For your consideration:

Little Dee, the new daily strip from Chris Baldwin.

DESTROY!!

ITEM!! Radio blowhard and professional bully Lars Larson heard that Cleveland High School’s Sexual Minorities and Allies group was planning an outdoor screening of Hedwig and the Angry Inch! Seeing this as some sort of backhanded slight to his own manhood, Larson egged his reactionary audience into a telephonic bashing of such epic proportions that it shut down the school’s phone system! The school with no small amount of exasperated eye-rolling and long-suffering sighing canceled the dick-chick flick to assuage these small-minded bullies! Larson and his sycophantic ilk may strut and preen for now, satisfied in having smacked down a bunch queer ‘n’ questioning kids who never did nothin’ to nobody, but the last laugh’s on him: the Portland Mercury is sponsoring their own outdoor all-ages showing! Guess what, Larson: it’s a free fuckin’ country! So bite me! Monday, 7 June, 8 pm, at Pacific Switchboard!

ITEM!! The beleaguered Cheney-Bush campaign for the presidency planned a public stop at Kalamazoo College to be hosted by the campus College Republicans! Curious liberal students who wanted to see what all the hubub was about stood on line in the rain for two hours to get tickets! They dressed in mufti—khakis, sweaters, no bumper stickers or banner ads of any sort—and arrived at the public event promptly! But they were turned away at the door for failing a background check! It seems College Republicans had been trained to spot potential threats and fingered the subdued libs based on their reputations alone! When the libs attempted to assert their right to attend a public event, police were summoned! Arrests were threatened! They were informed this public campaign stop was actually a private event, closed to all but a vetted audience! We ask you, ladies and gentlemen, and all the scientists at sea: What does Cheney-Bush have to hide?

ITEM!! Scott McCloud’s seminal DESTROY!! was the first ’90s comic, say some; THE LOUDEST COMICBOOK EVER! bellow others! Its deceptively simple storyline makes wild mockery of the dialectic in which each side cries to the other, “You are stupid! And I will SMASH YOU!” Which makes it a stunningly prescient work of political satire! But don’t let “satire” fool you: it’s also great fun and a cathartic read! And the original artwork is a stunning addition to your home or office! (Management has for many years rejoiced in the classic “DESTROY! SHUT UP! DESTROY! SHUT UP! DESTROY! SHUT UP!” page.) This factoid is mentioned because only a few pages are left, but they are humdingers! Only $250 each! Management humbly commends the following page to your attention—

Courage! Bush is a noodle!

Comics, juxtaposed.

First, there’s Bill Mudron doing Pan.

Then, there’s Chris Baldwin filling in for the Spouse on Dicebox.

Because, you see, having finished Chapter 3, she’s off channeling Edward Gorey as she fills in for Dylan Meconis on Bite Me!

And while you’re over at Girlamatic, you might want to pop in on the debut of Barry Deutsch’s Hereville.

And, heck, finish it off with the photos snapped by Winter and Sky McCloud of their dad goofing around with 24-hour cartoonists up and down the lower half of California.

Ignoring for the moment that neither Sky nor Winter

nor Scott nor Ivy is visible in the sample photo above.

In other comics news.

Well. That last bit ended up somewhat more… messianic than I’d expected. Um. Anyway, I wanted to note a couple of other things:

- 24 April is 24-Hour Comics Day. What is a 24-hour comic, you ask? Simple. Sit down with 24 pieces of paper and a marker. Eyeball the clock. Start writing and drawing a 24-page comic book. 24 hours later, stop. There you go. Scott McCloud invented them back in the day, and they’re one of those things everybody should do at least once, like skydiving, or dropping acid: it’s a kick-ass shamanic rush. (See also: 24-hour plays.) —The Spouse has a bit more information; I’ll join her in saluting old friend Paul Winkler for making it into the seminal 24-hour comics anthology that marks the occasion.

- Barry’s going to be doing a weekly strip for Girlamatic called Hereville. Hey—we all loved his political cartoons, but the man is a storyteller, first and foremost, so yay! It starts 6 May—sign up now, and tell ’em Barry sent you! (Or Jenn, if you like. Or just catch the free page every week, if you don’t want to pony up the $2.95. Cheapskate.)

- Jenn’s finishing up the third chapter of Dicebox this week. Two years, three chapters done, and the prologue’s over; now, she says, the main story can begin. —Well. After a bit of a break. Chris Baldwin—who’s currently trying to launch his unutterably charming daily strip, Little Dee, will be doing a back-up Molly and Griffen strip for a couple of weeks, to give Jenn some time to rest and recoup. (Which is good. I’ve missed her.)

Don’t dream it, be it.

I don’t know how Kazu pulled it off: somehow, he got hold of Scott McCloud’s comics retrospective from 2054.

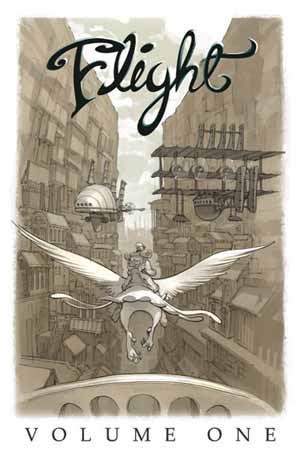

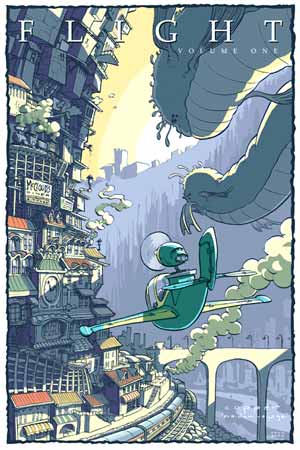

I’ve seen preview pages—he’s only being slightly hyperbolic. Flight (vol. 1; vol. 2 is in the works) is a 208-page color anthology of short works by some of today’s (say it with me) best and brightest: Kazu Kibuishi, Vera Brosgol, Derek Kirk Kim, Clio Chiang, Jen Wang, Erika Moen, Dylan Meconis, Hope Larson, Bill Mudron, Rad Sechrist, etc. etc. —I’ve nattered on about some of these folks before; this is nothing more or less than the next turn in the widening gyre.

It’s going to be an important book—not, y’know, an important book, full of meatily literary comics that wring the meaning of life through the juxtaposition of pictorial and other images in a deliberate sequence; no. For one thing, it’s an anthology, which is always hit-or-miss (though my hits are usually your misses, and neither of us can figure out why she liked the thing with the cat). And there’s featherweight pieces in here: beautiful and charming and evanescent as a soap bubble, pop! Which is fine: it never set out to be an important book, after all.

Nah, it’s going to be important because it’s going to serve notice. It’s going to make a lot of people realize how far along things really are. It might even do some polarizing.

Scott cites four reasons as to why this book is going to be important right now. The second reason, “tribal shift,” does a pretty good job of encompassing the rest. (You could say the same about the web striking back, the metabolization of manga, or the changing face of comics, if you wanted. Me, I’m sticking with the tribes.) —He’s referring to his four tribes map, and if Erika hadn’t let her photo archives slide off into link rot, I’d show you the picture of the placemat he sketched it on for us in Seattle. There’s broadly speaking four ways you can split the [insert creative enterprise here] community: animists, classicists, formalists, and iconoclasts, with the animists across the table from the formalists, and the classicists across from the iconoclasts. (You can line out the semiotic square if you want.) —Sure, there’s other ways you can split them; there’s dozens, hundreds, thousands. So what? This is the map we’re dealing with right now, and with this map, Scott says (and aw, heck, I’ll just gack the thing whole):

In the decade prior to Flight, most of the progressive wing of comics was dominated by the Iconoclast and Formalist Tribes. Walking through the turn-of-the-century expositions devoted to “small press” comics, visitors were greeted on one side of the aisle by roughly drawn “zines” about disaffected white youths with bad jobs, failed relationships and genital warts; and on the other by strange, multidirectional experiments and oddly shaped cardboard constructions with day-glow silkscreen covers. I loved both types of comics (and make no apologies for my alleged complicity in the latter) but by 2004, a change was clearly in the air.

The return of the other two tribes to independent comics found its focus in Flight. The Animists’ love of pure transparent storytelling and the Classicists’ attention to craft and enduringly beautiful settings was evident on many of the anthology’s pages. While so many of the previous generation’s revolutionaries had put raw honesty and innovation over straightforward plots and surface gloss, the Flight contributors tried to have it all—and in several cases succeeded. Flight gave readers something to read and something beautiful to look at again and again. For all the innovations of the rebel tribes, it was this kind of appeal to a broader readership that comics desperately needed in 2004. These artists delivered.

Top Shelf and Drawn & Quarterly and Kramer’s Ergot and Blab! and Zero Zero and Centrifugal Bumblepuppy on back to the grandparents of the iconoclast and formalist tribes, Weirdo and Raw: these anthologies have done incredible, unmistakable things for comics, and it’s impossible to imagine the medium without them, and you’d have to pry my grubby, well-read copies from my cold, dead hands (unless you asked nicely, and then I’d say sure), and Flight is the first major comics anthology I could hand off to my mother, my boss, the woman at the next table, the kid on the bus, you, anybody, and feel pretty damn sure they’re going to sit up and say wow. Oh, I see. Oh, I get it.

Comics as an industry has been its own sequestered, ghettoed hot-house for a very long time, locking comics the medium away in direct-market shops out of the sight of the casual walk-in, held back by the overwhelming popularity of the superhero from people who just don’t give a damn about superheroes. Classicists work in the footsteps of great superhero cartoonists; animists summon up the bubbling Saturday-morning glee, all in color for a dime; and maybe iconoclasts work the rich veins first tapped by the underground cartoonists of the ’60s, and formalists delight in a really spooky borderland between word and image—but they’re still laboring in the shadow of the superhero, and they’re still mostly found in the same shops off the beaten path, snarling at the four-color hand that feeds them.

It’s getting better, sure: it has been, for years, but there’s still plenty of otherwise bright people out there who insist, say, that the swelling popularity of translated manga is just a passing fad, and not a hint of what comics can do when they open up to a broader palette of genres, and put themselves on bookshelves where anyone can find them. —Though that’s unfair: it’s too easy to say the people who agree with me get it, and the people who don’t just don’t. And just about everybody gets it: comics have to open up or die. Comics have to reach out or wither away. Comics can’t just be a monoculture of superheroes. We all know this, and we’re opening up and reaching out, and it isn’t a one-trick pony, not nearly so much as it used to be. Almost everybody gets it. It’s the system that doesn’t: everything from editorial direction to publishing prejudices, from the monopolistic distributor to the retailer’s shelving decisions, from an otaku’s culling of their monthly buy list to a reviewer’s hype—all the hundreds of thousands of little decisions made without thinking, honed by habit to fit a market that sells one thing moderately well to a captive audience. There are good reasons (and bad, and head-smackingly stupid) as to why that system came about, but that’s what we’re all trying to fight, or at least change: habit, and that’s why it’s so damned hard.

Flight is a huge, full-color package winging in from the everything outside that habit. It’s the manga fans, who love comics, but came at them by way of Japan (with a healthy injection of Europop, by way of France). It’s the animation freaks, who find in comics a way to build the worlds they’ve loved on screen on their own, without the expense and (quite so much) labor. It’s the web cartoonists, who’ve built their own gift-economy shadow industry online, utterly outside the purview of a micro-mass market that’s only had room for one genre. It’s anybody who loves the way comics opens up whole new worlds, every panel a shadowbox peering into perfectly personal universes, and here’s where I check Dylan Horrocks’ essay again without doing the heavy lifting needed to engage it fully, but hey: it’s anyone who sees the worlds that comics can build, but didn’t care much for the one (bright and garish and exhilarating and terrifically fun world, sure) that we’ve built with it so far. That’s what went into Flight, and that’s what Flight is bringing into the direct market, and that’s why Scott’s introduction doesn’t read so much like hype. —Well. Except for the bit about Claire Danes. But aside from that.

(It’s solicited in May’s Diamond catalog, by the way, and slated to hit the shelves the weekend of the San Diego Comic-Con, 22 – 25 July. Until then, you can whet your appetite with the preview pages.)

Power to the people! Teeth for shrimp! Plato was a fascist!

Chris Bertram over at Crooked Timber brought up Harry Perkins, the fictional prime minister from A Very British Coup, in the course of a post that seems cheekily to suggest we Yanks are a bit more starry-eyed and less cynical than Brits when it comes to pop culture representations of our respective Fearless Leaders. (This is not necessarily a bad thing, mind. Do remember that the monolithic Left controls the entertainment industry in both realms.) Coup is a hardnosed political thriller, but it’s leftist, socialist, old skool Labour politics, and that makes all the difference. A great little fairy tale; highly recommended when you want a little dose of mightabeen. (I’ve only ever seen it up at Skook’s place, where I imagine it’s still a rainy-day security blanket..?)

Being reminded of Harry Perkins reminded me in turn of J Daniels’ bootleg Tintin comic, Breaking Free, in which the boy reporter, on the dole after being sacked from a dodgy construction job, joins up with the Captain and just about every worker in Britain in a popular uprising, peacefully overthrowing the corporatist state in favor of a happy anarcho-socialist people-powered muddle. It’s heartbreakingly hopeful and hoplessly naïve; another fairy tale that I adore. You can buy it, of course, but while trying to scare up the links I discovered it’s also available online. Enjoy.

April punk’d.

“Oh, geeze,” says a friend of mine, who actually works in the industry, when I told him about the whole Tony Millionaire thing. “I just figured he was posting drunk again.”

You know, if Dirk Deppey were still kicking it, none of this would ever have gone as far as it did.

Oh, but that’s no excuse. I posted the link, and the write-up; I kicked it up to Atrios, who bit; and even though I admitted I was unsure of the whole shebang, I stacked the deck with I’d thought was a reasonably coherent translation of what it was Millionaire was reporting, but in retrospect, looks a little too much like me, who worked as a managing editor for a tiny little alternarag for a bit, imposing my own sense of what must have happened to make some sense out of what it was Millionaire was reporting. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is why it’s probably a good idea I stay away from your more journalistic endeavors: I’m all too willing to carry water for whatever my immediate take on the story is (must be), skipping blithely down the paving stones of my own damned good intentions.

1995: Acting on a tip from Oklahomans for Children and Families, undercover police officers purchase adult comics from the box Planet Comics kept behind the front counter, where kids couldn’t see them. Then the shop was raided. The shop’s owners, Michael Kennedy and John Hunter, were charged with four felonies and four misdemeanors for selling adult comics to adults. The shop was evicted and had to relocate. Sales plummeted. Cops raided Hunter’s home and confiscated his computer. Somebody heaved a brick through the store’s window one night. A divorce was filed. Hunter and Kennedy plead guilty to reduced charges, got three-year deferred sentences and fines of $1,500 each. Bob Anderson, the president of Oklahomans for Children and Families, said his group was opposed to censorship, but “There is also material that is not illegal which is not suitable for children under [Oklahoma’s] harmful-to-minors law. And who buys comic books but younger children?”

(Then Oklahomans for Children and Families went after The Tin Drum. The ACLU shut them down, hard. They don’t even have a website anymore.)

“Attorney General Hardy Meyers’ office.”

“Um, hi. I’m trying to look into claims that—well, there’s a letter that apparently was written by Attorney General John Ashcroft directing state attorneys general to aid him in cleaning up comic strips? And I’m trying to find out if this letter was really written?”

“Goodness. It sounds like you need Financial Fraud and Consumer Protection. Hold on a moment.”

“Financial fraud—?”

“Hi, this is Kevin. I’m not available right now, but if you leave your name and number…”

I suppose the clues are there if you want to look for them. “I’m growing it for the ‘April Fools,’ says Uncle Gabby, after all. And even if Millionaire backed off from the absurd claim that the FCC made him do it, his story’s still incoherent at best. The way it’s written, it sounds almost as if the three editors who requested the change in wording did so under specific instructions from their attorney(s) general: as if these public servants were poring over pre-release copies of Maakies and Dwarf Attack to determine if younger readers might be harmed by anything these pen-and-ink contraptions might say, before publication. This is absurd, of course. —But if it is all a joke, why would Millionaire take it so far? Posting thick chunks of Ed Meese’s famous Attorney General’s Commission on Pornography report? Going on the record with The Pulse? —Verisimilitude, of course. What’s the use of a prankish publicity stunt if you cave on the first salvo? And he’s been notably reticent about letting slip any actual facts that might back up what he’s saying: “I find it interesting that fuck you,” he says. “Are you the prosecuting attorney or my mother? Because if you’re my mother I guess I’ll have to answer you,” he says. — So what? Why does he have to answer every single one of our questions about this? Why can’t he be a grouch? Maybe it’s irresponsible and maybe it’s even dumb, but it’s hardly proof that he’s lying. Maybe he’s posting drunk, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a kernel of truth in all this. Maybe he got his facts out of order. Maybe the editor(s) in question lied to him. Only one is claiming it came from their attorney general somehow, after all, and maybe they’re getting their facts wrong, and there was never a letter from Ashcroft at all. Wouldn’t be the first time some cowboy went after the funnybooks for perfectly stupid reasons. —But cowboys want noise, bright lights, big rooms full of an adoring public grimly celebrating another hard-fought kulturkrieg. You don’t get noise and lights and big rooms with a quiet request to back down to “vagina” from “cunt.” Doesn’t make for good headlines. You know?

1994: Michael Diana used to do an underground comic called Boiled Angel. In 1990, someone rather brutally killed five women in Gainesville, Florida, on and around the University of Florida campus. Solely on the basis of the story and art in Boiled Angel no. 6, investigators decided Diana was a plausible suspect. The cops later picked up the real murderer when he tried to rob a Winn Dixie. —In 1993, a state attorney going through the old case files stumbled over more issues of Boiled Angel and decided Diana’s stuff was obscene; Diana had to be stopped. A jury determined that Boiled Angel had no literary or artistic merit. The terms of Diana’s three-year probation allowed his house to be searched at any time without warning or warrant for evidence that he either possessed or was creating obscene material. Psychological testing was mandated. He paid a fine of $3,000. And he was allowed no contact at all with anyone under the age of 18. (A prohibition against his drawing anything at all was later dropped.)

“Hi, this is Kevin. I’m not available right now, but if you leave your name and number, I’ll get back to you as soon as possible.”

“Um, hi. This is Kip Manley again. I left you some voicemail yesterday? I’m just trying to confirm this, uh, this claim that there might be a letter, from Attorney General John Ashcroft, directing states to look into, um, cleaning up or even, I guess, censoring comic strips in newspapers. This cartoonist says his editor told him he was told by somebody that this was the case, and, um. Anyway. You can reach me at my work number, during the day, or at home, in the evenings. Um. Thanks.”

Reaction was swift (and furious): there was the Fuck Asscroft brigade, of course, and the Comics Journal thread was locked down after an avalanche of what can best be described as juvenalia. Comixpedia assured webcartoonists everywhere that the FCC had no power to regulate content on the internet, and thank God for that. Scott Kurtz did some homework, and ended up throwing up his hands. —But running through a lot of it was a contrapuntal strain: gee, I dunno, I mean, I hate Ashcroft as much as the next person, but that word, y’know, “cunt,” in a comic strip? I can’t believe anybody would try to get away with it in the first place. I mean, what about the children?

Keeping in mind that Maakies appears in the sort of alternaweekly newspapers that run features on trends in group sex at local swingers’ clubs. Where on earth do these “children” come into this?

1999: Jesus Castillo sells a copy of Demon Beast Invasion to an undercover cop in Dallas, Texas. He is, of course, convicted on obscenity charges. —Leave aside for the moment the question of whether or not the CBLDF was rather staggeringly incompetent in their defense of Castillo, and leave aside for the moment whether or not the comic in question is or is not obscene, misogynistic crap, and leave aside for the moment whether or not it was the height of folly for Susan Napier to defend Demon Beast Invasion as filled with symbolism and political themes—literary and artistic merit that justified its pornographic excess. After all, the prosecution did:

I don’t care what kind of testimony is out there. Comic books, traditionally what we think of, are for kids.

What kids? Where?

Looks like somebody didn’t get the memo.

“Mercury.”

“Um, hi. Who’s your comics editor?”

“Our art director is Jen Davison.”

“So she’s responsible for the content of your comics?”

“Yeah. Well, she picks them out.”

“Is she available?”

“She’s on vacation.”

“Oh. Um. Thanks.”

Oh, hey, check it out! Tony Millionaire put the word “boner” in Maakies and 23 newspapers dropped him!

—He said, on April Fool’s. Oh, and he said some more, too:

posted April 01, 2004 08:41 PM

I only wish it was a good joke…

but I got a lot of mileage out of it. two weeks and a hundred bloggers.

blog…..

....sounds like a turd coming out of an ass….

Ha ha. Oh, that Tony Millionaire. Posting drunk. —And was this spectacularly stupid, then, and grossly irresponsible? I dunno. How many more people were prompted to look at Maakies again, or for the first time? How many more Uncle Gabby statues did he sell? How much respect did he lose? (How much did he have in the first place?) Does he owe anything, anything at all, to the larger idea of comics as a struggling medium? Should he go around insulting the legacies of Michael Kennedy and John Hunter, Mike Diana and Jesus Castillo like that? —Sorry. Tried to keep a straight face. Look. It’s not like I’m going to revile the name of Tony Millionaire now. It’s not like I’m going to throw the paper across the room rather than read Maakies ever again. It’s a great strip and he’s a great cartoonist and that’s all I want or expect from him, you know? It’s not like one false cry of wolf! is going to make us all pack up our gear and leave the kultur undefended: there’s plenty of wolves out there yet, and there are plenty of crusaders out there. This is comics we’re talking about, after all.

But, man, Tony. I woulda stuck with “cunt.” Short, pithy Anglo-Saxonisms are always funnier.

PS— Confidential to Michele: Calvin Klein boxer briefs, actually, which don’t tend to wad up in a bunch. But thanks for the concern—and the traffic.

PPS— Oh, hey, I finally heard back just now from Kevin at Financial Fraud and Consumer Protection. “I haven’t turned up a thing,” he says. “But let me tell you: we’ve gotten weirder things from the Department of Justice.”

“Yeah,” says I, “I just found out for sure it was a prank myself. But it sure sounded plausible.”

“Oh,” he says. “It sounds very plausible.”

We are all oblique leftists now.

Belle Waring reminds me (well, all of us, really, I suppose) that the Onion’s underrated AV Club did an interview with Dave Sim on the occasion of getting to 300. Here’s the story behind the interview: what Tasha Robinson had to go through to talk to the man from Kitchener. —Ooh! Here’s more behind-the-scenes Simmery, including a (partial) transcript of the Onion’s recent appearance on The Cerebus TV Show.

Another memo I didn’t get.

So how come nobody told me cartoon journalist extraordinaire Joe Sacco was doing strips for the Washington Monthly? —I’d point you to a couple of examples, or maybe the archive listing so you could browse ’em yourself, but there doesn’t appear to be one, and the Washington Monthly’s front page has no search function (appalling enough for the rather notable blog currently enhancing it; inexcusable for the site as a whole). (Maybe they don’t archive the strips? But why on earth not?)

Anyway, here’s April’s, and I for one will be keeping an eye on Kevin Drum’s sidebar for updates.

300.

Some time early in 1992, when it was still bitterly cold, a bunch of us went down to Boston for Dave Sim’s signing at the Million-Year Picnic. I shared a car with Barry and Kurt Busiek, which meant I kept quiet in the back while they kept up an argument about whether James Bond could strictly speaking be considered a superhero, and for the life of me I can’t remember who was on which side, or why. (I mean, sure, I guess: he’s an iconic figure in a starkly simple, expressionistically drawn moral landscape; more powerful than mortal ken, he lives in a world bent and shaped by the rules of his genre to at once enhance and conform to his role; he has his catchphrases, his signature style, and if he isn’t always wearing a tuxedo, well, the bad guys are usually all wearing the same sort of jumpsuit, so it’s easy to pick him out in a pop art “Where’s Waldo?” fight scene. On the other hand, his underwear is pretty much always under his pants. But I didn’t care to put a dog in this fight then, and I’m only taking it for a walk around the block at the moment. We were, after all, talking about Sim, and Cerebus, and Cerebus isn’t a superhero. So.) —I kept quiet, then, because I didn’t really care, and I didn’t know from Kurt Busiek at all, and I had this secret burning a hole in my backpack.

It’s traditional, after all, to bring something to be signed to a signing, and I had a doozy. The year before, I’d worked as a clerk for New England Comics, and I’d stumbled over a treasure: before he started his aardvark-headed Conan pastiche, Sim worked on a number of freelance art projects, among them the first issue of a Canadian small-press superhero comic called Phantacea. It was about—well, there’s this kid who walked with a couple of orthopædic crutches who really loves Baron Justice comics only his Scottish grandfather (“Laddie, have ye naught to do but read this smut?!”) doesn’t like him reading this garbage because it will give him ideas just like it gave the boy’s father ideas to dress up as a superhero and fight crime as Baron Justice only he doesn’t do that now because he’s the head of security for a mad scientist who’s building some sort of gravity train to alpha Centauri except this Romani master of electromagnetism who helped design the gravity train has decided it’s a misguided effort doomed to disaster and is determined to stop it any way he can even if it means going through the boy’s father to attack the train itself only the boy after he fights a mugger to save a little old lady (“Justice for all!” cries the caption box. “If a cripple can help—why can’t you?”) finds his father’s Baron Justice costume in the attic I think and he decides to put it on and fight crime even though the orthopædic crutches are going to make the whole secret identity thing problematic except oh my God! The train has launched! What will we do! See you next issue, pilgrim!

I don’t think there was a next issue. (Google: oh, wow. There was. There were several. Oh, my. It’s still sort of going on. Oh, goodness.)

Anyway. That’s what I had in my backpack. Phantacea #1.

So we end up at Million-Year Picnic and stand in the long line and the guy ahead of me is asking some really long convoluted question about Cerebus continuity (what had become of the false albatross, maybe), and Dave has signed whatever it was he was going to sign for the guy and he waves him along and it’s my turn. So I reach into my backpack. To his credit, he grinned and rolled his eyes when he saw the oversized bright magenta cover. “I really liked what you did with Jaka’s Story and Melmoth, Mr. Sim,” I said. “But I think I liked your earlier, funnier stuff better.”

Ha ha, right? He suddenly gets this serious look. “You know,” he says, “everybody thinks Woody Allen was kidding when he said that. But he was serious. That really happens. People really do come up to you and say that stuff.” He starts drawing a quick Cerebus head on the inside front cover of Phantacea #1. I make a noncommittal noise, something not unlike “Uh-huh.” The guy who’d been ahead of me says, anyway, about the Conniptins, and Dave looks up at me and says, “You going to let him take up your time?” and I kind of shrugged. I’d pulled off my great joke. I’m lousy meeting people I admire for the first time. My tongue was tied. Dave signed the sketch with a flourish and never got around to answering the guy’s question about Onliu Diamondback variants.

That’s my Dave Sim story. It was funnier then than it is now.

I stuck it out through Guys, looking back, and most of Rick’s Story, which I never got around to finishing. (The Spouse made it through Going Home, I think.) For all his faults (and they are legion), Sim’s the best fucking cartoonist on the North American continent, and up there in the pantheon of Best Ever Anywhere for All Time. His lettering, sure; his unparalleled ear for dialogue and dialect; his spot-on caricatures of Groucho Marx and Mick and Keef; his acerbically satiric edge and the loopy mysticism that kept leaking around the edges, making the world a bigger and weirder place than it had any right to be, to step away from the strictly speaking cartooning portion of the proceedings. His flawless compositions, his fearless bending and melding and splintering of panels, his design sense, his ability to make a whole page—a whole issue, a whole run of issues—work as a tightly considered unit in a staggering variety of styles that juggernauted from belly laughs to wailings and gnashings of teeth. His brilliance in scooping up the last of the Renaissance masters to painstakingly work out the perspective in all his backgrounds and cross-hatch them into things of beauty (Gerhard, take a bow, man; you more than deserve it). His quixotic stand for self-publishing in the face of all else, to step away from the cartooning again, and his not-so-quixotic stand for creators’ rights and the importance of the cartoonist over the importance of the property (and yet, while a lot is made of his influence over self-publishing successes such as Jeff Smith and Terry Moore, not so much is made of the influence his cartooning has had on folks like Alex Robinson, who wears it well). —There’s a simple, beautifully cinematic sequence in Guys that’s just a piece of paper blowing away from Cerebus; the paper stays in the foreground of each panel, and Cerebus and the background drop further and further away from us—it’s simple and wordless and flawless and perfect.

For God’s sake, the man figured out how to letter an echo.

So even if he’d snapped and murdered a busload of nuns, I’d say you ought to have High Society and Church and State and Jaka’s Story and Melmoth on your shelf, you want to be a serious student of comics. Of course, he didn’t snap and murder a busload of nuns. He snapped and started saying women were dark consuming voids who latch onto male lights of reason and suck away their vital essences for nourishment and so men are vastly better than women and here’s the long, painstaking, Ditkoesque proof.

—It’s a little more complicated than that.

There’d always been a tension between Sim the Polemicist and Sim the Novelist in Cerebus. Sim the Novelist used to win, hands down, every time, letting Sim the Polemicist out for a bit of exposition now and then, and otherwise keeping him confined to the Notes from the President and the letters column, where he got up to some mischief now and again, but otherwise stayed mostly out of trouble.

Now, in Jaka’s Story, Sim had indulged himself with illustrated set-pieces written in a rich pastiche of Wildean prose, rather than straightforward comics, as a technique to distance Jaka’s privileged past apart from the moment-to-moment comics storytelling of the all-too-quotidian present. Some think this worked really well and some think it stopped the story dead, but it was all still the work of Sim the Novelist. It wasn’t until the metafictional set-pieces of Reads, where he interspersed an argument and a bloody fight scene that lasted for issues with long text pieces—at first, a roman à clef of the comics industry staring a certain Victor Reid, whose creative life collapses when he sells out to a big publisher and gets married; then a not-so-roman with an even thinner clef: evidently autobiographical essays from the soi-disant Viktor Davis, who began to tell us what it was like, doing Cerebus: roads taken, and not. —Now, here, Sim the Polemicist was starting to leak through, but it was at least as a technique okay. Reads was the apotheosis of Mothers and Daughters, his blockbuster follow-up to the relatively quiet, contained novel-and-epilogue of Jaka’s Story and Melmoth. Old characters going back years were brought back into the plot, and threads left dangling for years were picked back up and held, tantalizingly, just out of reach. Reads begins with the four prime movers of the story-that’s-finally-being-revealed (Cerebus, Astoria, Cirin, and Suenteus Po—three aardvarks, and a human, and if you have to ask at this point, don’t bother) finally gathered together (again for the first time!) in one room; it ends with the aforementioned fight scene. Everything in the comic book was finally coming together. The momentum was almost unbearable. It only made sense that Sim the Polemicist was being sucked in along with it.

And some of the effects were brilliant—backstage comics industry gossip linked with the philosophical themes of freedom and creation; metafictional leaks and linkages between the prose bits and the comics they interrupted—but most notably the trick he pulled in issue 183: he started to write about how he’d been working at Cerebus one night in 1980, about a year after he’d announced that the comic would run for 300 issues to the general scoffing disbelief of the industry.

He [the Viktor Davis pieces are written in the third person; again, a distancing technique] was in the middle of lettering “Blinky Boar and the Strawberry Patch” and humming “Strawberry Fields Forever” to himself when the local radio station interrupted its programming for a news bulletin.

“Possibilities for a Beatles reunion were dashed at eleven o’clock tonight when John Lennon was shot to death outside his Manhattan apartment building…”

That night, Viktor Davis decided that Cerebus would not run for three hundred issues. He decided that Cerebus would run for two hundred issues. Viktor Davis decided to keep this a secret, telling no one for fourteen years.

He would not announce it until issue one hundred and eighty-three, a year and five months before the end: November 1995.

It doesn’t work now, of course, since you know and I know he made it to 300 and right on time, too: March, 2004. But then: I yelled, I think. I gasped for breath. I’d been rabbit-punched. —What follows is almost a page describing the roller-coaster like motion of the ground beneath the reader’s feet, a recreation in prose of some of the trippy, looping effects he’d used in comics, when Cerebus had spoken with Suenteus Po in a magical, illusionary world. It was an impressive linkage of my memories of the comic with what I was reading right then with the very physicality of what I was feeling at that moment as I read: a truly magical evocation of presque vu, about the highest effect you can claw out of a reader.

“I was just kidding,” he said. “Cerebus goes to issue three hundred. Just like I’ve always said. March 2004.”

The reader and Viktor Davis regarded one another for several minutes, without speaking, across the strange, lighted rectangle. Calmly, Viktor Davis withdrew his pack of cigarettes from his hip pocket and selected one. Raising the lighter in his right hand, he lit the cigarette in a quick, easy motion.

“What’s the matter?” he asked, still smiling through a dissipating cloud of smoke.

“Don’t you trust me?”

And then he says, “Bang.” Back in the comic, Cerebus looks up. “Something fell,” he thinks—the two most freighted words in the whole comic. And then, BANG!

It was all about to come together. Everything. The whole shebang so far. Questions were about to be Answered. And given what he’d just pulled off, I’d’ve followed him—Sim the Novelist, Viktor Davis, Sim the Polemicist, whichever—I’d’ve followed him over a cliff. I thought.

What he did, what Sim the Polemicist did, what Viktor Davis did, was rewrite the end of Church and State. That book ends with a creation myth, of the female light of creation being embraced and then smothered by the male void, squeezed until she shatters, sprinkling stars throughout the night sky. Now, though, Davis tells us that it’s a male light, shining bravely, and a female void, smothering sweetly.

And then, in the infamous issue 186, he tells us why.

Unbidden, the image of the Cerebus Theatre swam to the surface of Viktor Davis’ awareness. He turned away from his typewriter and allowed the picture to coalesce in his mind’s eye.

The Cerebus readership was there, composed in some (small? large?) measure of females with their male housepets. He squinted, endeavouring to see if any male was chafing at the invisible conduits and metaphorical tubing which drained his life, his essence, his energy as surely and as effectively as any fictional vampire. Cats’ eyes gleamed in the darkness, filled with malice. A couple of rows back an obese brunette was stripping away chunks of brain tissue from a thin, pale youth with a spotted face. His head lolled against his shoulder in her direction, his face radiant with ecstasy. He turned to her, his eyes half-lidded. He smiled and mouthed, “I love you.” She smiled back at him, indulgently. His eyes closed once more. She stuck out her sandpaper tongue, dotted with brains and blood, in Viktor Davis’ direction and then cackled loudly. The youth giggled quietly to himself.

To the far left, in the front row, the white husk of a heavy-set man in his early thirties squirmed in the direction of his Lady and Master, his features reflecting pain, confusion and fear. She held his forearm in front of her as if they were bound, one to the other, but in such a way that she was also holding him slightly apart from her. Viktor Davis could see that the fellow had been a quick meal—little more than a snack, by the looks of things. Traces of dried brain-matter, hard and uninviting, encrusted what little there was left of the top of his head. She looked very, very hungry. Every few seconds she turned around in her seat, the hunger in her gaze sweeping across the rows to her immediate rear. Females touched by that insatiable stare hunched a little closer to their own housepets, a menacing growl rumbling low in their throats.

Viktor Davis turned back to his typewriter.

“There is no cure for willful stupidity,” he typed and then sat back, cigarette in hand, to contemplate the words.

There’s more. You can read it for yourself if you like.

Issue 186 became something of a flashpoint. You either stuck with Cerebus in spite of it, because of everything else, or you dropped it like a hot potato. You got into knock-down, drag-out fights with people who did the opposite of what you did, if you were so inclined. It might seem these days as if almost everyone dropped Cerebus then and there, but that’s not quite right: things polarized between “I can’t read anything by such an evident misogynist” and “You shouldn’t let his admittedly odious philosophy detract from what he’s done as an artist.” And I’d have to align myself with the latter camp: certainly, I’m willing to put up with all sorts of backstage bullshit I’d never countenance at a cocktail party, say, so long as I get a moment of transcendent beauty every now and then. And Sim had delivered those, in spades. So I stuck with it: we, rather, since it was a communal house at the time, and comics were largely purchased collectively, and most of us wanted to see where he’d go, and how. We’d come this far. (Surely he couldn’t be serious, some of us said, even though we knew we were probably kidding ourselves. Surely this is some sort of joke. “What’s the matter?” said Viktor Davis. “Don’t you trust me?”)

But almost all of us have since fallen away. Because it became clear: he’d built up that momentum not to finally tie it all together, but to sweep the board clean and start over: to clear the clutter he’d been working with and start poking around in a brand new worldview. Sim the Novelist, concerned with character and plot and world-building, had inexplicably surrendered the field to Sim the Polemicist, concerned with axes, and their grinding. He was rewriting. Revising. Revisioning. And his new worldview was based on mean, mean-spirited, and above all stupid logic:

“Men like Cars. Viktor Davis doesn’t like Cars. Viktor Davis is a Man.”

These observations were all true statements. Was it a syllogism? Or was there another name for it? Viktor Davis was uncertain. To the Reasoning Mind and to the Emotional Void, the fundamental structure was sound. They were all true statements, though they appeared contradictory. Using those three statements as a template, Viktor Davis had spent much of his adult life attempting to Reason with the Female Emotional Void. In each case, whatever success he had had (and he had had very little success) had been temporary. He considered his lack of success to be central to the Issue at Hand. Within the context of the Female Emotional Void, no general observation could be considered sound if there existed an anecdotal refutation.

One hardly knows where to begin.

At least Astoria got out while the getting was good.

Because that’s one of the stickier ironies: Sim, misogynist, is responsible for one of the greatest female comics characters ever: Astoria, the political machinator, the power behind Cerebus’ initial rise to power. Cynical, manipulative, self-assured, confident, competent, savvy, imperious, arrogant, idealistic, committed to fighting for women’s rights as part of a larger battle for equality and liberty, she’s the opposite pole to Cerebus’ capricious, hot-headed, stubborn, foolish, oblivious plunge through the plots a-swirl about them. In the climactic, board-sweeping confrontation of Reads, before it dissolves into the (brutal, pointed) fight scene, she has her apotheosis: “Po was right,” she says,

If I’m honest with myself, I’ve only ever wanted power for its own sake… Ostensibly, I wanted to destroy Cirin. As her protégée, I came to despise everyone she kept tabs on—everyone who she felt was a threat to her… I married Lord Julius solely to set up a Kevillist empire from within Palnu… I seduced Artemis and used him to execute matriarchal sympathisers… I seduced her son and made him a glorified errand boy… When you turned up in Iest, I engineered your rise to power. I surrounded you with Kevillists and our symbols. Ultimately, I even became the Western pontiff… A short while ago, the entire city bowed down to me—hailed me as the messiah.

Just look.

I haven’t even made a dent in her—

—power.

Power over others is an illusion, she decides; “a stifling, insulating, frustrating practical joke from Terim… or Tarim. What does it really matter whether it’s a god or a goddess who’s laughing at you?” She remembers a daydream she used to have, as a little girl: a little church, open to the skies. She has several thousand crowns, enough to last her the rest of her life, to build her little house. (She will be mindful of death, and disinclined to long journeys; she will have ships and carriages, but no place to go.) —And with that simple declaration, Astoria walks out of the room and out of the dispute and out of the comic book, never to return.

And if she does return, at some point in those later issues I haven’t seen yet, I don’t want to know. Because I like to think that this simple little goodbye is Sim the Novelist also taking his bow. He’s done. The Age of the Polemicist is at hand.

(That’s on a good day. On a bad day, I think Sim the Novelist is a bastard. I think he typed that line up there, “There is no cure for willful stupidity,” knowing that no Polemicist would ever have the gumption to turn anything he said back on himself—that’s one of the weaknesses of polemic. Sim the Novelist typed one last line, a poison pill, and then he faded to black. Bye-bye.)

We used to sit around wondering what this day would be like. (Idly. Very occasionally. We had other things to do, too, you know.) We’d lock ourselves away for the better part of a week, we figured, with a stack of the Cerebus phone books to hand, and we’d read it through, start to finish, 6,000 pages of comics from a single creator, telling a single story, more or less.

And here we are, in March 2004. He kept his word. We should have trusted him, in that much, at least.

But I’m not rushing out to buy it. We haven’t bought a collection in ages. And I don’t know that I ever will, either. Don’t get me wrong: there’s maybe a handful of people on this planet who have ever worked in comics at his level. His work as a fantasist and a satirist and, yes, a novelist is astonishing. But that’s not enough—because he’s also a dreadful, didactic bore, a muzzy-headed chop-logician with the ever-shifting convictions of his courage. He lost the fight that mattered, with himself; in a very real sense, Sim didn’t make it to 300. —But he made one hell of an indelible mark on comics along the way.

Here’s one for you, then, Mr. Sim.

Even if I do like your earlier, funnier stuff better.

Three simple rules for talking about comics.

First, make like the Lady Montague: never complain, never explain. You’re in this for the hearts and minds, which are impossible to score if you’re always on the defensive. Especially if you’re representing a scrappy little medium that never gets no respect from the major players. Bitching about that lack of respect won’t win you any points; losers bitch, and nobody cares what a loser thinks. And stop with the constantly introducing yourself. Assume you own the room, and you will. Drag queens know this trick, and trust me—people writing seriously about comics are drag queens in the critical apparatus: weird, liminal creatures, floating up out of the demimonde, that knock your socks off in the right light.

So none of this “Comics are a vital, vibrant medium, as capable of adult storytelling as any other” or “Superheroes aren’t merely adolescent power fantasies” crap, okay? It’s just insider baseball for “Bang! Zowie! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!”—and that gag had whiskers when Reagan was president. Don’t sit there clutching at the ground you’ve already got—reach out and take more, and do it with grace and panache and not a little chutzpah. Tell us something we don’t know and make us sit up and take notice or at least make us get the fuck out of the way, and never look back.

Second: suffer no fools gladly—but always be charitable toward your friends and fellow travellers. And I’ll cheerfully allow as how this one’s the hardest: Lord knows I haven’t got it sussed in politics, say. You might boil it down to “Don’t eat your own,” but that’s a little tribal; you might mutter about dirty laundry and how it shouldn’t be washed in public, but that’s not really it, either. Flies and vinegar and honey, maybe? Oh, let’s take as a for instance a cartoonist like Jeff Parker: he’s got chops, he’s paid his dues in the storyboard mines, he’s done a book with adventure and super-powers and reviews that drop old skool names like Alex Toth. He’s an upstanding member of the tribe, is the point, and in the course of a recent interview he says something like this:

ST: What do you love/hate about the comic book industry?

JP: Let me begin with hate. (I love Peter Bagge’s Hate, by the way)

I get this symbolic image of a guy my age or older grabbing up superhero books from a shelf, with a little kid jumping around him trying to grab the books back. It’s an allegory of course, I’ve never seen this actually occur in a store. But there it is: my peers clinging madly to what they loved years ago, but now they’ve matured and want stories that explore relationships and heavier themes. Yet they can’t let go of the cape book, and the superheroes start killing each other and sleeping around, drinking, gambling, talking a whole lot … the kid has wandered off by now in search of something where good guys fight bad guys in a fun way. Back at the store, our adult has squeezed the bunnies to death. The moral? Give the kid his damned books back! Adolescent power fantasies are for powerless adolescents. Read a goddamned crime comic, or a romance book to meet those needs! We’re actually wondering why manga is doing so well now with kids? It’s pretty obvious—they’re writing to a young audience, using imagination and thinking about what would be fun. We can’t take any lessons from that? No, we look at it and think “hmmm the big eyes must be what they find appealing, or maybe these speedlines in the background …”

Give them back their books, and move on. Stop influencing what caped characters do. Stop having opinions on the X-Men. Our nostalgia gets credit for supporting the comics industry but what it really does is kill it. Pant, pant, wheeze ..

I forgot to mention something I love. I’ll come back to that.

And you’ve got two basic ways you can take this: on the one hand, you could say to yourself, you know, that Jeff, he’s one hell of a friend of the art. He’s a fellow-traveller—his love of adventure comics and storytelling and superheroes shines through. And he’s making a good point—there’s a dearth of kid-friendly comics, and avenues for getting those comics into the hands of kids, in the traditional American comics marketplace, or what’s left of it. Perhaps he’s being a bit hyperbolic—it’s more than possible to have a meaningful opinion on the X-Men; of course it is. But he’s mouthing off in an interview. Oh, sure, he could have made this point with greater clarity: “Stop having opinions about whether the X-Men should be wearing spandex again,” he might have said. Hindsight, bygones, l’esprit de l’escalier. His central image is colorful and telling; we can let him have it; we both, after all, have bigger fish to fry. (How does The Interman fit into Henley’s literature of ethics, say?)

Or! You could cry out, “A fool! I shall not suffer him gladly!” And then you could not suffer him with aggrieved asides and snarky commentary and then allow as how it was snarky commentary, really, but here’s why it was important, and before you know it, you’ve not only dissed your friends and fellow travellers, you’ve started complaining and explaining. Lady Montague sighs, and the hearts and minds are off after greener pastures. (Did you really think he was a fool? Did you really get any mileage out of claiming he was? For God’s sake, this isn’t Jonathan Lethem claiming he doesn’t write science fiction. Or Margaret Atwood, rather. Not anywhere near. And when in doubt, assume friend; we need all the friends we can get.) —Better luck next time.

(Why, yes. Of course these rules can be broken. All rules can be broken, if you know how, and when you’re done there’s no one left in a position to give a damn about how you broke the rules. —Yes, you can break that rule, too, of course you can. You know all this already.)

Third is simple enough: never open with a definition. (Or close with one, for that matter. Or stick one in the middle somewhere.) You’re here to describe, not prescribe; the critic’s mantra, to be repeated three times before ever taking up the pen, is “The map is not the thing mapped.” This isn’t rocket science: a genre, like superheroes, or a medium, like comics, has neither necessary nor sufficient conditions that can be limned in a few short, pithy words, to be folded up and tucked into your pocket. If the facts change, you must be prepared to change your mind. (There’s nothing sadder than a critic who can’t be surprised.) —Why, yes: I do know that Scott McCloud opened with a corker of a definition. But his (like everyone’s) is a special case: he was launching an entire critical enterprise, kickstarting a thousand thousand conversations like a mini-Big Bang; his definition (his attempt at a definition) was rather like Gödel going to Schrödinger’s liquor cabinet and opening it up to find out that the cat’s dead and his theory will never be complete, but so what—here’s that single malt he was looking for. Now the party can really get started. But even though he’s since backed sideways off from “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence” to, y’know, more of “a temporal map,” still, every young punk with a fast gun thinks they’ve made some telling point with every “yes, but” they can dredge up. (“Are your shoes comics?” I mean, really.) It gets old fast and it distracts from the real business we really ought to be about and frankly, it’s embarassing; best not to encourage them in the first place, and anyway, “Webster’s defines the thing I’m about to blow 800 words on as” is a rhetorical device best left to collegiate editorialists. Y’know?

—Your assignment, then, if you haven’t already, and should you choose to accept one from the likes of me: pick up a copy of Samuel Delany’s Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts and the Politics of the Paraliterary, so you can read “The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism.” It’s all about comics and writing about comics and genre and art and craft, and he’s much smarter than I am, so pay attention.

Auget largiendo.

Scott McCloud, cartoonist.

APE, 2004; we all went to Bucca di Beppo’s on Saturday night and sat at the Pope’s Table.

Further photos forthcoming. (Email me with any name errors or corrections, would yez?)

APE.

If you’re looking for me over the weekend, you’ll need to look in San Francisco. The Spouse and I will be attending APE: her to promote Dicebox, me to stand around looking at comics and try not to get in the way too much. There’s no particular table involved; we’ll be found more likely than not in the company of Patrick Farley or Lori Matsumoto or Kris Dresen or Madison Clell or Scott (or Ivy, or Winter, or Sky) McCloud or one or another of a variety of Pants Pressers, not to drop names or nothin.’ Plus, copious amounts of sushi will be eaten, and we’ll probably try to get to 826 Valencia Street again (this time, when it’s open), and there’s apparently a bookstore I need to visit, and we might even try to squeeze in a trip hereabouts, though I think all our evening meals are already spoken for, darn. Anyway.

Our new interviewing technique is unstoppable.

Ever wanted to ask David Rees a question? You know, the guy who does Get Your War On? (Among other things.) Comixpedia’s giving you the chance. Get in there and make it a good’un.

Or perhaps one would prefer—

Having filled you in on where I’ve been and what I’ve been up to, here’s what Jenn’s been busy whipping up: nifty preview pages for two new webcomics—Journal and Wode. Not as replacements for or competitors with Dicebox, Lord no. Just side projects to play around with while the big steam engine keeps chugging along. (You know, I’m starting to cop a clue as to why we haven’t seen much of each other lately—)

J. Bradford DeLong = minor god.

Oh, sure, he’s a daily must-read, and a great way for liberal arts dilettantes to come to vague grips with what it is they’re starting to figure out that they don’t know about economics, but did you know he’s also a fan of innovative webcomics?

Me neither.

(So if you haven’t plucked a BitPass card from the æther so you can plunk down an airy quarter for the privilege that is Part 3 of Patrick Farley’s Apocamon, hell. You have even less than no excuse, now.)

Successoratin’ Stan!

We’re in the home stretch of the overtime madness that is my day job, currently (should I provide a link? Oh, all right: a link), so what could be more appropriate than a slew of motivational goodies?

How about a slew of motivational goodies based on Marvel superheroes?

Here’s Elektra, the Greek ninjette:

EXCELLENCE

“Excellence is reserved for those who, even when they fail, do so by doing greatly, so that their place shall never be among those cold and timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat.”

How about her sometime paramour, Daredevil?

JUSTICE

“Justice is blind and has no fear. It is selfless, noble, and kind to all who serve it well, but know this… Do not dare justice, for it comes to all—right or wrong.”

Too wordy? Self-contradictory? Perhaps Wolverine’s trademark laconicism will get to the point (bub):

PERSEVERANCE

“Some people want it to happen… Some people wish it to happen… Others tear down the walls of resistance and make it happen.”

Or maybe not. (There’s also murderous vigilante Frank Castle, but perhaps the point is made?)

Luckily, Dirk Deppey also provides us with a link to the high-larious knockoffs. Which reminds one of the magisterially cheap shots scored by Despair.com, knocking off Successories, the éminence grise in this—field?—that Marvel’s knock-offs knock off, in their own unique, ah, idiom.