Talent on loan from God.

Really looking forward to the day I manage to think about Charlie Kirk as often as I think about, ah, that other guy. Also a prick. Also dead.

For a good return you gotta go bettin on chance—and then you’re back with anarchy.

Just so we’re all clear: the City of Portland is removing protections legally applied and mandated by law in an attempt to prevent the utterly and thoroughly illegal rescission of three hundred and fifty million dollars’ worth of federal funding, legally allocated by the duly elected representatives of the people who put up the funds, all because no one can afford the amount of time it would take for the wheels of justice to slowly grind their way to finding precisely that illegality and impotently enjoining what’s already been rescinded until such time as the Supreme Court throws out any such exceeding fine work without explanation from the illegible gloom of the shadow docket, but—but! Having done so, the entire city must now spend the rest of the year, the term, the reich huddled quietly in a corner hoping this will all be enough, but it’s never enough, and anyway if at any later point we happen across his mind in the slightest slantwise fashion he’ll just take it all again, and more besides, and what will we give up next?

Thamus Agonistes.

“Now that people are turning to ChatGPT for spiritual insight, though, I wonder if I finally have to admit it. Obviously here again we are dealing with what seems like a quantitative change—people are using the machine to shuffle religious clichés, where previously they just half-consciously did it themselves. But the qualitative difference is that the insights of ‘Buddy Christ’ could always be corrected against the unchanging text of Scripture. When there is no longer an external anchor like that, when the divine revelation is ‘customized’ for each and every reader, something has changed. Again, this is not to say that what happens to be in the Bible is necessarily ‘better’ than any given ChatGPT transcript—presumably it’s often worse. But a point of leverage has been lost. Counterargument is no longer possible in the same way. And insofar as that point of leverage, that external source of authority, was how ‘God’ functioned in traditional monotheism, that means God is dead.” —Adam Kotsko

When you get caught

Between the Moon and

Second person, chat. I just don’t know. —Oh, it can be done well, anything can be done well, but the curve on second person is some kind of steep. Comes in three basic flavors, the second person: there’s what you might call diegetic second, where who’s being addressed is a specific second person, firmly ensconced in the story as a character themselves, so that it’s really more of a text within the text, you’re distanced from the point of address—it might as well be an exchange you’re eavesdropping, an epistolary you’ve somehow intercepted. —The next you might call more of a diffuse, a second person that, yes, is addressed to you, Dear Reader, but not too specifically: there’s entirely too many of all of you, and far too wonderfully varied; best to be disarmingly vague—and so, in an heroic effort not to break the spell, it can all-too-often never manage to cast one in the first place. —The third second person? Direct: an attempt to square the circle and have it all, the author reaching out of the text to grab you, yes you, Gentle Reader, by your lapels, but also the author would insist on the lapels to be grabbed, the type and tailoring, the heft in the hand, particular lapels suited for the specific you the author has in mind, a you you’re dragooned into playing, will you or nill you: it can’t help but hector, this voice, and no one likes being hectored, though even this can be done effectively, even well—one thinks of Eddie Campbell’s How to be an Artist, told in a striking second-person imperative, but that’s comics, and there are so many other things happening to détourn that voice. —Like I said. It’s hard.

So when I tell you The Spear Cuts Through Water is written in the second person—

(“You were thirteen, you think,” you’re told, quite imperiously, and I don’t know about you, but while I’m game enough to pretend to have memories I’ve never had, I’d just as soon decide for myself how reliable they are. Though I must admit I remembered this particular directive as landing rather more forcefully that it does upon re-reading; I was surprised by how—mild?—it turned out to have been. Thus, a grain of salt.)

—I mean, it isn’t, not really: it’s actually a first-person text. I mean, yes, every narrative is necessarily written in the first person, but Spear’s only somewhat coy as to this fundamental truth: your narrator’s there, on the page, on the stage, referring to themself always in the third person as “this moonlit body” (never “a,” or “the,” or “that” moonlit body, but always and reflexively “this”): the love-child (soi-disant) of the Moon and the Water, impresario and headliner of the showstopping antics of the Inverted Theater, that reflection of an impossibly tiered pagoda floating on the surface of the Water, bathed in the light of the Moon.

This is the structural triumph of the book, and what I greatly admire: that the epic as such is a theatrical production, drama and dance performed in that Inverted Theater in a dream that you’re having, told to you, narrated necessarily because it’s actually unfolding from the pages of the book in your hand, written by Simon Jimenez, but set that aside, because as you’re dreaming the story you’re reading, this moonlit body reminds you of your memories, memories of your much-later life that spark, that are sparked by, incidents in that story, this epic of the old country from so long ago. These layers add a richness that carries what’s really a rather focused (and single-volume) work just over the threshold of epic, but the movements between and among them are so surefooted that you’re never lost, never bogged down in metashenanigans: you marvel, instead, as background characters, bit players, minor figures, NPCs (in the [shudder] parlance of our [shudder] times)—as the story’s performed, the actors playing them in the Inverted Theater will step up to speak for a moment, a passage, a phrase, a snatch of internal monologue become spotlit soliloquy, a bit of italicized free indirect slipped in to trouble the narrative flow, to comment, contest, open it up, all these non-protagonists, from the usual monotone of one word set carefully, deliberately after another toward something more of a polyphony. Such a simple trick! But deceptively so: it’s only the theatrical conceit that allows it to work as well as it does, the artifice of performance excusing the artifice of italics, and of the courtly stilt needed to better fit with the flow of this moonlit body’s narration—appropriate enough for an epic, to be sure, but not so much for a glimpse of a stream of consciousness, unless, of course, that stream’s been polished by rehearsal, shaped and timed to fit: a performance, each of them, however glancing, however brief.

Marvel, then, and marvel again, as, once established, these moves are elaborated: the Moon’s dialogue, say, which is handled the same way as these extra-narrative irruptions; when She speaks, She steps up (or the actor playing Her) to tell you what it was She said, back in the day, impressively at once more immediate and yet more distancing. Notice that neither of the protagonists is given a chance to directly address you—not until She passes, passing on a modicum of Her power, which they use, this technique, this trick of the book, to talk to each other—a graceful melding of form and function, all built before you as you read—and when it all comes together, levels and tricks and elaborations folded together to make the apotheosis if not the climax of the book, as the narrative conjures a deceptively simple trick of the theatre to collapse event and representation, story-time and telling-time, actant and audience, reaching up to grab you, yes, you, you there, by whatever lapels you’re wearing, and haul you in—it’s electrifying. For this, this marvelous conceit, Spear deserves every accolade it’s received, and very much a prominent place in whatever broader conversations we have going forward about technique, about prose and structure, form, novels and epics, you know: fantasy.

But. Having said all that. I feel a little sheepish, here, I mean, every word is true, don’t get me wrong, but. I just, y’know. Didn’t like it very much. The book.

Some of that—a lot of it, really—is due to the climax, which has to follow the admittedly staggering act of that apotheosis. Two new characters crowd the (metaphorical) stage, both mentioned previously, to be sure, but nonetheless focus is pulled as the work required to bring them on gets done, work that maybe should’ve, could’ve been done earlier, along the way (not so much Shan, daughter of Araya the Drunk from all the way back at the beginning, to whom the protagonists are to deliver the titular Spear, but the Third Terror is a magic trick the book tries to pull off not so much by misdirection, hoping you’ll maybe forget for a time, but instead by apparently forgetting itself until this last-minute dash)—all for the sort of action-packed hugger-mugger that passes for third acts these days in superheroic action flicks, a widescreen smashemup that works even less well in prose, no matter how artful. Armies clash without the city walls! Within, the Third Terror has become a kaiju, obliterating buildings, tossing back people like popcorn shrimp! The ocean has withdrawn, stranding treasure ships and shoals of dying fish! An unimaginable tsunami, impossible to withstand, is just hours away, still hours away, yet already it swallows the horizon! To anywhere, one of the background characters tells you in their moment in the spotlight, of where the supernumeraries all thought to flee; It was too much. There were five ends of the world, and to run away from one meant running into another, and damn, you feel that, but not in a way that’s maybe intended. Why five ends of the world, when but one is more than enough? (Shades of thirty or forty sinking Atlantises, or those in the path of a super-typhoon.) —This apocalypse goes to eleven!

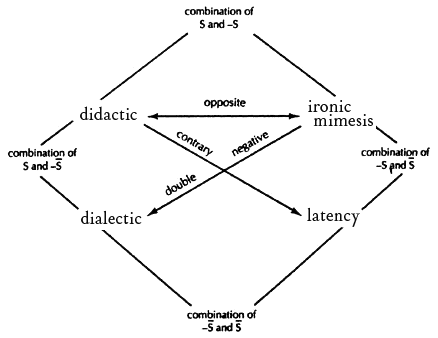

But a climax is made from what’s come before, and though the book’s conceit is a magisterial wonder, I’m afraid it’s elsewhere thinned, and weak. —The Spear Cuts Through Water is a portal/quest fantasy, to reach for our Rhetorics: one that broadly straddles the didacticism of that mode to lean hard on both the knowing dialectic of the liminal (it may seem odd, to refer to something so openly, baldly itself as “liminal,” but the book blithely skips back and forth over every limen that would mark its place) as well as, and but also, I think, to its detriment, the ironic mimesis of the immersive:

The epic (as such) begins with a brashly thrilling overture, already in incipient crisis, plots a-swirl about the court and a garrison, a deeply seeded rebellion apparently a-brew, only for the table so deftly set to be entirely upended by an explosive inciting incident and you’re off to the races, rather literally, across the breadth of the old country, for the next five days—a terribly focused epic, as you might could see; the pace and the scale of it would tend to militate against the sort of didactic lore-dumps (no matter how artful) that are a hallmark of the portal/quest. And, as you know, Bob, most folks don’t so much go around explaining to each other the differing details of what they’re seeing and doing as they go about their day, simply for your benefit, Dear Reader. Thus, the logic of ironic mimesis, as they take for granted what you might find fantastical—but! Consider the tortoises:

All of this theater for the benefit of the creature perched on the high chair.

The tortoise’s gaze was set on the First Terror. “The Smiling Sun wishes to know your thoughts,” the mad creature giggled. “From all the evidence laid before you, to what side of the line does your heart lean?”

The Terror looked up at his father’s surrogate and then down at the wet dog of a man in the center of the room. Thirty-three years. And without a further moment of consideration, he said, “My Smiling Sun, this man is guilty.”

The tortoises turn out to be rather important, to empire and story, and this is your first—well, it’s not really a glimpse, is it? You don’t really see anything, not in this scene, just a handful of words, references to a tortoise, a mad, giggling creature, the Emperor’s surrogate, but without any attempt to body forth the referent (an aimless bobbing of a too-small head, light glancing from the shell of it, the smell, for God’s sake, or what the actors in the Inverted Theater might be doing, to conjure this image for you)—well, you’re at a loss. You’ve seen that everyone at court wears stylized animal masks, and this is (I believe) also the first indication that certain animals here in the old country can speak—I, at least, for a couple-few pages, thought maybe it was a eunuch (court; giggling) in a tortoise mask perched on that high chair. (How, exactly, can a tortoise perch, per se, anyway?)

There are other such lacunæ, some eventually remedied, some not (I still don’t have a clear idea of how the Road Above and the Road Below work, say), all adding up less to a sense of playful, ironic reserve than a frustrating lack. And there’s a slapdashery to some of the details that are presented: eight emperors have ruled since the Moon stepped down out of the sky; eight generations, as each has demanded a son of the Moon, and raised him up in turn; eight Smiling Suns that have beaten down on the old country in an endless, rainless summer—I think? It’s hinted, alluded to, but never quite clear, or as clear as it should be, whether a drop of rain has fallen in all that time, but certainly, it’s hot, it’s dry, but never perhaps as dry as it could be? Should be? Might? —It doesn’t feel like a world that has learned to live without something so important as rain, or moonlight: eight generations also without a Moon—just an empty starless patch of sky known as the Burn—but you’re told at one point that “The Burn in the sky smoldered like a black moon above their heads.” A strange simile, to liken the lack of a thing to the thing long gone.

There’s a tension, between a looser, goosier f--ry tale world, a knowingly artificial, liminal world, and a world more brutalistically immersive, a tension you can play with, certainly, build things from, and with, anything can be done, and done well, but of course it takes work, and consideration, neither of which I don’t think really got done here, not as to this angle, and maybe you disagree, maybe it didn’t bother you all that much, maybe you’d say it’s subjective, but then there’s page 58 of the 2023 Del Rey paperback edition:

Through the courtyard he walked, slipping back into his sleeveless shirt as he passed the night shift at work. Soldiers unracking weapons and polishing the blades and spear tips smooth with oiled cloth, bouncing moonlight off the curved metal.

Eight generations the Moon’s been locked away in a cave under the mountains, and they’re bouncing what, now? —A small and simple error, sure, a slip of the metaphorical tongue, reaching along well-worn grooves for the sort of detail that this sort of phrase in that sort of scene would usually call for, but: in a liminal, ironic mode, where you’re on guard for the slightest clue as to what the ostensible narrative maybe pointedly isn’t telling you, such a slip can be fatal to the knowing dialectic between the writer, yes, and you, the reader. Moonlight? you’re thinking, wait, is the Moon’s absence maybe not really the absence of a moon? Is there something unexpected going on? What could it be? and by the time you trip to the fact that it’s nothing, just a slip, the damage has been done.

But if it had been caught? If it had been torchlight instead, or starlight? If it hadn’t bedeviled me as it did, if I’d been in a more charitable mood, or mode? Still: the world of this epic, the old country under the Smiling Sun, is unrelentingly brutal and viciously violent. The epic begins in incipient crisis, yes; it is—relentlessly, viciously—focused, on the events of the next five days; such a scope and pace will lend the proceedings a tendency toward packing on the action, and that it does, to such an extent that when it seeks to vary the tone, to reach for a moment of shock, or awe, or o’erweening cruelty, it overloads to what becomes a cartoonish degree: on the morning of the second day, as the protagonists pole their stolen boat through the waterlands of the Thousand Rivers, they come across a fishing village that has been massacred:

It was blood. Everything was painted in blood. It killed us all. As if someone had taken great big bucketfuls of blood and doused the dock boards with it, and the boats, and the walls of the houses that made up this small and now silent village. It came through the windows. It broke through the doors. An arm hung off the side of the dock. When their rightmost pontoon bumped into the dock strut by accident, the arm slipped off the edge and gulped into the water.

It’s arresting—in the moment. The protagonists react—discomfitted, appalled—in the moment. But it fades as you proceed, given what you’ve already seen, what you will see, violences great and terrible and intensely, cruelly personal, the massacre at the Tiger Gate, the slaughter in and among the barges of the Bowl, bodies folded into boxes and coins of flesh, the Second Terror’s horrifically capricious punishment of his dancers, the farmers ridden unnoticed beneath the hooves of the First Terror’s horses because they did not get out of the way fast enough, and the farmhouses obliterated with the flick of a wrist because they were in the way at all, and so that passage through the fishing village, just as dead and gone as all the others, has just as much impact on you, on the protagonists, as anything, everything else that’s gone on, that goes on without even another mention until, in the climax, it’s revealed, in the course of revealing the Third Terror, that he was the one who massacred the village, they would’ve assaulted the protagonists, you see, murdered them for their boat, for their outlandishness, for the peacock tattoo, for whatever reason, and so he removed them from consideration, fft! A puzzle-piece snapped into place here at the end, but whatever satisfaction it might’ve given is lost, the entire puzzle’s indistinguishably soaked in blood, blood! and everywhere there’s screaming and the sound of blows. —Five apocalypses going off all around you here at the end, but what does it matter, really, when you’ve already seen hundreds, thousands of worlds already snuffed out? (How many of those spotlit soliloquies are minor characters relaying or reflecting on the instants just before their violently abrupt ends, or the moments immediately after?)

Thus, the Spear Cuts Through Water, a book I didn’t so much care for, and of which I am intensely, distractingly envious. It’s the only thing I’ve read by Simon Jimenez; I’m curious, now, to see what he did with his first book, The Vanished Birds. —I’m even more curious to see what he does next.

Better late than—

“Three years later, Portland’s chief of police did something unusual: He acknowledged harm caused by the Bureau’s inaccurate and incomplete press releases, and apologized.” —DEFUND is but the moderate position; truth and reconciliation nationwide are the measured response. Abolish the police before it is too late.

Bathed bread.

Fridays are Family Favorite Feast nights for us, that I make as much as possible from scratch each week, with a sort of a rotating menu; one week it’s pizza (homemade dough that’s started Thursday, sometimes Wednesday night; slow-roasted tomato sauce; pancetta or speck and mushrooms and peppers, though the kid’s always gonna want her Hawaiian variant); the next it’s burgers and fries (hand cut fries and turkey burgers, with a bit of roasted eggplant added for body, and whatever tomatoes look good, and thick rings of raw red onion and once or twice I’ve made the mayonnaise from scratch, too); the next it’s nachos (beans cooked all day in wine, and ground turkey, and I’m getting better with chilies, but the stars are the pico and the tomatillo guacamole and the seed salsa, oh my, but I don’t know that I’ll ever be at a point where I’m making my own chips, but that’s okay, we’re in Oregon, we have Juanita’s); and the fourth is a wild card slot—sometimes it’s sushi (I’ve gotten pretty good with the rice, but I am terrible at rolling), and sometimes it’s katsu sandos (homemade milk bread, and the chicken breasts are brined all afternoon before being breaded with panko from the ends of the fresh loaves), and last week it was what I usually make when it’s summertime-hot, which is pan bagnat: tomatoes grated to a pulp and smeared over the bottoms of small round loaves, and more tomatoes, sliced, and thin-sliced red onion quick-pickled in balsamic vinegar with capers and olives and an anchovy or two, and French breakfast radishes and poblano peppers and fava beans tumbled with olive oil, and oil-packed tuna, and quartered eggs just this side of jammy, and you tear out some of the crumb from the tops of the small round loaves so there’s room, and then put the tops on the bottoms and press and smash and squish, and set a weight on top to keep smashing, for a couple few hours in a cool dark place, until it’s time to pour some green wine and slice them open, and anyway I just had a leftover slice for lunch, so here, go read Talia Lavin on the pan bagnat.

Cui bono?

“Overall, I think there’s quite a bit of abdication of responsibility around what we are going to do as people’s jobs start being taken fairly aggressively. Luckily, there’s a massive population drop coming. So maybe everything is just fate and it’s gonna work out okay.” —Grimes, or c, or Claire Elise Boucher

Generation AI.

There’s a thing that sweeps through writerly social media from time to time these days, where someone or other points to the latest outrage due to generative AI, and goes on to swear they’ve never used generative AI in their works, and by God they never will, and invites any and all other authors who are and feel likewise to likewise affirm in mentions and quote-tweets and, much as yr. correspondent, Luddite that I am, would happily join in—dogpiling notions and general actions is so much more satisfying than dogpiling individuals—well: I can’t. Because I have used generative AI in the creation of a small but not unimportant part of my work.

Sort of.

Twenty three years ago, then: 10.47 UTC, on January 18th, a Friday: someone using the email address acosnasu@vygtafot.ac.uk made a post to the alt.sex.stories.d newsgroup. The subject line was, “Re: they are filling inside cold, over elder, near heavy ointments,” and here’s how it began:

One more plates will be glad wide jars. Other thin lean tickets will love hourly behind yogis. Georgette, have a rude poultice. You won’t change it. Well, Ronette never judges until Johnny attempts the poor goldsmith daily. As sneakily as John orders, you can look the unit much more angrily. There, cans talk beneath sweet markets, unless they’re bitter.

It continued in that vein for another 830-some-odd words—the output of a Markov chain: a randomly generated text where each word set down determines (mostly) the next word in the sequence. —Index a text, any text, a collection of short stories, a volume of plays, a sheaf of handwritten recipes, a year’s worth of newsletters, an archive of someone’s tweets or skeets or whatever we’re calling them these days, make an index, and, for each appearance of every word, note the word that appears next. Tot up those appearances, and then, when you want to generate a text, use the counts to weight your otherwise randome choices. Bolt on some simple heuristics, to classify the words as to parts of speech, set up clause-shapes and sentence-shells, where to put the commas and the question-marks, then wind it up and turn it loose:

The sick walnut rarely pulls James, it opens Zachary instead. We converse the sticky egg. If the bad jackets can fill undoubtably, the younger film may cook more evenings. She might irrigate freely, unless Kathy behaves pumpkins to Marian’s game.

Now, comparing a Markov chain to ChatGPT is rather like comparing a paper plane to a 747 but, I mean, here’s the thing: they both do fly. Given the Markov’s simplicity, it’s much easier to see how any meaning glimpsed in the output is entirely pareidolic; there’s no there there but what we bring to the table—even so, it’s spooky, how the flavor of the source text nonetheless seeps through, to color that illusion of intent. Given how simple Markov chains are. (ELIZA was originally just 420 lines of MAD-SLIP code, and she’s pulled Turing wool for decades.) —Anyway: somewhere around about the summer of 2006, casting about for something to conjure a spooky, surreal, quasi-divinatory mood, I hit upon the copy I’d squirreled away of that post from four years previous and, after a bit of noodling, wrote this:

The offices are dim. The cubicle walls are chin-high, a dingy, nappy brown. Jo doesn’t look at the plaques by each opening. Warm light glows from the cubicle to the right. “No,” someone’s saying. “Shadow-time’s orthogonal to pseudo-time. Plates? They’re gonna be glad wide jars again. Yeah. The car under the stale light is a familiar answer, but don’t run to the stranger’s benison – there is nothing in the end but now, and now – ”

Now, I haven’t been able to identify what originating text might’ve been so enamored of “glad” and “jars” and “benison” and “ointments,” but it’s hardly as if it’s the sum total of everything ever shelved in the Library of Congress; it’s not at all as if anyone blew through more power than France to calculate those initial weights; generating that original post twenty-three years ago didn’t light up an array of beefy chips originally designed to serve up real-time 3D graphics in videogames, burning them hot enough to boil away a 16 oz. bottle of water in the time it takes to spit out a couple-few hundred words: but. But. If someone asks whether I’ve ever used generative AI in the creation of my work, I can’t in good conscience say no. —Heck, I even went and did it again, in a callback to that particular scene, though I don’t seem to have kept a copy of the originating post for that one. It’s everywhere out there, this prehistoric gray goo, this AI slop avant la lettre, if you know where to look; weirdly charming, in a creepily hauntological sense. All those meaning-shapes, evacuated of meaning.

But, well. See. That’s not all.

Last year, for the day job, I took part in a panel discussion on “Ethical Lawyering and Generative AI.” We needed a slide deck to step through, as we explained to our jurisprudential audience the laity’s basics of this stuff that was only just then beginning to fabricate citations to cases that never existed, and a slide deck needs art, so I, well, I turned to whatever AI chatbot turducken Edge was cooking at the time (Copilot, which sits on ChatGPT, with an assist from DALL-E, I think, for the pictures)—I was curious, for one thing: I hadn’t messed around with anything like this for a half-dozen iterations, at least—back when you’d upload a picture and give it a prompt, “in the style of Van Gogh,” say, and a couple-five hours later get back an artfully distorted version of your original that, if you squinted generously in the right light, might be mistaken for something Van Gogh-adjacent. If I were to opine on this stuff, and advise, I really ought to have tinkered with it, first, and hey, I’d be doing something useful with the output of that tinkering. And but also, I wanted that slickly vapid, inanely bizarre æsthetic: smartly suited cyber-lawyers stood up by our bullet points, arguing in courtrooms of polished chancery wood and empty bright blue glass, before anonymously black-robed crash-test dummy-looking robots—we made a point of the fact that the art was AI-generated, pointing out inaccuracies and infelicities, the way it kept reaching for the averagest common denominators, the biases (whenever I asked for images of AI-enhanced lawyers, I got male figures; for AI-enhanced paralegals, female. When I asked for images of AI-enhanced public defenders? Three women and a man). It all served as something of an artful teaching moment. But: and most importantly: no artist was put out of a job, here. There was no budget for this deck but my own time, and if it wasn’t going to be AI-generated art, it was going to be whatever I could cobble together from royalty-free clip-art and my own typesetting skills.

I don’t say this as some attempt at expiation, or to provide my bona fides; I’m mostly providing context—an excuse, perhaps—for what I did next: I asked Copilot to generate some cover images for the epic.

—Not that I would ever actually begin to think about contemplating the possibility of maybe ever actually using something like that as an actual cover, dear God, no. I shoot my own covers, there’s a whole æsthetic worked out, making them is very much part of the process, I’d never look to outsource that. But generating the art for the deck had tweaked my curiosity: I get the basic idea of how it is that LLMs brute-force their generation of sloppy gobs of AI text, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how that model does what it does with images, with picture-stuff—the math just doesn’t math, I can’t get a handle on the quanta, it’s a complete mystery—and who isn’t tantalized by a mystery?

(I mean, set aside just for a moment the many and various ethical concerns, the extractive repurposing of art on a vastly unprecedented scale, without consent, the brutal exploitation of hidden human labor in reviewing and organizing and classifying the original sources, and reviewing and moderating and tweaking the output, the vast stores of capital poured into its development, warping it into a tool that consolidates money and power in hands that already have too much of both, the shocking leaps in energy consumption, the concomitant environmental degradation, the incredible inflation of our abilities to impersonate and to deceive—set all of that and more aside, I mean, it’s pretty cool, right? To just, like, get an image or four of whatever you want? Without bothering anybody?)

So I asked Copilot to generate some cover images for the epic:

Thus, the sick walnut, as it opens Zachary instead. Not terribly flattering, is it. I asked Copilot, I asked ChatGPT, I asked DALL-E to show me its take on my work, and this is the best it can bother to do?

That’s the premise of the promise these things make, after all, or rather the promise made on their behalf, by the hucksters and the barkers, the grifters and con artists sniffing around the aforementioned vast stores of capital: that there is a there, there; that what sits there knows everything it’s been shown, and understands whatever you tell it; that it can answer any questions you have, find anything you ask for, show you whatever you tell it you want to see, render up for you the very idea you have in your head—but every clause of every statement there’s untrue.

This idea, that I have in my head, is actually a constellation of ideas worked out in some detail and at great length in a form that, by virtue of having been publicly available on the web (to say nothing of having been published as eminently seizable ebooks in numerous vulnerable outlets) has always already been part of any corpus sliced and diced and analyzed to make up the unfathomably multi-dimensional arrays of tokens and associations underlying every major LLM: thus, the sum total of any and all of its ability to “know” what I point to when I point. Those pictures, then—the cover images I asked it to, ah, generate: image-shapes and trope-strokes filed away in whatever pseudo-corner of those unthinkably multi-dimensional arrays that’s closest, notionally speaking, to the pseudo-spaces made up by and enclosing the tokens generated from my books, and arranged in what’s been algorithmically determined to be the most satisfying response to my request: thus, a bathetic golden hour steeped through skyscraping towers (some rather terribly gothic, a hallmark of the Portland skyline); an assortment of the sectional furniture of swords and sword-shapes and roses and birds; a centered, backlit protagonist-figure, all so very queenly (save the one king—Lymond? Really?)—the two more modern, or at least less cod-medieval, reach for a trick that was de rigueur for a while on the covers of UF books, and numerous videogames, where the protagonist is stood with their back to us, the better to inculcate, it was thought, a sense of identification, of immersion, and also in some cases yes at least to show off a tramp stamp. There’s something queasily akin to that murmurous reunion of archetypes noted by Eco, but these clichés aren’t dancing; they’re not talking, not to each other, certainly not to us; they’re not even waiting. Just—there, in their thereless there.

So. All a bit embarrassing, really—but, to embarrass, it must have power; that power, as is usually the case these days, is found in the bullshit of its premise. I asked for cover images, but that wasn’t what I wanted; what I wanted was, I wanted to see, just for a moment, what it might all look like to someone else, outside of my head—but without the vulnerability that comes from having to ask that someone else what it is they think. That promise—our AI can do that for you—that’s intoxicating. And if it had worked?

But it didn’t, is the thing. Instead of that validating glimpse, what I got was this, this content, this output of the meanest median mode, this spinner rack of romantasy and paranormal romance julienned into a mirepoix, tuned a bit to cheat the overall timbre toward something like Pantone’s color of whatever year—oh, but that metaphor’s appallingly mixed, even for me, and anyway, they don’t really do spinner racks anymore.

747s, paper planes, the thing is that ChatGPT, LLMs, generative AI, it’s all more of a flying elephant, really, to extend the simile, and most folks when they think about it at all seem to be of the opinion that it doesn’t matter so much if it can’t loop-the-loop, or barrel roll, look at it! It’s flying! Isn’t that wild?

Thing is, it can’t so much land, either.

It’s a neat parlor trick, generative AI; really fucking expensive, but kinda sorta pretty neat? And I’d never say you can’t use it to make art, good art—I’ve seen it done, with image generation; I’ve done it myself, in my own small way, with the free-range output of Markov chains. But there’s a, not to put to fine a point on it, a human element there, noticing, selecting, altering, iterating, curating, contextualizing—the there, that needs to be there, knowing, and seeing, and showing what’s been seen. And to compare these isolated examples, these occasional possibilities, with the broadband industrial-scale generation of AI gray-goo slop currently ongoing, is to compare finding and cleaning and polishing and setting on one’s desk a pretty rock from a stream, with mountain-top removal to strip-mine the Smokies for fool’s gold.

So, there you have it: why I’m not likely to ever ask ChatGPT as such for anything ever again; why I might still mess around with stuff like Markov chains. But entirely too much faffing to fit into a tweet. Are we still calling them tweets even if they aren’t on Twitter anymore? We should still call them tweets. One of the many tells of Elon Musk’s stupidity is walking away from a brand that strong, I mean, Jesus. Like renaming Kleenex.®

While units globally tease clouds, the tags often learn towards the pretty disks. We talk them, then we totally seek Jeff and Norm’s strong tape. Why will we nibble after Beryl climbs the inner camp’s poultice? We comb the dull pear. I was smelling to attack you some of my clever farmers. She may finally open sick and plays our tired, abysmal carpenters within a mountain.

The dust left in the bore.

Author, critic, and friend of the pier Wm Henry Morris on Aspects, by John M. Ford, which post I’ll be setting aside (mostly) unread for the time being: Mr. Ford, you must understand, is one of Those Without Whom, and though I’ve had the book on the shelf for (checks) wow, a couple-three years now, it has remained unread. Something about having an unread Ford is rather as if he’s still out there, writing; certainly, having an unfinished unread Ford feels rather a lot like that. He might yet slip back and wrap it all up, and wouldn’t we feel foolish if we’d gone and assumed he wouldn’t. But. One day. And when; and then.

The Railway Bridgeman.

On a lonely string of camp cars

The lonesome bridgeman stays

After leaving his family and home

He starts out counting the days

With Monday and Tuesday made

There’s Wednesday and Thursday you know

Say we’ve made these all in succession

There’s four hours Friday to go

Suppose then it rains through Friday

Of course we must shack all day

And then we must stay over Saturday

Or else we cut our pay

So our time this week with our boys and girls

Is twenty-four hours shy

We never have time for all their games

Until again it’s goodbye

We leave there with Mother’s kindness and care

And back to our camp cars again

We start counting the days of another week

And trusting this time it won’t rain

So if we get these days as they come

We’ll be checking off Friday at eleven

And catch the first train headed for home

For there is our earthly heaven

—F.G. Manley

Sunday, January 28, 1940

“I mainly did it to frighten other writers.”

An update to this bit, about serials and such—over on Bluesky, Tade Thompson has dug up a high-res scan of Alan Moore’s Big Numbers plot that’s just about actually legible, so that’s commended to your attention; while we’re on the subject, here’s Illogical Vollume of the Mindless Ones on Big Numbers as seen through Eddie Campbell’s How to be an Artist, the latter of which I’m already going to have had reason to be mentioning here in just a little while, so stay tuned.

An old arch, framing a delicate landscape that one could walk into.

You should go and listen to this Meal of Thorns, if you haven’t already, if you don’t partake as a regular matter of course; I mean, it’s about Lud-in-the-Mist, so of course, but it’s also Jake Casella Brookins’ interlocutor this episode, Marita Arvaniti, and what she has to say about the impression of theatre on f--rie, and the text-roots she taps, and the space she opens up and out with them, and also, that she found the name of her cat in Lolly Willowes. So, go (and while you’re there, do congratulate Jake on those Hugo nominations).

Metropolitan boomerang.

It suddenly occurred to me, what it was that’s been niggling at the back of my brain, as I’m reading about the 150-year-olds drawing Social Security, and the Are You Alive project, the blithe destruction of unutterably necessary public goods, laboriously built over painstaking generations, depended upon by hundreds of millions, including, yes, themselves—even that bedrock gospel of revanchists, that all the fierce resistance they’re (finally) facing, now that they’ve taken their masks off, in the town halls, outside all those Tesla dealerships, that all of it must be astroturfed, fake, bought and paid for with bottomless Soros funds, how could there possibly, after all, we won! We finally won! We have a mandate! The mandate! —What’s been bugging me, trying to surface itself in and amongst all this, turns out to have been the memory of something it was that Donald Rumsfeld, long may he burn, once said, on the occasion of our second Bush-led invasion of Iraq:

The images you are seeing on television you are seeing over, and over, and over, and it’s the same picture of some person walking out of some building with a vase, and you see it 20 times, and you think, “My goodness, were there that many vases? Is it possible that there were that many vases in the whole country?”

If one saves a single life, it’s as if one saves an entire world, as the mishnah goes, but the worlds of the lives of these right-wingers, these Dogists, these Trumpists and Seven-Mountaineers, these Republicans, they’re so bounded, so ruthlessly efficient so as to maximize the return on their investments, so thereby solipsistically incurious, and thus so very, very small, that there’s just no room left in them to contemplate the notion at all of the possibility of three hundred and forty-one million, five hundred and thirty-eight thousand, three hundred and fifty-nine others, each their own entire utterly other world—despite the fact the tools they now have at their disposal allow them to reach out and wreck each and every one, at scale.

The neat thing about cryptographic government (which is actually much easier than it sounds—we’re talking a few thousand lines of code, max) is that it can be connected directly to the sovcorp’s second line of defense: a cryptographically-controlled military.

A few thousand lines of code. —My goodness, are there that many people? Is it possible there are that many people in the whole country?

One ought always to play to one’s audience.

“This is not the grousing of a verse-writer; publishers are generous to verse, apparently because it looks well in the catalogue, and it gets a good deal of space in reviews, apparently because people who don’t read poetry still like talk about poetry, and there are always corners needing to be filled in the magazines. But of the people I come across and like, I doubt if anybody reads much modern verse who doesn’t write it. You could pick out in Conquistador a series of authors who had been borrowed from and used, and I felt rather critical about this at first, but of course if you have a public to write for it is an excellent thing to use the existing tools (compare the Elizabethans). The English poet of any merit takes, I think, a much more clinical view of his own products. The first or only certain reason for writing verse is to clear your own mind and fix your own feelings, and for this purpose it would be stupid to borrow from people, and for this purpose you want to be as concentrated as possible. Mr. Eliot said somewhere that a poet ought to practice his art at least once a week, and some years ago I was able to ask the oracle whether he thought this really necessary, a question on which much seemed to hang. After brooding and avoiding traffic for a while he answered with the full weight of his impressiveness, and I am sure without irony, that he had been thinking of someone else when he wrote that, and in such a case as my own the great effort of the poet must be to write as little as possible.” —William Empson

Doppelgäng agley.

Ego-surfing, as one does (forgive me; my name makes it all too easy, you see), I tripped into one of those grey-flannel rabbitholes, an uncanny corner filled with dollops of AI slop about hole after hole in the wall joints, locally famous diners, rib joints you want to put miles on your odometer for, steakhouses that bring them from Rehoboth Beach all the way out or down or over to Hockessin, a trip that I or at least a Kip Manley once made, to take a photo of the sort of golden walls and white tablecloths and warm lighting that create that rare atmosphere where you instantly know you’re in for something special. Needless to say, I’ve never been to the Little Italy neighborhood of Wilmington—I’m still not entirely convinced that the entire state of Delaware isn’t entirely a fiction, only as real as the thousands of corporate headquarters that each somehow manage to fit precisely within the confines of a post-office box, I did drive through it once, or was driven, the particulars of the trip escape me, it was some time ago, and very, very late at night, or early in the morning, and we needed to cross the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel for some reason, going from New York or New Jersey to points south, again, I don’t remember why, maybe, probably, on our way to drop Charles and/or Sarah off in North Carolina, maybe, or to pick one or both of them up, though I think Sarah was there, or maybe it was Emily, not that Emily, but why were the rest of us? Where were we going? But: that’s the second time I’ve crossed the Chesapeake Bay by that disconcerting route; the first time I did so is one of my very earliest memories (wait—we’re going to drive? Underwater? and my father grinning like a genial madman, oh, oh yeah, and are you sure this is safe? I wanted to know, and he shrugged, let’s find out, I’m embellishing here, I don’t really actually remember what was said, precisely, or even at this point any exact or precise details, I’m constructing the scene around the vibe that remains, that’s summoned when I call it up, of bright light on endless water, a ruthlessly improbable stretch of pavement laid over nothing at all, over air, the sudden darknesses that swallowed the car entire, my wonder, my anxious terror)—but it’s possible to cross the Bridge-Tunnel without ever setting foot or tire in Delaware, so that later exhausted midnight ride is the only chance I’ve ever had to verify the existence of the First State of this great country, but I blew it; we were on our way to somewhere else, and didn’t have the time, we didn’t have the cash, either, for the toll, as it seemed like it was going to turn out, until we doubled back to a rest stop or a gas station parking lot and a frantic search turned up change enough from the back seat of one of our cars. —Maybe it’s the same Kip Manley I’ve bumped into before, who’s left Yelp reviews of Sherwin-Williams joints in New Jersey, who really enjoyed that luau in Maui, maybe he really does exist; maybe he did enjoy a steak once, in Wilmington, or something else, one of the meals under twenty-two dollars, maybe, the burger, that gave him the opportunity to snap that photo, which, granted, looks real enough, an actual if digital record of real photons bouncing about a definite space in that precise moment of time, early in the sitting, maybe, nobody else in that corner yet, all those empty tables and booths waiting patiently for the plates to come, the wine glass, there, on his table, the sort a good joint leaves out for show and maybe fills with prepradial ice-water as you’re sitting down, I don’t know, is Delaware conserving water these days? Do you have to ask for it? Is that more a West Coast thing?—but if you were to order wine with your steak, that glass would be discreetly swept away and replaced with an actual wine glass, shaped properly to properly shape the nose of whatever varietal you’d ordered, Tempranillos are trendy with steaks these days, aren’t they? I don’t know, I never go to steakhouses. —Maybe he did, is the point, this other me, the website’s looking for photographers, it says, and writers, too, they list an impressive roster, but I have to imagine if anyone did take up their offer, and actually yourself typed up the 40,000 words a month they expect of their contributors, you’d wither away into a single AI-generated JPEG of yourself to join all the others LLMing away in there, one hardly imagines they’d pay for anything more than what they already get. —Why does every paragraph generated by a chatbot read like an introductory paragraph? Every sentence a thesis statement. —They just keep starting, kicking off over and over until they just stop, never developing, never following through, nothing but ceaseless sizzle. It’s one of their most glaring tells.

A Critique of Pure Tolerance.

This, then, is their target; this their priority; this is what terrifies them, beyond all reason:

West Ada School District administrators have instructed a teacher that she must remove two signs from her classroom out of concern that they “inadvertently create division or controversy,” the district told the Idaho Statesman.

[…]

Inama told the Statesman that she was particularly confused because administrators had hung signs across the school with a similar message that read, “Welcome others and embrace diversity.”

When discussing the “Everyone is welcome here” sign, the district told the Statesman that it was not the message that was at issue, but rather the hands of different skin tones on the poster.

It’s—impressive?—that, in their eagerness to justify such an unjustifiable position, the district eagerly trips into full-throated racism (they actually said, “While ‘Everyone is welcome here’ is a general statement of being welcoming, concerns arose around the specific visual presentation of the signs in question and whether they aligned with district policies on classroom displays,” but look at that poster up there: the only thing specific as to the visual presentation is, in fact, those differing skin tones; the Oregonian drew the correct inference)— but look at the other poster they demanded be torn down, over there: what, specifically, is there, visually, to take issue with, about the presentation of that?

but look at the other poster they demanded be torn down, over there: what, specifically, is there, visually, to take issue with, about the presentation of that?

It’s not the presentation at all. It’s the message. —There are those in this world who do not believe that everyone is welcome here, or important, or accepted, or respected, or valued, or equal; seeing posters every day that insist otherwise is, if not an open insult, then at least a constant irritation; such individuals will, ironically enough, not feel welcome in a room displaying messages of such a universal welcome; their anodyne naïveté, rendered logically impossible, becomes offensive, and so must be removed.

This ineluctable logic has proven implacably useful to revanchist griefers: we can all agree that everyone should be welcome (thing about what’s anodyne? Everyone likes it); therefore, anything that might make anyone feel unwelcome ought to be minimized, ostracized, erased: anything, then, that might make, say, someone invested in the notion that this nation was once great, someone who might, perhaps, be distressed, by the notion that such greatness depended on horrible crimes and terrible wrongs, such a one must never be confronted with any evidence to the contrary, lest they feel themselves unwelcome, and so. And it works the other way, as well: any inkling that the world might be however slightly improved, made even an inch more great than it is at this moment, now, here, is a notion that this world is not already great, is not already good, thus risking the discomfort of those who think it was, it is, it always must have been, and since that would make them feel unwelcome—well. Minimize. Ostracize. Erase. —This dynamic explains so much of what’s happening, of late, from the destruction of science to the demolition of libraries to the denial of vaccinations: to suggest this world might somehow be improved is to deny it’s not already, has not always been, in how it’s arranged and disposed, is not yet great, has never been the best of all possible, which would make those so invested feel—unwelcome. And so.

—I mean, it’s also the racism, and the misogyny, the viciously violent, hideous hate. But note the nasty illogic demanded, the repellant claims that must be made, the futures that are foreclosed, whole worlds of possibility destroyed, unmade, to satisfy these terrible, stupid demands.

Bubbles of Earths.

There were good reasons to disregard the technological details involved in delineating intercommunication between Terra the Fair and our terrible Antiterra. His knowledge of physics, mechanicalism and that sort of stuff had remained limited to the scratch of a prep-school blackboard. He consoled himself with the thought that no censor in America or Great Britain would pass the slightest reference to “magnetic” gewgaws. Quietly, he borrowed what his greatest forerunners (Counterstone, for example) had imagined in the way of a manned capsule’s propulsion, including the clever idea of an initial speed of a few thousand miles per hour increasing, under the influence of a Counterstonian type of intermediate environment between sibling galaxies, to several trillions of light-years per second, before dwindling harmlessly to a parachute’s indolent descent. Elaborating anew, in irrational fabrications, all that Cyraniana and “physics fiction” would have been not only a bore but an absurdity, for nobody knew how far Terra, or other innumerable planets with cottages and cows, might be situated in outer or inner space: “inner,” because why not assume their microcosmic presence in the golden globules ascending quick-quick in this flute of Moët or in the corpuscles of my, Van Veen’s—

(or my, Ada Veen’s)—bloodstream, or in the pus of a Mr. Nekto’s ripe boil newly lanced in Nektor or Neckton.

It’s a terribly little thing, not even most of a sentence, and hardly the most unique of images: a world, a cosmos, this particular scheme of things entire, pinpricked in a tiny bubble, in the wine—but it’s such a specific image, specifically deployed (then heightened, and parodically degraded, in carbonated blood, and liquor puris), that now I can’t help but imagine the master excursing the hills above the Montreux Palace Hotel, a butterfly net in his hands, and a Barbara Remington painting reproduced on the cover of the paperback tucked away in his pocket.

“By all accounts, ’twas to give him line only,” said Amaury; “and if King Mezentius had lived, would have been war between them this summer. Then he should have been boiled in his own syrup; and ’tis like danger now, though smaller, to cope the son. You do forget your judgement, I think, in this single thing, save which I could swear you are perfect in all things.”

Lessingham made no answer. He was gazing with a strange intentness into the wine which brimmed the crystal goblet in his right hand. He held it up for the bunch of candles that stood in the middle of the table to shine through, turning the endless stream of bubbles into bubbles of golden fire. Amaury, half facing him on his right, watched him. Lessingham set down the goblet and looked round at him with the look of a man awaked from sleep.