In Memison, one must try the fish.

An exquisite little jewel of a review from M. John Harrison of a book that doesn’t exist so much in the particular, but very much in the aggregate; he comes at recent preoccupations hereabouts from other angles very much appreciated.

I mean the matter that you read, my lord.

Matter matter matter, let’s see—we’ve moved, across town, from Ladd’s Addition to Rose City; we’re homeowners now, and again, which means we can paint the rooms the colors we’d like, but also means we have to strip and sand and sweep and repair and replace and prime and tape and paint and paint again, over and over for each different color, and, well. Time passes. You look up and wonder what you’ve accomplished and then you look around, and yes, but also yes, well...

As for words words words: as to written, and here you must imagine me sucking my teeth. I’ve got the fortieth novelette queued up and ready to go starting Monday, but that’s the only one I’ve written this year, and last year I managed to write most of five, and the discrepancy gnaws. I’d point to the work alluded to in the paragraph above, and the work associated with the day job (turns out, preparing for and supporting a federal criminal trial? Time-consuming), but work we will always have with us, and the work still needs to get done, and the forty-first isn’t at the moment coming any faster, and as for anything written around here, well...

But as to have read, have been reading, to be read: currently bouncing between two big books, each expansively large in their own particular idioms: on the one hand, I’ve decided instead of dipping in almost at random to sample this run of stanzas, or that, to work my way through the F--rie Queene from first line to last, drawing what dry amusement I might from the coincidence in age between myself when I finally started it (53) and Virginia Woolf, when she finally started it (53)—

The first essential is, of course, not to read The F--ry Queen. Put it off as long as possible. Grind out politics; absorb science; wallow in fiction; walk about London; observe the crowds; calculate the loss of life and limb; rub shoulders with the poor in markets; buy and sell; fix the mind firmly on the financial columns of the newspapers, weather; on the crops; on the fashions. At the mere mention of chivalry shiver and snigger; detest allegory; and then, when the whole being is red and brittle as sandstone in the sun, make a dash for The F--ry Queen and give yourself up to it.

—only to find myself at the end of the first 12 cantos looking up, blinking, as our avatar of Holinesse, that Redcrosse knight his own dam’ self, so happy in his ever-after with Una, his one true only, the only one true only, suddenly just ups and leaves her in the space of eight lines of iambic pentameter and a single alexandrine—and, I mean, I know why St. George leaves the personification of true religion to return to F--ry Lond, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how Spenser knew, or at least what Spenser knew, and wanted me as a reader to know, and it’s another of those weird bucks and hitches from out of time that keep kicking me loose from the poem and yet drawing me back all at once.

The other is Pynchon’s Against the Day, which if I were feeling glib I’d describe as Roszak’s Flicker meets Vollmann’s Bright and Risen Angels with a dash of let’s say Matewan; it’s like the reading and research I did back in the day for that never-to-be-realized mashup of Blavatsky and Lovecraft, Space: 1889 and the Difference Engine, all was homework for enjoying this—but such flippancy isn’t meet for any of the works in question. It’s baggy and shaggy and too much by half, I’m completely lost every time I slip back into it, but comfortably lost, reliably at sea, and the stew of language Pynchon and Spenser make when taken in alteration is heady indeed.

Heady, but thick, and slow-going, and see above re: work, and so these other books are piling up in the queue: John Ford’s last book, and Avram Davidson’s last Virgil Magus book, Mary Gentle’s Ash, the Moonday Letters and the Monkey’s Mask, the Underground Railroad and a half-dozen Queen’s Thieves, and that’s just the fiction, good Lord, there’s the White Mosque which isn’t even on my shelves yet, and Reading and Not Reading the F--rie Queene, which is, but, I mean, well...

As for what I have read, recently, well, I mean, there was Under the Pendulum Sun, which was fine insofar as it went, some lovely and divertingly weird imagery, but overall the book’s preoccupations weren’t my own, or rather weren’t what I would’ve expected them to be, given what we’re given, which resulted in some unfortunate undercooking here and gauchely overdoing it there and left me mostly with I’m afraid a shrug; and then there was Jawbone, which was spectacularly taut and exactly pretty much what I wanted it to be until it somehow utterly failed to end; and then there was, well.

Oh, it’s a big thick wodge of an epic, diligently working the post-Martin space, which is terribly au courant for epics, and it’s got a killer title, and that’s about all I can say for it—it has nothing like Ojeda’s power, or Ng’s charm, it sags tiresomely when it doesn’t race through suddenly ancillary quests for plot coupons (I’m afraid my disdain is such I’ll reach for overused critical terminology): an Anthropologie®-curated fantasy with a girlboss gloss that insists I see a dragon without doing the work to show me anything like a goddamn dragon. —But Shannon did make two moves, at least, that stuck with me, in how they kicked me loose, but without anything beyond my own cussedness to draw me back:

The first (which, as I’m piecing this together, I realize happens second in the book, but it’s the first I remember, so) is when great revels are thrown to celebrate the introduction of Sabran, our unmarried cod-Elizabeth I, to her proposed suitor Livelyn, our cod-Anjou:

The Feast of Early Autumn was an extravagant affair. Black wine flowed, thick and heavy and sweet, and Lievelyn was presented with a huge rum-soaked fruit cake—his childhood favorite—which had been re-created according to a famous Mentish recipe.

And at that I closed up the book, and looked about the bus (I was reading this almost entirely on the bus, in to work, and back home again), and then opened it up to the front to scour the maps—here, follow along—there’s the Queendom of Inys, or cod-England, and the Draconic Kingdom of Yscalin, or cod-Iberia, and the Free State of Mentendon, which I keep thinking of as cod-France, but is really more of a cod-Low Kingdoms (which makes doomed Lievelyn more of a cod–Holstein-Gottorp, I suppose); there’s cod-Lybia and a cod-Levant, and then over here on our other map we have wee cod-Nippon and but also the Empire of the Twelve Lakes, which is a cod-Middle Kingdom and not a cod-Minnesota—but what we don’t have is a cod-India, a cod-Cyprus, a cod-Madagascar, a cod-Madeira, a cod-Caribe, a cod-Hawai’i, not a cod-plantation to be seen—so when I read that a Prince’s favorite dessert is

a huge rum-soaked fruit cake

and you have countries and cultures and glimpses of history recognizably English and Spanish and Dutch and Japanese, and you tell me offhandedly you have rum, rum which if it is to be rum and not some phantastick honey liquor or something, but rum made from sugar, sugar from sugarcane (I mean, you can make rum from beet-sugar, but I’d hope you’d tell me it was beet-rum so I could take at least some visceral delight)—and sugarcane as such requires prodigious quantities of backbreaking labor to grow and harvest and process on a scale industrial enough to have enough left over to think to boil it into liquor, liquor enough that it might occur to a royal pâtissier, or banketbakker, to soak a fruitcake in a bottle’s worth to see what might come of it, you tell me that this is a thing in your world, but I look on your maps and I can’t anywhere find a trace of the God-damned Triangle—

—I’m gonna get flung right the fuck out.

The second move that stuck (which, again, now I’m looking at it, came first) is at once almost anticlimactically smaller and yet so very much more large: it’s a move made over and over throughout the book, but this was (for me, at least, at the time, for reasons) the most startlingly salient example, the one after which I could no longer ignore the bedevilment—it comes as Niclays Roos, disgraced alchemist and con artist, exiled before the novel begins from Mentendon to the lone Western trading post in Seiiki, our cod-Nippon, he’s being palanquined across the island to a mandatory meeting with the Warlord, and gets inexplicably dropped on his own in the middle of downtown Ginura, the Seiikinese capital, where he knows no one, nowhere, not hint of how to get to the Warlord, not a thing, until he coincidentally bumps into an old friend and colleague: Dr. Eizaru Moyaka, who, with his daughter, Purumé, had come some time before to Orisima, the aforementioned trading post, to study anatomy and medicine with this exiled Western doctor. Eizaru offers his modest house to Roos as a place to stay until the Warlord is ready, and Roos gratefully accepts; after all, he knows no one else here, nothing, no-how.

Eizaru lived in a modest house near the silk market, which backed onto one of the many canals that latticed Ginura. He had been widowed for a decade, but his daughter had stayed with him so that they could pursue their passion for medicine together. Rainflowers frothed over the exterior wall, and the garden was redolent of mugwort and purple-leaved mint and other herbs.

It was Purumé who opened the door to them. A bobtail cat snaked around her ankles.

“Niclays!” Purumé smiled before bowing. She favored the same eyeglasses as her father, but the sun had tanned her skin to a deeper brown than his, and her hair, held back with a strip of cloth, was still black at the roots. “Please, come in. What an unexpected pleasure.”

Niclays bowed in return. “Please forgive me for disturbing you, Purumé. This is unexpected for me, too.”

“We were your honored guests in Orisima. You are always welcome.” She took one look at his travel-soiled clothes and chuckled. “But you will need something else to wear.”

“I quite agree.”

When they were inside, Eizaru sent his two servants—

Wait—which the what, now?

We have a couple of academics living in a modest house—in the capital, on a canal, sure, nice little walled herb-garden, she’s answering the door herself, taking in an old friend on a whim, sure, but there’s a cat twining about her feet, and then, all of a sudden—servants?

This sudden, wrenching shift, the violent clash of assumptions, between what I’d expect of the class of a couple of modestly housed academics, worldly enough to travel to a distant, despised outpost for a chance to study with an exotically disreputable doyen, yet grounded enough to open their own door to visitors, and what the book was willing to prepare me to accept of their class, with the sudden irruption of these two servants, never named, never described, just there, to, to, I don’t know, to have done things, fetch water, keep the day’s heat at bay, lay out the food, deliver messages, to signal the class to which the doctors belong despite any other assumptions, to otherwise be ignored.

They’re of a piece, these similar ignorances: slipping a rum-soaked cake into a scene for the one set of connotations the word “rum” might bring, without taking into consideration all the others that freight the word; dropping a servant—two!—into a set-piece for no other reason and no other effect than that it is assumed servants of some sort must be there—a heedlessness severely detrimental to the building of a world.

But here’s me being awfully stern about an epic so—I’d say “slight,” I’d say “inconsequential,” but there’s stern again, and uncharitable. I mean, I did finish the dam’ thing, didn’t I? —And there, up above, did you catch it? When Virginia Woolf was telling us what we ought to do, and ought not do, before we set out to read the F--rie Queene? That we should “walk about London; observe the crowds; calculate the loss of life and limb; rub shoulders with the poor in markets—”

And who does it turn out to be are we, then, being addressed? And who, is it assumed, are not?

That mighty wall between us, standing high.

Over at Lawyers, Guns, and Money, Elizabeth Nelson presents a Jonbar hinge I never would’ve thought of: what if Merle Haggard had released “Irma Jackson” when he wrote it?

INT. HEADSPACE. DAY.

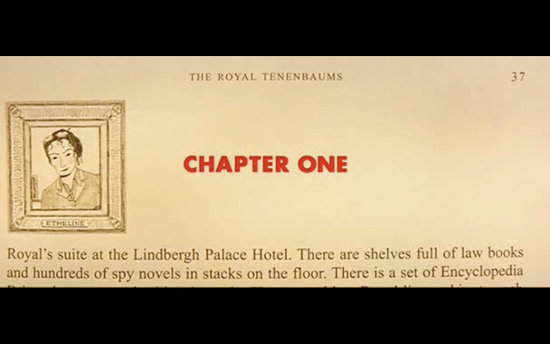

You know what’s really irksome about the Royal Tenenbaums?

It’s such an overtly, ostentatiously bookish film, from the inspiration for the grown-up whiz kids past their prime (everyone else will tell you it’s that Glass brood, but I’ll tell you it’s much more the ilk of Claudia and Jamie Kincaid and Turtle Wexler) to the obvious surface gloss of those exquisitely designed dust jackets, from the genially gravelly Narrator to the way it’s broken into chapters, with those primly typeset insertions—

—and there, that’s it, that’s what’s annoying: the text of the book we’re ostensibly reading as the movie unspools. If you read it (and it’s large enough to easily read, we’re given enough time), well. Ostensibility crumbles. —Oh, the first one, the Prologue’s okay: it’s just the Narrator’s opening lines, set down on the page and perfectly prosaic, excellently novelistic: “Royal Tenenbaum bought the house on Archer Avenue in the winter of his thirty-fifth year.” But the rest?

Chapter One as we can see starts off with “Royal’s suite at the Lindbergh Palace Hotel. There are shelves full of law books and hundreds of spy novels in stacks on the floor.” Chapter Four? “The side entrance of the hotel. Royal goes in through the revolving doors.” Chapter Seven? “The next morning. Richie comes downstairs. He carries the stuffed and mounted boar’s head.” The Epilogue? “A gentle rain falls in the cemetery, and the sky is getting dark.” —This isn’t the sort of prose to be found in books with those dust jackets, in novels written by Ellen Raskin or E.L. Konigsberg—these are passages from the screenplay of the movie that we’re watching, bald instructions to the production team, this is what needs to be seen to make the story happen, copied as-is and pasted just so, to lorem ipsum up a handful of grace notes in the movie’s art direction. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it, sticking out among all the other details so much more carefully considered. It irks.

I get a little twitchy, whenever the subject of cinematic writing comes up. —Cinematic writing, filmic writing, the screen-like æsthetic: here, let me grab a passage from Simon McNeil’s Notes on Squeecore, since that’s where I’m going to tell you it most recently came up:

Wendig is, perhaps, the clearest example of a novelist who writes in a filmic style. Now I think it’s important to draw out how I talked previously a bit about how this was a characteristic of Hopepunk—the mediation of a literary canon via its filmic representation being something I called out within the Hopepunk manifestos—but this isn’t so much a matter of Wendig mediating literature via its depiction on screens as it is Wendig drawing the screen structure back into the book. The crafting of an image becomes the chief concern of the novel in Wendig’s hands. Action is in the moment and the dialog is kinetic precisely because Wendig is trying to show his audience a moving picture rather than tell them a story. In a way the lionization of show, don’t tell, almost inevitably leads to the logic of a filmic literature. After all, internality often involves telling the audience how somebody feels. As “Show, Don’t Tell” becomes a hard rule, it’s not hard to see how an audience of would-be authors with an insufficient grounding in literature but a lot of exposure to television will inevitably interpret that to turn the page into a kind of screen.

Breezy, surfactant, imagistic, often in the immediately present tense and almost always the disaffectedly third person (first person in screen-like tips from teevee to vidya: first-person shooters, don’t you know): at its most amateurishly egregious, the iron law of SHOW DON’T TELL eats itself, as the prose insists on telling you the show that needs to happen in your head: bald instructions to the production team, as it were; passages cut and pasted from a screenplay. (Rather than show you a dinosaur, I tell you to see a dinosaur, to tie this to other ongoing threads.) —It can be intended as complimentary, to say of someone’s prose that it is cinematic, but there’s always a bit of English on the ball: oh, look, the writer’s trying so hard, the poor dear, to make prose do what it manifestly can’t—and anyway, everybody knows the book is always better than the movie. (Think of what it means, after all, what’s intended, when a television show is said to be novelistic.)

And, well, I mean, here’s me, then, and the epic: specifically imagistic, immediately present, disaffectedly third, cinematic, yes, okay, sure, filmic, all right, I’ll even cop to a screen-æsthetic, but only if I get to play with all the various meanings packed into “screen,” but but but I know what it is I’m doing, it’s not amateurish, honest, I’m sufficiently grounded and aware of if not all then at least a great many literary traditions—

See? Twitchy. And that’s never a good look on anyone.

I didn’t set down specific rules I’d follow, or at least not break, when I set out to figure out what I was going to do and be doing. It’s more that the rules assembled themselves, from what I wanted to pull off: an epically longform, episodic serial, and the best and most prevalent examples thereof at the time were superhero comics and hour-long dramedic television serials. So I leaned into that. —I’ve written before, about the differences between words, and moving pictures:

The primary difference between prose and cinema (beyond the obvious) is I think in time, and how each handles it; cinema (like theatre before it) no matter how achingly it might strive for universal generalities, must necessarily show you specific people doing specific things in specific places at very specific times. Prose, on its wily other hand, can say: “Monday morning staff meetings were always a chore for Willy” or “For the next week whenever she went to the coffee shop she saw the woman on the corner” or “And then everybody died.” —The narrow bandwidth of prose can’t begin to approach the wealth of incidental detail that makes up cinematic specificity without enormous slogging effort; most of the tricks and tips one needs to learn to tell stories and have them told with mere words, in fact, those reading protocols we’ve all had put in place, have everything to do with tricking us into thinking that specificity’s been achieved without us noticing (just as a great many of cinema’s tricks are all about forcing us to empathize with the saps up on the screen, bridging the vast gulf between their specificities and ours).

Setting out to ape the effects of one with the tools of another, though, is less about what I’m going to do (write with immediacy and specificity, as if, yes, I’m telling you what you’d see and hear if the story were playing out on a screen, yes yes) than what I won’t: generalize, pull back, sweep up and away from that immediate moment, that specific place. —And there’s one more thing prose does, that the epic does eschew:

Every narrative has a narrator. This may seem a ravelled tautology, but tug the thread of it and so much comes undone: a narrator, after all, is just another character, and subject to the same considerations. What might we consider, then, of a character who strives with every interaction for a coolly detached objectivity that’s betrayed by every too-deft turn of phrase? Who lays claim to an impossible omniscience, no matter how it might be limited, that’s belied by every Homeric nod? Who mimicks the vocal tics and stylings, the very accents of the people in their purview—whether or not they’re put in italics—merely to demonstrate how well it seems they think they know their stuff?

It’s only those texts that admit, upfront, the limitations and the unreliability of their narrators, that are honest in their dishonesty. —The third person, much like the third man, snatches power with an ugliness made innocuous, even charming, by centuries of reading protocols: deep grooves worn by habits of mind that make it all too lazily easy for an unscrupulous, an unethical, an unthinking author to wheedle their readers into a slapdash crime of empathy: crowding out all the possible might’ve beens that could’ve been in someone else’s head with whatever it is they decide to insist must have been.

I’d never presume to tell you what someone else is thinking, good Lord, no. That would be rude. Instead, I’m going to show you what it is they do, and say, and let you draw your own conclusions, and trust you to adjust them as we go.

Framing it this way, as what I’m not going to do, makes me mindful of the tools I’ve set aside, and turns those vasty fields untrampled into negative space—a very potent consideration in any composition: instead of showing you a dinosaur, or telling you to quick, think of a dinosaur, the hope is that these dotted moments, and the space implied between them, might at this moment or the next shiveringly resolve in your head into the suggestion, of a dragon-like, dinosaur-sylph—and all the more impactful, as it’s one you’ve made yourself.

A long way round, perhaps, but fitting, I think, for an idiom that seeks to immerse you in a slightly disjointed reality, to make you believe that at any moment a short sharp shock of the numinous might intrude. —At any rate: I’m having fun. The occasional twitch aside.

Actually, you know, the one for the epilogue’s okay, too? “A gentle rain falls in the cemetery, and the sky is getting dark.” That’s a fine-enough turn of phrase for a novel, or even a screenplay. Except of course for the fact that it’s not getting dark in the scene that then unfolds: the sky’s a fixed and dreary mid-afternoon. —The perils of adaptation, one supposes.

Civitas Aurelianorum.

So I’ve finally slowly been picking away at Treme, in part because I’m feeling a bit of a jones for some of the world below the Mason-Dixon, but mostly because I want that taste of systemically languid flânerie about a quintessentially urban warp and woof without, you know, all the fucking poe-leece the fucking Wire brings to the table (though there are still cops, of course there are cops, Jesus, the cops), and anyway: this point I’m making is entirely evanescent, but nonetheless: it is of some interest that the Baltimore of the Wire is, to the extent that it’s not only an inside joke, but a goddamn plot point, an insular world sufficient almost entirely unto itself, but—the New Orleans of Treme is almost from the very beginning dependent upon not nearly entirely but still to a surprising extent within the fiction coterminal with New York City. —But in the meanwhile, the car is making this very loud noise, and I’m supposed to be able to walk away from the day-job for a week-long vacation that involves a lot of driving just next week. But at least this verde margarita’s cold and spicy? At least.

In which, knowing nothing of necromancy—

I haven’t read Gideon the Ninth, and I’ll be upfront, here: I’m not all that likely to, which is really no skin off of anyone’s nose. This isn’t about Gideon the Ninth, or Tamsyn Muir, who I’m sure is a lovely person, for all I’ve never met or interacted with her. No: this starts off being about something somebody said to kick off a review of Gideon the Ninth:

A lot of the best recent science fiction and fantasy stories are notable for how well they color outside the lines. Disregarding genre expectations and freely borrowing tools from other literary traditions, a slew of writers are reinventing previously hide-bound forms. This is partially a progression of craft, but it’s also possible because of broader cultural phenomena—fantastical tropes, once restricted to a few niche markets, now dominate mainstream media. As a result, storytellers have to do less reinventing of the wheel each time they mix far-fetched elements—even the most general audiences don’t need the lore of vampires or zombies explained to them, so it takes very little narrative lifting to add such ghouls to an unexpected setting.

I’m not sure I can quite express how shiveringly wrong I find that passage, or the thought behind it, and I hasten to remind you that I haven’t read Gideon the Ninth, and so I cannot possibly be said to be saying that it is guilty of taking very little effort in its narrative lifting, just because it’s what someone else gestured toward when wanting to talk about it. —So I turn to what Paul Kincaid said, about another book I’m frankly not likely ever to pick up:

Actually, this use of language for effect rather than for sense, this notion that if you bundle enough images together somehow they will create an impression of something awesome, brings me to another problem I have with the story. There is a carelessness here that is evident both in the way the language is used and the story that the language is used to tell. When we are told, for instance, that “Red wins a battle between starfleets in the far future,” you wonder, given that the characters wander freely back and forth through time, what is meant by far future? Far future of what? That is thoughtless writing. But then, on the evidence of this story, I don’t think that either El-Mohtar or Gladstone has sat down to work out what a time war might be like and how it might be structured. Presumably Red and Blue are immortal (or at least as near immortal as makes no difference) agents who travel backwards and forwards through time changing events in order to create a different future that favours their side. So far so simple, but then Red tells us that “strands bud Atlantises to thwart her,” that 30 or 40 times she has walked away from a different sinking island. So there are multiple timelines; changing one event doesn’t change the future, it just births a new timeline. In which case, what are they fighting for? What could possibly constitute a victory, or a defeat, in such a situation. If everything goes wrong, then there is another timeline where everything has gone right. And if there can be no victory, there can be no cause for war. How do you go to war with an enemy who has just got everything they want in a different timeline? Over and over again throughout the novel I came up against the same notion: that none of this makes sense. There is a time war not because there is any functional purpose in the war, but because the authors need their two lovers to be on opposite sides in a conflict. This is Romeo and Juliet with two Juliets but otherwise no change: starcrossed lovers on either side of an age-old quarrel they cannot repair, needing to keep their affair secret, and leading to seeming death. Make the houses of Montague and Capulet into the enemy camps in a time war and lo you render the whole thing science fiction.

Which not only gets at the shortcomings of sidestepping such narrative lifting, but also demonstrates how pervasive that sidestepping is, or has been, or could become, in SF as it’s currently spoke, and begins to get at how frustrating those sidesteps can be, but, I mean, you don’t need me to tell you that, you saw WandaVision, right? —So I turn to what William Empson said, about old bad poetry: “This belief,” he said, of the notion that atmosphere—the taste left in the head—is all, and conveyed in some fundamentally unknowable way as a byproduct of meaning, independent of grammar, unsusceptible of analysis:

This belief may in part explain the badness of much nineteenth-century poetry, and how it came to be written by critically sensitive people. They admired the poetry of previous generations, very rightly, for the taste it left in the head, and, failing to realise that the process of putting such a taste into a reader’s head involves a great deal of work which does not feel like a taste in the head while it is being done, attempting, therefore, to conceive a taste in the head and put it straight on to their paper, they produced tastes in the head which were in fact blurred, complacent, and unpleasing.

The taste in the head—the sylph—is the shiveringly unspeakable concatenation of desire, doubt, belief, of wonder and of terror, brought on by seeing a dinosaur; one does not put down that taste merely by showing the audience a dinosaur. You can’t make me feel like I’m in a room with a vampire by telling me a vampire has entered the room. The narrative lift is all. —And if it turns out your narrative lifting is up to the task of making me feel the actual staggering weight of walking away from thirty or forty sinking Atlantises (why else reach for such overkill?), one after an apocalyptic other, or putting me in the same room as a snarkily magical génocidaire, well. —It’s not you, honest. It’s me. Maybe I’m getting old.

#HarshWritingAdvice.

I need you to understand when they tell you “The stakes aren’t high enough,” they don’t mean: make the stakes higher. Sweep it all up. Go big or go home. They mean, “Make me give a fuck already about what the hell’s already at stake.”

A Song of Graphs and Quants.

Why were the novels of Game of Thrones so popular?

I don’t know, ah—okay, so, an experienced wordsmith well-connected in both the publishing and entertainment industries had the good fortune to have put out the third book of his well-enough received epic fantasy just as it became clear Peter Jackson had bottled a rather prodigious quantity of lightning with his filmic adaptation of Tolkien’s epic fantasy, leading to just about every half-viable piece of epically fantastic IP getting optioned by this production company, or that; being well-connected, but also experienced, said wordsmith was able to negotiate the sort of deal with the sort of people more likely than not to make a passably decent go of it; said go was made, a television serial, in time to catch enough of the lightning coming down from Jackson’s movie high, hungry for more, that it was given time enough and clout to build on that audience: thus, popularity, to such a degree that now everyone refers to “the novels of Game of Thrones,” which is the name of the since-concluded television show, and not “the novels of A Song of Ice and Fire,” which is the name of the as-yet unfinished series of books.

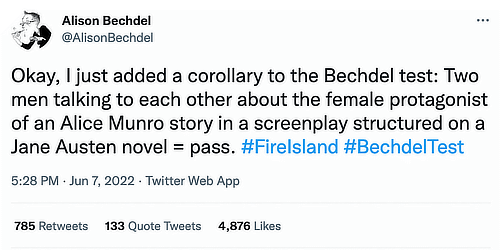

A new study from @PNASNews suggests one reason why @GRRMspeaking’s A Song of Ice and Fire was such a hit—the average number of social interactions main characters have, chapter-to-chapter, is just like real life.

Or, sure, okay. Maybe that’s it.

There’s lies, damn lies, statistics, and then there’s stuff like this, which has gone through a couple of waves of popular acclaim in the sorts of circles on social media that go for, you know, network science, and data analytics, and doorstopping wodges, and premium cable sexposition. —It doesn’t lie, no, and certainly there’s not the faintest whiff of damnation about it, but a whole lot of mathematical wheels are set to spinning with a great deal of show and rapid-fire patter, and the crowd does cheer for a moment or a tweet to see it run, but it doesn’t get us much of anywhere at all when the dust settles.

Significance: We use mathematical and statistical methods to probe how a sprawling, dynamic, complex narrative of massive scale achieved broad accessibility and acclaim without surrendering to the need for reductionist simplifications. Subtle narrational tricks such as how natural social networks are mirrored and how significant events are scheduled are unveiled. The narrative network matches evolved cognitive abilities to enable complex messages be conveyed in accessible ways while story time and discourse time are carefully distinguished in ways matching theories of narratology. This marriage of science and humanities opens avenues to comparative literary studies. It provides quantitative support, for example, for the widespread view that deaths appear to be randomly distributed throughout the narrative even though, in fact, they are not.

Eh. —Two empirical claims are made: that the cast of characters and the social networks formed within the books therefrom comport with the sorts of networks observable in the real world, and theoretical cognitive limits of association such as Dunbar’s number; and that the distribution of the deaths of notable characters appears random within the discourse time of the story, but comports with a power-law distribution when charted against the fictional calendar of story time, similar in value to those of real-world human activities. —From these, an implication is drawn: that the perceived quality of the books is due at least in part to how they fulfill these two claims. (Oh and but also: our research is cool and worthwhile and you should cite it so we can do more of it, but that usually goes without saying.)

The first claim, then, which is based on a dataset “extracted manually” by one of the authors “carefully reading” the books over several months, noting each character and every interaction between them, and entering the data into spreadsheets divided per book and chapter; interactions being defined as either a meeting portrayed in the text, or when the text makes it clear that the two characters had at some point interacted. (“In case of doubts regarding the data,” we are told, opinions were “calibrated through discussion. Consensus assured that no automated calibration method was required.”) —This process resulted in a network graph you might’ve seen running around:

All told, 2,007 unique characters were tabulated from the five books written to date, of which 1,806 have interactions with at least one other character, which raises any of a number of questions about those 201 solipsists, like who were they, and what were they up to, and do they raise any questions themselves about the methodology used to determine and count up interactions, but we breeze right by these to learn that the average number of characters appearing in any chapter fluctuates quite a bit, but averages around 35, the typical size of (contemporary) bands of hunter-gatherers, the cast of your run-of-the-mill Shakespeare play, or an English literature department; that main characters tend to have larger networks of interactions than other characters (or is it that characters with larger networks of interactions become main characters?); that the networks of point-of-view characters tend to average right around 150 or so: pretty much Dunbar’s number; and that these networks tend to have a high degree of assortativity, a quantitative measurement of homophily—a feature of real-world social networks, like liking like—but assortativity’s measuring pretty much whether nodes with lots of links tend to link to other nodes with lots of links, and not so much, you know, whether the node’s from Westeros, or the Free Cities, or whose point of view is the chapter they’re in at the moment.

I’m not here to quibble with their figuring—I can barely tell a python script from a hypnotized snake. What I’m here to quibble with is what’s done with them, or rather what’s thought to have been done with them: after all, as we’re told, the paper suggests the books are a hit at least in part because the number of social interactions entertained by the main characters mirrors those you’d see in real life—but. But:

- It’s not demonstrated that this quality is necessary for works to be popular;

- it’s not demonstrated this quality’s unique to these books, or to popular books as a general rule.

We’ve got a dataset, and a description of a dataset, and some gestures towards comparisons with other, possibly maybe similar sets, but in very limited contexts: we are pointed toward Shakespeare (always a sign of Quality), but only in comparing the average number of characters per chapter to the average cast list of two hours’ traffic of a stage; we are pointed toward the social networks to be found in more mythic sources such as Beowulf, the Táin, the Iliad, various Icelandic sagas (mostly to the detriment of Beowulf and the Táin)—aaand that’s about it.

The study “suggests,” perhaps, to be sure, but no work’s done toward such a suggestion. —Perhaps instead it’s true that, much as with plots, or dialogue, a certain degree of simplification and stylization in the social networks of sprawling casts turns out to be a hallmark of popular serials and epics, and A Song of Ice and Fire succeeds in spite of its verisimilitude on this point, and not because of it. —Perhaps instead it’s the case that this vaunted verisimilitude is basically an epiphenomenon: that (without conscious effort otherwise) things built by human brains tend to comport to the patterns and limits inherent to things human brains can build. Without directly comparing this dataset with other datasets also “manually extracted” from other works, we can’t even begin to know which way to turn, much less begin to suggest we hare off in that direction.

Instead of comparing the average cast sizes of chapters and plays, why not more directly compare the network graphs of these books with those generated by the intertwining casts of the history plays from Richard II to Richard III–plays directly about, after all, one of the stated inspirations for Ice and Fire. Instead of borrowing the glory of such stonkingly obvious Paragons of Quality (mythology! Shakespeare!), why not compare them against those of other epic fantasies: Tolkien, sure, okay, but also Ice and Fire’s far more direct progenitor, or neighbors such as Eddings, Jordan, Donaldson, Lackey, Elliott, Hobb, or Kurtz. —Hell, we’re splashing about in the digital humanities: imagine what we might’ve learned by comparing the network graphs of the books, with those generated by the television show!

There are even implications within their dataset that could be teased out into something more than a suggestion. We’re told, for instance, two kinds of interaction were noted: either explicit, or implicit. What’s the overall distribution of these two types—more of the one, or the other? About even? Are there characters whose networks buck these averages? If so, which way, and by how much? And are these characters of a certain type? —We don’t know. (Peering at the data itself, it looks like they didn’t record whether an encounter was explicit or implicit—but they did note whether an encounter was friendly, or hostile, which raises further questions admittedly beyond the scope of this already sprawling epic.) —And there’s a rather definite bobble in their network graphs just after [SPOILER] the Red Wedding, described as a “suppression of assortativity,” but it’s mostly written off as a side effect of the close third person: “The deflated degrees of the masses relative to POV characters decrease homophily,” which, well. Is a degree of wistfulness I hadn’t expected to encounter in such an objective paper.

The second claim, regarding the distribution of the deaths of notable characters in discourse time as opposed to story time, is far less interesting—far more a case of looking for your car keys under the streetlight, or measuring only what the ruler you have in your hand can measure, and not what you need, or what’s actually there. To be sure, the distinction between discourse time and story time is an important one, thank you, Russian formalism, and it’s a useful crowbar to pry at Ice and Fire with, given its interwoven back-and-forth structure. And deaths, even in epic fantasy, are usually precise and unambiguous events—easily totted up. But the butcher’s bill of this study starts off at a steep discount:

We now turn to consider interdeath story time and interdeath discourse time to reveal an interesting difference between the underlying chronology and how the narrative is presented. For this purpose we consider only deaths which we deem to be significant. These are deaths of characters in the network who appear in more then one chapter. We apply this criterion to avoid the inclusion of the deaths of “cannon-fodder” characters whose main purpose in the story is to die immediately after they are introduced.

“The kings, the princes, the generals and the whores,” as Martin himself said at one point; “But few of any sort, and none of name,” to drag Shakespeare back into this for a moment. —But much as you have to start somewhere, you have to stop somewhere else, or you’ll never be able to count it all, and the attentions that must be paid to protagonists over and above the spear-carriers and supernumeraries are injustices also beyond the scope of this too, too sprawling post. So we will accept their limitation, it’s precisely defined, not subject to subjective notions of significance, however much we might rankle at “cannon-fodder.” —In terms of story time, the deaths are fixed to a timeline compiled by fans, thank you, crowd-sourcing, with necessary assumptions and approximations as noted; in terms of discourse time, though, the deaths are indexed according to, uh, which chapter they appear in. —That’s it. In terms of the “memorylessness” (a term of art doing a lot of unfortunate work in this context) of the interevent discourse time between one death and the next, it’s entirely down to the number of chapters between them. And I mean choosing whether to put an event in this chapter, or that? Is definitely a choice to be made, with effects to consider—but it’s considering structure at a strikingly crude level.

It is one that’s easily tabulated, though.

I mean, we know why the authors of this study went with character deaths, and tried to find some objective measurement of shock, or surprise, when analyzing Ice and Fire. They tell us why, themselves:

A distinguishing feature of Ice and Fire is that character deaths are perceived by many readers as random and unpredictable. Whether you are ruler of the Seven Kingdoms, heir to an ancient dynasty, or Warden of the North, your end may be nearer than you think. Robert Baratheon met his while boar hunting, Viserys Targaryen while feasting, and Eddard Stark when confessing a crime in an attempt to protect his children. Indeed, “Much of the anticipation leading up to the final season [of the TV series] was about who would live or die, and whether the show would return to its signature habit of taking out major characters in shocking fashion.” Inspired by this feature, we are particularly interested in deaths as signature events in Ice and Fire, and therefore, we study intervals between them.

“Signature events,” rather like the chintzy mint on the pillow provided by a chain hotel as part of its Signature Service, or the ghastly Signature Desert the front office wants waitstaff to push this month. —Let’s face it: there are really only two deaths, or death-laden events, in Ice and Fire that shock above and beyond the usual thrills and chills expected of any blood-soaked melodrama: the [SPOILER] Red Wedding, and the execution, at the end of the first book/season, of Eddard “Ned” Stark. And I guaran-damn-tee you, it wasn’t the memorylessness of the interevent discourse time that led to the surpassing jolt of either of those events: it was the fact that the sprawling epic had taken the time and effort to set up Ned, and Robb and also Catelyn, as protagonists, with all that that implies; the implicit promise of the stories we thought they were going to get was suddenly and rather brutally forestalled—and it’s that violation that juices the shock. The trick of it is to lend a patina of that shock to all the other deaths that are dealt in the course of the story; the bind is that, as the story progresses, the “real” protagonists become clear—and it’s clear what won’t be happening to them. —That bind’s an enormous part of why so much tension evaporates from the later seasons of the show; it’s also quite possibly one of the barriers to finishing the books at all.

But this is all my subjective opinion, though. It’s not like I’ve measured it objectively or anything.

But enough of this! (Too late! wail the punters; I tip my hat.) —If I’m hungry for more analysis of these books, I’ll more than likely to turn to something more like this in-depth analysis of the depiction of the Dothraki than any more network analysis. Once again, I’d aim a kick at this unfortunate XKCD strip:

Working with objectively measurable quanta is not only easy, it’s sometimes deceptively useless.

Inter os atque offam.

There’s a world worth examining between this particular sentiment—

TV cannot hold its own against reality. David Simon gets the closest.

—and this critical apprehension:

Created by Maryland native David Simon and Seattle native Eric Overmyer, the show hasn’t unpacked the received cultural stereotypes of the city so much as fine-tuned those stereotypes through compulsive attention to documentary detail. Treme dedicates itself so totally to showcasing unique local color at the micro-level that it transforms New Orleans into a weirdly hermetic dreamland—a gritty, self-celebratory refuge from the dull forces of mass culture, where characters walk around saying things like, “Po’boys aren’t sandwiches, they’re a way of life!” and “Where else could we ever live, huh?” In Treme’s world, brilliant jazz trumpeters are more interested in barbecue than fame, voodoo-Cajun bluesmen sacrifice live chickens on the radio, and fast-food chains exist only when junkie musicians need a paper sack to camouflage their stash. When Black people die, they’re given rousing jazz funerals; when white people die, their ashes are sprinkled into the Mississippi River during Mardi Gras. Few moments in the show exist outside of its notion of what New Orleans represents in contrast to the rest of the United States.

Every deed must formulate a gesture, but the gesture’s not enough to do the deed. —However delicately the lip might be painted, however intricate the figuring of the cup, it’s all for naught if wine is never sipped. (The trick, of course, is figuring out what’s cup, what’s lip, which the wine, and which the sip. It’s different every time you do it—and there, that’s the clomping foot of the world.)

Ornament is not only produced by criminals, it itself commits a crime.

Go, read Vajra Chandrasekera on why it is we’re told to kill our darlings, and what it is we’re taught to listen for, when we want to know if it sounds like writing, and then go read Ray Davis on Swinburne, who sounds a lot like writing, and loved his darlings not wisely, but altogether well. —“Soon the streets of the town will glisten like white walls. Like Zion, the holy city, the metropolis of heaven. Then we shall have fulfilment,” sure, sure. We all know how that turned out.

Fully automated hauntology.

I do wonder how authors dealt with the memories of cities and the ever-changing fabric of their ever-present selves in the days before we had Google’s Street View, and specifically now the history slider, letting you slip back and back to see what it looked like the last time one of those camera-mounted cars wandered these same streets, or the time before that: oh, look! you say, cruising past your own house on the monitor of the computer within it. Our car was parked right out front that day. What a curious sense of pride. (—If I were in my office instead, I might look up to see the enormous map of Ghana on the wall, and decide to walk the streets of Accra for just a few minutes to clear my head; we can do that, sort of, now.) —But there are costs, and slippages: this morning I was trying to find an appropriate bus stop to loiter at, needing to catch the no. 6 bus up MLK to (eventually) Vanport; I was reminded they’re building a building there now, where once had only been a parking lot, and a Dutch Bros. coffee cart, and happened upon a view of the construction site from April of 2019, when the first floor had been set in concrete and rebar, waiting for six more wood-framed storeys to balloon above it, but I stepped sideways, into another stream of views, that only offered September or June 2019 (the wood having bloomed now clad in brick, or what passes for brick these days) or August 2017 (the lot, the coffee, the light already different, as if lenses have changed enough since then to be noticed), and so here I am, with a morning spent bootlessly wandering over and over the same corner and streetfront, trying to find the precise spot from which I can once more catch that bygone glimpse of April, of last year.

Failsons & November criminals.

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay! It’s the thirty-fourth anniversary of my radicalization, which I can date with such alacritous precision due quite simply to the fact that it in turn is due to a comicstrip:

It was more of a straw and a camel’s back than a short sharp apocalypse: and it’s not like there wasn’t then or isn’t even yet a long ways left to go (not too much later, I found myself at Oberlin, tut-tutting my fellow students’ embrace of John Brown, whom I, ’Bama boy that I am, took, at the time, to be a righteous but nonetheless terrorist)—but, but: I’d wet my feet in a Rubicon. We could’ve been making the world a better place. We chose not to.

Thinking about how much of what was then recent history I learned back in the day not from lectures and classwork, from school, but from nipping off to the library to dig through Doonesbury collections, augmented by archives of Feiffer and Herblock and, well, yes, MacNelly, one must have balance, one supposes.

Thinking about that because of what Pat Blanchfield says in this snarkily “Bruckheimer shit” walkthrough of the latest instantiation of the (wildly popular) (wildly deranged) Call of Duty franchise—

A quarter of a billion people, whatever, have played these games, um, and so many American men do, one of the few ways a lot of people ever learn anything even resembling, like, the existence of this history, like, for example, like, in the last game, we were in Angola, is through these games.

Sobering, and not just for the ideology the games are steeped in, Dolchstoßlegending this or that regrettably unpleasant incident from Yankee history into thrillingly deniable covert ops that left the world, our world, far better off than it otherwise could’ve been, and don’t you forget it— not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

—(and also, yes, all the guns and the shooting and the extreme violence and all that stuff). —It’s, and I use the term advisedly, a cartoon: both in the sense that it’s deliberately, expressively, ruthlessly simplified, drawing power from its crudely broad strokes, and also in that it’s deliberately, ostensibly disposable: a work of paraliterature no one could ever take seriously, c’mon, a staggeringly elaborate, kayfabily po-faced act of kidding-on-the-square, a deniable covert op that leaves us thinking all unawares with precisely what it is we’ve been laughing at, for however long we’ve been twiddling our thumbs at the flatscreen.

Anyway. Down with all Commander Less-Than-Zeroes, wherever they might be found. Give me a November criminal any goddamn day.

Regrets, I've had a few.

Most notably, today, at this moment, the fact that I went the one way, when I coulda gone the other, which, granted, okay, kinda a foundational, even definitional experience of regret, sure, but anyway, back when we were tussling over questions of belief («belief» belief BELIEF) and the foundations, the definitions of fantasy and SF, I mean, I kinda wonder what might've happened if I’d leaned harder into the notion that SF is an argument with the universe, that fantasy is a sermon on the way things ought to be, because an argument’s a tool, a machine of words and logic that might be deployed with whatever passion or skill you care to bring to bear, or don’t, and so matters of “belief” are almost incidental (almost)—but a sermon, a real pulpit-pounding barn-burner of a stem-winder, hell, that pretty much requires belief: but not belief as in some positivist notion that what one posits is what one takes to be “real” (I once told my paramour at the time of how, during that first acid trip, I’d heard f--ry fiddles playing as streetlight scraped over frozen grass; but really? she asked, did you really hear them? Really? —We broke up sometime later); no: belief as in conviction, as in the indisputable fact that one knows the way things ought to be, and because the sermon ought to be, it necessarily addresses a world that isn’t: a belief, therefore, in what can’t be believed. —You want it to be one way. You want it to be one way, but it’s the other way. QED.

The visible world is merely their skin.

Altogether elsewhere, an interlocutor described the work of someone whom I haven’t read, for reasons, as, and I quote, “filmic and competent and all surface. And all the epigraphs only makes things worse,” and I know, I know, it has nothing to do with me, per se, but still: I felt so seen. —I do wonder, sometimes, as to how and why and the extent to which I’ve decided that the thing-I-do-with-prose should be so devoted to things prose is not supposed to do, but it’s like they say: anything worth doing is worth doing backwards, and in heels. [Strides off, whistling “Moments in the Woods.”]

Manichæan.

I might’ve made a mistake when I began the thing-that-argues. —Because I could not hear myself constantly and on a regular basis referring to Jo as a white woman (or, God forbid, a White woman), it would not be fair to single out Christian, say, by referring to him as a Black kid, or to Gordon as a black man.

Because I would not mark all of them, I could not mark any of them, so as to mark them all the same. The logic’s ineluctable.

But, you know. Logic.

It’s not just a matter of black, or Black, and white, of course. —How would you go about marking Ellen Oh? Would you say she is Korean? Even though she was born in Alabama, and most of her family hasn’t lived in Korea for a couple generations now? (Can you specify to any useful degree the differences in appearance between all possible individuals whose forebears might at one point have been sustained by that mighty peninsula, and the appearances of anyone, everyone else, that would render such a marker immediately perceptible, and adequately useful?) —You might perhaps think “Asian” to be an acceptable compromise, as a marker, but look for God’s sake at a map: Asia’s everything east of the Bosporous. How staggeringly varied, the appearances of everyone from there, to there! Worse than no mark at all, distorting marker and marked, and to no good or necessary purpose.

(The Ronin Benkei was flatly Japanese, even though Farrell was much too polite ever to notice more than a few echoes of classical Japanese manners in the gestures of Julie Tanikawa, whom he never heard swear in Japanese, except that once, for all that she spoke it as a child, with her long-dead grandmother.) (And as for Brian Li Sung—oh, but comics have their own markers, at once far more persnicketily precise, and yet so roomily ambiguous, and I’ve said too much.)

It’s not that the characters aren’t marked at all, of course: just not with such totalizing, reductive, contingent signs. Everyone’s described in much the same manner: their clothing, the way they carry themselves, their hair, how they say the things they say, the way the light hits them (the visible world being merely their skin)—the hope, of course, being that these pointilist details will accrete into a portait in the reader’s mind—inaccurate, perhaps, at the start, but resolving over time toward something more and more like what’s intended. (—Or, to be precise, what’s needed to make what’s intended work; this is imprecise stuff, this work, but really, think about it: how could even a single person, that is so large, ever fit within a book that is so small?)

But what does such a cowardly refusal on the part of the narrative voice, to plainly mark what any other medium would’ve plainly marked, by virtue of not being limited to one word set after another—what does this do to a reader’s relationship with the portrait they’ve been assembling when it suddenly must drastically be rearranged, after thousands upon thousands of those words? (I mean this at least is gonna hit a bit different than Juan Rico offhandedly clocking himself in a mirror on page two hundred and fifty.)

But let’s turn it around a minute: is it my fault if you didn’t assume from the get-go that an un(obviously)-marked character in a novel written by a white man, in a rather terribly white idiom, set in one of the whitest cities in the country—is it on me if you’re the one who assumes, before you’ve been told, that this character’s clearly white?

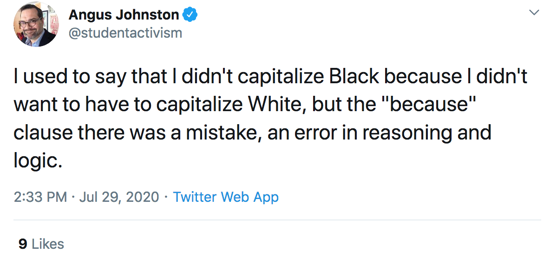

My own take on the question of the moment, or at least of the moment when I began sketching this out (though I’ve been thinking about something like it for a while now; it might’ve been the foreword of the third book, had anything coalesced in time)—my own take is not unlike what’s laid out by Angus above: because I would not dignify the constellation of revanchist grievances, the cop’s swagger and the supervisor’s sneer, that make up the bulk of what passes for the race I could call my own—because I would never capitalize that—well. Logic demands. Right?

But it’s ad fastidium, is what it is. —I could bolster it with an argumentum ad verecundiam, by turning to what Delany’s said, on his own perspective on the subject, bolstered in turn by Dr. DuBois’:

—the small “b” on “black” is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent, a significance that many young people today, white and black, who lackadaisically capitalize it, have lost track of—

Oh, but that was written in 1998, which is further away than it seems. Which is not to say anything’s changed, good Lord, I wouldn’t know, I only ever had breakfast the one time with the man, and we mostly talked about Fowles. But then, there’s this, from 2007, or 2016, depending:

“And those aren’t races. Those are adjectives of place—like Hispanic. And Chinese. Caucasians are people from the area in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which is where, at one time—erroneously—white people were assumed to have originated.”

“Latino..?”

“And that refers to the language spoken. So it gets a capital, like English and French. There is no country—or language—called black or white. Or yellow.”

But when he told this to a much younger, tenure-track colleague, the woman looked uncomfortable and said, “Well, more and more people are capitalizing ‘Black,’ these days.”

“But doesn’t it strike you as illiterate?” Arnold asked.

In her gray-green blouse, the young white woman shrugged as the elevator came—and three days later left an article by bell hooks in Arnold’s mailbox—which used “Black” throughout. He liked the article, but the uppercase “B” set Arnold’s teeth on edge.

And yes, it’s much the same argument! But it sits very differently, with different emphases and outcomes, when it comes from the mouth of Arnold Hawley, such a very fragile man—not Delany’s opposite, no: but still: his reflection, seen in a glass, darkly, as it were.

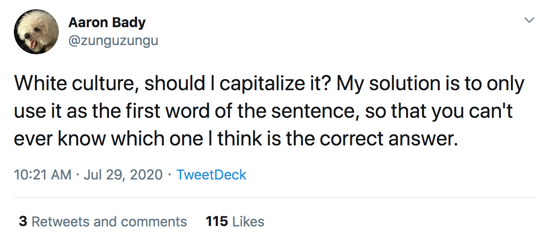

(Everyone knows there is no country called black, or language. What capitalizing the B presupposes is: maybe there is?)

But my own take on whether to capitalize “black” has no bearing on the thing-that-argues—in part because I’ve short-circuited it entirely, yes, but also and mostly because none of the people in it give a damn what I think, nor should they: the thing-that-argues, when it turns its attention to any such matter, should only ever care what it is they think, and how, and why: Christian thinks of himself as a Black man, for all that Gordon sees him as a black boy; H.D. sees herself as a Black businesswoman, concerned as she is with Black businesses; Udom, the new Dagger, still thinks of himself as from Across-the-River, though he knows most everyone these days sees him as one of the Igbo; Zeina, the new Mooncalfe, would probably say she’s black, or crack a bleak joke about Atlantis, and drowned mothers-to-be, or maybe she’d punch you, I don’t know; and Frances Upchurch (though that is not her name) would tell you exactly what you’d think she would, and never you’d know otherwise. —And each of them must be able to believe what they believe, to fight for it, or change their minds, without ever having to worry about some quasi-objective narrative voice thinks maybe it knows better blundering up to flatly gainsay them, this white voice in a terribly white idiom telling each and every reader that this was said by a Black man, or that was thought by a black woman, tricking these readers, every one, into thinking they maybe know what the author thinks—or worse, what the thing-that-argues thinks—and thus, what ought to be right, and further thus, who should be, could be, must be wrong. —And this understanding extends to all things.

(The narrative voice of Dark Reflections does not capitalize “black,” when referring to jeans, or to people, and so we can think we know what the author thought just a few years ago, or at least his copyeditor.)

So maybe I made a mistake at the start of it all. But there was thought behind it? At the start? Reasons to have done it, not that those are a guarantee of any God damn thing. —Maybe I’d do it differently, I were setting out today. Maybe I still regret using quotations marks, or writing it down as “Mr.” instead of “Mister.” But here we are.

There is a strength in writing as a fool, you do it right. Talking outside the glass. The room, that negative space affords, for the characters, for the story, for the readers (or so I tell myself, but I am a fool)—there’s power, in setting a taboo like this. You may not talk inside the glass, but still: you spill enough words, the shape of the glass can start to be made out.