“You can tell him by the liberties he takes with common sense, by his flashes of inspiration, and by the fact that sooner or later he brings up the Templars.”

So, right: the default response to a post from John C. Wright, then, turns out to be exactly the same as the default punchline to a New Yorker cartoon. (—And I have to keep reminding myself: this is from the intellectual end of the rump.)

The hairs of my chin bristle as I repeat it, silently—

Autumn Fugue

A book was sometimes held in your hand

when the Committee on Understanding met

as you waited for them to call you in

& the man who mowed the graveyard

waved with a circular wave

in the manner of cousins under the elm

where it seemed sweet spices

had been cast down near accordion streets

so once the small democracies

had begun, time could make an exception

for owls with the faces of seeds

that looked just like themselves only open;

it is late & sweet with a late

democratic sweetness when seeds

had been cast down in the manner of

spices, where once the small committees

had begun, time played accordion

with its foot in the door, & you felt

at ease in a circular way

so even had the parties called your name

you would not have been wrong;

the elms had made an exception

& a book was sometimes found in your hand

that looked just like itself, only open—

For DY

Cochliomyia hominivorax delendum est.

How’s that for eliminationist rhetoric?

I feel vaguely guilty, making such a deal of accepting John C. Wright into my life. After all, what’s he done since then? A turgid apologia (i, ii, iii, iv, v, vi) that in no way indicated he’d thought at all as promised on what the Elders of Sodom had wrote, and an all-but-unreadable screed against empiricism (I think): Neo cannot say why he chooses to fight, and thus homosex is wrong, quod erat dammit. Overall a disappointing performance I must say.

—And then John H. Richardson has to cast a chilly pall over the whole enterprise anyway by going and talking to Mike Austin, an eighth-grade teacher in Oklahoma who until recently was saving the world one essay at a time over at the Return of Scipio.

Yeah, that Return of Scipio. Took me a minute too.

And Richardson has a lovely conversation or two with Austin, who seems a much nicer person than the Scipio Resurgent, much I’m sure as John C. Wright is much nicer than ![]() johncwright; he seems a hale enough fellow, I suppose, who could essay a hearty laugh—but that’s just how it works. Most of us are better than our manifestos.

johncwright; he seems a hale enough fellow, I suppose, who could essay a hearty laugh—but that’s just how it works. Most of us are better than our manifestos.

But still and all:

As we drive back to my hotel through the clean wide streets of Oklahoma City, I take a chance on some gentle teasing: “Everything’s so well-groomed, you got no garbage, no graffiti—I do not see the collapse of American civilization here.”

His answer comes out cold as a can from a Coke machine: “If you were to look at the streets of Nazi Germany in 1936, they would appear a lot like this. Probably cleaner.”

I’ve heard this exact argument before, from the Glenn Beck follower types, but I can’t believe they really mean to compare their fellow Americans to the most cold-blooded killers in human history. It must be rhetoric. They can’t be that alienated from the society that has given them, beyond any civilization in history, lives of such extraordinary privilege and comfort. My voice rises with my exasperation. “You could say that about any town anywhere!”

His answer comes back steady and patient, like he’s explaining history to one of his eighth graders. “The government in Washington, DC has encroached so much on states’ rights, it seems like we don’t have a federal system any more, rather an imperial one. And when the states lose their rights guaranteed in the Constitution, then what you have is tyranny.”

Obama is a fascist, he continues. Setting the limits of investment-bank incomes and claiming the right to seize General Motors are just two examples. Where in the Constitution does it grant him those powers? Are we a nation of laws, or is this a lawless regime that sends out its goons like Mussolini?

(And there it is, the voice of the blog: What has always stood against lawless men? Force. That is the only idiom understood by such men. To answer lawless men with force is to speak their language.)

[…]

“There are things worse than violence, John,” Austin tells me. “Slavery is worse than violence. The most peaceful place in the world is the cemetery.”

It is really a quite serious matter that the right-wingers have gone around the bend and apparently aren’t coming back…

There’s a new outfit in town—

—whose name’s suggested perhaps by all the glittering potentates who came to do homage to the aforementioned Elders of Sodom on receipt of their open letter to Wright. The basic mission statement for members reads as follows:

As a member of the Outer Alliance, I advocate for queer speculative fiction and those who create, publish and support it, whatever their sexual orientation and gender identity. I make sure this is reflected in my actions and my work.

This first of September, the Kalends of Sextilis, they’re asking for a show of hands. They suggest a link to fiction which is in any way on mission, and while there’s this or that I could point to, there’s also this or that game I don’t want to give away, and so instead I’ll highlight an old series of posts:

It’s how I started swatting at screwflies, anyway.

John C. Wright will of course forever be known for or at least in light of his hatred of homosex, but for all that he can’t bring himself to wish for the destruction of its practitioners, adherents, and supporters; at worst, we all get to sit in closets again, as Morality ever-so-passively just somehow returns. —Mike Austin, the (former) Scipio Resurgent, is at once more cosmopolitan and strict (then, Scipio was famously Græcophilic), but even he can’t bring himself to take the action he seems to think is vital; can’t help but laugh with the mainstream media man who’s come to talk to him; can only lash out at abstract ideas that have never set foot in Oklahoma or anywhere else. —They may have gone around the bend, but there’s enough shame yet to prevent them from actually advocating the clear, precise, destructive, eliminationist praxis needed to bring about the world they think they want.

And where there’s shame, there’s hope?

Room enough, anyway, for words: and enough of them, from stories told, from lives lived, from experiences actually had, will always outweigh an argument merely propounded.

We’ve always been better than our manifestos.

John C. Wright is recoiling in craven fear and trembling, and I don’t feel so good myself.

Actually, I don’t know that he’s necessarily recoiling in craven fear and trembling. But: he has taken down his storied post, “More Diversity and More Perversity in the Future!” in which he excoriated the SyFy [sic] channel for “recoil[ing] in fear and trembling when lectured by homosex activists,” after said post received 800+ lecturing, hectoring comments; and besides, I can never pass up an obscure joke.

I’ve been going by his LiveJournal every night now, ever since I caught a link to that rant (via the Mump), and I figured out this was that guy who wrote those books I’ve never quite gotten around to picking up—and now I can’t tell whether I’m glad I dodged a bullet, or whether I wish I hadn’t.

Tonight, after nuking the aforementioned storied post, he (in the course of defending his apology) posted the following:

First let us clarify who the enemy is. It is not the homosexuals. The enemy is the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) that are devoted to a Leftwing antinomian agenda, and willing and eager to use pressure tactics to enforce the doctrinal conformity so near and dear to the heart of the Left.

Which is me giving you the full context of the paragraph, and not the experience of reading it; the experience of reading it was rather more like—

The enemy is the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) that bleep! does not compute

When I found my jaw and resettled it on my face I found myself nodding along—well, yes, in a world in which the homosexual lobby is for the most part comprised of happily married heterosexuals, well, sure, perhaps there might very well be something sinister about their devotion to an antinomian agenda. —That our world, the world in which both I and John C. Wright unarguably exist, does not in any way resemble this world does not in any way invalidate the logic; merely the premise.

Sorry. Jaw’s still a little loose. —There.

I tried to post a comment. I was going to quote the bit about the homosexual lobby (who for the most part are happily married heterosexuals) and I was going to ask whether I might ask how he came by this particular fact. But he’s locked down comments to his LiveJournal; only those he’s added as friends are allowed to comment at all. The rest of us are banned.

Can’t say I blame him. The shitstorm was mighty. Battening the hatches is only rational.

MacAllister and I have not exactly been arguing or even discussing but more like honing points off each other. I’m going to quote hers first because it’s my blog and I get the last word, and I’ll grab hers from this tor.com thread:

I think we cannot conflate the art and the artist.

Actually, what I think is more vehement than the above statement.

In 1953, Isaac Asimov called SF “that branch of literature which is concerned with the impact of scientific advance upon human beings” and I find that description compelling precisely because so much of the impact of science upon human beings has precisely to do with issues that, once upon a time, were dictated to us by shamans, holy men, or chicken entrails.

I think it’s damaging to conflate the art with the artist. The writer is not the book. When we’re talking about the literature of ideas, especially, I think it’s damaging to us as thinkers, readers, and writers to artificially and arbitrarily shield ourselves from ideas we disagree with, find unpleasant, or even repugnant.

And there is nothing in that I do not agree with, but—and I’m going to grab mine from a whiles back when the Islets of Bloggerhans were talking about Orson Scott Card again because, you know, not inappropriate:

Science fiction is largely a fiction of setting: the bulk of the iceberg that’s unseen, underwater, is the act of world-building, and in that act, politics is paramount. (One is building a polis, after all.) —Therefore, it’s all-too-appropriate to keep in mind an author’s politics when considering their science fiction: an author who, say, considers homosexuality to be an aberration, is un- (or perhaps less) likely to build a world that would appeal to a reader who does not. There’s an assumption clash: one of his fundamental, foundational bedrocks is abhorrent to me, and vice-versa.

One can respond: well, yes, but there’s nothing about aberrant homosexuality in Ender’s Game, so how can it clash? Heck, there’s nothing in that book about homosexuality at all! And I will resist the urge to say oh, you think so? and I will even resist the urge to say precisely! —Instead, I’ll allow as how there’s frequently large gaps in the jerry-rigged polis left as exercises for the reader: one can hardly describe every kitchen sink, after all; one must make assumptions, and count on the reader doing likewise (which among other reasons is why fan fiction [and slash fiction] is so popular in science fiction). But that’s precisely why when those assumptions suddenly clash, it’s unsettling, even violently dissonant.

Which is why it’s not an argument and hardly a discussion. I’m talking about why I’m no longer terribly interested in reading Card’s work, nor Wright’s; she’s talking about why such work must remain available to be read. —A book doesn’t always have to be an axe for the frozen sea within, for God’s sake, but one should never lose the ability or God forbid the inclination to read for the hacking. But when the only challenge a book’s likely to pose is the challenge not to throw it across the room—

Why’d this come up in the first place? —Most of the 800+ comments to that storied post were along the lines of “I’ll never read your books again, thanks for warning me off, you’ll never get dime one of my money.” (“Every time you bloviate offensively on the internet, a reader swears off your work for life,” says Catherynne Valente, in one of the many open letters to Wright that have sprung up of late.)

Now, there’s a difference between “I do not wish to read you, or support you with my money,” and “You should never be published ever again!” though I can appreciate how it might be a difficult distinction to make on the receiving end. Especially when it’s more overtly couched as a boycott: “I’m never buying a Tor book again so long as they keep publishing writers like you.” (I’m sure John Mackey can sympathize.) But there’s also a difference between “You should never be published again!” and “I’ve fucking had it with living in world where you and yours make the rules!” —And I think what it is is my Emma Goldman baseline’s not wanting to be part of a revolution that depends on shutting people up.

Even if one of the ways I try to keep my little corner of the world safe from them and theirs is to, you know, not bother to read works by this author or that.

Barry and I were emailing about Wright and Card and suchlike. “Ah!” I said at one point. “Sitting in judgment of other people with my morning coffee on a chilly day off from work with a baby in my lap. —Have I mentioned how glad I am she’ll grow up in a world where these moral monsters are marginalized? Have I mentioned how terrified I am I’m wrong?”

That initial, storied post is an ugly thing, a ham-handed attempt at excoriating the SyFy [sic] channel from an infantilely Manichean lex naturalis, full of the sneering braggadocio of a playground bully preening for his sycophants (says me, with a sneer). —His basic argument (expounded in a later comment to that post) was a syllogism in Camestres:

Odd as it sounds, I was fully loyal to the sexual revolution as an idea. Then someone tried to convince me that two lesbians licking each other in the crotch was the same in all ways, just as sacred, just as romantic, just as normal, just as beautiful as Romeo and Juliet, Tristan and Iseult, Micky and Minnie, Adam and Eve, Jove and Juno, Father Sky and Mother Earth, me and my wife.

(Or Ruth and Naomi? says me, preening.) —And yes, the premises fall apart in your hand when you gingerly try to pick them up, but yes, it’s a just-so story, and thus irremediable to them what believes. What’s striking is the ugliness of the language, the revulsion, the almost-desperate hodgepodge of totemic icons thrown up in defense, all in an argument that insists on the rigor of its logic, on the intractable ad hominemity of the other side. It seems to have struck Wright, too:

I think my posts were accurate but were not measured.

Let me give you a hypothetical:

Imagine standing in the waiting room of a hospital, and overhearing a doctor joking with a nurse about some patient about to die, and the doc uses gross slang to describe the patient’s bowels dissolving and so on—and you realize that patient is your loved one.

Now, the doctor said nothing untrue, and he was engaged in what actually he thought a private conversation (even if it was in a public spot). But you would be shocked, and he should be careful of your feelings.

And—well, yes, the analogy’s strained and rather terribly objectionable, but the basic sentiment, the apology itself, that’s sound enough, surely? Commendable, even, in an internet where no one ever walks anything back ever? (Though it’s with a poor and a threadbare, sketchy grace: “I had damn well better offer these people, enemies or not, the olive branch, and quickly. They will not accept it, if I am any judge of character: indeed, they will take it as a sign of weakness and redouble their efforts. But that is not my concern and not the orders I was given.”)

Except—the “you” above is a very particular, rather singular you, with a very particular and singular loved one who’s about to (figuratively) die:

There was one commenter whose feelings I actually hurt. His mother is a homosexual, and he was rightfully offended at the language I used to describe homosexuality. Him I apologized to privately, but I would also like to do it publicly. It is hard to tell, just from reading words, when people are being sincere, and when they are not, but I thought this one guy was sincere, and that most of the rest of you were engaged in rhetoric.

To him, wherever he is, I am sorry. I regret my words, and I regret my thoughtlessness. Please forgive me.

—And the queerly thrilling horror that’s been creeping over me the past few days comes sharply into focus, with all this talk of a monolithic Left and their antinomian agendas and a homosexual lobby filled with heterosexual couples and a straight Sappho and the evil space monkeys: he literally does not realize that every single person who snapped at him in the 800+ comments left on that storied post, every single one, was reacting out of anger that had come through grief, was just as rightfully offended by the language he’d used, was no matter how rude in response just as deserving of apologies both public and private, that each of them was or loved or knew someone whose life had been bent or broken or wrecked or deflected by the appallingly arbitrary rules he was defending, his dreadfully unnatural lex naturalis—

Yeah, but I wasn’t going to do, well, that.

This was about—what, exactly? Grace, yes, and the koan; trying to get past the two-minute hate—I did say it was anger that came from the grief, and did allow as how the responses were rude (and got my own licks in: “Shorter Wright: My sexual peccadilloes are moral imperatives; your sexual peccadilloes are suspect; their sexual peccadilloes are disgusting”—hardly one of my finer moments)—but trying to make a point of how maybe one should listen to an objectionable author just as one might listen to their works, when really you’re more than ready to sit in judgment on a chilly August night over a splash of bourbon, is just as chary as offering up an olive branch you’re ready to snatch back at the first rebuff. —And there’s more than a little disaster tourism in all this, too, which I realize mucks up the clarity of that up there, but none of our motives are ever pure.

And maybe if I did get a chance to ask him directly how he came by the striking notion that the homosexual lobby are for the most part happily married heterosexuals, he’d just tell me that by “homosexual lobby” he meant, of course, the monolithic Left, and as homosexuals comprise a minority of the Left much as they do the population at large well QED, but maybe he wouldn’t; I don’t know. There’s a herky-jerky searching quality in all the self-serving bluster that, well. Doesn’t so much fill me with hope. But it’s certainly captured my attention the past few days.

Or maybe it’s just I have a weakness for pompous brio. —Whichever; anyway, tonight I added John C. Wright as a friend over to the LiveJournal.

(Oh, I added Catherynne Valente, too. After all, her baseline work for the bare minimum hit of the stuff she’s jonesing for, for which she’d forgive an artist just about any asshattery, is Mark Helprin’s Winter’s Tale—and what are the odds? So’s mine!)

μῶμος.

At the age of 15, Humperson ran away from home to become a lighthouse keeper on the rugged, storm-lashed Atlantic coast. During this time he worked on a new signaling system intended to warn sailors of the various complex dangers—extending far beyond mere storms and rocks—presented by the sea. Unfortunately, because of widespread unfamiliarity with the system amongst sailors, wrecks were caused and a great many lives lost. Humperson fled to Jerusalem, where he studied anthropology and sociology in Hebrew under Martin Buber.

It was here—swatting flies in the fierce Palestine sun—that he began to develop the ideas for which he’s best remembered. Later, as a tenured professor at the University of San Marino, Humperson developed these preliminary insights into the five Laws of Meta as we know them today—

Momus extols an uncelebrated thinker.

Crap.

Saw this taped to the back window of a Suzuki on the way into work, not so much a bumper sticker as a placard—

A government big enough to supply you with everything you need, is a government big enough to take away everything you have…

—Thomas Jefferson

And I hope your nose wrinkled as immediately at that as mine did: I hope the horrid clanging dissonance between the words spoken and the speaker putated, in language, in political and historical consciousness, in punctuation, struck you as hard and as fast as it did me. “Bullshit,” I snarled, with perhaps more vituperation than was absolutely necessary, but commuting makes me cranky, and anyway he was driving like a dick.

But, I thought to myself mere moments after the outburst, is it really? —Bullshit implies some awareness on the bullshitter’s part of the truthy nature of one’s utterances. If one were in the course of a heated discussion on the un-American nature of single-payer health care to suddenly bust out with “Oh, yeah, well I think it was Jefferson once said that a government big enough to yadda yadda” then I think we could all agree that one was bullshitting us with a cliché draped in a disastrously silly argument from authority and move on from there. But to print it out and tape it to the back window of your car for all to see one’s apparent ignorance of the language, the historical and poltical consciousness, the punctuation of the very Founding Fathers to whose imprimatur one so desperately clings? To so apparently believe the thing so clearly wrong? —We need a different word, I think.

Horseshit?

But the relationship between the two is close, perhaps too close: most horseshit begins as bullshit, for instance, much as the example above—the words are the same; it’s the purveyors’ attitudes toward them that make the only difference. And what of those who deploy bullshit to defend a core notion of horseshit: does the reliance on what one ostensibly knows to be truthy call into question the degree of one’s actual ignorance of the truthiness of that which one’s defending? And think of the nightmarish, irresolvable arguments over Liberal Fascism: bullshit or horseshit?

Also, the bull and the horse don’t work so well in the metaphoric relationship. —Maybe it’s all bullshit, and it’s more that there’s those who shovel it, and those who don’t seem to notice they’re walking around covered in it?

(Gerald Ford, August 12, 1974: “A government big enough to give you everything you want is a government big enough to take from you everything you have.” Jefferson said, “The natural progress of things is for liberty to yeild [sic], and government to gain ground.” —Lost lashings of nuance aside, theories as to why Ford got transmogrified into Jefferson as the authority from which to argue tingle deliciously, don’t they?)

On a clear day you can see the ambiguous heterotopia.

“You’re supposed to have slightly less than one-fifth of your population in families producing children,” the man with the beard and rings said, “and at the same time, slightly over a fifth of your population is frozen on welfare…” Then he nodded and made a knowing sound with m’s that seemed so absurd Bron wondered, looking at the colored stones at his ears and knuckles, if he was mentally retarded.

“Well, first,” Sam said from down the table, “there’s very little overlap between those fifths—less than a percent. Second, because credit on basic food, basic shelter, and limited transport is automatic—if you don’t have labor credit, your tokens automatically and immediately put it on the state bill—we don’t support the huge, social service organizations of investigators, interviewers, office organizers, and administrators that are the main expense of your various welfare services here.” (Bron noted even Sam’s inexhaustible affability had developed a bright edge.) “Our very efficient system costs one-tenth per person to support as your cheapest, national, inefficient and totally inadequate system here. Our only costs for housing and feeding a person on welfare is the cost of the food and rent itself, which is kept track of against the state’s credit by the same computer system that keeps track of everyone else’s purchases against his or her own labor credit. In the Satellites, it actually costs minimally less to feed and ouse a person on welfare than it does to feed and house someone living at the same credit standard who’s working, because the bookkeeping is minimally less complicated. Here, with all the hidden charges, it costs from three to ten times more. Also, we have a far higher rotation of people on welfare than Luna has, or either of the sovereign worlds. Our welfare isn’t a social class who are born on it, live on it, and die on it, reproducing half the next welfare generation along the way. Practically everyone spends some time on it. And hardly anyone more than a few years. Our people on welfare live in the same co-ops as everyone else, not separate, economic ghettos. Practically nobody’s going to have children while they’re on it. The whole thing has such a different social value, weaves into the fabric of our society in such a different way, is essentially such a different process, you can’t really call it the same thing as you have here.”

“Oh, I can.” The man fingered a gemmed ear. “Once I spent a month on Galileo; and I was on it!” But he laughed, which seemed like an efficient enough way to halt a subject made unpleasant by the demands of that insistent, earthie ignorance.

—Samuel R. Delany, Trouble on Triton

Triton broke my brain more than any other book I ever read as a kid: I saw things differently after I read it—politics, sexuality, protagonists, sf. I read differently after I read it. And part of it was the thorny, prickly, problematic, nonexistent government of Triton and all the other Satellites, where you’re free to live under whatever system you want to vote for, or squat in the unlicensed free zones of whatever city you like—but behind it all that immutable, implacable, eminently sensible hand that invisibly takes what each might provide and in turn provides what each might need, but that also enables its agents to speak of “a” state and “a” system and to wage war on its behalf let’s not forget.

But it’s this idea of welfare, this road-not-taken over on the other side of the gulch from years of Reagan-Bush-Clinton, this road we might never have been able to take, but is nonetheless so dam’ sensible, where everyone’s given a hand up when they’re setting out regardless of etc. (and where everyone’s a stakeholder, and thus the system’s as untouchable as Social Security)—it’s this that came to mind when I read about a recent appearance on Glenn Beck’s medicine show by the Incredible paterfamilias himself, Craig T. Nelson, who in the course of a rant on how he’s sick of paying taxes for things that do not benefit him by God, said the following—

I’ve been on food stamps and welfare. Did anybody help me out? No!

It’s becoming clear that the question that will define the early 21st century is this: can the white man create a sense of entitled privilege so large even he can see it?

All signs point to no.

Cross-pollination.

I wanted to take a moment, just a moment, to share with you a couple of morsels from ![]() teaotter’s distillation of

teaotter’s distillation of ![]() ithurtsmybrain’s list of Pairings that Ate Fandom:

ithurtsmybrain’s list of Pairings that Ate Fandom:

From her “I’ll be in my bunk” list:

84. Nikola Tesla (The Prestige) / Sarah Connor (Terminator/SCC)

And you know? That works very, very well. It’s an intriguingly doomed disaster of a relationship in waiting, it is. But this next one, this:

From her “That would be (deliciously) wrong” list:

98. James Bond (James Bond films) / Bella Swan (Twilight)

I just. I mean. Words fail, you know? I mean.

Re: the new Whedon.

C+, for now, with some caveats. It’s not the gender stuff I’m on about; if you’re squicked, and you probably are, it’s in the mission statement, and remember he’s made yet another devil’s pact with the Maxim of network television, and if you can’t ultimately bring down the master’s house with the master’s tools you can at least wreak some interesting havoc before they come take them away. —I’m more keen to see what might be done with class: “normal” people on TV have always been (with some notable exceptions) what would be comfortably wealthy in the real world; the folks here have all the same material trappings of TV-normal, but they’re actually acting like the rich. So I want to see some mammalian certainties.

Other than that: everybody’s saying Topher’s the Xander of this one. Well, if by Xander you mean the young guy with the cynical wisecracks, I suppose, but that was never really what Xander was. Xander was the gut, as the Spouse likes to put it; the moral ground, the I-guy somewhat taken aback by all the paranormal goings-on, who calls bullshit despite the beam in his own eye, and is right more often than not; the mammal, as it were, which means Boyd Langton is the show’s Xander, thankyouverymuch.

No, Topher—the mad scientist, who lovingly details the backstories of the characters he creates every week for his Actives to play—Topher is the show’s Whedon.

But keeping that in mind will excuse only so much turgid dialogue. Up your game, people!

Tlön, Uqbar, Custodis Tertius.

I finished the book, I gave it to my agent, and I said, “I want this on Henry Selick’s desk.” Henry sent me a script. My notes to Henry’s first script were, “It’s too faithful, Henry.” My notes to Henry’s second script were, “Yeah, that’s pretty good.”

—Neil Gaiman (on Coraline)

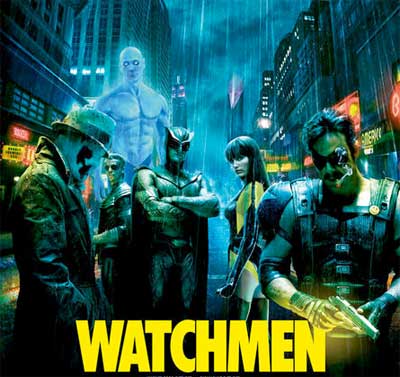

Snyder says his adaptation of Warner Bros. Watchmen, slated for release next March, is more true to the source material than was the Oscar-winning No Country for Old Men.

—300 director brings Watchmen to Comic-Con

Watchmen’s Axis of Evil has a Dangerous “Package”

To stand inside the Owl Ship... and to smell the Comedian’s cigar, to have the Comedian slap me on the back and proudly show me his guns... I was completely thrilled.

Centuries and centuries of idealism have not failed to influence reality. In the very oldest regions of Tlön, it is not an uncommon occurrence for lost objects to be duplicated. Two people are looking for a pencil; the first one finds it and says nothing; the second finds a second pencil, no less real, but more in keep with his expectation. These secondary objects are called hrönir and, even though awkward in form, are a little larger than the originals. Until recently, the hrönir were the accidental children of absent-mindedness and forgetfulness. It seems improbable that the methodical production of them has been going on for almost a hundred years, but so it is stated in the eleventh volume. The first attempts were fruitless. Nevertheless, the modus operandi is worthy of note. The director of one of the state prisons announced to the convicts that in an ancient river bed certain tombs were to be found, and promised freedom to any prisoner who made an important discovery. In the months preceding the excavation, printed photographs of what was to be found were shown the prisoners. The first attempt proved that hope and zeal could be inhibiting; a week of work with shovel and pick succeeded in unearthing no hrön other than a rusty wheel, postdating the experiment. This was kept a secret, and the experiment was later repeated in four colleges. In three of them the failure was almost complete; in the fourth (the director of which died by chance during the initial excavation), the students dug up—or produced—a gold mask, an archaic sword, two or three earthenware urns, and the moldered mutilated torso of a king with an inscription on his breast which has so far not been deciphered. Thus was discovered the unfitness of witnesses who were aware of the experimental nature of the search... Mass investigations produced objects which contradicted one another; now, individual projects, as far as possible spontaneous, are preferred. The methodical development of hrönir, states the eleventh volume, has been of enormous service to archæologists. It has allowed them to question and even to modify the past, which nowadays is no less malleable or obedient than the future. One curious fact: the hrönir of the second and third degree—that is, the hrönir derived from another hrön, and the hrönir derived from a hrön of a hrön—exaggerate the flaws of the original; those of the fifth degree are almost uniform; those of the ninth can be confused with those of the second; and those of the eleventh degree have a purity of form which the originals do not possess. The process is a recurrent one; a hrön of the twelfth degree begins to deteriorate in quality. Stranger and more perfect than any hrön is sometimes the ur, which is a thing produced by suggestion, an object brought into being by hope. The great gold mask I mentioned previously is a distinguished example.

—Jorge Luis Borges, “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”

In 1985, DC Comics acquired a line of characters from Charlton Comics. During that period, writer Alan Moore contemplated writing a story featuring an unused line of superheroes that he could revamp, as he had done in his Miracleman series in the early 1980s. Moore reasoned that MLJ Comics’ Mighty Crusaders might be available for such a project, so he devised a murder mystery plot which would begin with the discovery of the body of The Shield in a harbor. The writer felt it did not matter which set of characters he ultimately used, as long as readers recognized them “so it would have the shock and surprise value when you saw what the reality of these characters was.” Moore used this premise and crafted a proposal featuring the Charlton characters titled Who Killed the Peacemaker, and submitted the unsolicited proposal to DC managing editor Dick Giordano. Giordano was receptive to the proposal, but the editor opposed the idea of using the Charlton characters for the story. Moore said, “DC realized their expensive characters would end up either dead or dysfunctional.” Instead, Giordano convinced Moore to rework his pitch to feature original characters. Moore had initially believed that original characters would not provide emotional resonance for the readers, but later changed his mind. He said, “Eventually, I realized that if I wrote the substitute characters well enough, so that they seemed familiar in certain ways, certain aspects of them brought back a kind of generic super-hero resonance or familiarity to the reader, then it might work.”

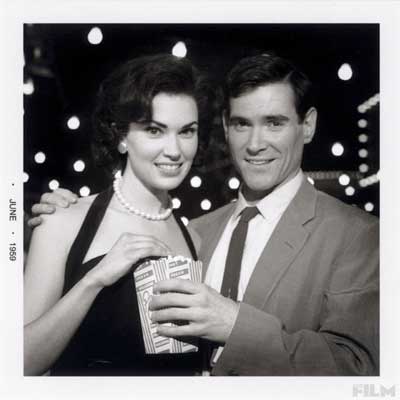

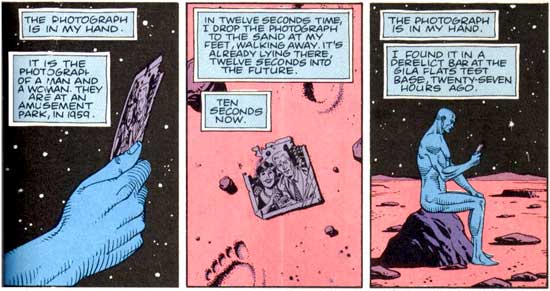

Jon Osterman and Janey Slater pose for a significant photo.

In the second panel, the dialogue is word-specific; that is, “the words provide all you need to know, while the picture illustrates aspects of the scenes being described” (130). Word-specific captions are often used to compress time—slap “thirteen years later” on any picture and there you are, thirteen years later—but here Moore uses them to move us back and forth through time. Without the captions, the transition from the first to second to third panel would seem occur via action-to-action, because the panels follow a single subject in a series of actions: Dr. Manhattan holds the photo, drops it, picks it back and sits down. (Keep in mind for later: were that the case, we would have inferred actions not actually pictured.) The word-specific captions inform us that the transition is actually scene-to-scene.

McCloud defines scene-to-scene as “transitions across significant distances of time and/or space” (15). Moore deliberately confounds that expectation in order to prepare the reader for twenty-six pages focused on a character for whom:

- the year 1959 (mentioned in the first panel) is no more significant a distance in time than twelve seconds from now (depicted in the second panel)

- Mars (depicted in the first three panels) is no more significant a distance in space than the Gila Flats (mentioned in the third panel and depicted in the fourth)

—Scott Eric Kaufman, “How to teach comics responsibly in a composition class”

There are no nouns in the hypothetical Ursprache of Tlön, which is the source of the living language and the dialects; there are impersonal verbs qualified by monosyllabic suffixes or prefixes which have the force of adverbs. For example, there is no word corresponding to the noun moon, but there is a verb to moon or to moondle. The moon rose over the sea would be written hlör u fang axaxaxas mlö, or, to put it in order: upward beyond the constant flow there was moondling. (Xul Solar translates it succinctly: upward, behind the onstreaming it mooned.)

The previous passage refers to the languages of the southern hemisphere. In those of the northern hemisphere (the eleventh volume has little information on its Ursprache), the basic unit is not the verb, but the monosyllabic adjective. Nouns are formed by an accumulation of adjectives. One does not say moon; one says airy-clear over dark-round or orange-faint-of-sky or some other accumulation. In the chosen example, the mass of adjectives corresponds to a real object. The happening is completely fortuitous. In the literature of this hemisphere (as in the lesser world of Meinong), ideal objects abound, invoked and dissolved momentarily, according to poetic necessity.

—Borges, op. cit.

The most obvious sense in which Watchmen is tethered to comics is the fact that it’s specifically about comics’ form and content and readers’ preconceptions of what happens in a comic book story. Beneath that surface, though, it relies on being a comic book for its crucial sense of time and chronology. The amount of time the reader has to spend working through the story isn’t the same as the amount of time the events in the story encompass—it’s longer—and the direction in which the reader experiences the story isn’t linear but keeps skipping backwards to revisit the past, as the narrative does.

Perhaps somebody at some point has read Watchmen straight through, but one of the joys of reading it is flipping back to see how images and scenes have been set up.

—Douglas Wolk, Reading Comics

Worry not, fans of brutal superheroes: The rape that’s central to Watchmen’s complex character dynamics will be featured in the movie without any censorship. Maybe just the opposite, in fact.

Talking to MTV, Jeffrey Dean Morgan—who plays the Comedian in Zack Snyder’s movie adaptation of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ classic comic—said that the scene where his character is discovered raping Carla Gugino’s Silk Spectre wasn’t an easy one to shoot:

It was a three-day process shooting that particular scene, and it was hard... It was three of the hardest days of filming I have ever had to do. It was really very violent.

Violent, you may be thinking? Wasn’t it kind of... understated in the original comic? Well, yes, but certain liberties have to be taken in adapting things into movies, Morgan explained:

When you’re looking at the comic book you only get a couple panels so there is a lot of stuff there that needs to be filled in, so we fill in the blanks there between three and four panels, and it turns out to be one hell of a violent scene. And it’s all intact, [Hooded Justice] comes in and interrupts the attempted rape—it’s all there. We stayed very loyal to it, and I haven’t actually seen the scene yet, but I did see a piece of playback when we were filming it and it’s a lot... It’s rated R for a reason.

—“Watchmen’s Rape Scene is Intact... And Violent”

Watchmen fans were thrown into a tailspin over the weekend when fans reporting in from the film’s first test screening in Portland carried out with them shocking news. In the version they saw, Zack Snyder had changed the ending of the comic. If you don’t want that ending spoiled for you, then read no further because this entire page will be devoted to nothing but an in depth discussion of what it might mean for the future of Watchmen, if the ending really does play out as reported.

—“Great Debate: Does Watchmen Need A Giant Squid?”

IGN

The big question: What have you got against the squid?!

Zach Snyder

I had a bad calamari experience as a child! Look I’ve got nothing against the squid. When I sat down with the studio and talked about the film, we had to make a decision about what stuff we included and what stuff we wouldn’t. For me Watchmen is all about the characters, whereas if we included the squid, I would have to illustrate it in the story and cut out some of the character. So I wanted more character and less story.

So we came up with something else—no one knows yet what we’ve done but we hope it’s similar in philosophy to the ending of the graphic novel. I mean the end is all about taking a superhero all the way—you know it’s the bad guy who is the one who wants world peace. It’s a moral dilemma for all the characters involved.

Dave Gibbons

The tone of the graphic novel—the message, the moral ambiguity—has still been left intact. Also it’s not a squid; it’s a fifth dimensional phalymapod!

—“Director Discusses Watchmen Squid”

About 1944, a reporter from the Nashville, Tennessee, American uncovered, in a Memphis library, the forty volumes of the First Encyclopedia of Tlön. Even now it is uncertain whether this discovery was accidental, or whether the directors of the still nebulous Orbis Tertius condoned it. The second alternative is more likely. Some of the more improbable features of the eleventh volume (for example, the multiplying of the hrönir) had been either removed or modified in the Memphis copy. It is reasonable to suppose that these erasures where in keeping with the plan of projecting a world which would not be too incompatible with the real world. The dissemination of objects from Tlön throughout various countries would complement that plan...

—Borges, op. cit.

IGN

Were you disappointed that Alan Moore didn’t want to be involved?

Snyder

Alan asked if his name could be removed from the film and not to be mentioned at all in relation to it—

Sunday morning bang and whimper.

Maybe it’s just me? Probably it’s just me. But there’s something oddly—comforting is the wrong word—about the interference pattern you get when you set this story—

From the beginning we were prepared, we knew just what to do, for hadn’t we seen it all a hundred times?—the good people of the town going about their business, the suddenly interrupted TV programs, the faces in the crowd looking up, the little girl pointing in the air, the mouths opening, the dog yapping, the traffic stopped, the shopping bag falling to the sidewalk, and there, in the sky, coming closer… And so, when it finally happened, because it was bound to happen, we all knew it was only a matter of time, we felt, in the midst of our curiosity and terror, a certain calm, the calm of familiarity, we knew what was expected of us, at such a moment.

—next to this speech—

Some of you may be frightened by the future I just described, and rightly so. There is nothing any of us can do to change the path we are on: it is a huge system with tremendous inertia, and trying to change its path is like trying to change the path of a hurricane. What we can do is prepare ourselves, and each other, mostly by changing our expectations, our preferences, and scaling down our needs. It may mean that you will miss out on some last, uncertain bit of enjoyment. On the other hand, by refashioning yourself into someone who might stand a better chance of adapting to the new circumstances, you will be able to give to yourself, and to others, a great deal of hope that would otherwise not exist.

—and, well, no, comforted is not a word I’d use. And anyway I’m pretty much positive it’s just me left thinking of Smoky Barnable, carefully planning a ponderous trip into town for supplies, and George Mouse’s fiefdom, his city block of intertwined apartments with their chickens and goats, and over and behind it all the despair of mad Russell Eigenblick, learning he’s not in the story he thought he was, and anyway it isn’t even his story—but mostly Fred Savage, that problematic, magical kuroko, making as much of a place for himself as he can in the interstices—

Some versions of proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fiction.

Elizabethan epics ride to the rescue of the beleaguered floppy comicbook:

One would expect this to come naturally to the Elizabethans because their taste must partly have been formed on those huge romances which run on as great tapestries of incident without changing or even much stressing character, and are echoed in the Arcadia and Færy Queen; any one incident may be interesting, but the interest of their connection must depend on a sort of play of judgment between varieties of the same situation. Thus there is a lady in the Arcadia, unnamed, who induces the king her husband to suspect of treason the prince her stepson; a magnificent paragraph explains all the devices by which this was achieved. Twenty folio pages later, after some one has told another story, the knights come to the castle of a queen called Andromana, who tries to seduce them and finally allows them to joust for the pleasure of watching, by which means they escape. It is with pleasure and some interest that one finds, on considering who her relations are, that this is the same lady, but it is quite unimportant; in both parts she is only developed enough to fill the situation. Bianca in Women Beware Women is treated very like this, only more surprisingly; she is first the poor man’s modest wife, then the Duke’s grandiose and ruthless mistress; the idea of “development” is irrelevant to her. Nor is this crude or even unlifelike; it is the tragic idea of the play. She had chosen love in a cottage and could stick to it, but once seduced by the Duke she was sure to become a different person; what is “developed” is a side of her that she had suppressed till then altogether. The system of “construction by scenes” which allows of so sharp an effect clearly makes the scenes, the incidents, stand out as objects in themselves, to be compared even when they are not connected.

—William Empson, “Double Plots”

The essence thereof.

I’m not by any stretch of the imagination a difference feminist or a gender essentialist; there are differences, yes, of course there are, but they’re scattered in bell curves that overlap to an extraordinary degree, and even if one’s labeled Man and the other Woman, well, you never meet Man or Woman, do you? Just people. Who happen to be. And so.

I’m not a gender essentialist: for it to be at all meaningful (as essence, mind, essentially), you’d have to convince me that any conceivable woman has more in common with every other possible woman that she could with any conceivable man, and vice-versa. There are differences, of course there are, but we have so many different ways to be different together; why waste all your time looking for the Men who Always Do This or the Women who Never Do That and risk missing the people that are all around you?

Blanket statements like that, when the polarities are Male and Female, end up inevitably circling around one particular This ’n’ That which Men Always and Women Never (well, Hardly Ever): SEX. And while they can seem relatively harmless on the surface, leading to silly head-scratchers such as—

Men are simple creatures. Protoplasms. It is a strange irony that a woman can pretty much get whatever she wants from a guy with no arguments and no disagreements—nothing but “Absolutely, dear” and “Whatever you want, honey”—by doing just one thing (but doing it two or three or sometimes four times a week).

(And while I don’t doubt there’s some folks nodding along with the beat out there, there’s a whole lot of other folks going now hold on just a minute, what?) —But such seemingly harmless homilies can twist all of a sudden into duties and expectations the rest of us never knew were in the social contract—

What if your husband woke up one day and announced that he was not in the mood to go to work? If this happened a few times a year, any wife would have sympathy for her hardworking husband. But what if this happened as often as many wives announce that they are not in the mood to have sex? Most women would gradually stop respecting and therefore eventually stop loving such a man.

What woman would love a man who was so governed by feelings and moods that he allowed them to determine whether he would do something as important as go to work? Why do we assume that it is terribly irresponsible for a man to refuse to go to work because he is not in the mood, but a woman can—indeed, ought to—refuse sex because she is not in the mood? Why?

—and what was a seemingly harmless stupidity has become a collectively punishing generality, getting uglier with every Men Do and Women Don’t twist until we end up clutching at Spider Robinson’s Screwfly:

We’re all descended from two million years of rapists, every race and tribe of us, and we wouldn’t be human if we didn’t sometimes fantasize about just knocking you down and taking it. The truly astonishing thing is how seldom we do. I can only speculate that most of us must love you a lot.

Now Tiptree wrote “Screwfly” for a reason, and people who said shit like that were definitely part of the unbearable wrong that fueled that particular pocket of outrage in her head. But the coldly horrible what-if of the story is precisely what if Men Always Did; what if there really is an US and a THEM and an unbridgeable gender war between. —It wouldn’t look like a John Gray sitcom, is what.

(Yes. I know: Black mollies. —I never said the idea doesn’t exist. I said it isn’t true.)

I’m not a gender essentialist, but—

(Ha ha.)

No, seriously. Or at least as serious as I want to be, whistling once more past this graveyard. —When I’m out and about with the Littlest Wookie (so named because of her fluting and hooting and not at all because of her furry back), I’ve noticed it’s always women who are smiling at me, nodding, saying hello and oh my and how cute. It’s always women who are suddenly stepping close to rub her head without asking. It’s always women, and never men.

(And before you tell me it’s because as a father strolling through downtown with a baby Björned I’m clearly good breedstock and willing to invest energy in my offspring which does something all unconscious-like to her uterus or maybe it’s her hormones which explains why, you should note the crucial grammatical difference between “women always” and “always women,” and start maybe questioning what you should have been questioning all along: my perceptions, and yours, and theirs. —I’m lying, for instance: the cashier who gave us a 20% discount on a hefty load of groceries because the Littlest Wookie was fussy was, after all, a man.)

Okay, babies, but how about salesmen? —In my job I see a lot of email ripped from a lot of corporate email accounts and let me tell you: salesmen? Hands down the worst for the nasty jokes and the porn and the shockjock photos. Saleswomen? Not at all.

So there’s that.

Pith from the comments:

So I commiserated with Julia over the whole having to read Twilight thing; she said, “oh, you really should. Feel for me, I mean. If Susan Pevensie wrote an Ann Rice novel…” —And would you look at the air now, full of glitter?

Appropriative.

This didn’t happen to me. It happened to a friend of mine who used to work at Powell’s. I’ve never worked at Powell’s. She was standing next to a display of Riverdance photobooks or stacking a display of Celtic Christmas photobooks or photobooks titled maybe The Dublin of Joyce, I don’t know, but anyway you get the point: stacks of grass that green and grey stone walls and smiling old folks in tweed and maybe a pint or two of the good dark stuff. Anyway there’s a customer, a black man, and he smiles and says Ireland, huh?

And she says, yeah, it’s always a bestseller, all this Irish stuff. —She usually worked in the red room; the books on Ireland would have been in the purple room. But this might have taken place in the orange room. I don’t know for sure.

Anyway he shrugs and says well Ireland, it’s kind of like an Africa for white people.

And my friend allows as how okay, yeah, she can see that.

And he leans across the stacks of books and says, thing is, most of us actually came from Africa.

I’m not going to link to it, the critical contretemps that’s USsed and THEMmed its merry way across LiveJournal (mostly), in part because I have read maybe a teaspoonful of it, in part because it is far more heat than light (my fingers scorched already by what little I read myself), in part because “linking” to it would require nigh-daily updates longer than this post will ever be, even accounting for all the posts and threads that have since been flocked up tight, in part because people I respect and even count as friends however internetty are saying inflammatory things on either side of the divide, but mostly because I haven’t even read the book whose discussion started? sparked? is the focal point? of the current fine mess, so I wasn’t going to say anything at all.

Still, these ripples still keep lapping even at the shores of my little backwater.

But if I say something like how it’s an incredibly dick move to say you haven’t read the book, it’s such an egregious example of X that you couldn’t finish the book, because I mean come on, how can you say something so surely without reading it for yourself, well, someone might say why should I have to read the book to have an opinion because X and anyway I never used the word egregious, why aren’t you engaging my argument?

And if I say something like how it’s an incredibly dick move to say if someone hasn’t read the book what business do they have stating such a divisive opinion about it, because I mean come on, one of the unstated goals of an undergraduate education is to be able to say things about books one’s never read, well, someone might say yes but their argument is wrong I mean X why I’d never, and anyway that’s ridiculous, and why aren’t you engaging my argument?

Which would leave me protesting that I’m not trying to engage any arguments, I’m just trying to point out that if your goal is to have a conversation then you’ve lost by opening with a dick move and if you’re just preaching to the choir well that’s fine but realize what you’re doing and don’t pretend otherwise, but that leaves me as the guy in the middle with the squashed armadillos saying on the one hand but on the other and anyway a mild and not-at-all-inconveniencing pox on both your houses, and no one likes to hang out with him.

And if I say the reason I’m not engaging any arguments is because I haven’t read the book in question, that might leave you with the impression you’ve sussed out which side I’m really on. But then I’d have to point out that the move in question as described sounds dicey as all get-out and I’d never attempt it myself and the earlier attempt that some have cited, which I have read, I’ve got to tell you didn’t work in my opinion, well, that might leave you with the impression you’ve sussed out which side I’m really on, and if so could you tell me? I mean would you look at the crazy on my face? Is that the time? Whoa.

None of which anyway is what I wanted to say.

What I wanted to point out:

This entire argument, about cultural appropriation and all the isms that implies, is raging around contemporary works set rather firmly in the genre of fantasy.

I can’t think of another contemporary genre whose tropes are so nakedly the fruits of cultural appropriation. Whose toolkit is so openly dependent on the tactics of cultural appropriation. —We go to write about the fantastic, and so we sauce our pastoral dish with a biting dash of Other, because what is more strange or fantastic than the Stuff from Beyond the Fields We Know? —And more: we appropriate our appropriations, cannibalizing the books our books are made of until Fantasyland begins to take on its own dim shape, with folklore and folkways we all agree on that nonetheless have never existed anywhere in the REAL world. Miles and miles of books and not a TRUE or AUTHENTIC moment in any of them, and how proud we are of that!

Because look at the beauty. Look at the power. Look what can be done with these tools. But look at the tools; look where they come from; look at what we’re doing with them, and what we’re doing it to. —That’s where the critical discussion needs to be.

(But it is! cry US and THEM. That’s exactly where we are! Weren’t you paying any attention? And anyway I think I made one too many dick moves myself to be able to take on the mantle of Reasoned Discussion, and also anyway, I haven’t read the goddamn book—)

Will no-one rid us of this truculent pundit?

I want to be good; I want to live up to the koan. But then I hear something so willfully, viciously stupid, so areal, something that does such violence to our already shredded discourse, something like this—

The New Deal—everybody agrees, I think, on both sides of the spectrum now, that the New Deal failed. The debate is over why it failed.

—and I get all Lewis Black again.

The trouble with Holbo’s Complaint (“I realize it is really a quite serious matter than the right-wingers have gone around the bend and apparently aren’t coming back”) isn’t that it’s hard on US to read their stuff without a sunny heart. It isn’t even that THEM ain’t coming back from around the bend ever at all. —To each their own, you know? If that’s what floats their boat, who am I to judge?

It’s that they’re determined to drag all the rest of us around the bend with them.

The site, with its ever-present Wikimania for lists, lists many scholars who have given up on the site, many more who are discontented, and only two who are happy with the status quo. The vandalism problem has received a lot of publicity, but that one’s actually fairly minor, or at least relatively fixable. More aggravating is “edit creep,” the gradual deterioration of a polished article by well-meaning but careless edits, and, even worse, “cranks,” which are classified with typical Wiki-precision as “parasites, scofflaws or insane.” And a crank can single-handedly destroy an article’s usefulness.

The problem is that Wikipedia forces its contributors to come to a consensus, and building consensus with a crank is a fool’s errand. Many of the departing scholars note the incident that finally brought them to leave; mine was a truculent teenager who refused to acknowledge that minimalist music was considered classical, because, as he put it, “it sounds more like Britney Spears than like Merzbow.” Let that sink in a minute. A person who insists that Einstein on the Beach, or Phill Niblock’s Four Full Flutes, or Tom Johnson’s Chord Catalogue cannot be considered classical because it sounds like Britney Spears is not a person one can seek consensus with. Because of that and his flippant rudeness I refused to argue directly with him, and appealed to the Wiki editors. Yet because of the Wikipedia policy about consensus, I couldn’t get around him, either. And when I checked the “Expert retention” page, I realized that this was not an isolated bit of bad luck, but that this recurring problem bars the dissemination of knowledge throughout Wikipedia.

Kyle Gann gave up on Wikipedia because of it. But giving up the body politic is a bit more difficult. A lie gets halfway around the world by the time the truth gets its shoes on, and that was before a professional corps of altheaphagei took up their stations outside its door, forks aloft. What do we do to beat it back? Must we each of us Epimenidean soldiers take up steel-edged rulers and station ourselves at the palaces of the pundits and whack their knuckles as they wax stupidic—

Oh. Hey. Army of Davids. Self-correcting blogosphere. Wikitopia.

—We will never be done with the long slow slog of the koan: word for word, person by person, dismantling the stupidity, alleviating the ignorance. The wood to be chopped, and the water carried; the dishes washed and the laundry done.

Still. It’s hard, seeing intellectual violence like this, wolves outside the door the way they are, not to want to punch someone in the face. (Or at least spit in their coffee.)