Descriptivate, don’t prescriptivate—

Damn skippy “conversate” is a word. It’s a beautiful word! Try it out in sentences instead of “converse.” Hear what it does to the rhythm. Snappy little backformation, that.

—What do you call it when you reverse-engineer a backformation? Because “opine” is the most godawful clunker of an admittedly useful word, and “opinionate” as a verb would sail so much more smoothly:

He opined that the New Deal was a cause, not a cure of the Great Depression.

He opinionated that the New Deal &c. &c.

See? Clarity and music. Makes what so many do just so much opinionation. —Which, well, icing on the lexeme.

“If indeed mankind came to earth for a specific reason, it certainly wasn’t to enjoy ourselves.”

I keep forgetting to mention how much I really really enjoyed this Zadie Smith essay on family and comedy.

But only if we can point to it.

“Architecture is by its very nature a specific form of science fiction: whether we’re using it to design luxury high-rises, modular refugee camps, solar towers, or complete urban ecotopias, architecture gives us the means, on par with literature and mythology, through which we can re-imagine the world.” —Geoff Manaugh, on Craig Hodgetts’ designs for Ecotopia

Mad, mad world.

“Mad”ness comes from the lazy epoch.

The aunt is mad at me.

The uncle comes home late.

The children are mad.

The dog is mad.

The housewife is mad at you—

the door is barred.

The ship is sunk, the crew

is mad.

—Ernst Herbeck [via; via]

Quisquiliæ.

Regrets: I regret leaving out Sara’s point from that “Comics Are Not Literature” panel about prose making you forget the black marks on the white paper, and Douglas’s complement that comics make you all too aware of these specific marks made by this specific person, and what that says about rough and smooth; I can’t believe I didn’t tie up the dangling loose end of “pretty much is good enough”; I wish I’d gone ahead and attacked the name of “graphic novel,” which is one of the main reasons why we’re all so het up about literature and not so much worried about art. (Aht?) There’s some nice comments over at the Valve, and I hope I wasn’t the last one in the pool. —Mostly I wish I hadn’t utterly missed the obvious joke of Canon and Continuity.

Let comics be comics.

To repeat: don’t think, but look!

My contribution to the Valve’s book event on Reading Comics! —I guess I had to wait until everybody else went to San Diego and Douglas won the Eisner before I could get it finished.

Much as any good fencer has studied his Agrippa, Douglas Wolk has read his Delany. —“My reply,” he says to his straw man,

is that I’m not going to define “comics” here, because if you have picked up this book and have not been spending the last century trapped inside a magic lantern, you already pretty much know what they are, and “pretty much” is good enough. That word I mentioned above that Samuel Delany coined, “paraliterary,” is part of a terrific essay called “The Politics of Paraliterary Criticism” that’s effectively scared me off trying to come up with a definition. If you try to draw a boundary that includes everything that counts as comics and excludes everything that doesn’t, two things happen: first, the medium always wriggles across that boundary, and second, whatever politics are implicit in the definition always boomerang on the definer.

That passage is from Chapter 1 of Reading Comics—a chapter titled, “What Comics Are And What They Aren’t.” —Now, this chapter no more attempts to delineate precisely what it is that comics is and isn’t than the book itself ends up plodding along the path implied by its subtitle: How Graphic Novels Work And What They Mean. But nonetheless and in spite of the wisdom of Delany, and the judicious scare he plants in the breasts of critics who study him, Wolk spends the first third of his book—a third that nearly everyone agrees is the weaker portion of the book, that is not so sharp or effective or enjoyable (though it is sharp enough, it effects, there is joy) as the rest, the two thirds in which he pulls this comic and that from the shelf and sits with you, reading them, see here, and now this, the very model of the modern descriptive critic—but the first third is spent laying out boundaries that if not the medium then at least that portion he’s setting aside to study in more detail yet manages to wriggle across; as he does so, he’s apologetically describing some of the boomerangs he’ll have to duck in the next paragraph. He knows the price he’ll pay for coming this close to defining comics, he’s told the straw man exactly what will happen, but nonetheless he does come just that close.

Why?

Come upstairs with me a minute.

We’re sitting on the couch, the Spouse and I. Dinner’s done; something is usually on the TV; past couple of days it’s been episodes of Burn Notice, which is cute; a Magnum, PI for the Buffy generation, and nobody told me how MacGyver it was, but we aren’t paying that much attention to it; we’re working. —Or at least she is. Her tray table’s cleared of dishes and leftovers, or maybe she’s hauled out the lapdesk; she’s spread out grimy sheets of 8½ x 11 recycled multi-use paper (30% Post-Consumer!), she’s got her pencils, and the kneaded eraser that Thurber likes to chew on, she’s got her ruler, and as for me? Well, my laptop’s in here, on the tray table in front of me, this essay begun in a Tex-Edit window, Camino up behind it with a dozen tabs open to this and this and this and this and this and this and this and this and this and this and this and this, I’ve got Delany and the McCloud trilogy and Wolk on the brass coffee table, and while she’s erasing ghostly figures and re-scoring panel borders and deftly tilting a head a bit more here, adjusting the angle of a hand (a gestural scribble, a soft grey curl with lines you can just make out are fingers) there, I’m—what?

Well, I’m not writing. —To write, I need to focus on the words words words, and I can’t when there’s words words words coming off the screen, getting all tangled up with the ones I want to put down. (Sometimes I can, but then I can’t tell you whether that was the one about the brother’s friend who’s tangled up with the Isræli arms-dealers or the one about the brother’s friend’s father whose daughter’s tangled up with the model scouts who ship white slaves to Dubaīy. —So why’s the TV on at all?) I end up sitting here distracted, feeling more than vaguely guilty since I’d promised the dam’ thing to John by the beginning of the week that’s almost already done, but something’s not clicking and I’m helplessly watching and listening, tangled up in words not my own, while she’s finished laying out this page and is on to the next, half an ear on the dialogue; half an eye turned up now and then for this scene or that.

All because I’m (ostensibly) writing, and she’s—well, she’s—

Dang it, what the heck is she doing?

Making comics, yes, but. She isn’t drawing. The drawing comes later, at the drafting table, on Bristol board and after, on the computer, in Photoshop. She isn’t writing. The writing came before, in bed, bits stuck in Google docs from time to time so I can look it over and say this ought to be hyphenated, that joke was pretty funny, and are you carrying this bit in the art? Because I have no idea what just happened. —She’s making comics, and what I want you to understand is that we do not have a word for what she’s doing.

We do not have a word for what she is.

Oh, for bits and pieces of it, sure. The writing. The drawing. You get into the world of industrial comics and you’ve got all sorts of words for all sorts of steps in the process: the writer, the penciller, the inker, the colorist, the letterer, the editor; heck, even with the “pencilling” you’ve sometimes got somebody who does the breakdowns or the layouts and somebody else who does the finishes, and somehow, somewhere in there, between the keyboard and the pencil and the ink, the comic gets made.

(It’s as if I could speak of the researching, the note-taking, the outlining, the typing or the handwriting, the editing and spell-checking, the typesetting, but not, you know, the thing I’m doing to make the essay. The writing. —Okay, maybe not so much with the editing.)

She doesn’t have a word for what she’s doing. —There is, I suppose, a word for what she is; a lot of people use it. Wolk uses it, himself, when he starts talking about the auteur theory, and what he terms “art” comics, which are so rarely the fruit of collaborations between this person who does the words, and that person who does the pictures, but are far more likely to be the work of one person who does the thing that’s both, and neither: a cartoonist. But this is a deeply flawed word, coming as it does from cartoon. “A drawing on stout paper made as a design for a painting of the same size to be executed in fresco or oil, or for a work in tapestry, mosaic, stained glass, or the like” is how it started, and to this day it carries an air of the preliminary, the unfinished, the ephemeral along with its more modern connotations of humor and exaggeration and caricature, its strong whiffs of the New Yorker and Saturday mornings. —One might note with delight the happy convergence with manga, the drawings made in spite of oneself, and to be sure Frank Miller’s characters are cartoons, yes—but is what he’s doing really cartooning? Is Eric Shanower really a cartoonist? How about Barry Windsor-Smith? Phœbe Glockner? Michael Wm. Kaluta? (Yes. We call them that. But.)

—Don’t think I’m some mad Quixote or Canute, about to unveil an ugly, awkward neologism. We go to criticize with the words we’ve got, and comics is itself as a medium hampered by its very name, comics: are they funny? What? —Our history is littered with the discarded banners of attempts to overturn the tyranny of that name for something else: sequential art, drawn books, comix, graphic novels—

Well. I might get to that one in a bit. —You go to criticize with the words you’ve got, so we’ll call her a cartoonist (a web cartoonist, to be more precise), for all that what she’s doing isn’t so much cartooning, and the end result isn’t cartoons, but comics. Just be aware that the words we’ve got for what’s going on are few, and deeply flawed, borrowed from other contexts and freighted with unwanted, unrealized connotations; that one of the most common terms for the people who do the thing we’re talking about trips us up with an unremarked elision of two of the more prominent ways one can divide those people into this group, or that: those who work in a deceptively simple style that communicates through exaggeration and even caricature—quite close to what we might all call without complaint “cartoons”—and those who work in a much more detailed, illustrative style, which might be termed deceptively mimetic—

Not to make too much of it. It’s the standard warning that ought to be engraved over every critical enterprise: “The map is not the thing mapped.” But in this case the map is even sketchier and more distortive than usual.

Another example:

Last year at San Diego, Douglas led a panel with a deliberately provocative title, “Comics Are Not Literature.” The following exchange ensued:

Dan Nadel

See, I don’t think of comics as reading.

Paul Tobin

You don’t think of comics as reading?

Sara Ryan

Ooh! Discuss!

Nadel

What’s the big deal? Why is that a big deal? Comics is about looking and reading. It’s not just reading. It’s a sort of dual process that you undertake. It’s a totally different process than reading a novel, and it’s different than watching a movie, so I guess I think of comics as a separate activity than reading.

Cecil Castellucci

It rests right next to the same place as reading.

Nadel

It’s a couple of doors down.

Castellucci

It’s definitely a kissing cousin of reading.

Tobin

To me that’s like saying that when I’m listening to you or Cecil talk, that I’m not listening the way I’m listening when I’m listening to music. You’re still listening, you’re still using the same—

Nadel

I don’t know, I don’t know. I guess I think of comics—it’s something else, it’s a different kind of process. I certainly don’t read Dan Clowes in the way I read, you know, Updike, or something. So it’s a different thing. You have to decode the picture—

Tobin

I don’t read Cecil Castellucci the same way I read Hemingway, either.

Castellucci

Thank God.

[…]

Nadel

I guess the reason I think it’s strange to talk about reading comics, or just to “read” art, or how the story makes you feel, is that to me it’s sort of, the most interesting comics—and you talk about this a little bit in your book—let’s take Gary Panter’s work, or Crumb’s work, or Herriman, or McKay, or Boody Rogers, or Fletcher Hanks, or, y’know, on and on and on and on and on. Cartoonists for whom the word and the picture are actually inseparable, you can’t take them apart—and also, create entire worlds on a page that you actually have to enter into, in the same way de Kooning creates a world on the canvas you have to enter into and explore in an entirely non-literary or reading-based way. It’s experiential. A different kind of thing entirely. I guess that’s why I think it’s funny just to talk about story all the time, because comics is so much more than story.

Tobin

I would argue that the combination of words and pictures in comics creates a narrative, and what I do with a narrative is I read it.

Nadel

See, I think of it as like you live in it, more than reading it, because I think like the marks on the page accumulate to so much more than reading. You have to decode.

Tobin

I know what you’re saying, that they make up something more, and that’s you reading it. That’s you perceiving and reading.

Nadel

I think it’s more just perceiving.

Wolk

Do you read a movie?

Tobin

…No. But I think you just threw that out. I think that’s completely unfair. I mean, I don’t read a baseball, either.

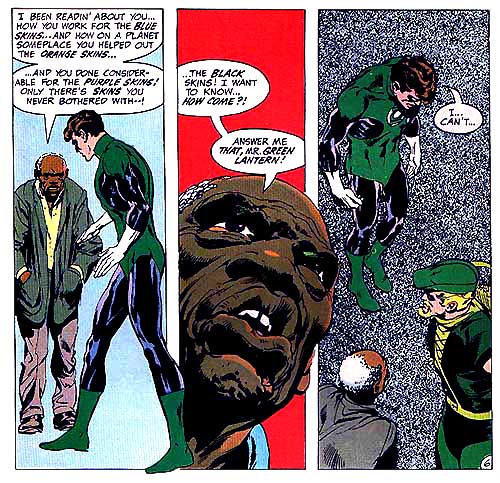

No, but you’d read a baseball game. Much the same way you’d read a movie, actually. —You do read movies, and you do read comics, but the point I want to make here is not that I disagree with the estimable Dan Nadel, or that I agree with Paul Tobin; nor do I want to start a humorous slapfest with our host John Holbo on whether comics are, y’know, a language or not. (They are. But.) —The point I want to make is that here we are at the beginning of the true golden age of comics, when one is no longer obliged to remind the mundanes that they aren’t just for kids anymore, when your average area man or woman has no difficulty embracing the concept that comics can be art just like writing or movies or music, here we are at the Summer Sundance, the Cannes for Fans, at a panel organized by the author of a volume of comics criticism entitled Reading Comics, here we are and yet people of good will who have studied this thing we call comics, who have lived with it to one degree or another in their personal and professional lives, these people (however provocatively) cannot agree on what to call the thing we do when we take in this thing we call comics.

Perhaps Nadel’s distaste for “reading” is as silly as mine for “cartoonist,” or all of ours historically for “comics.” Maybe. —But “reading” is an even more heavily freighted word, with so much hidden beneath the waterline that does immense amounts of work that you can’t see. Even if you’re used to using “read” as a semantic screwdriver, until you can read a movie or a baseball game (or even a baseball), still: it privileges the ordering and assembly of the various discrete bits into a (one hesitates to say “narrative” because oh my) whole; the act of looking, of perceiving, of appreciating those bits each on their own is left in the wake of a word like “reading.” —Listen a moment to Chris Ware’s complaint:

This is just an incredibly inefficient way to tell a story. It involved maybe 8 to 10 seconds of actual narrative time, but it took me three days to do it, of 12 hours a day. And I’m thinking any writer would go through this passage in eight minutes of work. And I think: Why am I doing this? Is the payoff to have the illusion of something actually happening before your eyes really worth it? I find it’s a constant struggle and a source of great pain for me, especially the last day when I’m inking the strip. I think, Why, why am I doing this? Whole years go by now that I can barely account for. I’m not even being facetious.

To read the comic is to see the illusion of something actually happening before your eyes; to go back and appreciate the fruit of three twelve-hour days is to—what? Look? Perceive? Read differently? —Whatever it is, it’s definitely a key component of comics, a thing we can do there and take advantage of nowhere else. “The most obvious sense,” says Wolk,

in which Watchmen is tethered to comics is the fact that it’s specifically about comics’ form and content and readers’ preconceptions of what happens in a comic book story. Beneath that surface, though, it relies on being a comic book for its crucial sense of time and chronology. The amount of time the reader has to spend working through the story isn’t the same as the amount of time the events in the story encompass—it’s longer—and the direction in which the reader experiences the story isn’t linear but keeps skipping backwards to revisit the past, as the narrative does.

Perhaps somebody at some point has read Watchmen straight through, but one of the joys of reading it is flipping back to see how images and scenes have been set up.

(Which aside from anything else it might have to say about reading and comics rather neatly encapsulates why I wasn’t looking forward to the movie even before I saw the ghastly preview.)

But: comics is hardly the only medium larded with semiotic landmines. Think of the dreadfully inappropriate name for the preëminent literary product of our times, the “novel”—which new thing has now been around for so terribly long that folks are worried it’s about to die of old age. —Quick! Define the novel in thirty-three words or less. (My own favorite attempt is Randall Jarrell’s: “A novel is a narrative of a certain length with something wrong with it.” And look! Comics are thus redeemed—they are graphic novels after all!) (But I get ahead of myself.) —Now: define poetry. (They do try.)

To turn to Delany, and the scare he plants in the breasts of the critics who’ve studied him, on the folly of definition:

Well, there is a certain order of objects—ones that the late sociologist Lucien Goldmann (in his brief book, Philosophy and the Human Sciences, Johnathan Cape, 1969) called “social objects”—that resist formal definition, i.e., we cannot locate the necessary and sufficient conditions that can describe them with any definitional rigor. Social objects are those that, instead of existing as a relatively limited number of material objects, exist rather as an unspecified number of recognition codes (functional descriptions, if you will) shared by an unlimited population, in which new and different examples are regularly produced. Genres, discourses, and genre collections are all social objects. And when a discourse (or genre collection, such as art) encourages, values, and privileges originality, creativity, variation, and change in its new examples, it should be self-evident why “definition” is an impossible task (since the object itself if it is healthy, is constantly developing and changing), even for someone who finds it difficult to follow the fine points.

And so we will never have a definition of comics, despite that opening salvo from Scott McCloud (“Juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence,” he says, and someone with a point says, “Well, what about the Far Side? Is that only a comic when it’s got multiple panels, and otherwise it’s something different than itself?” and someone without a point says, “What about my shoes? Are my shoes comics?” and we all roll our eyes)—in no small part because of the innovation inspired and encouraged by, among (many) others, Scott McCloud.

Damon Knight, speaking of the media-spanning genre of “science fiction,” which has had its own obsession with definition, rather famously said, “It will do us no particular harm if we remember that, like The Saturday Evening Post, it means what we point to when we say it.” —Of course, he said this in the context of a series of book review columns about science fiction; aimed at fellow science fiction enthusiasts whose knuckles may already have been bloodied in definitional battles over the term; when his editorial “we” points to something, it does so with an authority granted by people who already know who he is and what he does, who recognize his finger and the very fact that he is pointing, who are among the unlimited population that shares some of the necessary recognition codes; the men don’t know, but the little girls understand. —We do not define a novel before talking about the novel because we all know what a novel is; we can just point to it, even though we’d all disagree over the particulars. We can point to poetry and music and dance and architecture, ditto. And that “tiny geeky subculture” of a media-spanning genre has since the days of Damon Knight eaten the planet, indeed; we most of us have our zombie contingency plans in place; we can see the moving finger when it points.

But, with something like comics—

—and maybe you think you know what comics are, and what it looks like when Douglas Wolk points to it, but keep in mind the map is nearly blank; remember that we don’t have words for some the basic things we do when we make and read and re-read comics, and even if you think it doesn’t so much matter because you share the recognition codes, remember that there’s a hell of a lot of other people now suddenly interested in comics, or worried that maybe they have to pretend to like graphic novels, too; and remember that the superheroes are over here and the manga kids are over there and the indie all-stars are in that corner and God only knows where the webcomics end up, and even though there’s cross-pollination, still: you whoever you are do not share all the recognition codes; not even close—

—so Wolk spends the first third of his book (remember the Why? This was all an answer to that Why) sketching a history of the Yankee iteration of the medium that others will nitpick, and loops boundaries around “art” comics here and “mainstream” comics there that slip no matter how loosely they’re laid; he argues with a snarky Straw Man and lays out why he hates “his” culture (the culture of the comics fan, and not the music fan) and why he loves “his” culture, including his deliriously inclusive response to the hundred-things meme; he’s establishing not just his street cred with those of us who’ve maybe been around the block but don’t so much know this Wolk fellow, but also the street itself, for the day-trippers who might could be convinced to hang around for a while with the proper incentive. —Wolk does what he can to sweep clear some bit of common ground before kicking off into the other two-thirds of the book, which is neither a “best of” nor a “suggested reading” list, and certainly isn’t a canon, but does what Delany (and any of us, really) asks of contemporary criticism: brings “vision, history, belief, and the operationalism of the sciences” to bear on saying something about comics with “enthusiasm, grace, and insight.”

(This intractable uncertainty—this fundamental inability to properly name the thing we’re talking about, to even be sure, say, whether what we’re doing to that thing is “reading” or not—this is why I can’t help but sneer at unfortunate jokes like this:

(Hard sciences? Don’t make me laugh. Working with objectively measurable quanta is easy.)

But what is the thing Wolk’s saying about comics?

Last year at San Diego, Douglas led a panel with a deliberately provocative title, “Comics Are Not Literature,” in which he said the following:

There’s this really easy conflation to make, because both comics and books are printed on paper and they’re bound and they have spines, and they’re in book form, and they’re sold in the same places, and they’re in libraries, but there’s a real distinction between them, and I’ve seen things—there are projects now, where there are companies that are soliciting scripts for graphic novels from established prose writers, and they will have no idea who’s going to draw them, oh, doesn’t matter, somebody can just make the pictures. They’re all going to suck, people! They’re all going to suck!

(This year, he gave a talk entitled “Against a Canon of Comics.” Anybody got a transcript?) —To so completely identify comics and prose because of some similar underlying techniques and some accidents of technology and marketing is to risk overwhelming your nascent understanding of what comics is and can do with everything you already know about what prose is and can do; to erect a canon with such overwhelmed understanding is to elevate those comics closest to your idea of what makes prose good, and risk leaving out those comics that are closer to anyone’s idea of what makes comics good. (And, of course, the reverse: to so completely identify comics and film or fine arts etc.) —Scott McCloud tells a little parable about it, in Understanding Comics. The two halves of his dialectic are Artie, the artist, and Rita, the writer, and they’re determined to come together to make the best comics ever—

To privilege the writing by focusing one’s expectations on that which makes good prose, to privilege art by focusing on that which makes good imagery, is to risk tearing comics away from whatever it is that makes good comics—the thing that happens in the gutter, as it were. (Of course, McCloud’s parable in turn privileges his ideas regarding the power and immediacy of cartooning over illustrative, mimetic work, which, well, I mean, um.)

—It’s simple enough, but astonishingly easy to forget, lose sight of, fail to keep in mind: we must let comics be comics. Simple enough, but because our ways of making and reading and doing and letting comics be are all so tied up in other things, other media, other habits, because we must beg and borrow and steal the freighted words we need to talk about the things that are so clearly there, on the paper, it’s harder than it seems.

For years, comics were junk, were trash, were just for the kids they couldn’t help but corrupt; they were paraliterary—of “those written genres traditionally excluded by the limited, value-bound meaning of ‘literature’ and ‘literary’,” to quote Delany. —“Maus is not a comic book,” as that infamous early review is said to have asserted, but as another contemporary review had said, Spiegelman used “all the quack-quack wacko comic strip conventions with the thoroughness and enthusiasm of a connoisseur.” And won a Pulitzer! There must be something there. —And so, slowly, as more and more critics and newspaper book reviewers turned to writing about comics, the following headline over the next twenty years ossified into something beyond cliché (say it with me, now): “Bang! Zowie! Comics Aren’t Just For Kids Anymore!”

Twenty years it took to sink in.

And now it’s not that the tyranny of literature and the paraliterary has been overturned; that will always be with us. And it’s not that comics have as a whole been redeemed to the limited, value-bound meaning of “literature” and “literary.” It’s that comics—no longer just for kids—is now at last provisionally among that set of media which might have this or that of its works judged as “literature” or, of course, “art.” But those works—those graphic novels and fine art pieces—are being judged on hopelessly muddled merits. —Reading Comics is sold as a “canon-smashing book” not because there is a canon of comics to smash, but because any canons that might be made for comics now would be wrong, would be broken, would lean too much this way toward the prose or that toward the art or back and back with the backlash against elitism and snobbery—and canons are harder to change even than the habits of headline writers. Instead, let comics be comics for a while, and let us read them and look at them and write about them, describing them wherever and however we find them. Let comics be comics, whatever that might end up being.

That we will never know enough to make a proper canon is, of course, the point. —All we can ever do is point to the thing we’re talking about. There’s only so much common ground you can expect.

Hope is the new bleak.

Every now and then

A madman’s bound to come along.

Doesn’t stop the story—

Story’s pretty strong.

Doesn’t change the song.

While back, Kugelmass wrote about an “indispensable essay” by Sean McCann and Michael Szalay called “Do You Believe in Magic?”—and while I haven’t gotten around yet to reading it myself, this passage of Kugelmass’ stuck with me:

While McCann and Szalay criticize academics who believe in the political efficacy of their symbolic labors, I would argue that most scholars working on culture now invoke “the political” in bad faith, with little hope of creating real change, out of a desire to seem compassionate and politically involved to hiring committees and their peers. The proof is in the pessimism: the message is that political change is impossible, even if an awareness of injustice is still praiseworthy.

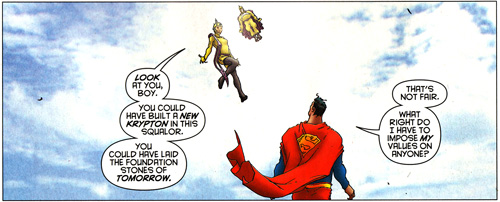

Mostly because it reminded me of nothing so much as this:

That’s from Runaways, which is about the best set of characters to be added to the Marvel universe in thirty years—and I can say that not because it’s a good comic book about compelling characters, but because so few new characters are ever added to anything like a Marvel universe (instead, we work endless shifts in the nostalgia mines, coming back to the past a bully again and again to eat our own four-color fictions, yes yes). —The Marvel universe centers around a New York City riddled with superheroes, from the Avengers up on Fifth to the Fantastic Four in midtown to the X-Men out in Westchester; Brian K. Vaughn drops us instead in Los Angeles, where a group of kids discovers their parents are actually supervillains, working together to control the city and its crime. (Vaughn uses the Gothamite myopia of 417 5th Avenue to good effect: the reason LA’s been so quiet in the 616, home until now to nothing more superheroic than the West Coast Avengers and Wonder Man, is that these supervillans are so damn good at what they do: their fist is adamantium; its grip implacable.) —The kids, of course, do what anyone would do, upon discovering their parents are evil: they run away from home, learn to use their powers and gifts, and come back to fight the good fight, defeat their parents, and—homeless, jobless, hunted—squat in a cave under the La Brea Tar Pits, using their powers and gifts to, y’know, fight supercrime and stuff. (And help other runaways, of course, like the android son of Ultron, or the Super-Skrull above, who’s run away from penn’s people’s genocidal war.)

That is, of course, what you call high concept, and to my mind works much better than Vaughn’s other, better-known comic-book pitch.

After all, what heroes these kids are! Homeless, jobless, hunted, still: they don’t try to change the world about them. Much as they might want to. They use their powers and gifts, their superstrength and supertech and supermagic and their telepathic velociraptor instead for good, to keep the world about them safe as it is. —An awareness of injustice is all well and good, you see. But political change is impossible. Only villains try to change the world.

This is how it works in the superhero business, of course; the story that’s pretty strong. —And in part it’s commercial necessity, sure: superheroes live in something very much like our world, except with superpeople, and they have to come back month after month for another 22 pages of four-color adventure; if they went about trying to change the world, well: pretty soon their world wouldn’t look very much like our world, would it? What with all those superpeople in it, with all that great power.

But it’s also what’s bred in the superhero’s bones: that great power lies hidden until some threat springs up—and then the glasses come off, the shirt’s ripped open, the power’s unleashed. Once the threat’s vanquished, the power retreats; our hero’s alter ego stands up, brushes away some debris, resettles the glasses, and no one’s ever the wiser that they were saved by the great cloaked power that walks among them every day. —If you start to use that power not just to save the world from threats but to change it, make it better—well. You’d be out there all the time. You’d never wear the glasses again. They’d start to catch on.

A great responsibility comes with that great power, after all, to do the right thing. But what is the right thing? (You think you know? Really? Who are you, God?) —Best to swear your own Hippocratic Oath before pulling on the longjohns: First, make no change. “Because traditional superhero teams always put the flag back on top of the White House, don’t they?” said Grant Morrison back in the year 2000. They were writing an introduction to the first collection of Ellis and Hitch’s Authority. “They always dust down the statues and repair the highways and everything ends up just the way it was before…”

Morrison would have you believe (for the length of the intro, anyway) that Ellis and Hitch invented the idea of uncompromising superheroes who set out to change the world like the best of proper villains: “The Authority dares to imagine a world beyond the post-modern ironic hopelessness of endless recycled TV quotes and retro-nostalgic feedback. Welcome to a superteam with an agenda, on a scale beyond the billion-dollar budgets. A superteam whose headquarters looks like a dog’s nose and still kicks ass.” —It’s bollocks, of course, and only forgivable because Morrison clearly knows it’s bollocks. Superheroes have in one way or another been bucking against this static stricture for years, ever since the writers and artists and editors started to suss out that, y’know, they had this great power, right? Maybe a great responsibility went along with it?

They’ve been bucking at it, but they haven’t overturned it. The story’s pretty strong. Heroes defend the status quo. It’s what they do; it’s what makes them heroes. The Authority, who do not, end up as despotic demigods (with much less grace than Miracleman before them), and even from the start it isn’t so much a superhero comic as it is a noisy widescreen smashemup comic. —A much better high concept from Ellis is Planetary, where a villainous Fantastic Four defend a status quo that hoards the wonders promised by pulp fiction, keeping them out of the hands of the rest of us all; the righteous rage of the protagonists as they set about the task of returning our birthright is a splendid little engine of subversion. (Even better is his Global Frequency, in which cast-off Cold Warriors cobble together a DIY network of cellphones and satellites and Q-clearance secrets: mad scientists and retired superspies walking among us, keeping us safe from the pocket armageddim they helped to build back in the day for bosses who no longer have the budgets to keep them in check. Great cloaked power with a crippling responsibility fighting horrific threats—but threats to a hopeful new status quo, threats engendered by the overturned vestiges of the last status quo, still kicking out there in the dark.)

—Awareness of injustice is praiseworthy. Hell, it’s necessary: how else are you going to know whom to hit?

But political change: that’s impossible.

Turn back to that scene from Runaways, and that Kugelmass post:

The rainbow-colored girl is Karolina, who goes by Lucy in the Sky; she’s an alien whose parents hid in LA as movie stars and used their alien abilities to get ahead in the Pride. The one doing the fade from Jay-Z to Beyoncé is Xavin, the aforementioned Super-Skrull. —Xavin shows up after the Runaways defeat their evil parents and claims Karolina as his bride. The usual punchemup is followed by the usual expository dump: a long-ago agreement between their parents arranged a marriage between them, Xavin’s here to make good on it, and stop a terrible war between their peoples. But! Karolina’s gay.

“I… I like girls,” she says, outing herself for the first time to most of her team.

“Is that all that’s stopping you?” says Xavin. “Karolina, Skrulls are shapeshifters.” (It’s true. They are, and penn promptly shifts from Beast to Beauty.) “For us, changing gender… is no different than changing hair color.”

—Xavin has since spent most of the rest of the comic in male form, and while there’s tonnes of interesting possibilities there, ways to address sexuality and appearance and transgender issues, the reality is we’re dealing with the midlevel properties of a company that’s just now getting used to the idea of admitting the very existence of gays and lesbians in their proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fiction. What we’re dealing with is a token gay character in a relationship that to every external indication is perfectly heteronormative. —Runaways is about to get a new creative team; “Xavin won’t be a girl skrull,” the artist has said; “editorial make a note on that already, that one will change completely.”

Some critical theorists try to avoid sounding corny or naïve by exiling their political optimism to a purely theoretical or ineffable realm, a move McCann and Szalay lampoon as “The art of the impossible.” To take one example, in uncomplicatedly’s excellent new post there is a description of the queer theory version of this:

This was particularly true of the queer theorists, at least two of whom focused on queer reading practice as something that draws on textual possibilities rather than textual actualities to move toward an imagined utopian future that is acknowledged as imagined, and yet still must be imagined.

Well, Christ. I mean really. Can you blame them?

But to circle around again to whatever I thought my point was going to be when I got started (and I still haven’t put in anything about fear of power as political change is impossible so therefore the power to effect it must be impossibly great and the accompanying responsibility too too much to bear please take it from me please, and we could even hare off after learned helplessness if we wanted to: all the things that keep our superheroes reactive, stammeringly inadequate in the face of simple, pointed questions from those on the short end of the stick: status quo)—

Dr. Horrible, of course. Who’s talking about anything else? —“Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog” is Joss Whedon’s barn-raising internet show, a musical about a bumbling supervillain who’s trying to win the girl of his dreams from a smugly thuggish superhero. The supervillain is, of course, the protagonist, and so must win our sympathies; right at the very beginning of his first blog, he speaks a little speech to let us know what kind of supervillain he is:

And by the way, it’s not about making money, it’s about taking money. Destroying the status quo. Because the status is not quo. The world is a mess, and I just need to rule it.

He’s holding a plastic bag filled with the remains of the gold bar he tried to teleport out of a bank vault. “Smells like cumin,” he says, and sets it to one side—bumbling, like we said—but our hearts are with him. The world is a mess. We do not want the status quo. The smugly entitled heroes who defend it are not on our side.

We are all supervillains, now.

(Actually, our hearts are with him from his opening laugh, but that doesn’t help my argument. So.)

—This, by the way, is the secret of IOKIYAR; this is how it is that a Republican can shred the Fourth Amendment by resuming the warrantless wiretaps of yore, take up the Nixonian argument that it’s not illegal if the president does it, and blithely overturn the Magna Carta itself, and hear nothing but applause—yet if a Democrat but mentions a “civilian national security force,” the applause turns to jeers of brownshirts. —Republicans are conservatives; conservatives defend the status quo, standing athwart history yelling “Stop!” at every threat that comes along; those who defend the status quo are heroes—says so on the label. And we will always cut heroes more slack than villains.

(We are villains. We want to change the world. We demand, for instance, that we must all work together to change our collective behavior to offset the upset of global warming. —And it’s villains who demand we change the world; villains who demand we work together are fascists. QED.)

So we can’t change the world, political change is impossible, but we can change the story, right? A little? Change if not the status quo, then change the direction that phrase is pointing? And once we do that—

Well, yes, and no. You have to know where it’s pointing, first. “Dr. Horrible’s” isn’t a story about changing the world. That’s just a gesture towards audience sympathy which proves mildly interesting in the current political climate. “Dr. Horrible’s” is a story about a bumbling supervillain who’s trying to win the girl of his dreams from a smugly thuggish superhero. Dr. Horrible isn’t a world-shaking agent of change, out to slyly subvert our received sense of right and wrong; he’s upset that this girl he likes but can’t talk to is sleeping with this utter jerk who will never treat her right—

Dr. Horrible is a Nice Guy.™

For me, the most chilling moment in the whole thing comes at the beginning of Act II, during the duet between Horrible and Penny (the only person who does a damn thing to effect any political change at all)—it’s when Dr. Horrible, spying on a date between Penny and Captain Hammer, sings:

Anyone with half a brain

Could spend their whole life howling in pain

’Cause the dark is everywhere

And Penny doesn’t seem to care

That soon the dark in me is all that will remain

—Jesus, I thought. Does Whedon know what he’s playing with, here? The moment passes under Penny’s wispily soaring lines about how happy she is, how can she trust her eyes—does he see how twisted the responsibility just got in that seemingly tossed-off stanza, the status quo that’s been set up? —Yes. Yes, he does, and in the end, as Dr. Horrible takes his wrongful place in the Evil League of Evil, a bumbler no more, his only saving grace, his sliver of a chance at redemption, is he can finally see it, too.

Awareness of injustice is praiseworthy. Political change? Impossible. We can’t possibly change the world. Not without changing the story, first.

And if you’re going to do that, you’d damn well better be sure just what story it is you’re in.

Now, as to Reading Comics—

Two paths, a yellow wood: divergence!

Timothy Burke is first out of the gate with a reading of Reading Comics, and while I’m still frowning over my own opening lines I wanted to say: yes, the Comics Journal and Scott McCloud and, yes, even Douglas Wolk each in their own way suffers, to this degree, or that, from a need to redeem comics post-panic to mainstream or academic respectability—but damn do they ever go about it in very, terribly different ways. —Such that umbrelling them all beneath a single shibbolethic “Comics Journal Syndrome” left me quite dizzy.

Always already.

One Million is partially a discrete story and partially a corporate directive: a coordinated event involving the work of dozens of DC’s artists and writers for hire, but with core concepts created by Grant Morrison, who with Val Semeiks and Prentiss Rollins generated the four-issue miniseries in which the main story events occur. Morrison’s work stands out for considering the DC Universe’s structure from a critical perspective, and in One Million he presents a vision of the future that, as an extrapolation, highlights the unspoken paradoxes of the DC Universe as an ecology for intellectual property more than it does the rules of cause and effect that ostensibly govern the universe as a serial fiction. One of the members of the Justice League asks logically, “What are the chances of an identical JLA arising hundreds of centuries from now?”; the degree of similarity between this future of the DC Universe and its present seems a stretch even within the loose reality of superheroes, and yet, given the real rules of the DC Universe—Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman must maintain the iconicity, the brand equity, that makes them viable in a market—it makes perfect sense that, within the parameters of this corporate fiction, the year 85,271 will bring us more of the same Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman.

We went to Douglas’s house for the Fourth; well, Douglas’s and Lisa’s and Sterling’s. There were some comics people there, and some people who weren’t comics people, but there were enough comics people there that we talked a bit about comics. (There was a music person or two there as well, and we also talked about music, but everyone can talk about music.) —Douglas was passing around the first issue of Mike Kunkel’s Billy Batson and the Magic of Shazam!, soliciting reactions (consensus: why did he have to credit himself with words and pictures and heart?) (though I thought but didn’t say: Open Season!); this prompted one of the people who weren’t comics people to ask which Captain Marvel this was.

“DC’s got him,” someone said.

“Yeah, but this is following pretty closely on Jeff Smith’s take,” said someone else.

“So it’s in Jeff Smith continuity?” said a third person, disingenuously.

“Well, there are fifty-two universes in the DC universe now,” I said, only a tad less disingenuously. “So who knows?”

“Exactly fifty-two?” said the person who wasn’t a comics person.

“Yes,” said Douglas, with that smile of his. This is so ridiculously geeky; this is so ridiculously cool.

“Except one was destroyed, right?” I said.

“In fact, it was the fifty-first that was destroyed,” said Douglas. “So now it goes one through fifty and fifty-two.” —They hang like fruit from the Multiversal Orrery, green and blue and cloud-frosted: “New Earth is secure,” says the super-science guy in his super-science car. “The Bleed drains are intact. The Multiversal Orrery has survived repair after the loss of moving part: Universe 51.” (It is all so much bigger than we even imagine, yet look! The Earth is still the most important place of all. How comforting!)

“So, are we in there somewhere?” said a different person who wasn’t a comics person.

“Not anymore,” said Douglas.

“To them,” I said, “we’re fictional.” I hadn’t known we weren’t in there anymore. I’m thinking of fiction suits.

“Well, actually, not exactly,” said Douglas, his smile widening. “In All-Star Superman 10, Superman jumpstarts the infant universe Qwewq to see what a world without superheroes would be like. And it’s us. He created us. Superman is basically God.” —And it’s true; he did, almost as an afterthought, with a nano-optical transfusion of pure solar energy. And it’s us. There at the end we see Earth-Q, inside the barely beating heart of the sickly infant universe Qwewq, and there’s Joe Shuster, drawing Action Comics #1: “I really think this is it… Third time lucky. This is the one… this is going to change everything.” (As above, so below, yes yes, which leaves only one question: what’s up?)

“Wouldn’t it make more sense if his father was God and he sent Superman to save us?” said the person who wasn’t a comics person.

“Well,” Douglas started to say, but I hadn’t been paying attention; I was trying not to think of Chris Ware, so I interrupted. I said, “Wait a minute. Didn’t they send that superteam into Qwewq to save it from not having superheroes?” [JLA: Classified 1 – 3. —Ed.]

“The Ultramarines,” said Douglas. “Yes.”

“So if we’re Qwewq, then where are they?” I said, spreading my hands to take us all in. “Because they sure aren’t here.” (“A doomed micro-Earth, in an infant universe,” says the Knight. “With no such thing as superheroes,” says Jack O’Lantern. “This should be interesting…” says Warmaker One.)

“Ah,” said Douglas. “They aren’t here yet.”

In Molho’s bookshop, one of the few downtown reminders of earlier times, I found Joseph Nehama’s magisterial Histoire de Israélites de Salonique, and began to see what an extraordinary story it had been. The arrival of the Iberian Jews after their expulsion from Spain, Salonica’s emergence as a renowned centre of rabbinical learning, the disruption caused by the most famous False Messiah of the seventeenth century, Sabbetai Zevi, and the persistent faith of his followers, who followed him even after his conversion to Islam, formed part of a fascinating and little-known history unparalleled in Europe. Enjoying the favour of the sultans, the Jews, as the Ottoman traveller Evliya Chelebi noted, called the city “our Salonica”—a place where, in addition to Turkish, Greek and Bulgarian, most of the inhabitants “know the Jewish tongue because day and night they are in contact with, and conduct business with Jews.”

Yet as I supplemented my knowledge of the Greek metropolis with books and articles on its Jewish past, and tried to reconcile what I knew of the home of Saint Dimitrios—“the Orthodox City”—with the Sefardic “Mother of Israel,” it seemed to me that these two histories—the Greek and the Jewish—did not so much complement one another as pass each other by. I had noticed how seldom standard Greek accounts of the city referred to the Jews. An official tome from 1962 which had been published to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of its capture from the Turks contained almost no mention of them at all; the subject had been regarded as taboo by the politicians masterminding the celebrations. This reticence reflected what the author Elias Petropoulos excoriated as “the ideology of the barbarian neo-Greek bourgeoisie,” for whom the city “has always been Greek.” But at the same time, most Jewish scholars were just as exclusive as their Greek counterparts: their imagined city was as empty of Christians as the other was of Jews.

As for the Muslims, who had ruled Salonica from 1430 to 1912, they were more or less absent from both.

If they aren’t here yet, well, that does resolve a few things, I suppose, such as how the Knight and Beryl, his Squire, can show up a year and a half later on the island of Jonathan Mayhew, and how Superman inspires Earth-Q after the Justice League chases Black Death into it and gets lost. (“As unlikely as it seems,” he says, “this unhealthy attoscopic copy of Earth developed entirely without superheroes.” —Superman isn’t usually one to lie behind the passive voice.) —But keep in mind there are two Qwewqs in that story: the infant universe, over immensely unthinkable gobs of time, grows up into the adult universe of Qwewq, tainted by a seed of evil planted long ago now by Black Death, and despondent at having grown up for so very long without superheroes of its own, it comes back in time to attack the Justice League even as they’re lost inside its infant self: it becomes Neh-Buh-Loh, the Nebula Man, whose touch has the power of 20 atomic bombs. (We become; attoscopically small though we may be, in an unimaginably large universe the size of a big man, we are nonetheless the most important thing of all. We come back in time, despondent, tainted; it didn’t change everything, after all.)

And we know what happens to Neh-Buh-Loh, dark Huntsman to the Queen of the Sheda, who comes back in time over and over again from the far future at the end of it all to stripmine civilization whenever it gets rich and ripe enough; she ate the age of Neandertal super-science, destroyed the glory that was Camelot, and came for us here at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the apotheosis of the superheroes—well, not us, no, but New Earth or Earth-1 or wherever it is in the Orrery where the superheroes live. Neh-Buh-Loh was tasked with killing the Queen’s daughter before they invade, but he couldn’t; he hid her, instead, and for failing his dark Queen he was exiled to the Himalayas. Frankenstein (née Frankenstein’s monster) finds him there and kills him. —In a corner of the data readout Frankenstein downloads from SHADE we learn that the effort of the Ultramarines has been considered unsuccessful; given superheroes, we grew up despondent anyway, came back still tainted. (Everything still wasn’t changed.) —“They could not heal you,” says Frankenstein, hauling Neh-Buh-Loh’s lance from his own dam’ body. “Instead they gave you medicine to hasten your end. The flaw… the doubt you feel… is the presence of death…”

That’s us, then, Earth-Q, the world the superheroes couldn’t save in the barely beating heart of an infant universe: disgraced, despondent, tainted, unchanged after all, come back a bully to eat our own four-color fictions, only to die writhing in the snow by the monstrous hand of Frankenstein.

So can you understand why I’d rather believe the superheroes haven’t gotten here yet? (Look about you! Do you see them anywhere yourself?) —Of course, Neh-Buh-Loh does say he’s only three billion years old when Frankenstein kills him, and we’ve been around some five times longer than that. (Well. Not us, per se.) And All-Star Superman is in Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely continuity; it doesn’t exactly hang from the Orrery with all the fifty other universes, and we have to turn to hypertime and the snowflake to begin to make sense of that. —I have been a bit disingenuous.

All this muddle and hullabaloo roils just under the smoothly buffed surface of those corporate icons. They tried to iron it all out back in ’85 with Crisis on Infinite Earths: fix those nagging continuity errors by wiping them out; rewrite history to simplify it all: top all the Silver Age Crises on Earth-Two and Earth-Three with the Crisis to end all Crises: Infinite Earths! Monitor vs. Anti-Monitor in the battle to end all battles! Smash them all together in a super-genocide that leaves us with but one clear agreed-upon continuity, and start the universe all over again from there. A Big Crunch, that spawned the next Big Bang; and so we returned and began again.

But for all its noise and exuberance and color, its sound and fury, this is still a humble, ephemeral art; there is more than a little wabi-sabi in comics, and there is always already a flaw in continuity. And as a small army of cooks sets to writing and penciling and editing their multitude of bubbling broth-pots, that flaw begets more flaws, swarming and roiling about, and the attempts to work around them become more baroque until elseworlds and otherwhens hive themselves off what you now must call Earth-Prime, many worlds that offend the sensibilities of continuity’s Copenhagen-cops (what an easy way out, they sniff). And here we are, back where we started: now it’s an Infinite Crisis to top the Crisis on Infinite Earths, only when we’re done, it’s not that there’s one Earth again, but fifty-two, hanging from the Multiversal Orrery. (Except, you know, the All-Star books, and a bunch of the Elseworlds stuff, and some of the future stuff, all of which is in hypertime, or out on the snowflake elsewhere, which we don’t really talk about much, but anyway—)

Having already had a crisis, though, and kept going, you’ve always already had that crisis. Much as they might like to forget it, later. —Have another, or enough of them, and you’ll find you’re always already in a crisis. The fifty-two Earths were hung from the Orrery only a couple of years ago, and already they’re threatened by the Final Crisis (as final, I’m sure, as its predecessors were infinite). —“Do you feel as though time is speeding up, darling?” says Lord Fanny, somewhere out there in hypertime. “I mean, actually getting faster.”

And there’s already a flaw, as always: this Final Crisis was to have been precipitated by the deaths of the New Gods, and Orion, Darkseid’s son, raised by the Highfather, the bestial, well-meaning New God of war, is killed a couple of different times in a couple of different ways in a couple of different places by different writers and artists each keeping watch over their different pots of broth, all before his body can be found in the garbage in the opening pages of the Crisis itself. —As flaws go, this one’s simple enough to explain away: cowards, after all, die a thousand deaths! How many more might a god die? I’m much more concerned about that Gordian knot I kicked around above: the infant universe Qwewq, and us, left alone on Earth-Q: created by Superman after he found it, already abandoned by the Ultramarines who hadn’t left yet to save us from despondency, murdered by Frankenstein some twelve billion years before we have a chance even to show up. (Some fans complain how Superman in Final Crisis didn’t seem to know Orion, or the New Gods, when after all he’s served with them off and on for years; how much worse not to have recognized Earth-Q when he walked its streets a couple of years ago!) —And that tangle of inconsistencies all came not from a dozen different broth-pots and a dozen different cooks but just the one writer, Grant Morrison, who’s busily upending the Multiversal Orrery with its absolute honest f’reals this time Final Crisis.

And who is always already up to something. —Even if it isn’t always the same thing.

That went on a bit longer than I anticipated. —Most of this we didn’t talk about at all; most of it only occurred to me later. Exegesis d’escalier. And we didn’t only talk about comics, either. Lisa and I, for instance, had a long conversation in the kitchen about infants and kids and the limen between them, and the strange nature of the year that stretches before me and the Spouse and which overwhelms just about everything else these days. And I snagged a CD by Princess Superstar from Douglas’s freebie box. It was a good party.

Mostly I wanted to set up the punchline: it’s this thing I can’t find anymore on the web, since Jason Craft left and went to Earth X and then let Earth X fall off the web and then brought it back. He had a line in documenting the care and feeding of what he called proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fictions—soap operas and arc-driven television, MMORPGs, the superhero multiverses of Marvel and DC, which are arguably the largest and most sophisticated of them all.

He wrote a brief squib in his long-lost blog, about something a friend of his said, when asked why he bought all those comics every month. Are they really that good? Are they any good at all?

Well, yes, they are any good at all, his friend said to this interlocutor. (Friend of a friend of a guy I’ve read on the internet whose blog I’m citing has gone the way of all æther.) But are they that good? See, and he hemmed and hawed a minute, as anybody would who’s spending that much money every month on ephemerally exciting attempts to maintain the iconicity, the brand equity that makes superheroes viable in the marketplace. And then he said, it’s like, you know, all this stuff is happening, right? I mean, sure, in comic books, yeah, but it’s happening there, and this is how I keep up. It’s like I’m reading the news, you know? Is the news that good?

Then you’ll look over that day, rewrite Dallas.

Because JR was too evil,

He was too evil.

It’s all because of JR that everything

Went crazy with the world,

With the world.

Make JR nice and all our history

Will be mystery.

Remember:

This song could be about Jesus

But it can also be a song about you.

This song could be about Jesus

But it can also be a song about you.

Be good

Do all the things you should

Be good

Do it as you wish you would

Be good

Do all the things you should

A nightmare from which etc.

Also, I’d like to join my wingnut brethren in demanding to know why Google insists on slighting Western civilization everywhere by not honoring Bloomsday with one of those special little squiggly cartoon things. (Is a stately plump Buck Milligan too much to ask?)

Any sufficiently advanced art is indistinguishable from poetry.

From Norway via Mr. Snead, One Foot in the Wild—an RPG poem on nature and footwear. (Perhaps “indistinguishable” isn’t quite right—?)

Der Tod und das Mädchen.

Heather Corinna insouciantly tosses a head-slapper of an analogy into the sex-work debate.

Say nothing.

Sara reminded me of rickrolling, and got me to read the Wikipedia article, and—well, there’s just something about the po-faced seriousness of Wikipedia’s house style, you know?

In the “Never Gonna Give You Up” music video, directed by Simon West, a smiling Astley sings and dances to the song in various outfits and venues, sometimes accompanied by backup dancers. A bartender has a notable presence in the video, as his behavior gradually shifts from casually noticing Astley’s singing to being fully engrossed in the song with energetic acrobatic moves. The athletic exertion of many of the other dancers also becomes more intense over the course of Astley’s performance.

You’ve got to say something, but you can’t say something, or you’ll risk unleashing controversy—we assume, for the moment, that your goal isn’t to launch a flame war—and so you bend over backwards to say something about the thing in question without saying anything until that last sentence topples down a Zen navel of staggering uselessness, utterly indistinguishable from its hypothetical Onion parody.

I’d just gotten out of the shower, trying to sluice off the Bakersfield dust, and I stood there before the hotel TV set with the remote in my hand, gawping as the talking head said something like how unfair it was, how he couldn’t get over how unfair it was, that a white politician couldn’t survive something like this. This being Obama’s relationship with the storied Reverend Wright, his unfair survival of which has been only by dint of writing and delivering one of the most powerful speeches in the last, what, 40 years of American rhetoric? Can we make that call yet?

Thing being that it seems the talking head is blithely unaware of white politician John McCain’s relationships with snarlingly vicious anti-American Christianists such as John Hagee and Rod Parsley, that he’s managed to survive by dint of inviting the press corps to a barbecue at his wife’s summer house.

So I yelled at the TV and changed the channel. Alton Brown was showing us how to cook an omelette. —It was only later that it occurred to me: maybe when I was walking through the lobby and saw a giant TV screen full of TV screens full of pictures of Wolf Blitzer standing there, mildly puzzled, before a rank of giant TV screens in his glossy, empty Situation Room; or maybe it was while I was sitting in the Salt Lake City airport and some white-toothed boytoy surrounded by bobbing glossy headshots boasted about sending his Entertainment Tonight Truth Squad out on the thankless task of determining whether Will Smith was really a Scientologist now or what—the talking head had time to fill. He had to say something about the thing in question, but he couldn’t risk saying anything, and so.

…his behavior gradually shifts from casually noticing Astley’s singing to being fully engrossed in the song with energetic acrobatic moves.

It’ll help, I think, keeping this in mind. Whenever they say something stupid (which is, um), they’re just doing their job, which is to say something about the athletic exertions of the background dancers without saying anything at all.

—I’ll smile more, anyway, and yell less, which is as good as it gets these days.

As falls Duckburg, so falls Duckburg Falls.

I don’t know why it should be so affecting to pick up an English translation of a 37-year-old Chilean book on Disney comics hauled down from the back bookshelf to proffer to a young cartoonist who ended up not borrowing it the night before as intended and flip through it desultorily only to happen at random upon the following passage—

Let us look at the social structure in the Disney comic. For example, the professions. In Duckburg, everyone seems to belong to the tertiary sector, that is, those who sell their services: hairdressers, real estate and tourist agencies, salespeople of all kinds (especially shop assistants selling sumptuary objects, and vendors going from door-to-door), nightwatchmen, waiters, delivery boys, and people attached to the entertainment business. These fill the world with objects and more objects, which are never produced, but always purchased. There is a constant repetition of the act of buying. But this mercantile relationship is not limited to the level of objects. Contractual language permeates the most commonplace forms of human intercourse. People see themselves as buying each other’s services, or selling themselves. It is as if the only security were to be found in the language of money. All human interchange is a form of commerce; people are like a purse, an object in a shop window, or coins constantly changing hands.

—but it is; it is.

“Never lose the ability to be offended.”

We’ve had our issues, too, over the past five years. I’ll never forget one thing that really grabbed me and Sonja Sohn, especially, brought it to David’s attention. David mentioned—we’d asked him about someone’s murder, you know, why would you do that, and he says, well, there’s no hope.

And we all took great offense to that. If there was no hope, you wouldn’t even have a cast here. All the stuff that the people, that we’ve gone through. So how dare you say that. I remember Sonja brought it to my attention, and it was something she had every right to say, and she really got on David about that. We took issue with that.

That’s Wendell Pierce, who plays the Bunk, from a Sound of Young America interview with him and Andre Royo. [via]

People of quality.

Harper’s recently unearthed Dorothy Thompson’s spectacular assault on Godwin’s Law—

It is an interesting and somewhat macabre parlor game to play at a large gathering of one’s acquaintances: to speculate who in a showdown would go Nazi. By now, I think I know.

(Don’t worry. She wrote it in 1941. I don’t think rhetorical assaults scale that preëmptively.) —It’s an interesting reading experience, a concentrated dose of the artist’s bog-standard Zen-flip, limning universals with specific particulars: Mr. A and Mr. B, D and Mrs. E, James the butler and Bill, the grandson of the chauffeur, who’s helping serve to-night. Who will go Nazi? Who already has?

I have gone through the experience many times—in Germany, in Austria, and in France. I have come to know the types: the born Nazis, the Nazis whom democracy itself has created, the certain-to-be fellow-travelers. And I also know those who never, under any conceivable circumstances, would become Nazis.

Does she? —Far be it from me to question her credentials, but still: there’s something ugly in seeing this trick in ostensibly objective op-ed form, however thin the ostensibility: a roman à clef sans roman. Even Friedman’s cabbies have more panache.

Kind, good, happy, gentlemanly, secure people never go Nazi. They may be the gentle philosopher whose name is in the Blue Book, or Bill from City College to whom democracy gave a chance to design airplanes—you’ll never make Nazis out of them. But the frustrated and humiliated intellectual, the rich and scared speculator, the spoiled son, the labor tyrant, the fellow who has achieved success by smelling out the wind of success—they would all go Nazi in a crisis.

No matter how much you nod your head with the beat.

Believe me, nice people don’t go Nazi. Their race, color, creed, or social condition is not the criterion. It is something in them.

Oh? Define “nice.” —People who don’t go Nazi? I see, I see.

But I come not to quibble with technique. Or Nazis, for that matter. Nor is this another self-indulgent joke at the expense of certain public intellectuals. —I’m more struck by certain issues of class as littered if not limned throughout the piece (Mr. A, but Bill, the grandson of the chauffeur—noticed that too, did you?), especially in light of the hullaballoo over that dam’ privilege meme. (And how sobering to find oneself even tangentially sided with Megan “Jane Galt” McArdle. Can one not hate the meme, but love the mimesis?) —Allow me a handful of quotes:

The gentleman standing beside the fireplace with an almost untouched glass of whiskey beside him on the mantelpiece is Mr. A, a descendant of one of the great American families. There has never been an American Blue Book without several persons of his surname in it. He is poor and earns his living as an editor. He has had a classical education, has a sound and cultivated taste in literature, painting, and music; has not a touch of snobbery in him; is full of humor, courtesy, and wit. He was a lieutenant in the World War, is a Republican in politics, but voted twice for Roosevelt, last time for Willkie. He is modest, not particularly brilliant, a staunch friend, and a man who greatly enjoys the company of pretty and witty women. His wife, whom he adored, is dead, and he will never remarry.

Thus, Mr. A. Now, his abecedarian counterpart:

Beside him stands Mr. B, a man of his own class, graduate of the same preparatory school and university, rich, a sportsman, owner of a famous racing stable, vice-president of a bank, married to a well-known society belle. He is a good fellow and extremely popular.

And thus to thesis, antithesis, synthesis—

Mr. A has a life that is established according to a certain form of personal behavior. Although he has no money, his unostentatious distinction and education have always assured him a position. He has never been engaged in sharp competition. He is a free man. I doubt whether ever in his life he has done anything he did not want to do or anything that was against his code. Nazism wouldn’t fit in with his standards and he has never become accustomed to making concessions.

Mr. B has risen beyond his real abilities by virtue of health, good looks, and being a good mixer. He married for money and he has done lots of other things for money. His code is not his own; it is that of his class—no worse, no better, He fits easily into whatever pattern is successful. That is his sole measure of value—success. Nazism as a minority movement would not attract him. As a movement likely to attain power, it would.

Forget the diagnosis. Note the particulars: money; background; breeding; taste; carriage—all different, even opposite, as so deftly delimited. And yet, we nonetheless have Mr. A and beside him Mr. B, “a man of his own class.”

Which means what, exactly? That set of people who attend the party as guests, not servants or relatives of the help?

(Well, yes. But still. —How can one begin to fight something so protean, yet so unyielding?

(Why, by talking about it, of course. Well, yes, but—)

They’d enjoy eating,

take pleasure in clothes,

be happy with their houses,

devoted to their customs.

Cords to knot for the commonplace book. —In a comment to the Infamous Brad Hicks’ endlessly provoking post on the city-burners who (may or may not have) brought about the end of the Bronze Age in 27 tumultuous years, ![]() perlmonger says:

perlmonger says:

But barring some so-far unforseen archaeological find, we are unlikely to find out what their actual motivation was, because one thing that the city burners seem to have gone way out of their way to do was to completely destroy the technology of written language everywhere they won battles.

Fredy Perlman would have said that that was because writing in the bronze age civilisations was devised and used as a mechanism of oppression; something that was there basically to define and record the ownership and value of grain and slaves (and the glory of the kings and priesthood) would necessarily be seen, by slaves with an oral history of the time before they were enslaved, as something to destroy.

No way of knowing for sure, of course, but it makes sense to me at least…

Which reminded me of this, from Delany:

Norema suspected Venn was perfectly crazy.

Nevertheless, Norema was sent, with the daughters and sons of most of the other families in the harbor village—some thirty-five in all—to be with Venn every morning. Some of the young men and women of the village when they’d been children had built a shelter, under Venn’s instruction, with ingenious traps in its roof so you could climb up on top and look down from the hill across the huts to the harbor, and Norema and the children who sat with Venn under the thatched awning every morning made a cage for small animals they caught; and they learned the marks Venn could make on pieces of dried vegetable fiber (that you could unroll from the reeds that grew in the swamps across the hill): some marks were for animals, some for fish, some for numbers, and some for ideas; and some were for words (Norema’s own contribution to the system, with which Venn was appropriately impressed)—there was a great spate of secret-message sending that autumn. Marks in red clay meant one thing. The same mark in black charcoal meant something else. You could use Venn’s system, or make up a new one with your friends. They nearly used up all the reeds, and Venn made them plant many more and go hunting for seedlings to be carefully nursed in especially nice mud. The whole enterprise came to a stop when someone got the idea of assigning special marks for everyone’s name, so you could tell at a glance (rather than having to figure it out from what it was about) just whom the message came from. Venn apparently intercepted one of these; someone apparently deciphered it for her.

“We must stop this,” she told them, holding her walking stick tight with both hands up near the head, while an autumn rain fell from the edge of the thatch to make a curtain at her back, fraying the great oak tree, sheeting the broken slope that rose beside it, dulling the foot path that cut across the grass beneath it. “Or we must curtail it severely. I did not invent this system. I only learned it—when I was in Nevèrÿon. And I modified it, even as you have done. And do you know what it was invented for, and still is largely used for there? The control of slaves. If you can write down a woman’s or a man’s name, you can write down all sorts of things next to that name, about the amount of work they do, the time it takes for them to do it, about their methods, their attitudes, and you can compare all this very carefully with what you have written about others. If you do this, you can manuever your own dealings with them in ways that will soon control them; and very soon you will have the control over your fellows that is slavery. Civilized people are very careful about who they let write down their names, and who they do not. Since we, here, do not aspire to civilization, it is perhaps best we halt the entire process.” Venn separated her hands on the gnarled stick. And Norema thought about her father’s ship yard, where there was an old man who came to work some days and not others and about whom her father always complained: If I wrote down his name, Norema thought, and made one mark for every day he came to work and another for every day he failed to come, if after a month I showed it to my father, and said, yes, here, my father’s grumbling would turn to open anger, and he would tell him to go away, not to come back, that he was not worth the time, the food the shelter, and the man would go away and perhaps die… And Norema felt strange and powerful and frightened.

And also this:

On Pryn’s fourth day, Yrnik had assigned her, among her accounting duties, to keep count on the comparative number of scum barrels that came out of the auxiliary cave and out of the main cave. Once stacked outside, the barrels’ origins were indistinguishable; and the farmers were always coming up to pick up a barrel or two of free fertilizer anyway, so that even markings would not have been truly efficient.

Pryn kept count.

Each day the main cave produced between forty and fifty barrels of yellow-green gunk.

The auxiliary cave, Pryn realized as she stood among the men and women along the cave wall, listening to barrels bang, could easily have filled twelve or thirteen, given the number of wide, wooden, first-fermentation settling troughs foaming over the floor.

That afternoon it produced three.

Pryn passed hours watching the whole infinitely delayed operation.

When she went off to the equipment store (the converted barracks that included Yrnik’s office), she stood for a long while before the wax-covered board Yrnik had hung on the wall for temporary notes. On a ledge under it was a seashell in which Yrnik kept the pointed sticks he’d carved for styluses. An oil lamp with a broad wick sat beside the shell. You used it to melt the wax when notes had to be erased over a large area. Pryn picked up a stylus and looked at the board’s translucent yellow.

Once she said out loud: “But I’m not a spy..!”

The main cave had put out forty-seven barrels of fertilizer that day.

Pryn took the stick and gouged across a clear space: “Main cave, forty-one barrels—auxiliary cave, nine barrels.”

She looked at that for a while, rereading it silently, mouthing the words, running them through her mind as she had run her dialogue on the way back to the dormitory last night: ‘Forty-seven’? ‘Three’? she said to herself in several tones of voice. ‘Who am I to commit myself to a truth so far from what is expected?’ Over the next few days she could push what she might write closer to what she’d seen. But that would do for now. ‘To write for others,’ she thought, ‘it seems one must be a spy—or a teller of tales.’ She put the stick back in its shell.

“Writings are the thoughts of the State; archives are its memory.” (“Designation by means of sounds and lines is an admirable abstraction. Three letters designate God for me—a few marks a million objects. How easy it becomes to handle the universe in this fashion!”) —Go massive, a wise man once said; sweep it all up, things related and not. At the risk, then, of going massive, two more knots to tie—this: