In Soviet criticism, terms come to you!

Catherynne Valente went on a mild tear about “speculative fiction” which itself went and garnered just about a hundred comments in the first hour of its existence. Apparently, people like jawing over jargon! Who knew?

What’s interesting, about the rant and its responses, is how subtly different everyone’s idea of speculative fiction is. Which, granted, is true of almost all genera, by definition (if people remembered the same they would not be different people; think and dream are the same in French). —Valente (and some, if not most) sees it as a failed attempt at a big tent, a fantastika whose clinical air of technical specificity (these fictions, and their speculations) renders it incapable of embracing the messy, ugly, gloriously squishy numinosity of fantasy as she is wrote. —Others, including, well, me, see it as—and maybe it’s the folk etymology I’ve concocted in my own head? See, when the New Wave came along, people started casting about for something to call the stuff that was inarguably in the same basic arena as science fiction but wasn’t, how you say, strictly scientific, was insufficiently hard, and so some folks started to call it sci-fi as a way of making the allegiance clear while downplaying the whole science aspect of it, but then Harlan Ellison threatened to punch them, so they had to call it something else instead, and they settled on speculative fiction. Which is fine enough at what it does, but what it does is kinda wishy-washy, has no convictions to lend it courage, and lets people like Margaret Atwood reify their own takes on McCarty’s Error (“To label The Sparrow science fiction,” he said in his age-old review, “is an injustice and downright wrong”) with their hairsplitting games of science fiction and speculative fiction: it’s the travesty of porn and erotica all over again. —Any genre distinctions that hinge on de gustibus questions of “quality” are worse than useless.

Anyway, there’s a lot of people unhappy with “speculative fiction” as a term, almost as many as are unhappy with “graphic novel” (and luckily speculative fiction even after all these years isn’t nearly so firmly rooted as that other ugly compound). But there’s still the question of what to call the stuff that’s obviously “science fiction” but that isn’t strictly speaking sciencey; how do those of us who do not wish to be punched by Harlan Ellison meaningfully name and situate something like Star Trek without drowning in eye-rolling trolls who simply cannot resist pointing out how wrong it is to have sound in space? —Well, you wear the original term down further: from scientifiction to science fiction to sci-fi to SF, which (sigh) is an acronym, and leads to ugly coinages like “SFnal,” but has the signal advantages of: being immediately recognizable; not insisting on science; not being “speculative fiction.”

So I mentioned as much, over on the Twitter, my preference for SF, and @catvalente immediately pointed out the silent F therein. —Which brought me up short; I’d never thought of speculative fiction as kitchen-sinking fantasy qua the phantastick: fables and myths and the very best magic aren’t speculations, they’re demands; not games of WHAT IF, but DAMN WELL IS. So I see no problem replacing speculative fiction with SF; they do roughly the same job for me; that silent F wasn’t silent but always ever elsewhere. —Yet of course there are going to be those who do try to make the term as inclusive as it pretends to want to be on the tin, and will be caught up short by its shortcomings. And so.

(Once more, I’m driven to mock an old XKCD strip:

(Hard sciences? Ha! Working with objectively measurable quanta is easy.)

—Where was I? Oh. Musing that maybe I shouldn’t be quite so sloppy with terminology when throwing these words about. —Not that I’m likely to get less sloppy, but I should at least point to the pier’s mission statement (or mission essay, we don’t really go in for pith in this sort of thing) in this regard, “Ludafisk”: critical definitions of such things as genres can never be necessary or sufficient; are, like tools, highly situational; therefore, like tools, are to be put down and taken up again as needed. I could, I suppose, be a little more clear when I’m switching from flat-head to Phillips, say. Try to be, anyway.

(I keep kicking around a classification or hierarchy of terms, of modes, say, for SF and fantasy and horror considered as part of the triskelion; of idioms, referring to SF furniture or fantasy furniture, working with ray-guns-and-rocket-ships or rings-and-swords-and-cloaks, of genres being those contractual obligations such as steampunk or urban fantasy. But I keep resisting. So pretend I said nothing.)

—I would be remiss to those of you who follow along via RSS if I didn’t point out that in earlier entries in this occasional series old friend of the pier Charles S has been doing a yeoman’s job of chiding and chivvying and generally teasing the most interesting bits out for further consideration. So.

See, when you assume—

I wonder how much of the blame for things as they are (for many and varied values of things) might not be laid at the nigh-ubiquitous feet of the first-person smartass.

Vive la différence.

Trouble with Ted Chiang’s seemingly pat differentiation is most stories by construction must take their protagonists personally, and see them as special snowflakes: they are, after all, the people whose story is being told, without whom the very universe would not exist. (Think a moment how so much SF ends up as fantasies of political agency. There’s the storyable, world-shaking stuff!) —I like Jo Walton’s better: fantasy’s the stuff we know, in our bones, very much because it isn’t real; SF is that much harder because every jot and tittle you set down must always be checked, and checked again: like anything else that’s solid, science never stops melting into air…

It’s all her fault!

Via a one-off link over at Alas, an update to pronoun-sexing: apparently, Anne Fisher’s the one who first advocated “he” as the gender-neutral pronoun for English, upset as she was over numeric inconsistencies with then-popular “they.” —Or, well, maybe not.

Few, and carefully considered, and he broadcasts them like a beacon in every weather.

Martin Seay (of the Ke$ha essay linked above for the next little while) has written other things, of course; of course he has: he has a blog! —Today I read this longer piece on Norman Rockwell (and Spielberg, and Lucas, and a whole host of somethings else), and if you have a few minutes cleared at some point or other in the next little while, I urge you to do likewise.

You can add up the parts;

you won’t have the sum.

So you can anyway imagine the grin on my face when I tripped over Mendlesohn’s Corollary to Clarke’s Third Law:

Any sufficiently immersive fantasy is indistinguishable from science fiction.

Problem being she’s talking about immersive fantasy, and she classes or tends to class urban fantasy, the thing we’re pointing to, as intrusion.

—I’m gonna have to get into this, aren’t I.

Farah Mendlesohn sat down to grapple with the rhetorics of fantasy; she stood up with a taxonomy for organizing all of fantastic fiction, every last drop of it, based on the narrative strategies, the rhetorics used to establish the relationship between the normal, the disputable here of us, and the numinous, the ineluctable there beyond the fields we know—a sound basis for a system of describing (and not prescribing) fantasy as she is wrote, you’ll agree. (—What else is there?) —Her taxonomy, then, proposes four means whereby this relationship is inscribed, interrogated, upended and maintained:

- the portal/quest, in which we go from here to there;

- the immersive, in which there is no here but there;

- the intrusive, in which there comes here and must return;

- the liminal, in which there was here all along.

So. Four. (With yes an implied fifth, and an obvious sixth. —But for now, four.) —Why only four? Why these four? —Well.

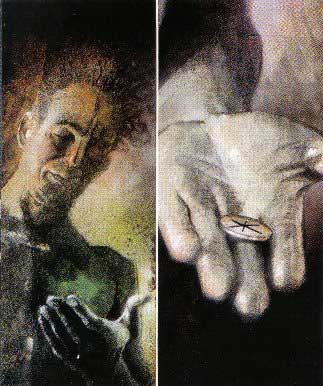

A while back I found myself idly toying with ways to structure and organize sexual imagery, energy, symbols and roles, flows of power and expectation, something a step or two beyond the brutally stupid dichotomy we’re mostly stuck with, the masculine, the feminine, which all too often boils down to the merely phallic. —Why, even Freud, who thought long and hard about this sort of thing, once said,

if we were able to give a more definite connotation to the concepts of “masculine” and “feminine,” it would even be possible to maintain that libido is invariably and necessarily of a masculine nature, whether it occurs in men or in women and irrespectively of whether its object is a man or a woman.

And not all the handwaving footnotes in the world can keep me, even here in the comfortable lap of 21st century cisgendered heteronormative privilege, from calling that out as the most specious of bullshit, a definition desperately trying to maintain the worldview in which it’s relevant. —Nonetheless, he did, and it did, and look where it’s all gotten us: bros before hos, amirite?

Anyway. At about the same time I was re-reading Red Mars, and so once again got caught in the seductive grip of the Greimas semantic square:

Proposition S; the opposite of S; the negation of S; the negation of the opposite of S. No simple dichotomy, this! (And it’s just the first stage.) —What I ended up with, then, looked something like:

I tried to go with terms at once as suggestive and yet sex- (and gender-) inspecific as possible—wait, you’re saying, the four, what on earth does all this—with the penetrating, and the enveloping, I mean, any of us, male, female, straight or gay or polymorphously whichever, cis or trans or not at all partaking, any of us—fantasy, you’re saying, urban fantasy, what does this have to do with—we can all identify with penetrating, or enveloping (I almost went with swallowing, but that’s a bit too too, you know?), with being enveloped, with being penetrated; we can all see them as valid stances, as desires, as starting points each as proper as the other, right? —Seriously, you’re saying, what does this have to do with the urban fantasy as sf and that taxonomy you were, and I’m saying patience, watch, count it off, do the math, look at them over there, they figured it out—

It’s a trifle, is what it is, a toy. I mean, I trust it demonstrates how easily the brutally stupid dichotomy can be disrupted, but Christ, anyone who thinks about it half a moment can see that. —And yet it keeps coming back, doesn’t it? Men do this. Women want that. Way of the fucking world. —I mean look where little ol’ cisgendered mostly heteronormative masculine me put the penetrative end of things, huh? Proposition S. Look how everything else gets othered by that placement, with all the opposing and the negating. —“The power involved in desire is so great,” says Delany, responding to (among other things) that Freud quote above,

that when caught in an actual rhetorical manifestation of desire—a particular sex act, say—it is sometimes all but impossible to untangle the complex webs of power that shoot through it from various directions, the power relations that are the act and that constitute it.

Sex and sexuality, desire and power, it’s all too terribly complicated for simple logical constructs to contain. The models are all wrong and useless. You start to feel like Two-Face in the Grant Morrison – Dave McKean Arkham Asylum, weaned by well-meaning psychotherapists from the binary limitations of his ghastly decisive coin to the six-fold options of a die, multiplying the ramifications of every choice he makes up to the paralyzing forest of possibilities in a decision-making system based on the fall of a pack of Tarot cards—he pisses himself, unable to decide which way to turn. No wonder the brutally stupid dichotomy keeps coming back! It’s wrong, but at least it gets things done!

But: if we replace the sex with rhetoric—

Two sides, normal and numinous, here and there; the membrane between them (for how else could we tell the two sides apart, or that there were two at all? —Remember: the rhetorics each in their own way inscribe and maintain the relationship between the two, which depends upon that difference); the crack within the membrane (for how else could the light get in? how else would it all be storyable?)—just adjust which is where as you go and oh do let’s be blunt about it: we (along with the protagonist) set out from the normal through a portal on a quest to penetrate the numinous; we (along with the protagonist) are utterly immersed in the numinous as it envelops us; we (along with the protagonist) are intruded upon by the numinous as it penetrates our normal world; we (along with the protagonist) find the numinous enveloped within us, a tremulous limen within our grasp. —Take the portal/quest, the ur-fantasy for most of us, and set it in the role of proposition S; the rest, oppositions and negations, fall neatly into place.

Now one of the reasons I like arranging Mendlesohn’s taxonomy this way is it helps to visualize the pitiless logic of here and there that underlies it all (oh, but be careful! Such logic is seductive, and narcissistic: in love with itself it ignores anything that isn’t, and always risks turning brutal and stupid. There is an implied fifth, of course: everything else. And also the obvious sixth: none at all. But for now let’s stay in the square). But also: there’s the rhetorics primarily associated with each type:

- the portal/quest, as previously discussed, depends upon the didactic to tell the world as it is to its protagonist, and us;

- the immersive plays with ironic mimesis, its po-faced protagonist taking for granted things we’d find most extraordinary;

- the intrusive pushes and pulls its protagonist (and us), depending on latency (for irruptions must always prove short sharp shocks);

- the liminal eschews its protagonist and reaches up to us direct, through the dialectic between the reader and the work.

Take these, hang them about the square, and lift it all up to the next stage (I did warn you that the square was but the first move we could make):

And we start to see some of the moves hinted at in the taxonomy, the ways the sets can fuzz, and not: that the didactic of the portal/quest can shade to ironic mimesis, as its protagonist learns the ways of the world, and can reach even for an archly knowing dialectic with the reader, but can’t except in the very opening pages do much with latency—there is a door and we will go through it in this scheme of things. Why wait? —That the ironic mimesis of the immersive can always go didactic to drop some (forgive the term) science on us, or play with the latency of the wonders it cannot admit it delivers, but can never reach for that dialectic which breaks the seals between its there and our here, threatening the illusion of immersion. —That the latency of intrusion can use both ironic mimesis and a knowing dialectic in its arsenal of pushes and pulls, but can never come right out and and say what’s happening, flatly, and expect to pull it off. —That the liminal can use—must use—both latency and the didactic to keep us at once engaged and at bay, but would (ironically) find ironic mimesis too open and direct an admission of the wonders it’s always on the edge of revealing.

As, I mean, a for instance. Don’t take my word for it. I’m just fucking around at this point. —Christ, I haven’t even gotten into how this all does and doesn’t work with the Cluthian triskelion. —Mostly what I need for you to understand before we take our next step is this: that Mendlesohn sees the immersive school as having the most in common with the “closed” worlds of SF, which is what her corollary means, and why my grin’s provisional at best; that she classes urban fantasy as intrusion, as stories of push-me–pull-you latency, and thus not SF at all, at least not in that sense.

But—

As Mendlesohn herself notes (citing among other works Perdido Street Station,) an immersive fantasy can host an intrusion.

I’d argue in turn that an intrusion not successfully beaten back must then become an immersion.

Thus as to how it is that urban fantasy must necessarily be SF, you see—

This still isn’t about steampunk, dammit.

But via Jess Nevins I learn of Beyond Victoriana, dedicated to “multicultural steampunk and retro-futurism—that is, steampunk outside of a Western-dominant, Eurocentric framework.” —Updates every Sunday and Wednesday.

Anent the preceding:

I feel a bit sheepish over how I left the problem of steampunk, for all that this isn’t about steampunk, and won’t be, dammit; a bit glib, to toss off Íkaroi and asymptotes without acknowledging how any one of us worth our salt should take a fence planted and a gauntlet thrown like that: back up for a goddamn running start. —And I never should have linked to Catherynne Valente’s magisterial rant without acknowledging her morning after.

Still, do or do not; there is no try. Tripping over the gauntlet and faceplanting into the fence does nothing but bloody your nose and besides, the fence likes it. —And anyway I’ve got angels of my own to wrestle with. (The themes of seduction and colonization running just under the surface of urban fantasy, say.)

But:

(And I don’t yet know for sure quite what to do with this which is why it’s being stuck over here to one side as a parenthetical—)

There’s this thing Nisi Shawl didn’t say so much as allude to and play with, on a panel at the 2009 World Fantasy Convention:

What I said was that some critics had called cyberpunk a reactionary response to feminist science fiction. This is true. Specifically, I’m pretty sure this is something Jeanne Gomoll, among others, theorized about.

I brought up this point because though I don’t personally believe that cyberpunk was a reactionary response to feminist science fiction a) It’s an interesting premise to examine; b) Examination leads me to think that while cyberpunk and the cyberpunks were not antagonistic to feminist science fiction, part of the media hype surrounding it was an attempt to find something, anything to look at other than feminist science fiction; and c) Parallels can be drawn between the popularity/commodification of cyberpunk and the popularity/commodification of steampunk in relationship to, respectively, feminist science fiction and speculative fiction by POC. Also, I was being somewhat provocative, which I think is kind of my job on a panel: to entertain as well as educate.

This isn’t about steampunk, dammit; I’m not trying to kick it once again. (Here, have some lovely steamy boosterism from Nisi Shawl, a glorious backing-up for a good hard run at the damn thing.) —It is an interesting premise to examine—note the elision to genre-as-marketing-category in the above, which is where marketing dollars pool, instead of fears; but remember that marketing dollars have fears of their own.

But this is about urban fantasy, and while I know for a goddamn fact the way only someone who’s lived through the past forty years can know that history doesn’t progress, not any more than evolution does, that any narrative here is necessarily constructed by a guiding, editing, distorting hand without which you have just a bunch of stuff that happened, and while I’d never presume to call urban fantasy qua urban fantasy in any way a feminist genre—it is more concerned, much more fundamentally concerned with gender and interpersonal relationships than cyberpunk ever was, and while I’d never make the assertion that the leather pants and the elves in sunglasses and the vampire CEOs and etc. and etc. are in any direct or meaningful way an offshoot of or outgrowth from or improvement on cyberpunk—don’t get distracted by the dam’ furniture—

Still. The idea won’t leave me alone, is all I’m saying.

But anyway the urban fantasy crew for whatever bucks it might bring in is still I gather second class in the Beowulf game; fangfuckers, they’re called, and paranormal romance is said too often with a sneer; I know, I’ve felt it on my own lip more than once. —It’s late. I’m digressing. There’s other moves to make. I need some sleep.

Obversity.

There’s every now and then the occasional moment you can look back at, point to, a specific slice of spacetime where you can say there, that’s where the science dropped. —A while ago Felicia Day went and said this about a book by M.K. Hobson, friend of the pier:

And when I saw that I said to myself now waitaminute what on earth is she doing calling out a steampunk novel to urban fantasy fans? Because I mean on the one hand, goths who just discovered brown. On the other, leather trousers half-undone. But there came a tapping on my shoulder and a light was glaring in the corners of my eyes and when I turned to look I was struck dumb at that very instant by the insight:

Steampunk is the fantasy to urban fantasy’s SF.

You remember what I told you about how we were gonna abstract it up and out? How you shouldn’t get distracted by the furniture of swords and rings and rocketships, or zeppelins and tramp stamps? —Yeah. Like that.

In this book I argue that there are essentially four categories within the fantastic: the portal-quest, the immersive, the intrusive, and the liminal. These categories are determined by the means by which the fantastic enters the narrated world. In the portal-quest we are invited through into the fantastic; in the intrusion fantasy, the fantastic enters the fictional world; in the liminal fantasy, the magic hovers in the corner of our eye; while in the immersive fantasy we are allowed no escape. Each category has as profound an influence on the rhetorical structures of the fantastic as does its taproot text or genre. Each category is a mode susceptible to the quadripartite template or grammar—wrongness, thinning, recognition, and healing/return—that John Clute suggests in the Encyclopedia of Fantasy (338-339).4

—Farah Mendlesohn, Rhetorics of Fantasy

4. Clute and I have had a number of discussions over which formulation of the grammar of Full Fantasy to use here. Clute being Clute, the formulation has gone through several revisions, rethinkings, and renamings. In the end, and knowing this is not his preference, I have chosen to go for the most physically accessible formula; that is, the version in the Encyclopedia.

So I was working my way through Mendlesohn—remember Medlesohn? This all started as a sequence of posts about Mendlesohn—and hit that passage right there in the introduction and had to stop. A grammar? Of fantasy? Qua fantasy? What on earth was this thing, with its talk of stages, categories, wrongness and thinning, recognition and return? I didn’t (and don’t) have a copy of the Encyclopedia myself; Clute I knew only vaguely as a critic (and spoiler) of some renown; Mendlesohn doesn’t spell it out much beyond the above, and some tantalizing hints throughout the chapters on her own quartered circle—but she did pick the most physically accessible of the possible formulæ, right?

Well, at $150 a pop, not so much. —And yes the library has a reference copy, but easy trumps free every time: a Google or three, and there we were: a talk given in 2007, making this if not the vision or thinking or naming close to that which Clute might rather Mendlesohn have used, at least a candidate rather close in time to the composition of the above.

Go on then, read it. —Even though I’ll be summarizing (in my own idiom and for my own purposes), you’ll want it under your belt so you can see for yourself where my model of her model of his model gangs agley.

Just—remember, okay? All models are wrong—but some are useful.

Clute’s model—at least as presented in this talk—isn’t just a quadripartite template for fantasy, but a triskelion encompassing, well, everything: the fantastika, which is another way of saying /fantasy/ or «fantasy» (or «smoke», or /mirrors/): “that wide range of fictional works whose contents are understood to be fantastic.” —This fantastika is posited as a Dionysian return of that which had been repressed by the cool, composed Appollonian excesses of the Enlightenment; by 1700, Clute notes, (at least within English literature),

a fault line was drawn between mimetic work, which accorded with the rational Enlightenment values then beginning to dominate, and the great cauldron of irrational myth and story, which we now claimed to have outgrown, and which was now primarily suitable for children (the concept of childhood having been invented around this time as a disposal unit to dump abandoned versions of human nature into).

This stuff, this fantastika, “the irrational, the impossible, the nightmare, the inevitable, the haunted, the storyable, the magic walking stick, the curse,” (the rocket, the ring, the sword, the goggles, the guitar) are then pressed into service as a means of dealing with those world-changes wrought by the aforementioned Enlightenment, the geist haunting the Zeit, the “World Storm” in the title of his talk: the unchanging state of constant change brought on by the onrushing Industrial Revolution, the Singularity that has always already been happening for some time now. —Clute identifies three main modes of this fantastika as of the twenty-first century, and bemoans their names: Fantasy, Science Fiction, and Horror—modes, mind, not genera, not idioms, not category fictions, not rigorously defined academic exercises, but modes, each passing through or touching on four basic stages of story, each differentiable by the skew it brings to those stages, the way they roll through the fingers and trip from the tongue:

- Fantasy, as noted, begins in wrongness, proceeds through thinning, has a moment of recognition, and then returns by turning away from the world storm;

- Science Fiction begins with the novum, the new thing, proceeds through cognitive estrangement on its way to a conceptual breakthrough, and ends up in some topia somewhere, in the eye of the storm perhaps, or somewhere through it, past it, beyond;

- and Horror, which begins with a sighting, then thickens about our protagonists until it can revel in the moment when we cannot look away, and leaves us shivering in its aftermath.

Or, if I might boil it all down to a grotesquely simplified reduction: a rejection, a celebration, a surrender.

Are there problems with this model? Oh yes. How could there not be? Setting aside for a moment how easily and even treacherously the one mode can slip to another within the same story, passage, sentence, you start squinting too closely at the details; who among us has not celebrated their surrender to something rejected? (We are Legion; we contain multitudes.) —No, I’m looking at the kernel of it all, the bedrock assumed beneath our collective feet:

—given the obvious fact that only bad worlds are storyable—

And oh, but this is Crisis-continuity, this is someone always insisting the stakes must be higher, this is someone just stopping in the face of the problem of Utopia, this is why movies suck and television doesn’t and the difference between Marvel and DC and this is much too much to go into right now but most of all it’s wrong, I mean let them be mindful of death and disinclined to long journeys, yes, but for fuck’s sake they will still be storyable, will still have stories, stories I at least want to hear and see and read—

Oh but that’s a tangent. Excuse me a moment. Ahem and all that. —What I meant to say was problems aside the simple clarity that triskelion brings to any discussion of the phantastick (to use my own preferred bumbershoot) is a powerful explanatory tool: one can easily see now why Star Wars is fantasy, and Star Trek is science fiction, and how delightful it is to consider Last Night as a gentle, whimsical, Canadian horror film.

And steampunk, well: but here’s another place the model starts to break. —Oh it’s fantasy, all right, whether there’s zombies or not; it is a nigh-desperate attempt to return, to reject, to recognize, but look at what’s being recognized, look where we’re returning: we don’t want the world-storm not to have happened. We want to go back to when it all began and try to do it over again. To ride it out better this time. To restart that Singularity, to make sure we get the zeppelins, dammit, and the goggles, and all the adventurous history this thinned mean world of ours won’t let us have. —Steampunk wants a mulligan on the Industrial Revolution, because what if? What if we had?

(—But that also requires a mulligan on imperialism. Oh what if. What if we hadn’t.)

So it isn’t as simple as all that, this celebration of something rejected, this adamant attempt once again to duck some awful, ugly truths. Still I think the triskelion helps us catch a glimpse of why it is the Great Steampunk Novel’s an asymptote no Icarus has yet managed to brush.

As for why urban fantasy’s really SF, well—

QFMFT

“It’s a bit of a wonder to me that there are so many people who remain a-quiver with anger over the fading heyday of crit-theory jargon in the humanities when there are fields of professional training as chock-a-block with buzzwords as ‘strategic management’ appears to be.” —Timothy Burke

Ambit valent.

Looking over the last entry in this occasional series I am, well, flummoxed; it’s a long and shaggy mess, isn’t it, and what I’d thought was the crux of it all—the omphalatic hinge?—got rather lost in all the noise.

—Probably doesn’t help that I hadn’t the faintest idea what that hinge even was until I’d written over half of it.

The which being: this whatever-it-is-we’re-pointing-to, this urbane phantasm, this lupily dhampiric gamine in an Eddi and the Fey T-shirt knotted up to show off a tramp stamp, this genre is essentially a superposition of two (to me) wildly disparate concerns, approaches, skillsets, Anschauungen: on the one hand, the broadly generalized concerns of what you might call primary world fantasy, where rather than haring off through wardrobes after magic rings beyond the fields we know, one seeks instead to take what wonder-generating mechanisms might readily be to hand and attach them however slap-dashily to real and concrete pieces of the world about us; tipping over stones and peering around corners and turning on lights after everyone else has left to show us the stuff we suspected but never believed could be true, not like that—the very general sort of thing any fantabulist worth their salt’s been getting up to for the past several centuries, made special in this particular only because so many of us here and now live in these relatively new things called cities; look! What changes might they ring on all the old tricks in our packs!

And then on the other hand, Anschauung no. 2: the fears where genre’s pooled: the prickly relationships now between power (and violence) and gender; the ways in which those relationships have changed suddenly, or how we’ve suddenly noticed they’ve been changing all along—or haven’t, at all, despite what you might think, might want, might hope—and how all those changes, or those things that stubbornly refuse to change, upset all manner of privileged applecarts and unsettle—make storyable—so much that we yet unthinkingly take for granted when it comes to power and gender (and violence); look! What changes this might ring on all the old tricks in our packs!

—Changes which have been happening (or not yet been happening dammit) in no small part due to these relatively new things called cities so many of us have been living in lately. I mean, you put it that way and all.

I’m left thinking—when I look at it this way, from this angle, with this set of vectors in mind (who was it who used to talk about how there were too many notes that had to be played but couldn’t be blown through a horn all at the same time so instead you play them one after another really fast instead, an allusion of chords? Sheets of sound? Was it John Coltrane? Yeah okay never mind), what I’m left thinking of (again) is the Engineer and the Bricoleur—the differences between coolly designing a system from the top down, and shaggily building a system from the bottom up; clean clear processes and principles thought through and carefully set down against solving the immediate problem that presents itself with whatever’s to hand and then up and on to the next—there’s a dizzying gulf between these two approaches, these disparate Anschauungen; it’s hard to keep the needs and goals of both in mind at once, and maybe this is why I keep flipping the coin over and over in my hand, startled every time the other, different side’s revealed—but look! It’s all one thing! And yet—

Probably doesn’t hurt that William Gibson has been twittering up the distinction between genre and narrative strategy that was I think made about him and his work by was it Dennis Danvers? I think? —And yes, it’s specifically SF-as-genre versus SF-as-narrative-strategy, but let’s pretend for a moment we can generalize it, unpack any intent from its strictures and look at each one by the other for a moment because this distinction’s gonna become important and you don’t want to be tripping over the furniture of swords and rings and rocketships when we abstract this shit up and out, and for fuck’s sake let’s all be as charitable as possible when regarding the connotative sneers that inevitably attach themselves to genre whenever it’s teased out like this; there’s some value to the exercise I think if we all keep our hackles down—ain’t nobody here Docxtrinaire, okay?

Where was I? —Genre, narrative strategy; urban fantasy; wonder-generating mechanisms, power and gender, sex and violence; cables and snakes and pythia. Right. —If one approaches urban fantasy as a genre, as a category fiction, as a transaction between a writer and an emergent and self-organizing audience with certain expectations that actively seeks out the sort of thing it likes because it likes that sort of thing; if one wishes to maximize the return (of enjoyment, of feedback, of reader response) on one’s investment (because who wouldn’t), one’s going to take a look around at what went on before to suss out the processes, the systems, the rules or at least the common threads before one sets out to build one’s own, and looking about one would see Buffy and Anita Blake and Mercy Thompson and Jayné Heller and Kitty Norville because there’s the bottle and there’s the lightning and one would be ill advised to push too far beyond (there are rules; there is a process; the audience likes what it likes and will tell you if you listen): and so one ends up with a Strong Female Character who deals with a supernatural intrusion either openly or clandestinely with some nominally masculine, appropriated power—a Phallic Woman, to put rather a fine point on it—and as one merrily sets about storying the hell out of a wonder-generating mechanism built along these lines, one can’t help but subvert and uphold, interrogate and reify all manner of gender roles and the power rules that they imply.

And if one instead approaches urban fantasy as a narrative strategy, as a way of generating story by taking up old wonder-generating mechanisms and plugging them into whatever relatively new bits of the urban environment present themselves to see what might happen, well: a great deal has changed over the years and so a great deal must be changed without changing too much at all, and that’s one of the challenges to be relished, but nowhere more than in the simple fact that we all see men and women and whatever différence might yet be vived very differently now than we did when the songs were first sung and the spells were first cast and the monsters first ripped from the dreams that spawned them, and one can’t be honest to the characters who find themselves in such a framework without helplessly being drawn back again and again to subvert all those gender roles and the power rules that they imply, and also to uphold them; to reify and interrogate them.

Whichever way you turn, they make the world go round.

(And oh but there are whole universes of discourse I’m glossing over here. Every nut-brown phouka in the room just cocked an eyebrow as if to say oh yeah, hoss? What about race? And I shake my head, later, later, Christ isn’t this all big enough as it is for the moment?)

So let’s not pretend this blurry, loosely drawn bivalent ambit is in any way either necessary or sufficient, but it’s nonetheless helpful (or why would I bother?). —One of the minor problems that has bedevilled me in skating around the problem of URBAN FANTASY (to turn the neon sign back on for a moment) is what’s to be done with Charles Stross’s Laundry books? Because he’s merrily attaching wonder-generating mechanisms to all manner of urban settings, and yet what he’s doing clearly isn’t URBAN FANTASY, as any fule kno. —And for a while there I was handwaving it away with muttered strictures about unity of place or somesuch; now we can all clearly see it’s because he isn’t taking up that other prong, of power and gender, because he doesn’t have to: his wonder-generating mechanisms are drawn from the chilly, post-Enlightenment well of Lovecraft. —And so.

From winter to winter again.

“…in that narrow world between the hills, she loved the river most. It is here and going elsewhere, like a story.” —Greer Gilman sings her mother on.

I’m trying, honest, I am.

“…if you’re not careful you will talk about it,” says Ray Bradbury. “Get your work done. If that doesn’t work, shut up and drink your gin. And when all else fails, run like hell!”

What we talk about when we talk about what we’re pointing to.

Urban fantasy as a subgenre usually has a little bit of hard-boiled noir action going on, blending fantasy with the elements of a modern crime story. Here’s a body, in other words, or some other horrible atrocity, and now here’s a hero/heroine with a special magical doodad/heritage who’s going to avenge/solve the crime. That’s the super-duper simple version, and the umbrella term can cover much more, of course…but that should get you started.

So, I am finishing up writing and polishing a YA novel that I thought was UF. But now I’m starting to think it’s not. By strict definition, it is. The MC and fairies having adventures around London. But as a marketing category, it seems like UF might not really work.

Under normal circumstances, it would be considered a straightforward Urban Fantasy/paranormal romance: independent, capable woman pits herself against the supernatural, meets up with mysterious wizard with dark powers and great cheekbones, and sparks fly, at least when Death isn’t waiting around every corner. You know, the usual.

After doing some research on the genre, I wondered if most urban fantasy fiction is in 1st person or you can get away with close 3rd with alternating POVs, corresponding with chapter breaks and/or scene changes.

Urban Fantasy is really bookcover-based, and as a genre is really a mashup of fantasy and romance novels, and we’re still sorting out the schizophrenia of clichés that this has produced.

And, sorry, I appreciate why you might want Urban Fantasy to mean what it meant 30 years ago, and you guys have perfectly good arguments as to why it should, but in common conversation it just doesn’t.

—Artw

Urban Fantasy seems to me to revolve around the uncomfortable relationship between gender and power.

If ten people are talking about urban fantasy, they’ll actually be talking about six different things.

Carrie Vaughn for the win, and not just because she’s written a neat overview of how the thing we pointed to when we said “urban fantasy” shifted and changed when I wasn’t looking into a bunch of other things pointed to by a bunch of other people. —“Urban fantasy,” of course, is a genre, and genera—whether we’re talking about the flavor-of-the-season catch-as-catch-can shelving categories of agents and sales reps, or the (somewhat) more considered taxonomies of critical apprehension—well, they’re social objects:

…those [objects] that, instead of existing as a relatively limited number of material objects, exist rather as an unspecified number of recognition codes (functional descriptions, if you will) shared by an unlimited population, in which new and different examples are regularly produced.

—And so while it’s possible to quibble and snipe over this trope or that and whether it’s really part of how you think the thing you think you’re talking about works at this precise moment in time and place in history, you should never think you’ve actually defined the thing in question, not necessarily, not sufficiently, not at all—it moves when you aren’t looking, shifts, changes; while you’re otherwise engaged, someone else points to something else entirely, and here we are left talking past each other, the ten of us, about six different things. —At least.

So what am I pointing to when I say—

Well, Christ, what is it I’m saying, anyway? Urban fantasy? Low fantasy? Modern fantasy? Syncretic fantasy? Contemporary fantasy? Indigenous fantasy? —Well much as my own finger might rather prefer contemporary fantasy (actually, my finger might best prefer indigenous fantasy, as suggested by Brian Atteberry: fantasy “that is, like an indigenous species, adapted to and reflective of its native environment,” but Lord does that fast become a problematic term)—I think it’s clear; the game’s given away: vox populi and critical weight and a couple of filips and grace notes we’ll come to all compel me to walk over here and sit me down under the blinking neon sign that says URBAN FANTASY.

Despite those wags who insist the “urban” must mean that Little, Big isn’t what I’m pointing to and Perdido Street Station is. It is; it isn’t; all of these terms have their problems, even the milquetoasty “contemporary.” —But it’s urban we’ve settled on; urban it is.

So that’s what I’m saying. What is it I’m pointing to?

At the end of the nineties I spent a lot of time walking from an office on Park between Washington and Alder to an apartment on the same block as what would later become Robin Goodfellow’s house at midnight, at one in the morning, at two. My route to avoid busy Burnside took me through what we were only just derisively starting to call the Pearl, through the heart of what would one day become the Brewery Blocks, when it was still, y’know, a brewery, and at midnight or one or even two the glass bottles would be clink-clinking together on the conveyor belt that ran overhead across the street from one stage of the brewing process, in that building there, to the next, in the building yonder. And somewhere on one of the corrugated metal sides of one of those buildings there’s this thing, and I don’t know what it’s called, but it’s where the main power line comes in and it comes down the outside of the wall in a sort of pipe that ends in in several up-curled snouts like horns from which sprouts a thicket of much thinner cables that branch out to carry the power off hither and yon throughout the building. And sometimes there’s one that isn’t in use anymore, so there’s no cables sprouting, just those horns, upturned, empty, waiting. And walking past at midnight or one or two I saw them and I said to myself, I said snakes, I said pythia, I said oracle—

—and there she stood all of a sudden, sprung fully if not finally formed into the pinkish-orange streetlight: this Lori Petty-looking kid with spiky yellow hair and goggles pushed up on her forehead and black jeans and a white T-shirt with the sleeves ripped off and mismatched Chuck Taylors with duct tape on the toe, and one work-gloved hand was on her hip and the other was holding a glimmering baseball bat, and she very obviously expected those snouts to turn and talk to her—

Kip, meet Jo; Jo, meet the author.

But that isn’t the point, that little where-I-got-my-idea moment, and anyway I’m lying about it. Just a little. You can’t help but lie about something like that when you set it down (and of course I warned you I would). —No, the point is the moment just before, the moment when the thing there on the side of the building shivered, or could have shivered, maybe, if the light had been right; when a wonder-generating mechanism of fantasy reattached itself however briefly to something any one of us could see out in the world: cables; snakes; pythia: not a portal opening onto some secondary world beyond the fields we know, but something indisputably here and now: contemporary; indigenous; syncretic.

The only reason it’s urban is because so very many of us who make it and read it these days live in cities. (Or suburbs, yes. Or exurbs. Urban. Look at the words.)

So that’s what I’m saying, and that’s what I’m pointing to, but what is it I’m talking about? Any fantasy which draws its sensawunda from the here and now? Because that’s awful broad, isn’t it? And there’s nothing at all in there about noir or crime or hard-boiling anything or vampires or dhampires or werewolves or witches or undone leather pants or tramp stamps or cheekbones or a close 3rd with oscillating POVs or well anything specific, you know? —Yes, yes. And no, I’m not talking about something that impossibly broad. I mean, it’s definitely a thing, it’s a valuable distinction, but it’s an awful big circle on any Venn diagram you’d care to make. We should maybe focus. Look more closely where we’re pointing. Keeping in mind of course that nothing we say can ever be necessary or sufficient enough to define what it is we’re talking about, so we’re just fucking around, right?

So if we take a closer look say at Enchanted—

Yes, Enchanted, the 2007 Disney flick about the animated princess who falls through a manhole into 21st-century New York City—

Yes, it’s an urban fantasy.

Look, just watch this, okay?

See? Urban fantasy. —No, not because it takes place in a city. Not just. But because it takes something particular to a particular city—no, not busking, or not just busking, but—well, watch this—

I mean, this shit really happens in New York. The spectacular busking, the audience participation, the spontaneous musical numbers, the sort of moment that just doesn’t happen, not in the same way, in Harvard Square or on Maxwell Street or Pioneer Square or wherever it is in London that busking goes down. —And granted, Central Park isn’t usually full of pre-rehearsed Broadway players between roles, but that’s just part of what makes the movie moment transcendent (and scoff if you like, but silly, and overblown, and swooningly earnest, these things all transcend)—thus magical, thus fantastic, but a fantastic moment grounded and rooted in a very real place we all know or at least can get to, not just drawn from but indisputably of a very particular here and now. —Wonder, however clumsily, reattached.

(It works the other way round, too. —I read Folk of the Air years before I ever flew down to the Bay Area and rode BART out to North Berkeley and when I got out of the train and stood on the platform and looked around and the way the light soaked the air without ever quite falling and the dark hills over there and all the water that you couldn’t see left me stranded in Avicenna for a long and dizzying moment instead, with Julie Tanikawa about to ride by on her big black BSA. —The indisputable here and now, without warning, reattached to wonder.)

But remember that none of this is necessary to define what it is we’re talking about—Bordertown is urban fantasy beyond the shadow of a doubt, and yet rather firmly takes place in a city that doesn’t exist, or rather (and this is the key, though it’s still off thataway, on the edge of the fields we know) it’s variously every city the authors see it as and need it to be, patchworked, multivalent—nor any of it sufficient to so define. (So why are we talking about it? I don’t know. Passes the time?) —When I started thinking about these posts and this one in particular I figured I’d stop here, you know, rough out the idea that what I was pointing to when I said “urban fantasy” was anything of the fantastic in an otherwise recognizable place, and then I would’ve backed off and tried to knock that over from another angle, see what happened when it broke.

But that isn’t it, and it isn’t sufficient. It isn’t even a genre, not yet. It’s—an idiom, a loose collection of tropes, windowdressing; it’s too clumsy and loosely fitted a tool to use for any close-in work. (Hell, you could fit great steaming chunks of magic realism in that definition, and I think we all know that’s not right.) —So: more focus, more specificity, more—noir? More boiling? More cheekbones? More leather? More Glocks?

I mean I started kicking this around because it seemed to me there’d been a divergence between old skool urban fantasy and the paranormal romance that lines the supermarket shelves these days; because saying to myself that what I wrote was urban fantasy meant trying to imagine what Jo Maguire would look like in leather pants on the cover of a book her tattooed back to us all (and then bursting into laughter; “I thought it was UF, but now I’m starting to think it’s not”); because I thought I saw ways that television and comics and role playing games had helped shape and widen that gap, which fascinated me, and anyway I’m a sucker for roads less travelled and not taken. So I set up my oppositions and sketched out the common ground and started doing the spade-work necessary to figure out exactly which term I preferred and whether I agreed that indigenous fantasy is essentially a rhetoric of intrusion or immersion and while I was dithering about Daniel Abraham went and said, “Genre is where fears pool—”

—and see that’s what’s missing from what I would’ve been talking about, that’s why what I’d had in mind as common ground wasn’t a genre any more than SF is a genre, or fantasy, or superheroes. Genre is where fears pool. It’s the immediacy, the kick, the redlining engine that doesn’t leave you the luxury of looking back and seeing what you just ran over, and urban fantasy, says Daniel Abraham, seems to him to revolve around the uncomfortable relationship beween gender and power—

And that certainly isn’t sufficient, no, and it isn’t necessary either but nonetheless watch it all slide and slip and snap quite suddenly into place, Anita Blake and Buffy and Eddi and Farrell and Doc and Oliver and one could even start reaching down for some of the dimly glimpsed taproots like Conjure Wife and hey, like I said, there’s Enchanted at the other end with some self-consciously conversed Disney platitudes about princesses saving the day.

But that’s heady and it’s late and I’m dizzy and this has gone on long enough for now. I want to back up, come at this ungainly construct from another angle, try to knock it over. See what happens when it breaks. And anyway I think I need to take up Clute next. —So.

Further up; further, in—

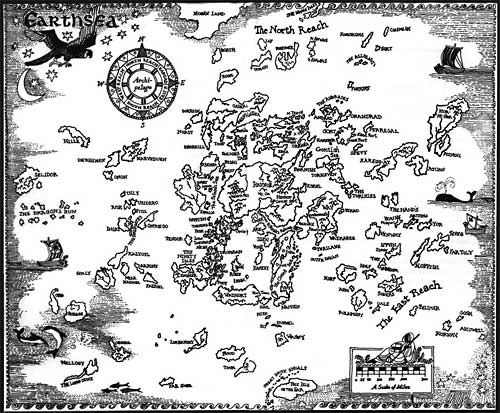

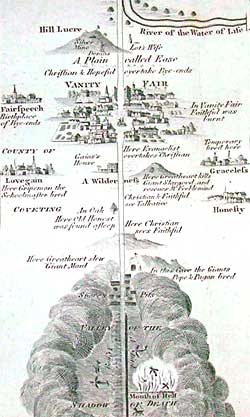

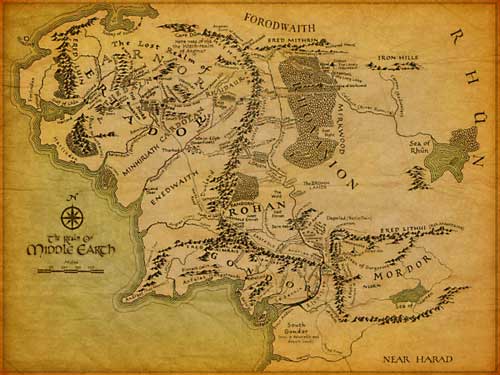

But! Baby steps. Easing back into it and all. —Maybe the business with the maps?

The portal quest fantasy, per Mendlesohn (as opposed to an immersion, or an intrusion, or a liminal, or whatever else, and trust me, we’ll get there), is a didactic idiom: one that takes its necessarily naïve protagonist on a tour of the otherworld with a garrulous guide or guides who brook questions almost as often as interruptions. “Fantasyland is constructed,” she says, and we should be clear, she means Fantasyland is constructed in the portal-quest fantasy,

in part, through the insistence on a received truth. This received truth is embodied in didacticism and elaboration. While much information about the world is culled from what the protagonist can see (with a consequent denial of polysemic interpretation), history or analysis is often provided by the storyteller who is drawn in the role of sage, magician, or guide. While this casting apparently opens up the text, in fact it seeks to close it down further by denying not only reader interpretation, but also that of the hero/protagonist. This may be one reason why the hero in the quest fantasy is more often an actant rather than an actor, provided with attributes rather than character precisely to compensate for the static nature of his role.

Which, okay, and now let’s skip ahead a couple of pages—

This form of fantasy embodies a denial of what history is. In the quest and portal fantasies, history is inarguable, it is “the past.” In making the past “storyable,” the rhetorical demands of the portal-quest fantasy deny the notion of “history as argument” which is pervasive among modern historians. The structure becomes ideological as portal-quest fantasies reconstruct history in the manner of the Scholastics, and recruit cartography to provide a fixed narrative, in a palpable failure to understand the fictive and imaginative nature of the discipline of history.

Flip back a page or two—

Most modern quest fantasies are not intended to be directly allegorical, yet they all seem to be underpinned by an assumption embedded in Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678): that a quest is a process, in which the object sought may or may not be a mere token of reward. The real reward is moral growth and/or admission into the kingdom, or redemption (althouh the latter, as in the Celestial City of Pilgrim’s Progress, may also be the object sought). The process of the journey is then shaped by a metaphorized and moral geography—the physical delineation of what Attebery describes as a “sphere of significance” (Tradition 13)—that in the twentieth century mutates into the elaborate and moralized cartography of genre fantasy.

—which paragraph ends neatly enough with—

In any event, the very presence of maps at the front of many fantasies implies that the destination and its meaning are known.

—and, well, yes, okay: I mean, you open just about any wodge of extruded fantasy product these days and yes, there it’ll be, the map, or at least it used to be that way; maybe it’s fallen out of fashion these days? —Doesn’t matter. The ghost of it’s damn well there. There’s always been a map.

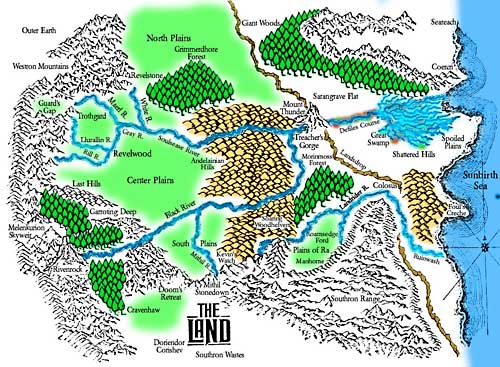

And maybe it isn’t too clear, immediately, on the map in Papa Tolkien’s tome, how the process of the journey is laid out, how it is exactly the geography’s metaphorized and moralized. But pull out some more maps, pore over them, look at how the Skull Kingdom’s always behind the Knife Edge Mountains—

—how the Soulsease River flows through Treacher’s Gorge and Defiles Course into the Sunbirth Sea—

—and you can start to see it; look more, look further back, scrub away the distractions of mountains and trees and lakes and look just at the map itself—

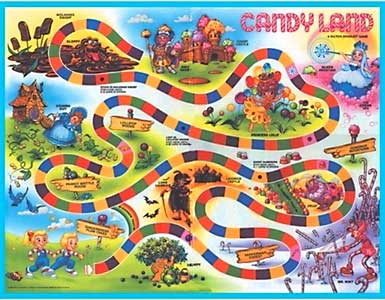

—and you can start to see the sphere of significance plain and clear, on which then the story of the quest of our hero(es) can be, well, mapped—

—a bildungsroman unspun in space, not time. You will go here, and have this adventure; go there next, and meet this companion; you will face physical hardship in the mountains, then inner turmoil in the deep woods, and if there’s a city, there will almost always be a seige, and a tower, and a coronation. Go and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again, and keep what you know of the story (of story itself, even) in mind (you know the story; the thing about this sort of thing is you’ve yes always already known it), it becomes clear that the destination and its meaning are known, are written there before you, that there was only one way it could ever have ended, once you started in the bucolic upper left; you had to sweep down and down to those snarling mountains in the lower right, and the city of Gondor gleaming there, where you might find your reward. —Didactic, fixed, moralized, metaphorized; cartography has been recruited, yes yes.

But—

Maps were my protonovels. I was reading Tolkien, and it was the maps as much as the text that floated my boat.

Mendlesohn, and this is important, is describing an effect of the rhetoric of the portal-quest fantasy. And it is a terribly important and I would even say o’erweening effect; she is not wrong to highlight it and draw protective circles about it thrice and thumb its forehead with penitent ash. The didacticism, the storyable past, the moralized geography, the protagonist as actant, the you-must-do-as-you-are-told-to-save-us-all (to reach the Celestial City, to redeem yourself)—this (if I might stuff it all into a singular word) is the supreme weakness of the portal-quest, and because the portal-quest is even now the supreme idiom of fantasy, is even now all of what most of us know of fantasy at all, this effect she’s described must therefore be addressed one way or another by every phantastickal book on the shelf.

But it’s hardly the intent of the naïve protagonist, the travelogue through fantasyland, the expository wizard, the map on the frontispiece. —Nor is it anywhere close to the only effect this furniture, these bits of business, might have on the reader, and the reading.

I’ve embedded images of these books because they offer, in various ways, some of the visual appeal which takes hold of readers of LOTR, The Hobbit and so on; Tolkien was susceptible to the paraphernalia of scholarship, to maps, manuscripts, the annotations which triangulate desire on such artifacts as objects of retrospection to a more heroic time—one constructed as real through the survival of such relics. For a certain sort of reader, scholarship is glamorous because reinforcing l’effet du réel.

The intent (an intent) is to take us readers by the hand and lead us from the world as it is out and away beyond the fields we know, and the simplest, easiest, most direct way to do this is to put fantasyland Out There and lead us through it, dragged along behind a protagonist who doesn’t know much more than we do, who must have stories told to them (and us) about the things they see, and because we are traveling about together in this other world, well, why not a map? That artefact of traveler’s journals ever since travelers began keeping journals. (Did every traveler keep a journal? I mean, all of them? How long ago did they begin, anyway? Were they really journals, or were they more reflections written long after the travels that spawned them? Or, y’know, propaganda, or marketing collateral, or—)

—To insist that history is multivocal, is an argument to be taken up and not a story that is dictated, is, well, is correct; to castigate this simple, brute-force technique for lulling a reader into the fields beyond as not living up to this basic truth of how we know what it is we know is, well, is also correct—but it overlooks the fact that the many and varied voices that carry out this argument of history, these arguments with history, are carried by books upon books within books echoing off books.

Most fantasylands are lucky to get just one.

And this is not an excuse, no. But it is a way out of the supreme weakness hobbling this idiom supreme: there’s absolutely nothing to prevent a writer from taking a protagonist and the reader bobbing along behind through a portal and on a quest that traverses an argued, arguable fantasyland, one where the questions one asks of the garrulous wizards, the interruptions one makes in the stories they try to dictate, are themselves important bildungstones, are themselves crucial steps on the road to the Crystal City of redemption and restoration.

(The trick of course is that the bedrock grammar of fantasy—that’s Clute, we’ll get there, trust me—would set you on a road to redemption and restoration, which irresistably implies that the questions asked will ever have final, true, correct answers; if you aren’t careful, you’ll just end up shifting the mantle of diktat from garrulous wizard to impertinent protagonist. —I never said it would be easy.)

But even if one doesn’t, even if the book one is reading hasn’t come anywhere near this ideal, well: it’s still a book. And the street will always find its own meanings in books. The most univocal, didactic, imperiously railroaded books can’t help but be polysemous; for fuck’s sake, they’re books.

And as for maps—

Recruit them all you like. Metaphorize and moralize until the very tectonic plates groan beneath the weight of your intentional fallacies. Make the road from Here to There through those Fields Beyond as straight and clear a track as you like. The thing about maps is no matter how simple or naïve they are they can’t help but hold more than you put into them. It’s the nature of maps. Even if it’s just the words Here there be Dragonnes. —Even if it’s just blank space surrounding the railroad track you’ve laid! Hell, sometimes blank space is the most evocative of all.

Go back and look at Papa Tolkien’s map again—

—and forget for a moment the too-obvious sweep of narrative laid out before you from Eriador through Gondor to Mordor. Haven’t you always wondered, lying on your stomach, map unfolded carefully carefully from the endpapers and laid out on the carpet before you, haven’t you always wanted to know what the beaches of the Sea of Rhûn were like, this time of year?

So. Yeah. Maps. Or anyway an intemperate discourse spawned by an offhand remark about maps, and their use and, well, misuse.

Baby steps. —It’s a start.

I’m going to leave you with one more map, an ur-map, if you will; the map, really, of fantasyland as she is wrote, or at least as I’m going to be playing with it for a bit, here:

Of course, a map really benefits from having a key. —It’ll come.

The Great Work.

The time my mother slapped me?

I was a junior in high school. Seventeen? Maybe. I don’t remember what it was I wasn’t to be allowed to have done, but I was complaining about it, bitterly, vociferously, rounding it out with the rising plaint of it just isn’t fair!

Life isn’t fair, she said, exasperated.

That’s no excuse! I snapped.

Pop!

What underpins all of the above is the idea of moral expectation. Fantasy, unlike science fiction, relies on a moral universe: it is less an argument with the universe than a sermon on the way things should be, a belief that the universe should yield to moral precepts.

Which isn’t what happened at all. —Oh, I was complaining about something; I was a teenager. And she’d told me more than once (but not that much more) that life just isn’t fair. And I wanted to say something in response, of course I did; I was a teenager. But if I ever managed to mutter anything at all I doubt it was so pithy. No, the time she slapped me I don’t even remember what she said, or I said. I just remember standing there, in the kitchen of the farmhouse outside of Chicago, the sting, the vague sick flutter in my belly and the half-swallowed grin of embarrassment, the acknowledgement that you know I’d probably deserved what I’d just got, but.

So I lied, just now. —But you know what they say about writers.

I’m not about to talk about it over there; over there, there’s whole words I can’t even spell out for fear of breaking—something. (Like the song says, as soon as you say it out loud they will leave you.) —But I have to talk about it somewhere. When I started to write it it was ten years ago and what we called the thing it was then was completely different than the thing we call by that name now. Used to be it was Eddi and the Fey concert T-shirts; now it’s tramp-stamped werewolves, and is that a bad thing? A good thing? A class thing? A get-off-my-lawn thing? Actually maybe not a different thing at all? —I don’t know, but I think maybe something got written out from under my feet, and it might be a good idea to figure out what it was before I land.

—And also there’s Mendlesohn, and Clute; Clute and Mendlesohn.

Which is not to say they’re wrong, my wanting to hash it all out like I want to. I mean, of course they’re wrong; they’re working with models. All models are wrong. But some are useful, and I haven’t yet figured out whether, or which.

Hence, the Great Work. Limned and primed.

Things to keep in mind:

The secret of courtesy.

“—I imagined that a man might be driven to despair by all the ugliness he had seen and want to see some unprompted dazzling act of goodness. I think this may not have been right. What I find is that if you deal with bad people for long enough you treasure even trifling acts of courtesy. If I go to a café and order an espresso, I’m charmed, disarmed, speechless with gratitude if the waitress brings an espresso.” —Helen DeWitt