you realize that patient is your loved one.

Now, the doctor said nothing untrue, and he was engaged in what actually he thought a private conversation (even if it was in a public spot). But you would be shocked, and he should be careful of your feelings.

And—well, yes, the analogy’s strained and rather terribly objectionable, but the basic sentiment, the apology itself, that’s sound enough, surely? Commendable, even, in an internet where no one ever walks anything back ever? (Though it’s with a poor and a threadbare, sketchy grace: “I had damn well better offer these people, enemies or not, the olive branch, and quickly. They will not accept it, if I am any judge of character: indeed, they will take it as a sign of weakness and redouble their efforts. But that is not my concern and not the orders I was given.”)

Except—the “you” above is a very particular, rather singular you, with a very particular and singular loved one who’s about to (figuratively) die:

There was one commenter whose feelings I actually hurt. His mother is a homosexual, and he was rightfully offended at the language I used to describe homosexuality. Him I apologized to privately, but I would also like to do it publicly. It is hard to tell, just from reading words, when people are being sincere, and when they are not, but I thought this one guy was sincere, and that most of the rest of you were engaged in rhetoric.

To him, wherever he is, I am sorry. I regret my words, and I regret my thoughtlessness. Please forgive me.

—And the queerly thrilling horror that’s been creeping over me the past few days comes sharply into focus, with all this talk of a monolithic Left and their antinomian agendas and a homosexual lobby filled with heterosexual couples and a straight Sappho and the evil space monkeys: he literally does not realize that every single person who snapped at him in the 800+ comments left on that storied post, every single one, was reacting out of anger that had come through grief, was just as rightfully offended by the language he’d used, was no matter how rude in response just as deserving of apologies both public and private, that each of them was or loved or knew someone whose life had been bent or broken or wrecked or deflected by the appallingly arbitrary rules he was defending, his dreadfully unnatural lex naturalis—

Yeah, but I wasn’t going to do, well, that.

This was about—what, exactly? Grace, yes, and the koan; trying to get past the two-minute hate—I did say it was anger that came from the grief, and did allow as how the responses were rude (and got my own licks in: “Shorter Wright: My sexual peccadilloes are moral imperatives; your sexual peccadilloes are suspect; their sexual peccadilloes are disgusting”—hardly one of my finer moments)—but trying to make a point of how maybe one should listen to an objectionable author just as one might listen to their works, when really you’re more than ready to sit in judgment on a chilly August night over a splash of bourbon, is just as chary as offering up an olive branch you’re ready to snatch back at the first rebuff. —And there’s more than a little disaster tourism in all this, too, which I realize mucks up the clarity of that up there, but none of our motives are ever pure.

And maybe if I did get a chance to ask him directly how he came by the striking notion that the homosexual lobby are for the most part happily married heterosexuals, he’d just tell me that by “homosexual lobby” he meant, of course, the monolithic Left, and as homosexuals comprise a minority of the Left much as they do the population at large well QED, but maybe he wouldn’t; I don’t know. There’s a herky-jerky searching quality in all the self-serving bluster that, well. Doesn’t so much fill me with hope. But it’s certainly captured my attention the past few days.

Or maybe it’s just I have a weakness for pompous brio. —Whichever; anyway, tonight I added John C. Wright as a friend over to the LiveJournal.

(Oh, I added Catherynne Valente, too. After all, her baseline work for the bare minimum hit of the stuff she’s jonesing for, for which she’d forgive an artist just about any asshattery, is Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale—and what are the odds? So’s mine!)

μῶμος.

At the age of 15, Humperson ran away from home to become a lighthouse keeper on the rugged, storm-lashed Atlantic coast. During this time he worked on a new signaling system intended to warn sailors of the various complex dangers—extending far beyond mere storms and rocks—presented by the sea. Unfortunately, because of widespread unfamiliarity with the system amongst sailors, wrecks were caused and a great many lives lost. Humperson fled to Jerusalem, where he studied anthropology and sociology in Hebrew under Martin Buber.

It was here—swatting flies in the fierce Palestine sun—that he began to develop the ideas for which he’s best remembered. Later, as a tenured professor at the University of San Marino, Humperson developed these preliminary insights into the five Laws of Meta as we know them today—

Momus extols an uncelebrated thinker.

Crap.

Saw this taped to the back window of a Suzuki on the way into work, not so much a bumper sticker as a placard—

A government big enough to supply you with everything you need, is a government big enough to take away everything you have…

—Thomas Jefferson

And I hope your nose wrinkled as immediately at that as mine did: I hope the horrid clanging dissonance between the words spoken and the speaker putated, in language, in political and historical consciousness, in punctuation, struck you as hard and as fast as it did me. “Bullshit,” I snarled, with perhaps more vituperation than was absolutely necessary, but commuting makes me cranky, and anyway he was driving like a dick.

But, I thought to myself mere moments after the outburst, is it really? —Bullshit implies some awareness on the bullshitter’s part of the truthy nature of one’s utterances. If one were in the course of a heated discussion on the un-American nature of single-payer health care to suddenly bust out with “Oh, yeah, well I think it was Jefferson once said that a government big enough to yadda yadda” then I think we could all agree that one was bullshitting us with a cliché draped in a disastrously silly argument from authority and move on from there. But to print it out and tape it to the back window of your car for all to see one’s apparent ignorance of the language, the historical and poltical consciousness, the punctuation of the very Founding Fathers to whose imprimatur one so desperately clings? To so apparently believe the thing so clearly wrong? —We need a different word, I think.

Horseshit?

But the relationship between the two is close, perhaps too close: most horseshit begins as bullshit, for instance, much as the example above—the words are the same; it’s the purveyors’ attitudes toward them that make the only difference. And what of those who deploy bullshit to defend a core notion of horseshit: does the reliance on what one ostensibly knows to be truthy call into question the degree of one’s actual ignorance of the truthiness of that which one’s defending? And think of the nightmarish, irresolvable arguments over Liberal Fascism: bullshit or horseshit?

Also, the bull and the horse don’t work so well in the metaphoric relationship. —Maybe it’s all bullshit, and it’s more that there’s those who shovel it, and those who don’t seem to notice they’re walking around covered in it?

(Gerald Ford, August 12, 1974: “A government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have.” Jefferson said, “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yeild [sic], and government to gain ground.” —Lost lashings of nuance aside, theories as to why Ford got transmogrified into Jefferson as the authority from which to argue tingle deliciously, don’t they?)

On a clear day you can see the ambiguous heterotopia.

“You’re supposed to have slightly less than one-fifth of your population in families producing children,” the man with the beard and rings said, “and at the same time, slightly over a fifth of your population is frozen on welfare…” Then he nodded and made a knowing sound with m’s that seemed so absurd Bron wondered, looking at the colored stones at his ears and knuckles, if he was mentally retarded.

“Well, first,” Sam said from down the table, “there’s very little overlap between those fifths—less than a percent. Second, because credit on basic food, basic shelter, and limited transport is automatic—if you don’t have labor credit, your tokens automatically and immediately put it on the state bill—we don’t support the huge, social service organizations of investigators, interviewers, office organizers, and administrators that are the main expense of your various welfare services here.” (Bron noted even Sam’s inexhaustible affability had developed a bright edge.) “Our very efficient system costs one-tenth per person to support as your cheapest, national, inefficient and totally inadequate system here. Our only costs for housing and feeding a person on welfare is the cost of the food and rent itself, which is kept track of against the state’s credit by the same computer system that keeps track of everyone else’s purchases against his or her own labor credit. In the Satellites, it actually costs minimally less to feed and ouse a person on welfare than it does to feed and house someone living at the same credit standard who’s working, because the bookkeeping is minimally less complicated. Here, with all the hidden charges, it costs from three to ten times more. Also, we have a far higher rotation of people on welfare than Luna has, or either of the sovereign worlds. Our welfare isn’t a social class who are born on it, live on it, and die on it, reproducing half the next welfare generation along the way. Practically everyone spends some time on it. And hardly anyone more than a few years. Our people on welfare live in the same co-ops as everyone else, not separate, economic ghettos. Practically nobody’s going to have children while they’re on it. The whole thing has such a different social value, weaves into the fabric of our society in such a different way, is essentially such a different process, you can’t really call it the same thing as you have here.”

“Oh, I can.” The man fingered a gemmed ear. “Once I spent a month on Galileo; and I was on it!” But he laughed, which seemed like an efficient enough way to halt a subject made unpleasant by the demands of that insistent, earthie ignorance.

—Samuel R. Delany, Trouble on Triton

Triton broke my brain more than any other book I ever read as a kid: I saw things differently after I read it—politics, sexuality, protagonists, sf. I read differently after I read it. And part of it was the thorny, prickly, problematic, nonexistent government of Triton and all the other Satellites, where you’re free to live under whatever system you want to vote for, or squat in the unlicensed free zones of whatever city you like—but behind it all that immutable, implacable, eminently sensible hand that invisibly takes what each might provide and in turn provides what each might need, but that also enables its agents to speak of “a” state and “a” system and to wage war on its behalf let’s not forget.

But it’s this idea of welfare, this road-not-taken over on the other side of the gulch from years of Reagan-Bush-Clinton, this road we might never have been able to take, but is nonetheless so dam’ sensible, where everyone’s given a hand up when they’re setting out regardless of etc. (and where everyone’s a stakeholder, and thus the system’s as untouchable as Social Security)—it’s this that came to mind when I read about a recent appearance on Glenn Beck’s medicine show by the Incredible paterfamilias himself, Craig T. Nelson, who in the course of a rant on how he’s sick of paying taxes for things that do not benefit him by God, said the following—

I’ve been on food stamps and welfare. Did anybody help me out? No!

It’s becoming clear that the question that will define the early 21st century is this: can the white man create a sense of entitled privilege so large even he can see it?

All signs point to no.

Cross-pollination.

I wanted to take a moment, just a moment, to share with you a couple of morsels from ![]() teaotter’s distillation of

teaotter’s distillation of ![]() ithurtsmybrain’s list of Pairings that Ate Fandom:

ithurtsmybrain’s list of Pairings that Ate Fandom:

From her “I’ll be in my bunk” list:

84. Nikola Tesla (The Prestige) / Sarah Connor (Terminator/SCC)

And you know? That works very, very well. It’s an intriguingly doomed disaster of a relationship in waiting, it is. But this next one, this:

From her “That would be (deliciously) wrong” list:

98. James Bond (James Bond films) / Bella Swan (Twilight)

I just. I mean. Words fail, you know? I mean.

Re: the new Whedon.

C+, for now, with some caveats. It’s not the gender stuff I’m on about; if you’re squicked, and you probably are, it’s in the mission statement, and remember he’s made yet another devil’s pact with the Maxim of network television, and if you can’t ultimately bring down the master’s house with the master’s tools you can at least wreak some interesting havoc before they come take them away. —I’m more keen to see what might be done with class: “normal” people on TV have always been (with some notable exceptions) what would be comfortably wealthy in the real world; the folks here have all the same material trappings of TV-normal, but they’re actually acting like the rich. So I want to see some mammalian certainties.

Other than that: everybody’s saying Topher’s the Xander of this one. Well, if by Xander you mean the young guy with the cynical wisecracks, I suppose, but that was never really what Xander was. Xander was the gut, as the Spouse likes to put it; the moral ground, the I-guy somewhat taken aback by all the paranormal goings-on, who calls bullshit despite the beam in his own eye, and is right more often than not; the mammal, as it were, which means Boyd Langton is the show’s Xander, thankyouverymuch.

No, Topher—the mad scientist, who lovingly details the backstories of the characters he creates every week for his Actives to play—Topher is the show’s Whedon.

But keeping that in mind will excuse only so much turgid dialogue. Up your game, people!