With thanks to Liz Wallace.

The crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women.

—Dan O’Bannon, Alien (née Starbeast)

FOOM! FOOM! FOOM! With explosions of escaping gas, the lids on the freezers pop open. —Slowly, groggily, six nude men sit up.

Having pretty women as the main characters was a real cliché of horror movies and I wanted to stay away from that. So I made up the character of Ripley, whom I didn’t know was going to be a woman at the time… I sent the people of the studios some notations and what I thought should happen and when we were about to make the movie the producer of the film jumped on it. He just liked the idea and told me we should make that Ripley character a woman. I thought that the captain would have been an old woman and the Ripley character a young man, that would have been interesting. But he said, “No, let’s make the hero a woman.”

—Dan O’Bannon, Cult People

[Veronica Cartwright] originally read for the role of Ripley, and was not informed that she had instead been cast as Lambert until she arrived in London for wardrobe. She disliked the character’s emotional weakness, but nevertheless accepted the role: “They convinced me that I was the audience’s fears; I was a reflection of what the audience is feeling.”

—Wikipedia, “Alien (film)#Casting”

FANTASTIC FILMS

Have you had any second thoughts about doing science fiction pictures in a row – first, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and now Alien?

CARTWRIGHT

Oh yeah. They were both screaming and running and crying films. But they were both very different.

FF

Are you worried being type-cast in the sort of role?

CARTWRIGHT

Well, I have to be very careful in picking my roles. I would like to do something comic next. I’m tired of crying. You know what I mean.

—Fantastic Films interview with Veronica Cartwright

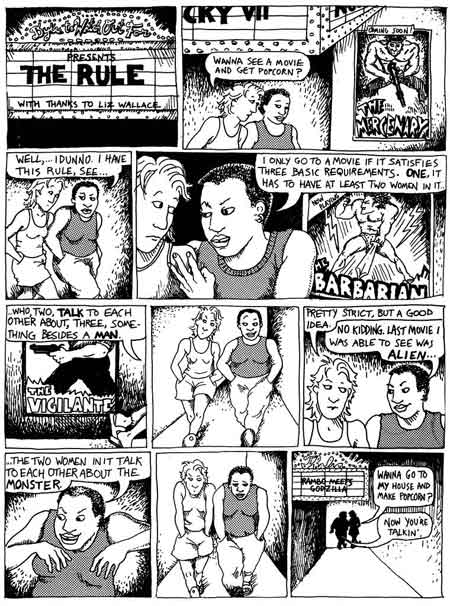

What’s the Mo Movie Measure, you ask? It’s an idea from Alison Bechdel’s brilliant comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For. The character “Mo” explains that she only watches movies in which:

- there are at least two named female characters, who

- talk to each other about

- something other than a man.

It’s appalling how few movies can pass the Mo Movie Measure.

Julie from Portland, OR, kindly emailed us to let us know that lefty blogs like Pandagon have been discussing the Mo Movie Measure a film-going concept that originated in an early DTWOF strip, circa 1985. We were excited to hear that someone still remembers this 20-year-old chestnut. But alas, the principle is misnamed. It appears in “The Rule,” a strip found on page 22 of the original DTWOF collection. Mo actually doesn’t appear in DTWOF until two years later. Her first strip can be found half-way through More DTWOF. Alison would also like to add that she can’t claim credit for the actual “rule.” She stole it from a friend, Liz Wallace, whose name is on the marquee in the comic strip.

—Cathy, not Alison, despite what the author tag says

By the way, when I coined the phrase “Mo Movie Measure,” I screwed up—the character in Dykes To Watch Out For who says it, isn’t Mo!

She bears a strong resemblance to Ginger, but it isn’t a definitive resemblance. The strip is from before DTWOF developed an ongoing cast of characters, so it is hard to tell if Bechdel intended Ginger to have been that character from that strip when Ginger started appeared in the strip. The character in “The Rule” seems physically bulkier than I recall Ginger being, but that could be a shift in drawing style.

Also, the bit about the two female characters having to have names—which I thought had been in the original comic strip—was apparently added by me. Oops again.

That’s how these cultural ideas develop—it’s just a giant game of “telephone.”

The Mo Movie Measure—what to call it now?

/bech•del test/ n.

- It has to have at least two women in it

- Who talk to each other

- About something besides a man

A variant of the test, in which the two women must additionally be named characters, is also called the Mo Movie Measure.

—Wikipedia, “Dykes to Watch Out For#Bechdel_test”

If any studio executives are reading this, let me give some examples: Names are things like “Annie Hall” and “Erin Brockovich” and “Scarlett O’Hara.” Things that are not names include, to cite some credits from this year’s movies, “Female Junkie,” “Mr. Anderson’s Secretary,” and “Topless Party Girl.”

The wonderful and tragic thing about the Bechdel Test is not, as you’ve doubtless already guessed, that so few Hollywood films manage to pass, but that the standard it creates is so pathetically minimal—the equivalent of those first 200 points we’re all told we got on the SATs just for filling out our names. Yet as the test has proved time and again, when it comes to the depiction of women in studio movies, no matter how low you set the bar, dozens of films will still trip over it and then insist with aggrieved self-righteousness that the bar never should have been there in the first place and that surely you’re not talking about quotas.

Well, yes, you big, dumb, expensive “based on a graphic novel” doofus of a major motion picture: I am talking about quotas. A quota of two whole women and one whole conversation that doesn’t include the line “I saw him first!”

—Mark Harris, “I Am Woman. Hear Me… Please!”

I was struck by the simplicity of this test and by its patent validity as a measure of gender bias. As I thought about it some more, it occurred to me how few of the classic works of literature that I teach to my high school freshmen would pass this test: The Odyssey? Nope. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass? Nope. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Nope. Romeo and Juliet. Nope.

What’s wrong with me?

—Frank Kovarik, “Navigating the waters of our biased culture”

Female characters are traditionally peripheral to male ones. That’s why we don’t want to hear them chatting about anything other than the male characters: because in making them peripheral, the writer has assured the women can’t possibly contribute to the story unless they’re telling us something about the men who drive the plot. That is the problem the test is highlighting. And that’s why shoehorning an awkward scene in which two named female characters discuss the price of tea in South Africa while the male characters are off saving the world will only hang a lantern on how powerfully you’ve sidelined your female characters for no reason other than sexism, conscious or otherwise.

—Jennifer Kessler, “The Bechdel Test: It’s not about passing”

Then and back again.

Now.

I put the book in the envelope. I put the mailing label on the envelope. I put the cash card in the self-serve machine and get the postage and put the postage on the envelope. I take the envelope and I, aw, hell.

—I mean this isn’t happening now. This is happening about five or six hours ago. (Twenty-seven or so as I edit.) (My first-pass edits, anyway.) —What I’m doing now is I’m typing. I mean I’m not typing now. Or maybe I am but not this. Right now what’s happening is you’re reading this. I have no idea how long from this now that now is, so I have no idea how long ago by now the now was when I did all that.

But: it had to be done. I’d made a promise. Deal’s a deal.

So I put the envelope in the mailbox and sent it back the way it came.

Then.

I took the book down off the shelf. Which one first, I’m not quite sure. —And I couldn’t tell you when it was I took it down. I’m pretty sure it was after I took War for the Oaks from the endcap display because mostly what I remember about the first time I saw War for the Oaks was the electric tingle sparking between fingertip and cover art as I reached for the damn thing; call it whatever the German portmanteau is for ohmygodwhatthefuckthislookscool. —Shock of the new, basically.  Which wouldn’t have been half as shocking had I already picked up Borderland and Bordertown, what with the elves and the motorcycles and the leather jackets and the rock ’n’ roll and all. —And while I remember the cover art for Borderland and Bordertown as a major factor in why I picked them up, I don’t remember that same spark; or not so potent, anyway. —But I could maybe have picked them up first. I was after all already a fan of the shared-world anthologies, Thieves’ World and Liavek and Wild Cards; here’s one more, with fæ punks; what’s not to love? —I think maybe I picked up Architect of Sleep after I picked up Borderland because Stephen R. Boyett, but I can’t be sure; I have a vague memory of being surprised that the one Borderland story (the postapocalyptic one, that feels like it’s in John M. Ford’s idea of the place instead of everybody else’s) was by the raccoon guy, but that’s a ghost of a wisp of a memory of a thought; untrustworthy. I could easily have picked up a book with a title like Architect of Sleep on a whim in those days.

Which wouldn’t have been half as shocking had I already picked up Borderland and Bordertown, what with the elves and the motorcycles and the leather jackets and the rock ’n’ roll and all. —And while I remember the cover art for Borderland and Bordertown as a major factor in why I picked them up, I don’t remember that same spark; or not so potent, anyway. —But I could maybe have picked them up first. I was after all already a fan of the shared-world anthologies, Thieves’ World and Liavek and Wild Cards; here’s one more, with fæ punks; what’s not to love? —I think maybe I picked up Architect of Sleep after I picked up Borderland because Stephen R. Boyett, but I can’t be sure; I have a vague memory of being surprised that the one Borderland story (the postapocalyptic one, that feels like it’s in John M. Ford’s idea of the place instead of everybody else’s) was by the raccoon guy, but that’s a ghost of a wisp of a memory of a thought; untrustworthy. I could easily have picked up a book with a title like Architect of Sleep on a whim in those days.  (Still would, actually. Wouldn’t you?) (Whatever became of the long-awaited sequel[s]?) (—Oh.)

(Still would, actually. Wouldn’t you?) (Whatever became of the long-awaited sequel[s]?) (—Oh.)

I don’t even remember if it was before I was in Brigadoon, or after. —What I can tell you is I’m sure I bought Borderland and Bordertown at the same time.

Pretty sure, anyway. —This was all a very long time ago, okay? How long? Let’s just say the shelf in question was in a B. Dalton’s and leave it at that.

Somewhat earlier.

Oh I was sunk already. I mean Tolkien, yes, and Lewis, and Heinlein and Asimov and Clarke, Alexander, Norton, Donaldson even, all of them hard on the heels of a diet of Matthew Looneys and Lewis Barnavelts and Bob Fultons and Furious Flycycles and Fat Bear Spies and Davids and Phœnices, but the thing that took off the top of my head was when Mom all unlooked-for brought home The Grey King. Magic that’s happening here, and now? —I mean, “here” was Wales, but it was a farm in Wales, and I lived on a farm, and oh who cares, I could make the jump for those songs, and that language like a secret code, and above all for the hint that something that big and that important could be just around a corner that I might see myself? Something made all the more real by how implacably and righteously unfair it was—

The rest of the books were secured post-haste. —I couldn’t sleep the night I turned twelve. I was waiting for the Old Ones, see. Maybe they’d missed me on my eleventh birthday. We’d been moving a lot.

Since then.

I was in Brigadoon, if I hadn’t been already. I graduated from high school. I saw Rocky Horror. I ran away from home the socially sanctioned way, to college; I dumped my high school sweetheart over the phone. I got an email address. (It was a much bigger deal, in those days.) I spent a summer in the Weaponshop of Isher, whose walls were held together with scotch tape; I got drunk, on beer, on wine, on White Russians. I tried acid, since I couldn’t stand smoking. I started drinking coffee in a diner in New York after seeing Crimes and Misdemeanors. I started smoking clove cigarettes. I dressed in nothing but black for weeks at a time and lost my heart beyond recall to my best friend’s sister. I saw Shock Treatment. I saw Liquid Sky. I saw Rare Air take the roof off Oberlin’s Finney Chapel. Twice. I found a Boiled in Lead album on CD. (It was harder to do, in those days.) I dropped out of college and got a job washing dishes so I could afford an 80-dollar-a-month walk-in closet that was so small I had to roll up my futon so I had room for my books. I found my heart again and sold the bass guitar I never learned how to play so I could cover rent. I was living with game designers, cartoonists, a proofreader, a botanist, a classicist, a computer archeologist. (I don’t think that’s what she ever called herself. But she made a killing, come Y2K.) Ten of us, in a five-bedroom house on a cul de sac? Somebody played me a Waterboys CD. I started dating a Jersey girl and when she moved in we swore we’d maintain separate bedrooms even as I was stashing my clothes in her dresser. Waiting for a plane in an airport in the middle of the country one of us turned to the other and said, we should get married, and the other one said, yeah, sure, only neither of us can remember which was which. We moved across the country on a whim, almost all ten of us. We got married, just the two of us, and then just the two of us got our own place. We bought a house. I backed into a career that had nothing to do with the writing I was starting to get done. We had a kid. We named her Taran, from the Lloyd Alexander books. We started buying more bookshelves for all the damn books.

I don’t know what happened to the Thieves’ World volumes. Whatever’s left might be in the attic of the house in Rock Hill? Along with that long-lost Dune Encyclopedia. The Wild Cards I’m pretty sure all got sold off. Liavek? A short while back I found another copy of the first one at Powell’s and I picked it up. The only Asimov in the house at this point is his Guide to Shakespeare which I really ought to give back to Dylan one of these days. The only Heinlein left is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. I should go get a copy of the White Hart tales; make a note of that. The original Coopers are long since lost, which is a damn shame; the old skool art direction kicked the ass of everything that’s come since; but I’ve got them on the shelves of course, along with Tolkien and Lewis and Alexander.

War for the Oaks? Bordertown? —Those books, the very ones I pulled off those B. Dalton’s shelves, tattered and worn, beat to hell, really—travel-stained, as it were—they’re up on the shelf above me as I write this. —Borderland ganged agley at some point in all that, but two out of three ain’t bad, right?

I should maybe see about replacing it.

A couple of weeks ago.

I was checking LiveJournal between Russian DDoS attacks (like you do) when I saw that ![]() janni had just posted the following:

janni had just posted the following:

If you’d like to borrow Welcome to Bordertown, and you’re willing to commit to both reading it in about a week and to them talking about it somewhere online, leave a comment below. I’ll mail you my copy, and then when you’re done, you’ll mail it back to me, and I’ll send it on to the next person on the list. (ETA: And will keep doing so until the book itself goes on sale at the end of May, however many people that turns out to be, and at that point see whether it’s still in good enough shape to keep sending around.)

And you know Stumptown was coming up and the Spouse was trying to get her presentation done and her covers drawn and her book off to the printer which doubles me up on toddler duty and I still had about 4,000 words to write as it turned out and only that upcoming week to do it and yet—I didn’t hesitate at all. “For this,” I said, “I could make the time.”

Three days later.

I got one of those big Priority Mail envelopes dropped on my desk. —Good lord, this one’s a biggun.

So the first thing I did—I’d like to say the first thing I did was read Janni Lee Simner’s story, because one should be gracious to gracious hosts,  but the first thing I did (after I stuck a bookmark in where Simner’s story began) was read “Fair Trade,” by Sara Ryan and Dylan Meconis, because good friends had made it to the Border, and because, y’know, comics, but mostly because I had to see the Dicebox poster hanging on the wall in the Dancing Ferret. And there it is, and there’s Farrel Din, and Alberta’s Last Thursday art-walk fits right in on Carmine Street; how weird, to find a bit of where I am now in a place I haven’t been back to in years. —And then it’s on to Janni’s piece, “Crossings,” which plays a mean little game with Team Edward, and Team Jacob, and the neatly deflatory resolution of Team Jacob is one of those things you can only do in a shared world like this: borrowing somebody else’s character whose hard set-up and expository work has already been done elsewhere in that somebody else’s story, so all you have to do is use ’em, make your point, and let ’em go back about their other elsewhere business. —So then it’s on to Will Shetterly’s story, “The Sages of Elsewhere,” because Wolfboy, because you have to check in with the folks you used to know back in the day, see what they’re up to, and he’s running a damn bookstore now. —Somebody’s getting older.

but the first thing I did (after I stuck a bookmark in where Simner’s story began) was read “Fair Trade,” by Sara Ryan and Dylan Meconis, because good friends had made it to the Border, and because, y’know, comics, but mostly because I had to see the Dicebox poster hanging on the wall in the Dancing Ferret. And there it is, and there’s Farrel Din, and Alberta’s Last Thursday art-walk fits right in on Carmine Street; how weird, to find a bit of where I am now in a place I haven’t been back to in years. —And then it’s on to Janni’s piece, “Crossings,” which plays a mean little game with Team Edward, and Team Jacob, and the neatly deflatory resolution of Team Jacob is one of those things you can only do in a shared world like this: borrowing somebody else’s character whose hard set-up and expository work has already been done elsewhere in that somebody else’s story, so all you have to do is use ’em, make your point, and let ’em go back about their other elsewhere business. —So then it’s on to Will Shetterly’s story, “The Sages of Elsewhere,” because Wolfboy, because you have to check in with the folks you used to know back in the day, see what they’re up to, and he’s running a damn bookstore now. —Somebody’s getting older.

And that’s another thing you only get with shared worlds, with proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fictions, and it’s a blessing and a curse: virtual world journalism: “I don’t know, it’s kind of like reading a newspaper. It’s not like the newspaper is inspiring, but you need to read it to see what happens.” —It’s hard sometimes to see the story qua story because you’re looking around in it, through it, past it for the bits and scraps of the larger, shared world beyond, and if something like Bordertown isn’t nearly so proprietary as the Marvel or DC multiverses, allowing individual stories the leeway they need to stand on their own merits, and voice, well—it isn’t nearly so persistent, neither: five collections of a few dozen stories, three novels, thirteen years between appearances: you’re hungrier, is the thing, for those scraps and bits.

So next it’s on to Emma Bull’s “Incunabulum,” because it’s not just characters and neighborhoods you want to catch up on, and damned if it doesn’t seem to me at least like she’s riffing a little Delany in the mix, with her declarative paragraphs, her blank Page inscribed by his wanderings about the city. —Then Nalo Hopkinson in “Ours is the Prettiest” goes and drops a whole new neighborhood (to me, at least): Little Tooth, and the Café Cubana, and Screaming Lord Neville, and the swirling madhouse stomp of the Jamboree suddenly never has not been a part of the Bordertown, even as she’s asking some pointed questions about whose magic exactly it is that gets reified by the world as it’s been in these books; and in “Shannon’s Law” Cory Doctorow brings the goddamn internet to the Border, or at least an internet, and the way it’s cobbled together foregrounds the sheer joy of the basic, simple idea which has nothing to do with computers when you get right down to it—though it’s a joy that’s tempered by the melancholy inherent in the story of a kid running away to live out the story of the hardscrabble internet pioneer, a story that’s long since dead and gone out here in the real. —And somewhere in and among all that I read the lyrics to Jane Yolen’s “Soulja Grrrl,” which gets performed in the background in “Crossings,” and the “Borderland Jump-Rope Rhyme” (and is it only me who thinks of Louis Untermeyer when confronted with folklorist L. Durocher? Probably) and also Neil Gaiman’s “Song of the Song” and Delia Sherman’s “The Wall” and Steven Brust’s “Run Back to the Border” (because Steven Brust) but my favorite of the songs I think has got to be Amal El-Mohtar’s “Stairs in her Hair,” which spawns or was spawned by a metaphor in Catherynne M. Valente’s bracingly chilly “Voice like a Hole”—

—which, that move right there, that’s not something particular to a shared-world book, like borrowing a character or a setting somebody else has set up; that’s just the way art gets made, you know, the usual game of inspiration and allusion and homage, only with something like a shared world, a collective enterprise like this, you get to see it happen a little more quickly, a little more clearly, you get that giddy sense of play and camaraderie that Holly Black talks about in her introduction, of a bunch of writers sitting around writing and reading and one-upping each other, that idealized circus that any bookish youth with half a hankering to write themselves would want to run away to join, to finally hear, like Jimmy Fix-It does, heading into Danceland with the rest of Widdershins in “Welcome to Bordertown,” by Terri Windling and Ellen Kushner, that you’re with the goddamn band—

Soon.

The book itself drops in exactly a month; 30 days from now (as I write this, yes), Tuesday, the 24th of May. —I was gonna tell you about the contests various contributors are running, to win their advanced reading copies of the book, in case you couldn’t wait, but I took too damn long and the ones that haven’t ended already are ending today. —Still: Emma Bull was asking for ways to get there, and Nalo Hopkinson is yet soliciting menus for a king-hell meal to be cooked once you make it; go and read the entries already posted, because damn. (Oh wait there’s hope; there’s always hope; new contests keep being announced—)

It’s grand, it’s giddy, it’s gloriously stupid, it’s too earnest by half like all the best things you remember from then, it was terribly important to a great many people and I’ve no doubt at all that it will be again. In the thirteen years it Brigadooned itself away the phantastick ate up the world in a way it never has before, and the n00bs have been dreaming of rings and swords and elves in technicolors we never had back then; and it’s so much easier now with the internets and all to tell each other how to get there and what to do when you’ve made it. —If you’ve been before, you can go back. If you’ve never gone, then what the heck are you waiting for? Go! Go!

Centenary.

Happy birthday, Reagan (curséd be thy name hock-phthooie!). —It’s easy to laugh, isn’t it? Hollowly, bitterly, bleakly, ha ha:

But now, seven years later, Reagan’s inquisitorial zealots are being decisively rebuffed in Congress, in the courts (even the “Reagan Court”) and in the court of public opinion. The American people may have been deluded enough to vote for him, but they are clearly unwilling to lay their freedoms at the President’s feet. They will not say goodbye to due process of law (not even in the name of a war on crime), or to civil rights (even if they fear and distrust blacks), or to freedom of expression (even if they don’t like pornography), or to the right of privacy and the freedom to make sexual choices (even if they disapprove of abortion and abhor homosexuals). Even Americans who consider themselves deeply religious have recoiled against a theocratic crusade that would force them to their knees. This resistance—even among Reagan supporters—to the Reagan “social agenda” testifies to the depth of ordinary people’s commitment to modernity and its deepest values. It shows, too, that people can be modernists even if they’ve never heard the word in their lives.

—Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts into Air,

Preface to the Penguin Edition (1988)

But! But. Oh, oh, but:

The great critic Lionel Trilling coined a phrase in 1968: “Modernism is in the streets.”

—ibidem, motherfuckers; ibid.

The whipsaw’s back, in full force: on a bad day, oh Lord, most days I’m laughing, ha ha. —On a good day, though? From up there, up on a steep hill, with the right kind of eyes? I can almost see the glimmer of the goddamn Shining Sea.

Cold clear water.

“It comes to me that I won’t be able to explain this well,” says Vincent. —He’s wrong, of course.

Stupidity.

A catastrophic storm dumps feet of snow from Texas to Maine and sure as death and taxes here they come, out of the woodwork:

And it isn’t the mistaking of weather for climate, or anecdote for data; it isn’t that for every city currently experiencing record lows, whole continents were hotter than ever before this past summer. It isn’t that such extremes, such monstrous storms, are precisely what’s predicted by the theory he so sneeringly believes is evidently bankrupt. And it’s certainly not the unkillable zombie nature of these soi-disant arguments, how every goddamn time it snows Republicans build igloos on the Capitol lawn.

It isn’t even that @PatriotD66 couldn’t manage to cut and paste a simple hyperlink. —No, it’s cold in the mesosphere, and a piece of rhodium was once a few hundred picokelvins away from absolute zero, so Al Gore is fat and probably an atheist. Fuck you, liberals.

It’s a neat little essay in power, this scene from Mulholland Drive: Adam Kesher, the hotshot director, walks into the meeting with his swagger and his golf club and his insults and his bluster and despite all these overt displays of power never has control of a goddamn thing.

It isn’t the menace in the soundtrack, that he can’t hear, or the cuts to Mr. Roque, whom he can’t see. It isn’t how Mr. Darby and Ray and Robert Smith, the bit players, recite their platitudinous nothings with a deliberately overrehearsed sheen, playing their roles to the hilt but no further, refusing the risk of actual agency in the struggle that’s played out around them. It isn’t even how the Castiglianes sit there and stare and refuse to engage beyond sliding the envelope across the table and trusting the others to do what it is they want, though that’s close; this is the girl. This is the girl.

It’s what Luigi Castigliane does with the espresso, of course.

It’s a shockingly ugly moment, what he does. The revulsion that crosses his face after the sip, and then how he doesn’t spit it out but opens his mouth and lets it dribble down his chin to puddle on clean white cloth, his tongue licking out reflexively, his hands trembling as he pats his chin clean with the unstained end of the napkin. It’s all very physical, very grotesque, a body out of control of itself, driven to do what it’s doing. It’s a sign of weakness, and thus an overwhelming show of power.

—Because it is a show, isn’t it? It’s why he orders the espresso. It’s why he insists on the napkin. It wouldn’t matter if it really were the best espresso in the world; he’d still let it fall from his mouth, too overwhelmed to manage to spit it out. This is the power I have, he’s saying. I can do this terrible shameful embarrassing thing and there is nothing, nothing at all that you can do to take advantage of it. That is how much power I have over you.

Strength—the bluster, the golfclub, the insults, the anger—strength is for the weak.

Which is why they won’t stop, the ilk of @PatriotD66. They’ll just keep making these unkillable arguments, so easily defeated, even as the ice caps melt. It’s why Bill O’Reilly won’t stop telling his parable of the tides; it’s why Megyn Kelly doesn’t care whether what she just said was laughably demonstrably false. It’s the secret meaning behind that much-vaunted Rove quote about the reality-based community: this is the power we have over you. We can say these terrible shameful embarrassing things, these appallingly stupid things, and there is not a goddamn thing in the world you can do to take advantage of it.

Testing elephants.

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it—

A solid essay from David Campbell on the prickly troubles baked into the term “disaster porn” (or “development porn” or “poverty porn” or “ruin porn” or “war porn” or “famine porn” or hell just plain “porn”) when used to refer to depictions or representations of atrocity and suffering:

[Carolyn] Dean calls “porn” a promiscuous term, and when we consider the wide range of conditions it attaches itself to, this pun is more than justified. As a signifier of responses to bodily suffering, “pornography” has come to mean the violation of dignity, cultural degradation, taking things out of context, exploitation, objectification, putting misery and horror on display, the encouragement of voyeurism, the construction of desire, unacceptable sexuality, moral and political perversion, and a fair number more.

Furthermore, this litany of possible conditions named by “pornography” is replete with contradictory relations between the elements. Excesses mark some of the conditions while others involve shortages. Critics, Dean argues, are also confused about whether “pornography” is the cause or effect of these conditions.

The upshot is that a term with a complex history, a licentious character and an uncertain mode of operation fails to offer an argument or a framework for understanding the work images do. It is at one and the same time too broad and too empty, applied to so much yet explaining so little. As a result, Dean concludes that “pornography”

functions primarily as an aesthetic or moral judgement that precludes an investigation of traumatic response and arguably diverts us from the more explicitly posed question: how to forge a critical use of empathy? (emphasis added)

That’s the trouble with “porn” as a critical term: it’s been pwned by the pejorative.

For some reason the same day I got pointed at Campbell’s piece I thought of “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” for the first time in years.

Bruce Cockburn wrote the song in 1984, shaken by a visit to a Guatemalan refugee camp; apparently, it was his first explicitly political single. —A helicopter flies overhead, everyone scatters, and he wishes he had a rocket launcher: “I’d make somebody pay,” he sings, and then “I would retaliate,” and then, “I would not hesitate,” and finally, “Some sonofabitch would die.”

Canadian radio apparently used to fade out just before that last line.

Anyway, I’d never seen the video before:

And while I’d never call it pornography, and I don’t for a moment think it in any way creates an incurable distance between subject and viewer or leads to compassion fatigue nor do I see it at all as a threat to empathy or as something to dull our moral senses nonetheless: there is something unpleasant going on in that video and what it’s doing, what it did.

Disaster tourism, maybe? Atrocity holiday? —Oh to his credit Cockburn himself insists the song is “not a call to arms. This is, this is a cry…” And the video does indeed highlight—well. His impotence? His frustration? His embarrassment? As it keeps cutting back to him, singing with a vaguely pained expression in those theatrically smoking ruins. Goddamn I wish I could do something. Man if I had a rocket launcher. What fury I would wreak to help you all. Would that I could.

And I just keep thinking of what it was the Editors said: oh but you paid your taxes. Would that you had not. —Oh but Mr. Cockburn’s a Canadian. And that’s an American-made helicopter in that opening lyric, isn’t it.

If I had to functionally describe pornography, this elephant in the rhetoric? —Well. I’d always thought I’d copped it from Kim Stanley Robinson, but damned if I can find the passage in Gold Coast where I thought he’d laid it out. But: any work that stimulates an appetite without directly satisfying it, that tacitly but openly acknowledges that’s just what it has set out to do, that fulfills an agreement between artist and audience to appeal to this metaneed, to satisfy the need to need to be satisfied. And there’s achingly gorgeous effects to be wrought with this stuff and sublimities galore, and dizzying pushme-pullyou games of surrogacies and vicarosities to be played, and squinting at the elephant this way lets us get at some of them while dodging the worst of the pejorations: we can speak of food porn, and designer porn, and book porn, and furniture porn, and we all know what it means; we’ve seen it. —Catalogs and lifestyle magazines: some of the most pornographic work we make.

In that sense? Then maybe? This commercial for a pop song skirts that border of the pornographic: a thirst for justice, an appetite for outrage stoked but explicitly, openly left unsated. —Oh but then we see the problem’s not the numbing, not at all: it’s the transference, the metaneed, the outrage pellet, the thing called up and bodied forth only to satisfy something else entirely, something inevitably smaller. The pornography of politics, the smut of Twitter revolutions, the whoredoms of Facebook petitions—

Good Lord. The trouble with the elephant isn’t that it’s hard to describe. It’s that when it gets up a head of steam it tramples everything in its path.

Cockburn, who has made 30 albums and has had countless hits, visited another war zone this week: Afghanistan. And the conflict involves a member of his own family. His brother, Capt. John Cockburn, is a doctor serving with the Canadian Forces at Kandahar Airfield.

[…]

Cockburn drew wild applause when he sang “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” which prompted the commander of Task Force Kandahar, Gen. Jonathan Vance, to temporarily present him with a rocket launcher.

“I was kind of hoping he would let me keep it. Can you see Canada Customs? I don’t think so,” Cockburn said, laughing.

The vision thing.

So what we have here, this is the discussion forum for Shadow Unit, which is maybe the largest webfiction serial currently available for free out there? I dunno. Certainly has some of the biggest names attached to it, folks like Emma Bull and Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette and suchlike. Whichever. —There’s this thread, then, been up for a bit, looking for “second favorite” webfiction joints: fanfic or OG, novels or linked short stories or whatever, but fiction. Prose. Words on a screen. You know? —But after about three responses (including the city, yes, thanks muchly) somebody posts a list of webcomics they like to read, since they don’t really read any other online written word fiction, and that’s it: the rest of the discussion, with one or two exceptions, on this thread devoted to promoting webfiction, merrily and enthusiastically tosses links to webcomics back and forth and back again. (Including the box, yes. Thanks also.) —I mean, there’s reasons, sure. Of course there are. (There always are.) But still. You know?

In Soviet criticism, terms come to you!

Catherynne Valente went on a mild tear about “speculative fiction” which itself went and garnered just about a hundred comments in the first hour of its existence. Apparently, people like jawing over jargon! Who knew?

What’s interesting, about the rant and its responses, is how subtly different everyone’s idea of speculative fiction is. Which, granted, is true of almost all genera, by definition (if people remembered the same they would not be different people; think and dream are the same in French). —Valente (and some, if not most) sees it as a failed attempt at a big tent, a fantastika whose clinical air of technical specificity (these fictions, and their speculations) renders it incapable of embracing the messy, ugly, gloriously squishy numinosity of fantasy as she is wrote. —Others, including, well, me, see it as—and maybe it’s the folk etymology I’ve concocted in my own head? See, when the New Wave came along, people started casting about for something to call the stuff that was inarguably in the same basic arena as science fiction but wasn’t, how you say, strictly scientific, was insufficiently hard, and so some folks started to call it sci-fi as a way of making the allegiance clear while downplaying the whole science aspect of it, but then Harlan Ellison threatened to punch them, so they had to call it something else instead, and they settled on speculative fiction. Which is fine enough at what it does, but what it does is kinda wishy-washy, has no convictions to lend it courage, and lets people like Margaret Atwood reify their own takes on McCarty’s Error (“To label The Sparrow science fiction,” he said in his age-old review, “is an injustice and downright wrong”) with their hairsplitting games of science fiction and speculative fiction: it’s the travesty of porn and erotica all over again. —Any genre distinctions that hinge on de gustibus questions of “quality” are worse than useless.

Anyway, there’s a lot of people unhappy with “speculative fiction” as a term, almost as many as are unhappy with “graphic novel” (and luckily speculative fiction even after all these years isn’t nearly so firmly rooted as that other ugly compound). But there’s still the question of what to call the stuff that’s obviously “science fiction” but that isn’t strictly speaking sciencey; how do those of us who do not wish to be punched by Harlan Ellison meaningfully name and situate something like Star Trek without drowning in eye-rolling trolls who simply cannot resist pointing out how wrong it is to have sound in space? —Well, you wear the original term down further: from scientifiction to science fiction to sci-fi to SF, which (sigh) is an acronym, and leads to ugly coinages like “SFnal,” but has the signal advantages of: being immediately recognizable; not insisting on science; not being “speculative fiction.”

So I mentioned as much, over on the Twitter, my preference for SF, and @catvalente immediately pointed out the silent F therein. —Which brought me up short; I’d never thought of speculative fiction as kitchen-sinking fantasy qua the phantastick: fables and myths and the very best magic aren’t speculations, they’re demands; not games of WHAT IF, but DAMN WELL IS. So I see no problem replacing speculative fiction with SF; they do roughly the same job for me; that silent F wasn’t silent but always ever elsewhere. —Yet of course there are going to be those who do try to make the term as inclusive as it pretends to want to be on the tin, and will be caught up short by its shortcomings. And so.

(Once more, I’m driven to mock an old XKCD strip:

(Hard sciences? Ha! Working with objectively measurable quanta is easy.)

—Where was I? Oh. Musing that maybe I shouldn’t be quite so sloppy with terminology when throwing these words about. —Not that I’m likely to get less sloppy, but I should at least point to the pier’s mission statement (or mission essay, we don’t really go in for pith in this sort of thing) in this regard, “Ludafisk”: critical definitions of such things as genres can never be necessary or sufficient; are, like tools, highly situational; therefore, like tools, are to be put down and taken up again as needed. I could, I suppose, be a little more clear when I’m switching from flat-head to Phillips, say. Try to be, anyway.

(I keep kicking around a classification or hierarchy of terms, of modes, say, for SF and fantasy and horror considered as part of the triskelion; of idioms, referring to SF furniture or fantasy furniture, working with ray-guns-and-rocket-ships or rings-and-swords-and-cloaks, of genres being those contractual obligations such as steampunk or urban fantasy. But I keep resisting. So pretend I said nothing.)

—I would be remiss to those of you who follow along via RSS if I didn’t point out that in earlier entries in this occasional series old friend of the pier Charles S has been doing a yeoman’s job of chiding and chivvying and generally teasing the most interesting bits out for further consideration. So.

See, when you assume—

I wonder how much of the blame for things as they are (for many and varied values of things) might not be laid at the nigh-ubiquitous feet of the first-person smartass.

Vive la différence.

Trouble with Ted Chiang’s seemingly pat differentiation is most stories by construction must take their protagonists personally, and see them as special snowflakes: they are, after all, the people whose story is being told, without whom the very universe would not exist. (Think a moment how so much SF ends up as fantasies of political agency. There’s the storyable, world-shaking stuff!) —I like Jo Walton’s better: fantasy’s the stuff we know, in our bones, very much because it isn’t real; SF is that much harder because every jot and tittle you set down must always be checked, and checked again: like anything else that’s solid, science never stops melting into air…

It’s all her fault!

Via a one-off link over at Alas, an update to pronoun-sexing: apparently, Anne Fisher’s the one who first advocated “he” as the gender-neutral pronoun for English, upset as she was over numeric inconsistencies with then-popular “they.” —Or, well, maybe not.

Few, and carefully considered, and he broadcasts them like a beacon in every weather.

Martin Seay (of the Ke$ha essay linked above for the next little while) has written other things, of course; of course he has: he has a blog! —Today I read this longer piece on Norman Rockwell (and Spielberg, and Lucas, and a whole host of somethings else), and if you have a few minutes cleared at some point or other in the next little while, I urge you to do likewise.

You can add up the parts;

you won’t have the sum.

So you can anyway imagine the grin on my face when I tripped over Mendlesohn’s Corollary to Clarke’s Third Law:

Any sufficiently immersive fantasy is indistinguishable from science fiction.

Problem being she’s talking about immersive fantasy, and she classes or tends to class urban fantasy, the thing we’re pointing to, as intrusion.

—I’m gonna have to get into this, aren’t I.

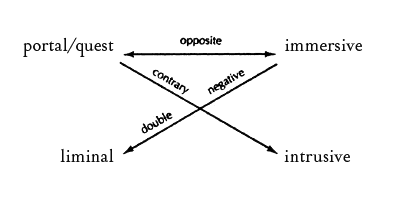

Farah Mendlesohn sat down to grapple with the rhetorics of fantasy; she stood up with a taxonomy for organizing all of fantastic fiction, every last drop of it, based on the narrative strategies, the rhetorics used to establish the relationship between the normal, the disputable here of us, and the numinous, the ineluctable there beyond the fields we know—a sound basis for a system of describing (and not prescribing) fantasy as she is wrote, you’ll agree. (—What else is there?) —Her taxonomy, then, proposes four means whereby this relationship is inscribed, interrogated, upended and maintained:

- the portal/quest, in which we go from here to there;

- the immersive, in which there is no here but there;

- the intrusive, in which there comes here and must return;

- the liminal, in which there was here all along.

So. Four. (With yes an implied fifth, and an obvious sixth. —But for now, four.) —Why only four? Why these four? —Well.

A while back I found myself idly toying with ways to structure and organize sexual imagery, energy, symbols and roles, flows of power and expectation, something a step or two beyond the brutally stupid dichotomy we’re mostly stuck with, the masculine, the feminine, which all too often boils down to the merely phallic. —Why, even Freud, who thought long and hard about this sort of thing, once said,

if we were able to give a more definite connotation to the concepts of “masculine” and “feminine,” it would even be possible to maintain that libido is invariably and necessarily of a masculine nature, whether it occurs in men or in women and irrespectively of whether its object is a man or a woman.

And not all the handwaving footnotes in the world can keep me, even here in the comfortable lap of 21st century cisgendered heteronormative privilege, from calling that out as the most specious of bullshit, a definition desperately trying to maintain the worldview in which it’s relevant. —Nonetheless, he did, and it did, and look where it’s all gotten us: bros before hos, amirite?

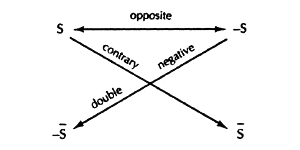

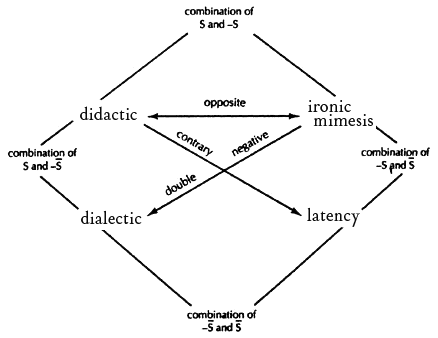

Anyway. At about the same time I was re-reading Red Mars, and so once again got caught in the seductive grip of the Greimas semantic square:

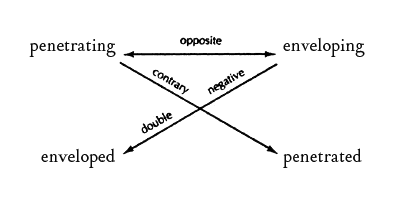

Proposition S; the opposite of S; the negation of S; the negation of the opposite of S. No simple dichotomy, this! (And it’s just the first stage.) —What I ended up with, then, looked something like:

I tried to go with terms at once as suggestive and yet sex- (and gender-) inspecific as possible—wait, you’re saying, the four, what on earth does all this—with the penetrating, and the enveloping, I mean, any of us, male, female, straight or gay or polymorphously whichever, cis or trans or not at all partaking, any of us—fantasy, you’re saying, urban fantasy, what does this have to do with—we can all identify with penetrating, or enveloping (I almost went with swallowing, but that’s a bit too too, you know?), with being enveloped, with being penetrated; we can all see them as valid stances, as desires, as starting points each as proper as the other, right? —Seriously, you’re saying, what does this have to do with the urban fantasy as sf and that taxonomy you were, and I’m saying patience, watch, count it off, do the math, look at them over there, they figured it out—

It’s a trifle, is what it is, a toy. I mean, I trust it demonstrates how easily the brutally stupid dichotomy can be disrupted, but Christ, anyone who thinks about it half a moment can see that. —And yet it keeps coming back, doesn’t it? Men do this. Women want that. Way of the fucking world. —I mean look where little ol’ cisgendered mostly heteronormative masculine me put the penetrative end of things, huh? Proposition S. Look how everything else gets othered by that placement, with all the opposing and the negating. —“The power involved in desire is so great,” says Delany, responding to (among other things) that Freud quote above,

that when caught in an actual rhetorical manifestation of desire—a particular sex act, say—it is sometimes all but impossible to untangle the complex webs of power that shoot through it from various directions, the power relations that are the act and that constitute it.

Sex and sexuality, desire and power, it’s all too terribly complicated for simple logical constructs to contain. The models are all wrong and useless. You start to feel like Two-Face in the Grant Morrison – Dave McKean Arkham Asylum, weaned by well-meaning psychotherapists from the binary limitations of his ghastly decisive coin to the six-fold options of a die, multiplying the ramifications of every choice he makes up to the paralyzing forest of possibilities in a decision-making system based on the fall of a pack of Tarot cards—he pisses himself, unable to decide which way to turn. No wonder the brutally stupid dichotomy keeps coming back! It’s wrong, but at least it gets things done!

But: if we replace the sex with rhetoric—

Two sides, normal and numinous, here and there; the membrane between them (for how else could we tell the two sides apart, or that there were two at all? —Remember: the rhetorics each in their own way inscribe and maintain the relationship between the two, which depends upon that difference); the crack within the membrane (for how else could the light get in? how else would it all be storyable?)—just adjust which is where as you go and oh do let’s be blunt about it: we (along with the protagonist) set out from the normal through a portal on a quest to penetrate the numinous; we (along with the protagonist) are utterly immersed in the numinous as it envelops us; we (along with the protagonist) are intruded upon by the numinous as it penetrates our normal world; we (along with the protagonist) find the numinous enveloped within us, a tremulous limen within our grasp. —Take the portal/quest, the ur-fantasy for most of us, and set it in the role of proposition S; the rest, oppositions and negations, fall neatly into place.

Now one of the reasons I like arranging Mendlesohn’s taxonomy this way is it helps to visualize the pitiless logic of here and there that underlies it all (oh, but be careful! Such logic is seductive, and narcissistic: in love with itself it ignores anything that isn’t, and always risks turning brutal and stupid. There is an implied fifth, of course: everything else. And also the obvious sixth: none at all. But for now let’s stay in the square). But also: there’s the rhetorics primarily associated with each type:

- the portal/quest, as previously discussed, depends upon the didactic to tell the world as it is to its protagonist, and us;

- the immersive plays with ironic mimesis, its po-faced protagonist taking for granted things we’d find most extraordinary;

- the intrusive pushes and pulls its protagonist (and us), depending on latency (for irruptions must always prove short sharp shocks);

- the liminal eschews its protagonist and reaches up to us direct, through the dialectic between the reader and the work.

Take these, hang them about the square, and lift it all up to the next stage (I did warn you that the square was but the first move we could make):

And we start to see some of the moves hinted at in the taxonomy, the ways the sets can fuzz, and not: that the didactic of the portal/quest can shade to ironic mimesis, as its protagonist learns the ways of the world, and can reach even for an archly knowing dialectic with the reader, but can’t except in the very opening pages do much with latency—there is a door and we will go through it in this scheme of things. Why wait? —That the ironic mimesis of the immersive can always go didactic to drop some (forgive the term) science on us, or play with the latency of the wonders it cannot admit it delivers, but can never reach for that dialectic which breaks the seals between its there and our here, threatening the illusion of immersion. —That the latency of intrusion can use both ironic mimesis and a knowing dialectic in its arsenal of pushes and pulls, but can never come right out and and say what’s happening, flatly, and expect to pull it off. —That the liminal can use—must use—both latency and the didactic to keep us at once engaged and at bay, but would (ironically) find ironic mimesis too open and direct an admission of the wonders it’s always on the edge of revealing.

As, I mean, a for instance. Don’t take my word for it. I’m just fucking around at this point. —Christ, I haven’t even gotten into how this all does and doesn’t work with the Cluthian triskelion. —Mostly what I need for you to understand before we take our next step is this: that Mendlesohn sees the immersive school as having the most in common with the “closed” worlds of SF, which is what her corollary means, and why my grin’s provisional at best; that she classes urban fantasy as intrusion, as stories of push-me–pull-you latency, and thus not SF at all, at least not in that sense.

But—

As Mendlesohn herself notes (citing among other works Perdido Street Station,) an immersive fantasy can host an intrusion.

I’d argue in turn that an intrusion not successfully beaten back must then become an immersion.

Thus as to how it is that urban fantasy must necessarily be SF, you see—

This still isn’t about steampunk, dammit.

But via Jess Nevins I learn of Beyond Victoriana, dedicated to “multicultural steampunk and retro-futurism—that is, steampunk outside of a Western-dominant, Eurocentric framework.” —Updates every Sunday and Wednesday.

Anent the preceding:

I feel a bit sheepish over how I left the problem of steampunk, for all that this isn’t about steampunk, and won’t be, dammit; a bit glib, to toss off Íkaroi and asymptotes without acknowledging how any one of us worth our salt should take a fence planted and a gauntlet thrown like that: back up for a goddamn running start. —And I never should have linked to Catherynne Valente’s magisterial rant without acknowledging her morning after.

Still, do or do not; there is no try. Tripping over the gauntlet and faceplanting into the fence does nothing but bloody your nose and besides, the fence likes it. —And anyway I’ve got angels of my own to wrestle with. (The themes of seduction and colonization running just under the surface of urban fantasy, say.)

But:

(And I don’t yet know for sure quite what to do with this which is why it’s being stuck over here to one side as a parenthetical—)

There’s this thing Nisi Shawl didn’t say so much as allude to and play with, on a panel at the 2009 World Fantasy Convention:

What I said was that some critics had called cyberpunk a reactionary response to feminist science fiction. This is true. Specifically, I’m pretty sure this is something Jeanne Gomoll, among others, theorized about.

I brought up this point because though I don’t personally believe that cyberpunk was a reactionary response to feminist science fiction a) It’s an interesting premise to examine; b) Examination leads me to think that while cyberpunk and the cyberpunks were not antagonistic to feminist science fiction, part of the media hype surrounding it was an attempt to find something, anything to look at other than feminist science fiction; and c) Parallels can be drawn between the popularity/commodification of cyberpunk and the popularity/commodification of steampunk in relationship to, respectively, feminist science fiction and speculative fiction by POC. Also, I was being somewhat provocative, which I think is kind of my job on a panel: to entertain as well as educate.

This isn’t about steampunk, dammit; I’m not trying to kick it once again. (Here, have some lovely steamy boosterism from Nisi Shawl, a glorious backing-up for a good hard run at the damn thing.) —It is an interesting premise to examine—note the elision to genre-as-marketing-category in the above, which is where marketing dollars pool, instead of fears; but remember that marketing dollars have fears of their own.

But this is about urban fantasy, and while I know for a goddamn fact the way only someone who’s lived through the past forty years can know that history doesn’t progress, not any more than evolution does, that any narrative here is necessarily constructed by a guiding, editing, distorting hand without which you have just a bunch of stuff that happened, and while I’d never presume to call urban fantasy qua urban fantasy in any way a feminist genre—it is more concerned, much more fundamentally concerned with gender and interpersonal relationships than cyberpunk ever was, and while I’d never make the assertion that the leather pants and the elves in sunglasses and the vampire CEOs and etc. and etc. are in any direct or meaningful way an offshoot of or outgrowth from or improvement on cyberpunk—don’t get distracted by the dam’ furniture—

Still. The idea won’t leave me alone, is all I’m saying.

But anyway the urban fantasy crew for whatever bucks it might bring in is still I gather second class in the Beowulf game; fangfuckers, they’re called, and paranormal romance is said too often with a sneer; I know, I’ve felt it on my own lip more than once. —It’s late. I’m digressing. There’s other moves to make. I need some sleep.

Obversity.

There’s every now and then the occasional moment you can look back at, point to, a specific slice of spacetime where you can say there, that’s where the science dropped. —A while ago Felicia Day went and said this about a book by M.K. Hobson, friend of the pier:

And when I saw that I said to myself now waitaminute what on earth is she doing calling out a steampunk novel to urban fantasy fans? Because I mean on the one hand, goths who just discovered brown. On the other, leather trousers half-undone. But there came a tapping on my shoulder and a light was glaring in the corners of my eyes and when I turned to look I was struck dumb at that very instant by the insight:

Steampunk is the fantasy to urban fantasy’s SF.

You remember what I told you about how we were gonna abstract it up and out? How you shouldn’t get distracted by the furniture of swords and rings and rocketships, or zeppelins and tramp stamps? —Yeah. Like that.

In this book I argue that there are essentially four categories within the fantastic: the portal-quest, the immersive, the intrusive, and the liminal. These categories are determined by the means by which the fantastic enters the narrated world. In the portal-quest we are invited through into the fantastic; in the intrusion fantasy, the fantastic enters the fictional world; in the liminal fantasy, the magic hovers in the corner of our eye; while in the immersive fantasy we are allowed no escape. Each category has as profound an influence on the rhetorical structures of the fantastic as does its taproot text or genre. Each category is a mode susceptible to the quadripartite template or grammar—wrongness, thinning, recognition, and healing/return—that John Clute suggests in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy (338-339).4

—Farah Mendlesohn, Rhetorics of Fantasy

4. Clute and I have had a number of discussions over which formulation of the grammar of Full Fantasy to use here. Clute being Clute, the formulation has gone through several revisions, rethinkings, and renamings. In the end, and knowing this is not his preference, I have chosen to go for the most physically accessible formula; that is, the version in the Encyclopedia.

So I was working my way through Mendlesohn—remember Medlesohn? This all started as a sequence of posts about Mendlesohn—and hit that passage right there in the introduction and had to stop. A grammar? Of fantasy? Qua fantasy? What on earth was this thing, with its talk of stages, categories, wrongness and thinning, recognition and return? I didn’t (and don’t) have a copy of the Encyclopedia myself; Clute I knew only vaguely as a critic (and spoiler) of some renown; Mendlesohn doesn’t spell it out much beyond the above, and some tantalizing hints throughout the chapters on her own quartered circle—but she did pick the most physically accessible of the possible formulæ, right?

Well, at $150 a pop, not so much. —And yes the library has a reference copy, but easy trumps free every time: a Google or three, and there we were: a talk given in 2007, making this if not the vision or thinking or naming close to that which Clute might rather Mendlesohn have used, at least a candidate rather close in time to the composition of the above.

Go on then, read it. —Even though I’ll be summarizing (in my own idiom and for my own purposes), you’ll want it under your belt so you can see for yourself where my model of her model of his model gangs agley.

Just—remember, okay? All models are wrong—but some are useful.

Clute’s model—at least as presented in this talk—isn’t just a quadripartite template for fantasy, but a triskelion encompassing, well, everything: the fantastika, which is another way of saying /fantasy/ or «fantasy» (or «smoke», or /mirrors/): “that wide range of fictional works whose contents are understood to be fantastic.” —This fantastika is posited as a Dionysian return of that which had been repressed by the cool, composed Appollonian excesses of the Enlightenment; by 1700, Clute notes, (at least within English literature),

a fault line was drawn between mimetic work, which accorded with the rational Enlightenment values then beginning to dominate, and the great cauldron of irrational myth and story, which we now claimed to have outgrown, and which was now primarily suitable for children (the concept of childhood having been invented around this time as a disposal unit to dump abandoned versions of human nature into).

This stuff, this fantastika, “the irrational, the impossible, the nightmare, the inevitable, the haunted, the storyable, the magic walking stick, the curse,” (the rocket, the ring, the sword, the goggles, the guitar) are then pressed into service as a means of dealing with those world-changes wrought by the aforementioned Enlightenment, the geist haunting the Zeit, the “World Storm” in the title of his talk: the unchanging state of constant change brought on by the onrushing Industrial Revolution, the Singularity that has always already been happening for some time now. —Clute identifies three main modes of this fantastika as of the twenty-first century, and bemoans their names: Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror—modes, mind, not genera, not idioms, not category fictions, not rigorously defined academic exercises, but modes, each passing through or touching on four basic stages of story, each differentiable by the skew it brings to those stages, the way they roll through the fingers and trip from the tongue:

- Fantasy, as noted, begins in wrongness, proceeds through thinning, has a moment of recognition, and then returns by turning away from the world storm;

- Science Fiction begins with the novum, the new thing, proceeds through cognitive estrangement on its way to a conceptual breakthrough, and ends up in some topia somewhere, in the eye of the storm perhaps, or somewhere through it, past it, beyond;

- and Horror, which begins with a sighting, then thickens about our protagonists until it can revel in the moment when we cannot look away, and leaves us shivering in its aftermath.

Or, if I might boil it all down to a grotesquely simplified reduction: a rejection, a celebration, a surrender.

Are there problems with this model? Oh yes. How could there not be? Setting aside for a moment how easily and even treacherously the one mode can slip to another within the same story, passage, sentence, you start squinting too closely at the details; who among us has not celebrated their surrender to something rejected? (We are Legion; we contain multitudes.) —No, I’m looking at the kernel of it all, the bedrock assumed beneath our collective feet:

—given the obvious fact that only bad worlds are storyable—

And oh, but this is Crisis-continuity, this is someone always insisting the stakes must be higher, this is someone just stopping in the face of the problem of Utopia, this is why movies suck and television doesn’t and the difference between Marvel and DC and this is much too much to go into right now but most of all it’s wrong, I mean let them be mindful of death and disinclined to long journeys, yes, but for fuck’s sake they will still be storyable, will still have stories, stories I at least want to hear and see and read—

Oh but that’s a tangent. Excuse me a moment. Ahem and all that. —What I meant to say was problems aside the simple clarity that triskelion brings to any discussion of the phantastick (to use my own preferred bumbershoot) is a powerful explanatory tool: one can easily see now why Star Wars is fantasy, and Star Trek is science fiction, and how delightful it is to consider Last Night as a gentle, whimsical, Canadian horror film.

And steampunk, well: but here’s another place the model starts to break. —Oh it’s fantasy, all right, whether there’s zombies or not; it is a nigh-desperate attempt to return, to reject, to recognize, but look at what’s being recognized, look where we’re returning: we don’t want the world-storm not to have happened. We want to go back to when it all began and try to do it over again. To ride it out better this time. To restart that Singularity, to make sure we get the zeppelins, dammit, and the goggles, and all the adventurous history this thinned mean world of ours won’t let us have. —Steampunk wants a mulligan on the Industrial Revolution, because what if? What if we had?

(—But that also requires a mulligan on imperialism. Oh what if. What if we hadn’t.)

So it isn’t as simple as all that, this celebration of something rejected, this adamant attempt once again to duck some awful, ugly truths. Still I think the triskelion helps us catch a glimpse of why it is the Great Steampunk Novel’s an asymptote no Icarus has yet managed to brush.

As for why urban fantasy’s really SF, well—

QFMFT

“It’s a bit of a wonder to me that there are so many people who remain a-quiver with anger over the fading heyday of crit-theory jargon in the humanities when there are fields of professional training as chock-a-block with buzzwords as ‘strategic management’ appears to be.” —Timothy Burke