Disposable.

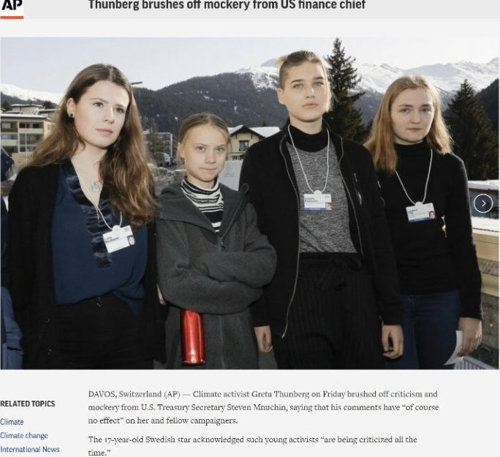

Before (the picture upon being taken):

After (the picture upon being published):

There was no ill intent. AP routinely publishes photos as they come in and when we received additional images from the field, we updated the story. AP has published a number of images of Vanessa Nakate.

Subsequently (the picture anent the explanation):

We regret publishing a photo this morning that cropped out Ugandan climate activist Vanessa Nakate, the only person of color in the photo. As a news organization, we care deeply about accurately representing the world that we cover. We train our journalists to be sensitive to issues of inclusion and omission. We have spoken internally with our journalists and we will learn from this error in judgment.

The subsequent more-of-an apology:

Vanessa, on behalf of the AP, I want to say how sorry I am that we cropped that photo and removed you from it. It was a mistake that we realize silenced your voice, and we apologize. We will all work hard to learn from this. Sincerely, Sally Buzbee

— Sally Buzbee (@SallyBuzbee) January 26, 2020

David Ake, the AP’s director of photography, told Buzzfeed UK that, under tight deadline, the photographer “cropped it purely on composition grounds.”

“He thought the building in the background was distracting,” Ake said.

reformacons, blood-and-soilers, curious liberal nationalists, “Austrians,” repentant neocons, evangelical Christians, corporate raiders, cattle ranchers, Silicon Valley dissidents, Buckleyites, Straussians, Orthodox Jews, Catholics, Mormons, Tories—

“It did all raise a question. What if Trump had dialed down the white nationalism after taking the White House and, instead of betraying nearly every word of his campaign rhetoric of economic populism, had ruthlessly enacted populist policies, passing gargantuan infrastructure bills, shredding NAFTA instead of remodeling it, giving a tax cut to the lower middle class instead of the rich, and conspiring to raise the wages of American workers? It doesn’t take much to imagine how that would play against a Democratic challenger with McKINSEY or HARVARD LAW SCHOOL imprinted on his or her forehead. There seemed to be two futures for Trumpism as a distinctive strain of populism: one in which the last reserves of white identity politics were mined until the cave collapsed and one in which the coalition was expanded to include working Americans, enlisting blacks and Hispanics and Asians in the cause of conquering the condescending citadels of Wokistan. Was it predestined that Trump would choose the former? Steve Bannon was already audience-testing Trumpism 2.0, wrong-footing the crowd at the Oxford Union with complaints about the lack of black technicians in Silicon Valley. Why couldn’t Trumpism go in this direction in reality? The shrewdest move for the NatCons would surely have been to attract as many non-whites as possible to the Ritz and strike fear into the hearts of the globalists with a multiracial populist carnival—a new post-Trump pan-ethnic coalition that would someday consider it quaint that it had once needed to begin conferences with the profession: We are not actually racist.” —Thomas Meaney

A better solution to the problem.

“Firefighters’ calendar featuring Portland homeless camps” is one hell of a 2020 mood.

Fire officials haven’t identified the firefighter who made the calendar. It surfaced at Portland Fire Station No. 7, one of the city’s busiest stations in the Mill Park neighborhood at 1500 SE 122nd Ave., and firefighters from other stations apparently expressed interest in having one of their own, according to Fire Bureau members. Twenty-four firefighters are assigned to Station 7.

It case it’s not clear from the jump, the calendar wasn’t laudatory.

Alan Ferschweiler, president of the Portland Fire Fighters Association, said the calendar, while insensitive, highlights greater problems that aren’t getting enough attention from city leaders: “the friction between firefighters and the houseless population” and an “overstressed work force.”

Firefighters, he said, usually are sent to deal with low-level medical calls at homeless camps or to put out fires at the camps. Because Portland police aren’t responding as often to these calls, firefighters often feel unsafe or face aggression from people who are abusing drugs or alcohol, Ferschweiler said.

“Those negative interactions have a resounding effect on our members,” he said. “Police have responded less and less and less to those calls with us. That’s part of the situation too. I feel there’s calls where I wish the cops were here.”

Of course, there are very good reasons to keep interactions between the Portland Police Bureau and the houseless population at a minimum.

And one might be thankful it’s paramedics showing up for medical emergencies, and firefighters for fires, and not armed police, and one may lament that our first responders must so often respond firstly to situations and circumstances for which there is no clear-cut training, with resolutions far beyond the immediate scope of their admirably focused powers, but one can also take note of the curious rhetorical figure in Ferschweiler’s statement, “the friction between firefighters and the houseless population,” which whisks us with breathtaking suddenness to some notional arena where two unitary sets of stakeholders, firefighters and the houseless population, might set their competing agendas to duking it out with, sadly, some little friction.

—It’s understandable, to be charitable, that one would be so despondent at the abjunct between what one is tasked with doing or even what one can do at all, and what must needs be done, that one turns one’s efforts to what one can reach, metonymically speaking; thus does fighting homelessness become fighting the houseless population, much as what happened with the war on drugs. —And one could be so horrified by the idea of one’s own precarity that one might choose to assert one’s security by insisting such horrors happen only to a certain certain sort, you know, the houseless population, those people, THEM—look, there they are now, over there, not me, nope, nossir! —But such seductive turns of thought however understandable turn in your hand, lead you astray, make you think you’ve grabbed hold of something that isn’t there at all:

“Let’s have some talk about the problem we’re having,” he said.

A stranger’s stabbing Saturday night of an off-duty fire lieutenant who was at a Portland bar celebrating his wedding anniversary further highlights the problem, the union president said.

And surely we all can agree no matter how figurative our rhetoric that to see this incident as a skirmish in the “friction” between firefighters and the houseless population (McClendon, the estranged “stranger” who stabbed above, has no fixed address)—that would be dizzyingly unhinged. Yet here we are, at the end of our discussion, wrapping it up with this, as if it says anything at all about a Fire & Rescue station, frustrated by friction, letting off steam through the “dark humor” of a calendar that mocks homeless camps.

“We want to have a better solution to the problem,” Ferschweiler said. “We want people like Paul to be able to come downtown, have a good time with his wife and be able to go home safely.”

The borders of US and THEM, downtown and safety, are easy enough to sketch with a map like that. —Myself, I want people like Debbie Ann Beaver to be able to take the medicine they need in peace. This friction kills.

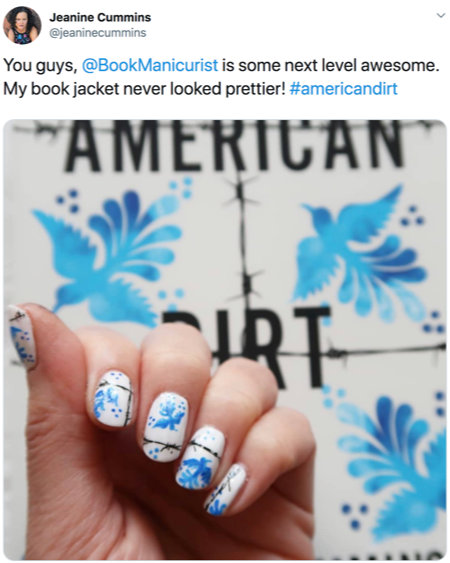

Painstakingly æstheticized chisme.

“After a few days,” says Myriam Gurba, “an editor responded. She wrote that though my takedown of American Dirt was ‘spectacular,’ I lacked the fame to pen something so ‘negative’.” Let’s make sure she has fame enough to pen as negative as she wants in the future. —Some additional background on Oprah’s latest bookclub pick. Remember, kids: the fail condition of condemnation is reification!

Quinnipiac in retrograde.

“But received wisdom about electability is powerful precisely because it defies reason and is resistant to critical scrutiny. Like many of the other concepts that shape electoral punditry and political discourse—charisma, qualification, momentum, authenticity—electability is a shibboleth of a political mysticism that ‘tickles the brain’ only because it cannot fully engage it—a drab, gray astrology, maintained by over-caffeinated men.” —Osita Nwanevu

On the one hand; on the other.

From the opinion filed today in Juliana v. United States, 6:15-cv-01517-AA, reversing the certified orders of the district court and remanding the case with instructions to dismiss for lack of Article III standing:

Contrary to the dissent, we do not “throw up [our] hands” by concluding that the plaintiffs’ claims are nonjusticiable. Diss. at 33. Rather, we recognize that “Article III protects liberty not only through its role in implementing the separation of powers, but also by specifying the defining characteristics of Article III judges.” Stern v. Marshall, 564 U.S. 462, 483 (2011). Not every problem posing a threat—even a clear and present danger—to the American Experiment can be solved by federal judges. As Judge Cardozo once aptly warned, a judicial commission does not confer the power of “a knight-errant, roaming at will in pursuit of his own ideal of beauty or of goodness;” rather, we are bound “to exercise a discretion informed by tradition, methodized by analogy, disciplined by system.” Benjamin N. Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process 141 (1921).

From the dissent:

Seeking to quash this suit, the government bluntly insists that it has the absolute and unreviewable power to destroy the Nation.

Freeze, peach!

How poetically telling, that the concept of kettling disruptive elements away in a First Amendment zone has been extended from protestors to reporters.

Message: I care.

The peculiar fusion of public and private, market forces and administrative oversight, the world of hallmarks, benchmarks, and stakeholders that characterizes what I’ve been calling centrism is a direct expression of the sensibilities of the professional-managerial classes. To them alone, it makes a certain sort of sense. But they had become the base of the center-left, and centrism is endlessly presented in the media as the only viable political position.

For most care-givers, however, these people are the enemy. If you are a nurse, for example, you are keenly aware that it’s the administrators upstairs who are your real, immediate class antagonist. The professional-managerials are the ones who are not only soaking up all the money for their inflated salaries, but hire useless flunkies who then justify their existence by creating endless reams of administrative paperwork whose primary effect is to make it more difficult to actually provide care.

This central class divide now runs directly through the middle of most parties on the left. Like the Democrats in the US, Labour incorporates both the teachers and the school administrators, both the nurses and their managers. It makes becoming the spokespeople for the revolt of the caring classes extraordinarily difficult.

I liked this, from David Graeber, which is of course about much more than last year’s depressing election in the UK. —It provides a certain clarity lacking in recent heated disputations, and recalibrates what’s seemed to be ineluctable math: I mean, if we’ve got to have an US and a THEM (and when there’s a fight, we do, yes, we do), then give us an US that everyone wants and a THEM no one wants to be (not so much the people that comprise it as the systems and rules and expectations, the bullshit, that generates and enforces the roles they end up playing; one is attempting, as ever, not to become as sounding brass, or a tinkling cymbal). Care-giver versus administrator! (And not Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right, or PMC against Chapo Dirtbag.) —This a battle we all can join with a sunny heart.

The answer, I think, lies in the emerging structure of class relations in societies like England, which seems to be reproduced, in one form or another, just about everywhere the radical right is on the rise. The decline of factory jobs, and of traditional working-class occupations like mining and shipbuilding, decimated the working class as a political force. What happened is usually framed as a shift from industrial, manufacturing, and farming to “service” work, but this formulation is actually rather deceptive, since service is typically defined so broadly as to obscure what’s really going on. In fact, the percentage of the population engaged in serving biscuits, driving cabs, or trimming hair has changed little since Victorian times.

The real story is the spectacular growth, on the one hand, of clerical, administrative, and supervisory work, and, on the other, of what might broadly be termed “care work”: medical, educational, maintenance, social care, and so forth. While productivity in the manufacturing sector has skyrocketed, productivity in this caring sector has actually decreased across the developed world (largely due to the weight of bureaucratization imposed by the burgeoning numbers of administrators). This decline has put the squeeze on wages: it’s hardly a coincidence that in developed economies across the world, the most dramatic strikes and labor struggles since the 2008 crash have involved teachers, nurses, junior doctors, university workers, nursing home workers, or cleaners.

And if this move seemed odd, a bit redundant, somewhat unnecessary—“service work” does a fine-enough job delineating that US as it is, and of the three classes he’d cleave away (clerical, administrative, supervisory), it’s only ever really the clerical that gets fitted with a pink collar—the need to refine gives us just enough room to make sure the “care” in care-giver’s expansively defined, increasing our US, decreasing THEIR thems.

Whereas the core value of the caring classes is, precisely, care, the core value of the professional-managerials might best be described as proceduralism. The rules and regulations, flow charts, quality reviews, audits and PowerPoints that form the main substance of their working life inevitably color their view of politics or even morality . These are people who tend to genuinely believe in the rules. They may well be the only significant stratum of the population who do so.

But of course I’m going to latch onto this: I’m a professional manager in a decidedly PMC workplace—but a workplace with a mission to give what care we can to folks cataclysmically enmeshed in those rules, those regulations, those procedures, our laws. —I know which side I’m on, y’all. I know where I need to stand.

“The law, in its majestic equality, forbids rich and poor alike to sleep under bridges, to beg in the streets, and to steal their bread.”

After more than two years of frustration from people who live in houses and in tents along interstate corridors, the city of Portland will take over campsite cleanup duties from the state transportation department.

Residents were baffled over whom to contact about trash, needles and other issues they saw along multi-use paths and sidewalks that run along highways. The city had no jurisdiction to clean up homeless camps, and the Oregon Department of Transportation was hard to get ahold of and slow to act, residents complained.

Meanwhile, homeless people who wanted an out-of-the-way spot to stay for a few nights said that they were never referred to social services and often didn’t know whose cleanup schedule they would be rousted by.

Wednesday, the Portland City Council unanimously approved an agreement with the department of transportation to use the city’s One Point of Contact system to field complaints and prioritize them for cleanup on the city’s schedule.

The partnership also brings a change in the schedule. Campsites will be notified that contracted crews will come to bag garbage and move tents at least 48 hours prior.

That is a compromise between the city’s 24-hour posting minimum and the state’s 10-day notice.

That went down just over a year ago. And it sounds lovely, doesn’t it? A decision that alleviates frustrations, providing clarity to both the people who live in houses, and the people who live in tents?

As Mayer tells it, earlier in 2019, Debbie had hip surgery and “was released to the street.” In July, Debbie, together with her husband Scott, and a number of other houseless people, were camped along a fence line in Southeast Portland, in close proximity to the Sunnyside Community House, where she found community, a couch to crash on, and coffee and warm meals.

“She was just a feisty, wonderful, strong woman,” Mayer said, “but she couldn’t walk very well for the last few months.”

In mid-July, the campsite was swept by the city-contracted Rapid Response Bio-Clean team, and, Mayer recounted, Debbie “lost all of her meds that day. She was on a series of eight or nine medications,” including antidepressants and insulin for her diabetes. “She lived her last days without them,” said Mayer, detailing the arduous lengths that houseless people have to go to in an effort to reclaim items taken during sweeps—from the last of their family photos, heirlooms and mementos, to ID and life-sustaining medications like insulin. People are not always able to retrieve the items, and in the cases when they are able to retrieve them, the items are sometimes contaminated and unusable.

The city mandates 48 hours’ notice before sweeps teams are allowed to move on the scene. A 48-hour window for moving, if you haven’t been on site for long, might not be that challenging if you’re in your 30s and don’t have any number of disabilities and health issues that are so common on the street. Of course, according to a recent study in Lancet, which encompassed multiple countries, including the US, if you’ve been on the street for any length of time, the odds are pretty good, about 53%, that you will have suffered a traumatic brain injury, whether before or in the course of being homeless. And if you’re pushing 60 like Debbie, a diabetic struggling with depression, in the midst of recovering from a hip operation, toting around the last of your worldly possessions, 48 hours might be a bit of a challenge.

But 48 hours is the mandatory window for notice before the team arrives to scour the scene. The 48-hour notice, Mayer tells me, doesn’t apply if the site has been swept within the past 10 days. So on July 24, Rapid Response returned to the site unannounced. And with no one about, they began taking down and collecting tents, whereupon they discovered the body of Debbie Ann Beaver.

Mayer said the Rapid Response team “noted her as deceased and did not attempt to revive her.”

I spoke by phone with Lance Campbell, the owner of Rapid Response Bio-Clean, who informed me that on discovering Debbie’s body, the workers, who were not trained in CPR, immediately called 911. He indicated that the police arrived on the scene within a few minutes and sealed off access to not only the tent but to the broader area, cordoning it off with police tape.

Mayer said no ambulance ever appeared on site, and at some point, Debbie’s body was placed in an unmarked white van, “and everybody just drove away. All the police disappeared at once, and nobody said anything to anybody.”

There ain't no such thing as a backyard leftist.

“As Washington Monthly points out, Hogan wins praise from ostensible liberals for being a ‘Republican who believes in climate change,’ but his administration has devoted itself to constructing automobile infrastructure over public transit. This is one of the most difficult things to get American voters to believe, but if you support state politicians who constantly build and expand highways, you do not support mitigating climate change. Larry Hogan may ‘believe in’ climate change, but he does not wish to do anything to stop it, especially if accelerating it is good for his own bottom line.” —Alex Pareene

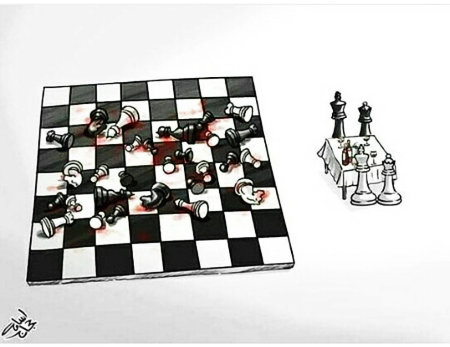

One-dimensional chess.

“No amount of brute force can hold the neoliberal order together—and Trump is not trying to hold it together. Rather, he and his fellow nationalists aim to ensure that the conflicts that succeed the neoliberal order will play out along ethnic and national lines rather than uniting everyone against the ruling class he represents. Case in point: the Iranian government, threatened by massive unrest scarcely two months ago, can now use the escalating conflict with the US to legitimize its authority domestically.” —CrimethInc.

A bad memory of policing in this country.

“But it changed our family, even if we never discussed it. We no longer spoke Farsi in public. My mom stopped saying hello to our neighbors as she got the mail. My dad lowered the Persian dance music from his car stereo before turning onto our street. My brother, Sohrab, began to go by ‘Rob.’ And I borrowed the interests of my white peers: Lunchables, cheerleading and country music. I changed the way I dressed to fit in with the Abercrombie & Fitch girls in my class. I chemically straightened my thick, curly hair until it flowed straight down my back in sleek strands. I second-guessed the food I ate at lunchtime: Persian stews served with rice were swapped out for PB&J sandwiches in brown paper bags.” —Farnoush Amiri

“It doesn’t matter that we started it”

Over on the Twitter, Lili Loofbourow reminds us of this cracking David Graeber essay, on bullying, and power:

Here I think it’s important to look carefully at how institutions organize the reactions of the audience. Usually, when we try to imagine the primordial scene of domination, we see some kind of Hegelian master-slave dialectic in which two parties are vying for recognition from one another, leading to one being permanently trampled underfoot. We should imagine instead a three-way relation of aggressor, victim, and witness, one in which both contending parties are appealing for recognition (validation, sympathy, etc.) from someone else. The Hegelian battle for supremacy, after all, is just an abstraction. A just-so story. Few of us have witnessed two grown men duel to the death in order to get the other to recognize him as truly human. The three-way scenario, in which one party pummels another while both appeal to those around them to recognize their humanity, we’ve all witnessed and participated in, taking one role or the other, a thousand times since grade school.

The application of which to our current moment is made historically clear from the jump—

In late February and early March 1991, during the first Gulf War, US forces bombed, shelled, and otherwise set fire to thousands of young Iraqi men who were trying to flee Kuwait. There were a series of such incidents—the “Highway of Death,” “Highway 8,” the “Battle of Rumaila”—in which US air power cut off columns of retreating Iraqis and engaged in what the military refers to as a “turkey shoot,” where trapped soldiers are simply slaughtered in their vehicles. Images of charred bodies trying desperately to crawl from their trucks became iconic symbols of the war.

I have never understood why this mass slaughter of Iraqi men isn’t considered a war crime. It’s clear that, at the time, the US command feared it might be. President George H.W. Bush quickly announced a temporary cessation of hostilities, and the military has deployed enormous efforts since then to minimize the casualty count, obscure the circumstances, defame the victims (“a bunch of rapists, murderers, and thugs,” General Norman Schwarzkopf later insisted), and prevent the most graphic images from appearing on U.S. television. It’s rumored that there are videos from cameras mounted on helicopter gunships of panicked Iraqis, which will never be released.

It makes sense that the elites were worried. These were, after all, mostly young men who’d been drafted and who, when thrown into combat, made precisely the decision one would wish all young men in such a situation would make: saying to hell with this, packing up their things, and going home. For this, they should be burned alive?

—our “current,” eternally returning, horizon-closed, Groundhog-Day’d moment.

And sure, tell yourself Trump’s the bully, and we’re the witness, the audience, but Trump is also very much the audience, being appealed to by Pompeo and the Fox Newsocracy as they ’it ’im again—the soul of our nation (such as it is), the lives of thousands if not millions of people, will be battled over by our very own self-inflicted Haw-Haw, and Tucker fucking Carlson, and I’m not sure where Chris Hayes fits into this trialectic—

—but he works for an organization that fired Phil Donahue for far less reason than they ever had to fire Matt Lauer.

This is difficult stuff. I don’t claim to understand it completely. But if we are ever going to move toward a genuinely free society, then we’re going to have to recognize how the triangular and mutually constitutive relationship of bully, victim, and audience really works, and then develop ways to combat it. Remember, the situation isn’t hopeless. If it were not possible to create structures—habits, sensibilities, forms of common wisdom—that do sometimes prevent the dynamic from clicking in, then egalitarian societies of any sort would never have been possible. Remember, too, how little courage is usually required to thwart bullies who are not backed up by any sort of institutional power. Most of all, remember that when the bullies really are backed up by such power, the heroes may be those who simply run away.

Terrifyingly serious, casually bigoted, deliberately absurd:

“Since the murder of Heather Heyer by a white supremacist in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August of 2017, I’ve been regularly watching discussion boards on 8chan and the neo-Nazi website Stormfront to better understand what I call ‘8chan Medievalism.’ I wanted to examine how the worst people in the world talk about the Middle Ages within their own Internet safe spaces. What I’ve found is that the problem has gotten worse online, even as 8chan medievalism has shown up in the writings of mass-murdering terrorists and would-be terrorists.” —David M. Perry

High turnover, low inventory, mostly cash—

a Sunday afternoon seminar in money laundering (twitter; threaded) that starts with a weed dealer and a sub shop, and ends with the bulk of the wealth of the world. Your basic TL;DR: “If we were serious about crime, we’d take most of the cops off the streets and replace them with accountants. Taking down the financial underpinnings of a criminal enterprise is way more effective than busting their entry level contractors.”

He said, he said.

People like you are still living in what we call the reality-based community. You believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality. That’s not the way the world really works anymore. We’re an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you are studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we’ll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that’s how things will sort out. We’re history’s actors, and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do.

—a senior advisor to Bush fils, as interviewed by Ron Suskind

No. When you have power, you don’t take responsibility for abusing others. You enjoy the power. That’s the way it works in reality.

—Terry Gilliam, as interviewed by Alexandra Pollard