Ironical.

“The model of irony which Wolff uses in understanding Marx is Socratic irony, which he defines as a statement made with two intended audiences, a naïve audience who assume that Marx intends the literal meaning of the statement, and a sophisticated audience who understand that Marx denies the literal meaning of the statement, and also understand why the naïve audience would be fooled. But this underestimates the extent to which irony is a rhetorical effect, taking the two audiences simply as given; what reason do we have to believe that there is such a naïve audience? The only reason we have to believe in the naïve audience is in the ironic writing itself; indeed, the naïve audience is purely imagined in order to produce the desired effect, in order to stage a confrontation between intention and literal meaning.” —Voyou Désœuvré

Dialing the phone like this.

Eh, you know. February. —Mostly I’ve been busy with the city, finishing off no. 17, thinking about the end game. There are quite a lot of plates spinning, aren’t there. Hadn’t really realized just how many till the last little while. Hmm.

I was intereviewed by Joey Manley (no relation) as part of a series he’s inaugurating on webserialists; lots of backstory, if you like. —And also I reveal the title of a putative volume three, about which there has been little to no comment, as yet.

And I should probably get back to the Great Work, shouldn’t I. (Further; talk; ambit; obversity; anent; parts.) —Trouble is, it’s time to take up the role of gender for real, and tackle the safe word, and my initial angle of attack’s over a year out of date. (Does that even matter?) —Trouble also is, Requires Only That You Hate has me instead musing over a thing that might compare Bakker’s Folly with a cheap Utena knock-off; that, however, would require reading Bakker, which has not begun well. (Petty? Perhaps.)

The other day Taran told me with the indescribable solemnity of a three-year-old that, while she was a cat, and Mamma was a cat, that I was a dog, and I’d have to stop meowing. I tried to explain how gender is performative, and meowing is a learned response, but I’m not sure it’s sunk in yet.

—On the other hand, presidents crawl on the table and have sharp teeth like beavers. So there’s yet hope?

There’s trees in the desert since you moved out, and I don’t sleep on a bed of bones.

“We clutch at the tough, dangerous heroines like Katniss because they offer an alternative to the bubbly romcoms and typically one-dimensional female characterizations. But it’s become too much of a black and white dichotomy that refuses the deeply flawed and all-too-human lead for the emotionally shut-off heroine who kills, and refuses to recognize any similarities in the two. I often hate to talk in terms of masculinity and femininity, but Blackwood is right that we tend to equate effectiveness with attributes that have been traditionally coded as male. I won’t go so far as to say Bella’s foibles are coded as traditionally female—they’re not. (As I noted above with my own memories—the most distinct weaknesses I see in Bella remind me of boys from the past, not girls.) But romance certainly is.” —Monika Bartyzel, “The Hunger Games, Twilight, and Teen Heroines”

The tragic result of a need unmet.

I forget how exactly it crossed my desk, who tweeted it, or retweeted it: “If you’d asked me last week who’d do better by Irene Adler, I would have been wrong.” —Which is an interesting sniglet to unpack, depending as it does on your awareness of the general tenor of both Sherlock franchises that sophomored within a couple of weeks of each other a couple of weeks back, and your familiarity with the œuvres of their respective auteurs, or at least the reputations of those œuvres: Ritchie’s “Women? What women?” bonhomie; Moffat’s polarizing brio, burning bright and quick through two seasons of Who and his first Sherlock outing. —And once all of that’s been taken to account, the intent of the sniglet’s clear: Ritchie’s inept dismissal of Adler from the plot of his second Sherlock (if not, technically speaking, the franchise) had already long since disappointed; the only possible surprise could come from Moffat’s being moreso. —But of course fandom being what it is, and polarizations being what they are, only someone expecting to be so surprised would have bothered to make such a statement. Once we might have expected more, they’re saying, but look! I’ve got a new benchmark to express our disappointment. —It’s not a true statement; it’s not even an ironic statement. It’s ironical. No one who could parse it could mistake its meaning. The only reason to have said it is so all could nod along.

Certainly, I nodded when I read it, before seeing the Moffat.

His ignorance was as remarkable as his knowledge. Of contemporary literature, philosophy and politics he appeared to know next to nothing. Upon my quoting Thomas Carlyle, he inquired in the naivest way who he might be and what he had done. My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the Solar System. That any civilized human being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the earth travelled round the sun appeared to be to me such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realize it.

“You appear to be astonished,” he said, smiling at my expression of surprise. “Now that I do know it I shall do my best to forget it.”

Never a big fan of Sherlock. Any iteration, really: he’s a bully and an asshole and his supposedly compensatory hypercompetence isn’t, so much: as a kid I never forgave him the above, and as I got older the blinkered, stratified, unbroachable classism his deductions required began to pall: how every charcoalmonger in the country must necessarily perform only the one job, the same job, in the same way, under the same conditions, that the characteristic sheen might properly be worn into the elbows of their only jackets, and the distinctive calluses of their trade manifest themselves on thumbs and index fingers, so that Holmes might once more demonstrate his skills. And his much-vaunted rede about the impossible and the improbable is nothing but a means of going wrong with ghastly confidence. —This inhuman student of humans who so haughtily disdains the humane: I suppose we had to invent him at some point, since he quite obviously doesn’t exist, but give me Dirk Gently any old day of the week.

The Ritchie Holmes amused and entertained (me, it should be understood; mileage, as ever, varies); big and noisy and engagingly designed, with preposterous plots that perform as plots ought in this sort of thing, and if I’m told the action sequences were choreographed to resemble the Victorian martial art of Bartitsu, who am I to quibble? —The chemistry’s the thing, and Downey and Law have it and to spare; I like my Holmeses manic, and my Watsons more sharpish than gruff, their fondness all but buried beneath the exasperation, and so. —I quite liked the Moriarty, far more than the warmed-over Lecter we’re given in Moffat’s. Mostly I like how in the background the whole urban world is constantly in the process of being built, modernity half unpacked from its shipping crates and left littered about the place. —And oh yes: I was indeed disappointed with his treatment of Adler, but mostly because the clumsy show-me-the-body “death” in the second film was terrible writing, and because I’d really liked Rachel McAdams in Slings and Arrows.

Moffat’s: I wasn’t going to bother watching it at first, but enough people said enough things about it that I did, and Cumberbatch and Freeman have chemistry to burn, and if Cumberbatch is a bit too controlled, Freeman’s exasperated enough to counterbalance it, and I was enjoying the first episode right up until it utterly ducked the sole responsibility a mystery story has, of solving its puzzle (for all the varied and possible meanings of solve, and puzzle): if I’d been watching it on the teevee I’d’ve thrown things at the screen (one does not throw things at one’s laptop). But something clicked, I guess; I watched the second episode, groaning the while, and also the third, though its mugging, pop-eyed Moriarty repels me. —But the chemistry; the sharp dialogue; the update game, which works more often than not; the way the current fad for sociopathic leading men in television lets them play appropriately nasty games with Holmes’s inhumanity; these I guess were enough to keep me coming back?

And the kick for deliberately not knowing the Earth revolved around the Sun didn’t hurt.

But: a relentlessly cruel Holmes grates, if you’re not all that fond of the character; and ever since the end of Jekyll I’ve been suspicious of Moffat’s ability to end anything: he’s aces at kick-offs, and wildly profligate with crowning moments of awesome, but all those improbably twisty plots end up just being, well, impossible to resolve. (I quite like how he solved this problem at the end of his first season of Who, by destroying corner and paint with one bravura fillip, but that’s the sort of thing you can only really do the once.)

So. That’s why I nodded along with the tweet (remember that tweet? This all started because of a tweet); but that’s also why I queued up “Scandal in Belgravia” and watched it one night when I should have been writing.

But like I said… fandom doesn’t do ambivalence. We want wholeheartedness. And if the thrust of the story is different than what we’re looking for, we’ll seize on only the bits of the text which tell the story we want to be told… the rest can just vanish.

Prepared not to be surprised at all by the benchmark that had been set, I ended up—well. Pleasantly surprised, by what I think I’d rate as the best episode of Moffat’s run (“Reichenbach Fall,” though one hell of a ride, was flawed, perhaps fatally, by its final shot). —And if I had to pick which of the two Irenes I’d say had done better by her Platonic, Akashic ideal, it’s no contest: I’d go with the flawed, compromised, pandering antiheroine over the tepidly inoffensive dispenser of plot coupons any old day.

—But blowing 1200 words to refute a tossed-off tweet to one’s own satisfaction is hardly debate, much less criticism. Let me do what I came here to do, which is commend to your attention ![]() jblum’s essay, “A Scandal in Fandom: Steven Moffat, Irene Adler, and the Fannish Gaze,” which does an able job of reading Moffat’s Irene as something more than a gross caricature, but more to the point makes some good points about all-or-nothing criticism that don’t boil down to the tone argument, or fannish defensiveness: being mindful of our needs going in; noting how the ways they’re met or left unmet distort our readings of whatever it is; taking this all into account. —Any text of sufficient complexity is incoherent; Fisking is always too easy.

jblum’s essay, “A Scandal in Fandom: Steven Moffat, Irene Adler, and the Fannish Gaze,” which does an able job of reading Moffat’s Irene as something more than a gross caricature, but more to the point makes some good points about all-or-nothing criticism that don’t boil down to the tone argument, or fannish defensiveness: being mindful of our needs going in; noting how the ways they’re met or left unmet distort our readings of whatever it is; taking this all into account. —Any text of sufficient complexity is incoherent; Fisking is always too easy.

(What was it, that met a need for me, or didn’t leave a particular need egregiously unmet? —I suppose it would be the moment when Watson and Irene are squaring off in that iconic power station, and he says—and I should probably interrupt to say if Watson never again has another mildy cod–gay-panic moment over his friendship with Sherlock it will be too fucking soon by half and then some I mean what the fuck year is this anyway, but nonetheless: the moment he says, “I’m not gay!” and Irene says, “I am. Yet here we are.” —Those moments when people might share an acknowledgement that what they are is so much more than what they’re capable of saying it is they are; when desire—no, scratch that, “desire” gets all confused with sex, which is fine for storytelling, but lousy for criticism, even one so muddled as this—when yearning does the anarchic thing it does, heedless of the cost; that tyrant, heart, wanting what it wants no matter what. —For whatever alchemical reason, it sunk home, this exchange, this moment, and all I’d let lead up to it; and thus my reading was distorted. —That tyrant heart.

(But enough already.)

Oh, wait! Found the original tweet. Sorry, Brendan.

Well there’s most of my opening paragraph shot to hell. —“Embarrassingly.” Huh.

Bitch; virago; she-devil; hellcat; sex-kitten; nymphomaniac; vamp;

or, Malicious, quarrelsome, and temperamental.

74%: that’s the math Goodreads hands me, when I tell it I’m on page 296 of The Magicians, and I’m not gonna bother to haul out the calculator to check it. I’m gonna pull the bookmark out of the book and put it back on the shelf in a minute, here. They finally made it to Fillory, but I just can’t be arsed.

And I’m going to tell you upfront what an unfair judge of this book I’d be, assuming I ever made it through, because how much I so desperately wanted to like it meant it’d never live up to what I wanted it to be. —But even weighting the scales with one hell of a thumb to account for that, this is one fucking careless book, and I’m tired, and there’s so much else to read.

I mean, I’ve been to a small liberal arts college. That’s where I matriculated. The whole dam’ college was the size of my senior year at high school, which would be a couple thousand people. There was this phone in the basement of the library, every now and then would make long-distance calls for free, you know? Or at least not demand the caller pay for the call themselves. —And when that happened word would spread the way it does about such things, and for the few hours that the magic held, a dozen people would be lined up at a time to wait to use this phone. (This was when long-distance was expensive, like international calls or something. A different age.)

So I get how you’d want to use an image like that, but stop and think: two thousand people, a few hours or a day or so at most at a pop, samizdata updates, an otherwise little-used phone in a library basement—we’re told that at Brakebills, with only a hundred select students, the one official phone that can reach the outside world constantly also has a line of a dozen or so waiting to use it. One-eighth the entire student body. Constantly. —Even as hyperbole it’s clumsy, because we can only even begin to parse it as hyperbole.

Oh but Kip you might say, stop. You’re taking this too personally; a chance image intersects with a memory you know in your bones; a bit of grit to become a dark, unwholesome pearl in your mouth alone. And maybe I’d agree, but it’s part of an overall pattern: of Brakebills being at once much too big, with too many rooms, too many teachers, too much stuff for only a hundred students, and yet so tiny and cramped there’s only five or six or so we even ever get to meet, if meet’s the right word. Or of the five Fillory books, which expand and contract as needed; if there are five books, say, one does not airily speak of things that generally tended to happen in the earlier books: there are only two earlier books. —Quod erat, for fuck’s sake.

We won’t be getting into how this carelessness fatally undermines whatever’s trying to be said about magic, and ethics, and morality; when you don’t seem to think you need a clear idea about something so real (and magic’s at least as real as religion, you skeptic you, so sit the hell down), well, you’ll never know which way to point it when it’s time to pull the trigger. I’d have to go back through it all to marshal the evidence needed, and as I’ve said I’m tired, and it’s late, and there’s so many other books.

No, the thing is this: this is the thing. 74%, page 296, Quentin the iredeemable asshole yes yes has just proved how manly he is by shoving Penny into a tree or something (allowing us, the Reader, a surging moment of we-would-never superiority tempered by a buried hint of oh-we-have recognition, yes yes), that’s not the moment I decided to drop the book. That’s just when inertia finally ran the flywheel down. No, the moment I decided to drop the book is terribly neatly encapsulable, right there on page 196, the 49% mark:

“Of course it matters, Vix,” Quentin said. “It’s not like they’re all the same.” “Vix” was a term of endearment with them, short for vixen, an allusion to their Antarctic interlude, vixen being the word for a female fox.

Seriously, narrative voice? Seriously? —Christ, get yourself to hell already.

“Fuck the exposition,” he says gleefully as we go back into the bar. “Just be. The exposition can come later.” He describes a theory of television narrative. “If I can make you curious enough, there’s this thing called Google—”

Talent is theft.

“Good artists copy; great artists steal,” said Picasso. Except of course he didn’t.

It was T.S. Eliot, who said, “Good poets borrow, great poets steal.”

Except, of course, he didn’t.

What T.S. Eliot said went a little something like this:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different.

Which, and we can get hung up on what is meant by “steal” and what is meant by “copy” and what is meant by “borrow” but that’s not important right now; it’s not as if there’s two discrete actions, and if you perform the one, you’re only good, but switch to the other and you become great. As if. Stealing, borrowing, begging, these are all fundamentally the same dam’ act; defacing’s in the eye of the beholder.

No, the takeaway is this: if you’re great—or seen as great—what you do will be read one way. If not? The other. —For he that hath, to him shall be given: and he that hath not, from him shall be taken even that which he hath.

On whether to fuck William Faulkner:

“It’s hard to explain to writing students that there are pods of very friendly, arguably moral authors who treat each other as if the literary life is led on a firing range. They meet you alertly, brightly drawing from natty holsters their own signs of power, rank and aid, and then requesting that you do the same. They aren’t evil, really, and the impulse behind it is so close to camaraderie it almost smells right. We all need help, and we all want to help each other, which makes the nuances of the transaction murky. Some people never see the problem at all and others treat every request like you’re asking for a toe of which they are particularly fond. In the end, parsing the aspirational nature of literary friendship is as much of a longshot as sexing the yeti.” —Glen David Gold

Gramarye.

Oh this Damien Walter post. —On the one hand it is very nice to see well it isn’t writing advice per se, but it’s nonetheless the sort of thing writing advice needs much much more of, and much much less of “cut the adverbs” and “don’t head-hop” and “spelling is important.” —What are you writing? How are you approaching it? What are the tools in your toolkit, and how might they be used to solve the problem? What the heck is the problem, anyway, and is conceiving of it as a problem even what you want to be doing? (What if you’re focused on the sound of what you’re building, and thus that string of adverbs is necessary for the swing?) (What if you’re making a point about universality and actively embrace a cacophonic leap from point to point of view?) (What if you’re making up a whole new slanguage as you oh but this is getting silly, the point is almost made—)

What if you want to write prose that plays with the grammar of cinema?

So maybe you want to cater to the more widespread literacy in cinematic grammar that Walter notes; it’s all about the reading protocols, after all. And maybe you want to mess around in the limen between the words you say and the scene they see; maybe you want to show and not tell. Maybe you want to have a narrative voice as flat and objective as possible because flat objectivity’s impossible, and that’s one of the points you’d maybe like to gesture toward. —So maybe I have a dog in this fight. The visible world is merely their skin.

But also, that other hand: any time you find yourself making essentialist arguments (“Novels dial the phone like this; movies dial the phone like this”), you need to run your check/wreck protocols, or you’ll find yourself stating things that just ain’t so merely because they neatly fit your strictures: the primary sin of fanfic, for inst, isn’t that it’s too cinematic, but almost precisely the opposite: in its attempt to exercise the authority needed to tell a story with someone else’s setting and these characters loved widely and too well, fanfic often indulges in interior monologuery far too drearily specific and on-the-nose in an attempt to demonstrate a basic competence with the material. And while I haven’t read enough Dan Brown to tell you just how cinematic he is, his failing most commonly mocked (probably because it’s the opening sentence of that book, and thus one doesn’t need to have read much further)—

Renowned curator Jacques Saunière staggered through the vaulted archway of the museum’s Grand Gallery.

—it’s no cinematic sin at all; the hilariously clumsy exposition of “renowned curator” is something only prose could fuck up quite like that.

Many of the sins Walter wishes to lay at the feet of this ersatz cinema are the sins of action-adventure fiction, which prose was committing long before cinema ate the world; which cinema caught, in large part, from the pulps it aped when it was starting out. —There are differences between the reading protocols of this sort of prose and that sort of cinema, sure, and it can be instructive to use the one as a way of looking at the other (in what manner, precisely, is The Wire novelistic? Show your work), but let’s be careful not to muddle medium and idiom and mode, while we’re at it. (To say nothing of genre.)

The primary difference between prose and cinema (beyond the obvious) is I think in time, and how each handles it; cinema (like theatre before it) no matter how achingly it might strive for universal generalities, must necessarily show you specific people doing specific things in specific places at very specific times. Prose, on its wily other hand, can say: “Monday morning staff meetings were always a chore for Willy” or “For the next week whenever she went to the coffee shop she saw the woman on the corner” or “And then everybody died.” —The narrow bandwidth of prose can’t begin to approach the wealth of incidental detail that makes up cinematic specificity without enormous slogging effort; most of the tricks and tips one needs to learn to tell stories and have them told with mere words, in fact, those reading protocols we’ve all had put in place, have everything to do with tricking us into thinking that specificity’s been achieved without us noticing (just as a great many of cinema’s tricks are all about forcing us to empathize with the saps up on the screen, bridging the vast gulf between their specificities and ours). —Now prose can give up its ability to turn on a dime, go large, sweep it all up, and constrain itself to cinema’s pinched and straitened lens (one can do anything one likes, after all), and this is neither a bad nor a good thing: the trick’s in how it’s done. How conscious is the author of what they’re giving up; how mindful of what they might reach for, instead?

And I would agree with Walter in this much, certainly: too many authors who do indeed give up a great many of prose’s tricks do so without noticing what they’ve lost, and what they might be doing instead with what they’ve got.

(The effect I think’s more noticeable when you compare comics and cinema: widescreen, decompressed superheroic storytelling is a far more conscious attempt to down tools half-understood and ape instead the things a more “successful” medium might do, and in this attempt comics is doomed to become nothing but stiffly rendered storyboards for the film we’d all rather be watching.)

Footnote.

Oh heck I was trying to remember where I’d read this for the previous and my Google Fu was weak. Maybe pretend it’s dropped between Frank Kovarik’s question and the Girls on Film, would you?

Female characters are traditionally peripheral to male ones. That’s why we don’t want to hear them chatting about anything other than the male characters: because in making them peripheral, the writer has assured the women can’t possibly contribute to the story unless they’re telling us something about the men who drive the plot. That is the problem the test is highlighting. And that’s why shoehorning an awkward scene in which two named female characters discuss the price of tea in South Africa while the male characters are off saving the world will only hang a lantern on how powerfully you’ve sidelined your female characters for no reason other than sexism, conscious or otherwise.

Niche marketing.

So apparently it’s our duty or something? As individuals of whichever gender or gender expression who find the Bechdel Test the bare minimum of acceptable standards?

“Hey A Lot Of Ladies,” began a mass email I received on Wednesday from Emily Bracken, a writer and acquaintance. She was forwarding a message from Kirsten “Kiwi” Smith, a producer and the screenwriter of Legally Blonde and The House Bunny, who has no professional connection with Bridesmaids but is nonetheless agitating on its behalf. “I know you get a lot of emails about donating money to worthy causes, but I’d like to draw your attention to one in particular: The Chick Flick,” Smith wrote. “It is currently on the Motion Picture Association of America’s list of Endangered Species and it faces extinction if we don’t act now.”

Urging everyone to buy tickets to the movie, Smith continued, “Let’s show the planet we are capable of queefing out some major box-office lady-power.”

And I mean it is not like there isn’t something to the dire sense of urgency behind this call to arms. To pluck a few points of anecdata from that New Yorker profile of Anna Faris that’s been making the rounds:

”In my experience, girls’ revealing themselves as candid and raunchy doesn’t appeal to guys at all,” Stacey Snider, a partner in and the CEO of DreamWorks Studios, says. “And girls aren’t that into it, either.”

“The reality is, I’m a dude and I understand the dude thing, so I lean men the way Spike Lee leans African-American,” says Apatow.

Seth Rogen thinks Faris is hilarious, is honest about himself: “If Pineapple Express had been about two girls, they wouldn’t have made it. And if I were a woman I wouldn’t have a career.”

To make a woman adorable, one successful female screenwriter says, “you have to defeat her at the beginning. It’s a conscious thing I do—abuse and break her, strip her of her dignity, and then she gets to live out our fantasies and have fun. It’s as simple as making the girl cry, fifteen minutes into the movie.”

But everyone likes a hot girl, if she’s not too successful or intimidating. Of Faris, a “leading agent” says, “What Anna has going for her, to be crass, is that guys want to nail her.”

Faris’s new film with Mylod, What’s Your Number, is about a woman who learns from a ladymag that if she sleeps with one more man than the twenty she already has, she’ll never get married. The studio executive debate over the number is instructive, as they wring their hands over how many would make the character an unrelatable slut.

Much of Backlash is dedicated to demolishing both the Bloom-Craig research itself and Newsweek’s further distortion of it—most famously, Newsweek’s preposterous claim that a single gal was more likely to be killed by a terrorist than to find a mate.

Oh wait! That last one isn’t from the New Yorker piece at all! That last one’s actually from an article written in 1999 about a book published in 1991 about a bunch of stuff that happened thirty years ago. —Sorry about that.

Anyway, Bridesmaids: it sounds like a funny movie and all and it’s getting great reviews, but a social responsibility? I mean really? The fate of big-budget Hollywood films starring women—well, white women—well, white women of a certain narrow set of socio-economic classes—I mean all that really hinges on whether or not we troop out this weekend to put money in Apatow’s pocket? (Well. And Wiig’s. And McCarthy’s. And Feig’s. And Universal’s. And—but I’m trying to make a rhetorical point, here.)

@carlafrantastic My worry about the Bridesmaids “it’s your duty” movement: Apatown planned it as part of their PR.

@kiplet That’s the smart money, yes.

@carlafrantastic Could also be, as u said, smart $. He was attacked for dismissing women, ventured to prove otherwise. Is this about ego, or virtue?

@carlafrantastic or does it not matter?

@kiplet What was that Twain bromide? No good or bad actions, just good or bad results of actions?

@carlafrantastic Somehow, the Bridesmaids “it’s important” movement makes me feel more used than empowered. And, I’m still going to go see it, ASAP.

The thing that didn’t occur to me until later, the reason that Salon piece, this whole campaign, had left me with a nagging deja vu, is that I’ve heard this all before—

Because didn’t we, as geeks, all have a duty to go and see Scott Pilgrim vs. the World, to demonstrate there was indeed a market for smart and funny and inventively geeky movies that spoke to us?

And didn’t we as geeks have a duty to go and see Serenity, to demonstrate there was indeed a market for smart and funny and inventively geeky movies that spoke to us, and also to stick it to Fox for killing Firefly?

And I mean that hunger—that hunger to see something that looks like you up on the billboards in Times Square and in the commercials on heavy rotation on Hulu and the posters and the marquees—that’s a mighty goddamn hunger; it might at first blush seem odd to turn the act of buying a ticket to a movie into a duty, a social responsibility, but it’s at your peril that you mock the power of dreamstuff deferred.

But still. —A duty? —And anyway the geeks ate the world already, right? Lord of the Rings winning Oscars™ and D&D jokes on primetime television and in The New Yorker and all those comicbook movies and Lost, amirite? But it’s not enough; the good stuff withers on the vine; we’re told there isn’t any money in it and SciFi has to go SyFy and show a bunch of ghost-hunting talking-to-the-dead reality-show shit and we have to keep begging and Guillermo del Toro can’t get At the Mountains of Madness made.

And women—54% of the population—are in the same damn boat? —Well yes white women of a certain narrow set of socio-economic classes, but that’s still an awful lot of money on the table, going begging; but even so, it’s not enough: women, we’re told, will get dragged to men-movies by men, but men won’t go to women-movies, it’s all in the numbers, you know?

Oh but really if it were really all about the numbers and the money, then one of this summer’s comicbook movies would look a lot different:

To less than 100,000 readers a month the Green Lantern is a white guy—to millions of television viewers he is a black man.

So there’s that. —But there’s also this?

@carlafrantastic esp. as [Apatow] is also producing @lenadunham’s Girls.

Social responsibility; first world problems; seeing yourself; small steps? I guess?

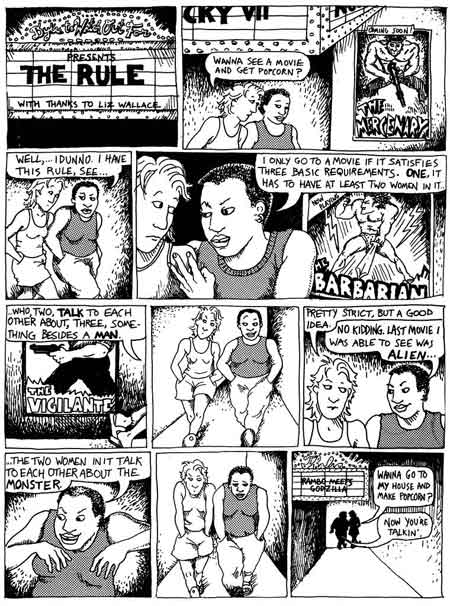

With thanks to Liz Wallace.

The crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women.

—Dan O’Bannon, Alien (née Starbeast)

FOOM! FOOM! FOOM! With explosions of escaping gas, the lids on the freezers pop open. —Slowly, groggily, six nude men sit up.

Having pretty women as the main characters was a real cliché of horror movies and I wanted to stay away from that. So I made up the character of Ripley, whom I didn’t know was going to be a woman at the time… I sent the people of the studios some notations and what I thought should happen and when we were about to make the movie the producer of the film jumped on it. He just liked the idea and told me we should make that Ripley character a woman. I thought that the captain would have been an old woman and the Ripley character a young man, that would have been interesting. But he said, “No, let’s make the hero a woman.”

—Dan O’Bannon, Cult People

[Veronica Cartwright] originally read for the role of Ripley, and was not informed that she had instead been cast as Lambert until she arrived in London for wardrobe. She disliked the character’s emotional weakness, but nevertheless accepted the role: “They convinced me that I was the audience’s fears; I was a reflection of what the audience is feeling.”

—Wikipedia, “Alien (film)#Casting”

FANTASTIC FILMS

Have you had any second thoughts about doing science fiction pictures in a row – first, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and now Alien?

CARTWRIGHT

Oh yeah. They were both screaming and running and crying films. But they were both very different.

FF

Are you worried being type-cast in the sort of role?

CARTWRIGHT

Well, I have to be very careful in picking my roles. I would like to do something comic next. I’m tired of crying. You know what I mean.

—Fantastic Films interview with Veronica Cartwright

What’s the Mo Movie Measure, you ask? It’s an idea from Alison Bechdel’s brilliant comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For. The character “Mo” explains that she only watches movies in which:

- there are at least two named female characters, who

- talk to each other about

- something other than a man.

It’s appalling how few movies can pass the Mo Movie Measure.

Julie from Portland, OR, kindly emailed us to let us know that lefty blogs like Pandagon have been discussing the Mo Movie Measure a film-going concept that originated in an early DTWOF strip, circa 1985. We were excited to hear that someone still remembers this 20-year-old chestnut. But alas, the principle is misnamed. It appears in “The Rule,” a strip found on page 22 of the original DTWOF collection. Mo actually doesn’t appear in DTWOF until two years later. Her first strip can be found half-way through More DTWOF. Alison would also like to add that she can’t claim credit for the actual “rule.” She stole it from a friend, Liz Wallace, whose name is on the marquee in the comic strip.

—Cathy, not Alison, despite what the author tag says

By the way, when I coined the phrase “Mo Movie Measure,” I screwed up—the character in Dykes To Watch Out For who says it, isn’t Mo!

She bears a strong resemblance to Ginger, but it isn’t a definitive resemblance. The strip is from before DTWOF developed an ongoing cast of characters, so it is hard to tell if Bechdel intended Ginger to have been that character from that strip when Ginger started appeared in the strip. The character in “The Rule” seems physically bulkier than I recall Ginger being, but that could be a shift in drawing style.

Also, the bit about the two female characters having to have names—which I thought had been in the original comic strip—was apparently added by me. Oops again.

That’s how these cultural ideas develop—it’s just a giant game of “telephone.”

The Mo Movie Measure—what to call it now?

/bech•del test/ n.

- It has to have at least two women in it

- Who talk to each other

- About something besides a man

A variant of the test, in which the two women must additionally be named characters, is also called the Mo Movie Measure.

—Wikipedia, “Dykes to Watch Out For#Bechdel_test”

If any studio executives are reading this, let me give some examples: Names are things like “Annie Hall” and “Erin Brockovich” and “Scarlett O’Hara.” Things that are not names include, to cite some credits from this year’s movies, “Female Junkie,” “Mr. Anderson’s Secretary,” and “Topless Party Girl.”

The wonderful and tragic thing about the Bechdel Test is not, as you’ve doubtless already guessed, that so few Hollywood films manage to pass, but that the standard it creates is so pathetically minimal—the equivalent of those first 200 points we’re all told we got on the SATs just for filling out our names. Yet as the test has proved time and again, when it comes to the depiction of women in studio movies, no matter how low you set the bar, dozens of films will still trip over it and then insist with aggrieved self-righteousness that the bar never should have been there in the first place and that surely you’re not talking about quotas.

Well, yes, you big, dumb, expensive “based on a graphic novel” doofus of a major motion picture: I am talking about quotas. A quota of two whole women and one whole conversation that doesn’t include the line “I saw him first!”

—Mark Harris, “I Am Woman. Hear Me… Please!”

I was struck by the simplicity of this test and by its patent validity as a measure of gender bias. As I thought about it some more, it occurred to me how few of the classic works of literature that I teach to my high school freshmen would pass this test: The Odyssey? Nope. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass? Nope. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Nope. Romeo and Juliet. Nope.

What’s wrong with me?

—Frank Kovarik, “Navigating the waters of our biased culture”

Female characters are traditionally peripheral to male ones. That’s why we don’t want to hear them chatting about anything other than the male characters: because in making them peripheral, the writer has assured the women can’t possibly contribute to the story unless they’re telling us something about the men who drive the plot. That is the problem the test is highlighting. And that’s why shoehorning an awkward scene in which two named female characters discuss the price of tea in South Africa while the male characters are off saving the world will only hang a lantern on how powerfully you’ve sidelined your female characters for no reason other than sexism, conscious or otherwise.

—Jennifer Kessler, “The Bechdel Test: It’s not about passing”

Then and back again.

Now.

I put the book in the envelope. I put the mailing label on the envelope. I put the cash card in the self-serve machine and get the postage and put the postage on the envelope. I take the envelope and I, aw, hell.

—I mean this isn’t happening now. This is happening about five or six hours ago. (Twenty-seven or so as I edit.) (My first-pass edits, anyway.) —What I’m doing now is I’m typing. I mean I’m not typing now. Or maybe I am but not this. Right now what’s happening is you’re reading this. I have no idea how long from this now that now is, so I have no idea how long ago by now the now was when I did all that.

But: it had to be done. I’d made a promise. Deal’s a deal.

So I put the envelope in the mailbox and sent it back the way it came.

Then.

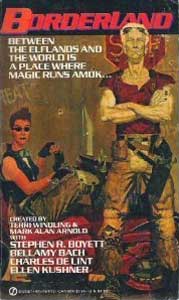

I took the book down off the shelf. Which one first, I’m not quite sure. —And I couldn’t tell you when it was I took it down. I’m pretty sure it was after I took War for the Oaks from the endcap display because mostly what I remember about the first time I saw War for the Oaks was the electric tingle sparking between fingertip and cover art as I reached for the damn thing; call it whatever the German portmanteau is for ohmygodwhatthefuckthislookscool. —Shock of the new, basically.  Which wouldn’t have been half as shocking had I already picked up Borderland and Bordertown, what with the elves and the motorcycles and the leather jackets and the rock ’n’ roll and all. —And while I remember the cover art for Borderland and Bordertown as a major factor in why I picked them up, I don’t remember that same spark; or not so potent, anyway. —But I could maybe have picked them up first. I was after all already a fan of the shared-world anthologies, Thieves’ World and Liavek and Wild Cards; here’s one more, with fæ punks; what’s not to love? —I think maybe I picked up Architect of Sleep after I picked up Borderland because Stephen R. Boyett, but I can’t be sure; I have a vague memory of being surprised that the one Borderland story (the postapocalyptic one, that feels like it’s in John M. Ford’s idea of the place instead of everybody else’s) was by the raccoon guy, but that’s a ghost of a wisp of a memory of a thought; untrustworthy. I could easily have picked up a book with a title like Architect of Sleep on a whim in those days.

Which wouldn’t have been half as shocking had I already picked up Borderland and Bordertown, what with the elves and the motorcycles and the leather jackets and the rock ’n’ roll and all. —And while I remember the cover art for Borderland and Bordertown as a major factor in why I picked them up, I don’t remember that same spark; or not so potent, anyway. —But I could maybe have picked them up first. I was after all already a fan of the shared-world anthologies, Thieves’ World and Liavek and Wild Cards; here’s one more, with fæ punks; what’s not to love? —I think maybe I picked up Architect of Sleep after I picked up Borderland because Stephen R. Boyett, but I can’t be sure; I have a vague memory of being surprised that the one Borderland story (the postapocalyptic one, that feels like it’s in John M. Ford’s idea of the place instead of everybody else’s) was by the raccoon guy, but that’s a ghost of a wisp of a memory of a thought; untrustworthy. I could easily have picked up a book with a title like Architect of Sleep on a whim in those days.  (Still would, actually. Wouldn’t you?) (Whatever became of the long-awaited sequel[s]?) (—Oh.)

(Still would, actually. Wouldn’t you?) (Whatever became of the long-awaited sequel[s]?) (—Oh.)

I don’t even remember if it was before I was in Brigadoon, or after. —What I can tell you is I’m sure I bought Borderland and Bordertown at the same time.

Pretty sure, anyway. —This was all a very long time ago, okay? How long? Let’s just say the shelf in question was in a B. Dalton’s and leave it at that.

Somewhat earlier.

Oh I was sunk already. I mean Tolkien, yes, and Lewis, and Heinlein and Asimov and Clarke, Alexander, Norton, Donaldson even, all of them hard on the heels of a diet of Matthew Looneys and Lewis Barnavelts and Bob Fultons and Furious Flycycles and Fat Bear Spies and Davids and Phœnices, but the thing that took off the top of my head was when Mom all unlooked-for brought home The Grey King. Magic that’s happening here, and now? —I mean, “here” was Wales, but it was a farm in Wales, and I lived on a farm, and oh who cares, I could make the jump for those songs, and that language like a secret code, and above all for the hint that something that big and that important could be just around a corner that I might see myself? Something made all the more real by how implacably and righteously unfair it was—

The rest of the books were secured post-haste. —I couldn’t sleep the night I turned twelve. I was waiting for the Old Ones, see. Maybe they’d missed me on my eleventh birthday. We’d been moving a lot.

Since then.

I was in Brigadoon, if I hadn’t been already. I graduated from high school. I saw Rocky Horror. I ran away from home the socially sanctioned way, to college; I dumped my high school sweetheart over the phone. I got an email address. (It was a much bigger deal, in those days.) I spent a summer in the Weaponshop of Isher, whose walls were held together with scotch tape; I got drunk, on beer, on wine, on White Russians. I tried acid, since I couldn’t stand smoking. I started drinking coffee in a diner in New York after seeing Crimes and Misdemeanors. I started smoking clove cigarettes. I dressed in nothing but black for weeks at a time and lost my heart beyond recall to my best friend’s sister. I saw Shock Treatment. I saw Liquid Sky. I saw Rare Air take the roof off Oberlin’s Finney Chapel. Twice. I found a Boiled in Lead album on CD. (It was harder to do, in those days.) I dropped out of college and got a job washing dishes so I could afford an 80-dollar-a-month walk-in closet that was so small I had to roll up my futon so I had room for my books. I found my heart again and sold the bass guitar I never learned how to play so I could cover rent. I was living with game designers, cartoonists, a proofreader, a botanist, a classicist, a computer archeologist. (I don’t think that’s what she ever called herself. But she made a killing, come Y2K.) Ten of us, in a five-bedroom house on a cul de sac? Somebody played me a Waterboys CD. I started dating a Jersey girl and when she moved in we swore we’d maintain separate bedrooms even as I was stashing my clothes in her dresser. Waiting for a plane in an airport in the middle of the country one of us turned to the other and said, we should get married, and the other one said, yeah, sure, only neither of us can remember which was which. We moved across the country on a whim, almost all ten of us. We got married, just the two of us, and then just the two of us got our own place. We bought a house. I backed into a career that had nothing to do with the writing I was starting to get done. We had a kid. We named her Taran, from the Lloyd Alexander books. We started buying more bookshelves for all the damn books.

I don’t know what happened to the Thieves’ World volumes. Whatever’s left might be in the attic of the house in Rock Hill? Along with that long-lost Dune Encyclopedia. The Wild Cards I’m pretty sure all got sold off. Liavek? A short while back I found another copy of the first one at Powell’s and I picked it up. The only Asimov in the house at this point is his Guide to Shakespeare which I really ought to give back to Dylan one of these days. The only Heinlein left is The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and Have Spacesuit, Will Travel. I should go get a copy of the White Hart tales; make a note of that. The original Coopers are long since lost, which is a damn shame; the old skool art direction kicked the ass of everything that’s come since; but I’ve got them on the shelves of course, along with Tolkien and Lewis and Alexander.

War for the Oaks? Bordertown? —Those books, the very ones I pulled off those B. Dalton’s shelves, tattered and worn, beat to hell, really—travel-stained, as it were—they’re up on the shelf above me as I write this. —Borderland ganged agley at some point in all that, but two out of three ain’t bad, right?

I should maybe see about replacing it.

A couple of weeks ago.

I was checking LiveJournal between Russian DDoS attacks (like you do) when I saw that ![]() janni had just posted the following:

janni had just posted the following:

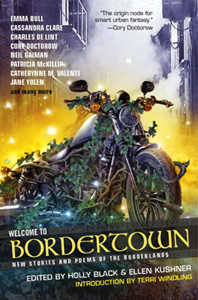

If you’d like to borrow Welcome to Bordertown, and you’re willing to commit to both reading it in about a week and to them talking about it somewhere online, leave a comment below. I’ll mail you my copy, and then when you’re done, you’ll mail it back to me, and I’ll send it on to the next person on the list. (ETA: And will keep doing so until the book itself goes on sale at the end of May, however many people that turns out to be, and at that point see whether it’s still in good enough shape to keep sending around.)

And you know Stumptown was coming up and the Spouse was trying to get her presentation done and her covers drawn and her book off to the printer which doubles me up on toddler duty and I still had about 4,000 words to write as it turned out and only that upcoming week to do it and yet—I didn’t hesitate at all. “For this,” I said, “I could make the time.”

Three days later.

I got one of those big Priority Mail envelopes dropped on my desk. —Good lord, this one’s a biggun.

So the first thing I did—I’d like to say the first thing I did was read Janni Lee Simner’s story, because one should be gracious to gracious hosts,  but the first thing I did (after I stuck a bookmark in where Simner’s story began) was read “Fair Trade,” by Sara Ryan and Dylan Meconis, because good friends had made it to the Border, and because, y’know, comics, but mostly because I had to see the Dicebox poster hanging on the wall in the Dancing Ferret. And there it is, and there’s Farrel Din, and Alberta’s Last Thursday art-walk fits right in on Carmine Street; how weird, to find a bit of where I am now in a place I haven’t been back to in years. —And then it’s on to Janni’s piece, “Crossings,” which plays a mean little game with Team Edward, and Team Jacob, and the neatly deflatory resolution of Team Jacob is one of those things you can only do in a shared world like this: borrowing somebody else’s character whose hard set-up and expository work has already been done elsewhere in that somebody else’s story, so all you have to do is use ’em, make your point, and let ’em go back about their other elsewhere business. —So then it’s on to Will Shetterly’s story, “The Sages of Elsewhere,” because Wolfboy, because you have to check in with the folks you used to know back in the day, see what they’re up to, and he’s running a damn bookstore now. —Somebody’s getting older.

but the first thing I did (after I stuck a bookmark in where Simner’s story began) was read “Fair Trade,” by Sara Ryan and Dylan Meconis, because good friends had made it to the Border, and because, y’know, comics, but mostly because I had to see the Dicebox poster hanging on the wall in the Dancing Ferret. And there it is, and there’s Farrel Din, and Alberta’s Last Thursday art-walk fits right in on Carmine Street; how weird, to find a bit of where I am now in a place I haven’t been back to in years. —And then it’s on to Janni’s piece, “Crossings,” which plays a mean little game with Team Edward, and Team Jacob, and the neatly deflatory resolution of Team Jacob is one of those things you can only do in a shared world like this: borrowing somebody else’s character whose hard set-up and expository work has already been done elsewhere in that somebody else’s story, so all you have to do is use ’em, make your point, and let ’em go back about their other elsewhere business. —So then it’s on to Will Shetterly’s story, “The Sages of Elsewhere,” because Wolfboy, because you have to check in with the folks you used to know back in the day, see what they’re up to, and he’s running a damn bookstore now. —Somebody’s getting older.

And that’s another thing you only get with shared worlds, with proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fictions, and it’s a blessing and a curse: virtual world journalism: “I don’t know, it’s kind of like reading a newspaper. It’s not like the newspaper is inspiring, but you need to read it to see what happens.” —It’s hard sometimes to see the story qua story because you’re looking around in it, through it, past it for the bits and scraps of the larger, shared world beyond, and if something like Bordertown isn’t nearly so proprietary as the Marvel or DC multiverses, allowing individual stories the leeway they need to stand on their own merits, and voice, well—it isn’t nearly so persistent, neither: five collections of a few dozen stories, three novels, thirteen years between appearances: you’re hungrier, is the thing, for those scraps and bits.

So next it’s on to Emma Bull’s “Incunabulum,” because it’s not just characters and neighborhoods you want to catch up on, and damned if it doesn’t seem to me at least like she’s riffing a little Delany in the mix, with her declarative paragraphs, her blank Page inscribed by his wanderings about the city. —Then Nalo Hopkinson in “Ours is the Prettiest” goes and drops a whole new neighborhood (to me, at least): Little Tooth, and the Café Cubana, and Screaming Lord Neville, and the swirling madhouse stomp of the Jamboree suddenly never has not been a part of the Bordertown, even as she’s asking some pointed questions about whose magic exactly it is that gets reified by the world as it’s been in these books; and in “Shannon’s Law” Cory Doctorow brings the goddamn internet to the Border, or at least an internet, and the way it’s cobbled together foregrounds the sheer joy of the basic, simple idea which has nothing to do with computers when you get right down to it—though it’s a joy that’s tempered by the melancholy inherent in the story of a kid running away to live out the story of the hardscrabble internet pioneer, a story that’s long since dead and gone out here in the real. —And somewhere in and among all that I read the lyrics to Jane Yolen’s “Soulja Grrrl,” which gets performed in the background in “Crossings,” and the “Borderland Jump-Rope Rhyme” (and is it only me who thinks of Louis Untermeyer when confronted with folklorist L. Durocher? Probably) and also Neil Gaiman’s “Song of the Song” and Delia Sherman’s “The Wall” and Steven Brust’s “Run Back to the Border” (because Steven Brust) but my favorite of the songs I think has got to be Amal El-Mohtar’s “Stairs in her Hair,” which spawns or was spawned by a metaphor in Catherynne M. Valente’s bracingly chilly “Voice like a Hole”—

—which, that move right there, that’s not something particular to a shared-world book, like borrowing a character or a setting somebody else has set up; that’s just the way art gets made, you know, the usual game of inspiration and allusion and homage, only with something like a shared world, a collective enterprise like this, you get to see it happen a little more quickly, a little more clearly, you get that giddy sense of play and camaraderie that Holly Black talks about in her introduction, of a bunch of writers sitting around writing and reading and one-upping each other, that idealized circus that any bookish youth with half a hankering to write themselves would want to run away to join, to finally hear, like Jimmy Fix-It does, heading into Danceland with the rest of Widdershins in “Welcome to Bordertown,” by Terri Windling and Ellen Kushner, that you’re with the goddamn band—

Soon.

The book itself drops in exactly a month; 30 days from now (as I write this, yes), Tuesday, the 24th of May. —I was gonna tell you about the contests various contributors are running, to win their advanced reading copies of the book, in case you couldn’t wait, but I took too damn long and the ones that haven’t ended already are ending today. —Still: Emma Bull was asking for ways to get there, and Nalo Hopkinson is yet soliciting menus for a king-hell meal to be cooked once you make it; go and read the entries already posted, because damn. (Oh wait there’s hope; there’s always hope; new contests keep being announced—)

It’s grand, it’s giddy, it’s gloriously stupid, it’s too earnest by half like all the best things you remember from then, it was terribly important to a great many people and I’ve no doubt at all that it will be again. In the thirteen years it Brigadooned itself away the phantastick ate up the world in a way it never has before, and the n00bs have been dreaming of rings and swords and elves in technicolors we never had back then; and it’s so much easier now with the internets and all to tell each other how to get there and what to do when you’ve made it. —If you’ve been before, you can go back. If you’ve never gone, then what the heck are you waiting for? Go! Go!

Centenary.

Happy birthday, Reagan (curséd be thy name hock-phthooie!). —It’s easy to laugh, isn’t it? Hollowly, bitterly, bleakly, ha ha:

But now, seven years later, Reagan’s inquisitorial zealots are being decisively rebuffed in Congress, in the courts (even the “Reagan Court”) and in the court of public opinion. The American people may have been deluded enough to vote for him, but they are clearly unwilling to lay their freedoms at the President’s feet. They will not say goodbye to due process of law (not even in the name of a war on crime), or to civil rights (even if they fear and distrust blacks), or to freedom of expression (even if they don’t like pornography), or to the right of privacy and the freedom to make sexual choices (even if they disapprove of abortion and abhor homosexuals). Even Americans who consider themselves deeply religious have recoiled against a theocratic crusade that would force them to their knees. This resistance—even among Reagan supporters—to the Reagan “social agenda” testifies to the depth of ordinary people’s commitment to modernity and its deepest values. It shows, too, that people can be modernists even if they’ve never heard the word in their lives.

—Marshall Berman, All That is Solid Melts into Air,

Preface to the Penguin Edition (1988)

But! But. Oh, oh, but:

The great critic Lionel Trilling coined a phrase in 1968: “Modernism is in the streets.”

—ibidem, motherfuckers; ibid.

The whipsaw’s back, in full force: on a bad day, oh Lord, most days I’m laughing, ha ha. —On a good day, though? From up there, up on a steep hill, with the right kind of eyes? I can almost see the glimmer of the goddamn Shining Sea.

Cold clear water.

“It comes to me that I won’t be able to explain this well,” says Vincent. —He’s wrong, of course.

Stupidity.

A catastrophic storm dumps feet of snow from Texas to Maine and sure as death and taxes here they come, out of the woodwork:

And it isn’t the mistaking of weather for climate, or anecdote for data; it isn’t that for every city currently experiencing record lows, whole continents were hotter than ever before this past summer. It isn’t that such extremes, such monstrous storms, are precisely what’s predicted by the theory he so sneeringly believes is evidently bankrupt. And it’s certainly not the unkillable zombie nature of these soi-disant arguments, how every goddamn time it snows Republicans build igloos on the Capitol lawn.

It isn’t even that @PatriotD66 couldn’t manage to cut and paste a simple hyperlink. —No, it’s cold in the mesosphere, and a piece of rhodium was once a few hundred picokelvins away from absolute zero, so Al Gore is fat and probably an atheist. Fuck you, liberals.

It’s a neat little essay in power, this scene from Mulholland Drive: Adam Kesher, the hotshot director, walks into the meeting with his swagger and his golf club and his insults and his bluster and despite all these overt displays of power never has control of a goddamn thing.

It isn’t the menace in the soundtrack, that he can’t hear, or the cuts to Mr. Roque, whom he can’t see. It isn’t how Mr. Darby and Ray and Robert Smith, the bit players, recite their platitudinous nothings with a deliberately overrehearsed sheen, playing their roles to the hilt but no further, refusing the risk of actual agency in the struggle that’s played out around them. It isn’t even how the Castiglianes sit there and stare and refuse to engage beyond sliding the envelope across the table and trusting the others to do what it is they want, though that’s close; this is the girl. This is the girl.

It’s what Luigi Castigliane does with the espresso, of course.

It’s a shockingly ugly moment, what he does. The revulsion that crosses his face after the sip, and then how he doesn’t spit it out but opens his mouth and lets it dribble down his chin to puddle on clean white cloth, his tongue licking out reflexively, his hands trembling as he pats his chin clean with the unstained end of the napkin. It’s all very physical, very grotesque, a body out of control of itself, driven to do what it’s doing. It’s a sign of weakness, and thus an overwhelming show of power.

—Because it is a show, isn’t it? It’s why he orders the espresso. It’s why he insists on the napkin. It wouldn’t matter if it really were the best espresso in the world; he’d still let it fall from his mouth, too overwhelmed to manage to spit it out. This is the power I have, he’s saying. I can do this terrible shameful embarrassing thing and there is nothing, nothing at all that you can do to take advantage of it. That is how much power I have over you.

Strength—the bluster, the golfclub, the insults, the anger—strength is for the weak.

Which is why they won’t stop, the ilk of @PatriotD66. They’ll just keep making these unkillable arguments, so easily defeated, even as the ice caps melt. It’s why Bill O’Reilly won’t stop telling his parable of the tides; it’s why Megyn Kelly doesn’t care whether what she just said was laughably demonstrably false. It’s the secret meaning behind that much-vaunted Rove quote about the reality-based community: this is the power we have over you. We can say these terrible shameful embarrassing things, these appallingly stupid things, and there is not a goddamn thing in the world you can do to take advantage of it.

Testing elephants.

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description; and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it—

A solid essay from David Campbell on the prickly troubles baked into the term “disaster porn” (or “development porn” or “poverty porn” or “ruin porn” or “war porn” or “famine porn” or hell just plain “porn”) when used to refer to depictions or representations of atrocity and suffering:

[Carolyn] Dean calls “porn” a promiscuous term, and when we consider the wide range of conditions it attaches itself to, this pun is more than justified. As a signifier of responses to bodily suffering, “pornography” has come to mean the violation of dignity, cultural degradation, taking things out of context, exploitation, objectification, putting misery and horror on display, the encouragement of voyeurism, the construction of desire, unacceptable sexuality, moral and political perversion, and a fair number more.

Furthermore, this litany of possible conditions named by “pornography” is replete with contradictory relations between the elements. Excesses mark some of the conditions while others involve shortages. Critics, Dean argues, are also confused about whether “pornography” is the cause or effect of these conditions.

The upshot is that a term with a complex history, a licentious character and an uncertain mode of operation fails to offer an argument or a framework for understanding the work images do. It is at one and the same time too broad and too empty, applied to so much yet explaining so little. As a result, Dean concludes that “pornography”

functions primarily as an aesthetic or moral judgement that precludes an investigation of traumatic response and arguably diverts us from the more explicitly posed question: how to forge a critical use of empathy? (emphasis added)

That’s the trouble with “porn” as a critical term: it’s been pwned by the pejorative.

For some reason the same day I got pointed at Campbell’s piece I thought of “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” for the first time in years.

Bruce Cockburn wrote the song in 1984, shaken by a visit to a Guatemalan refugee camp; apparently, it was his first explicitly political single. —A helicopter flies overhead, everyone scatters, and he wishes he had a rocket launcher: “I’d make somebody pay,” he sings, and then “I would retaliate,” and then, “I would not hesitate,” and finally, “Some sonofabitch would die.”

Canadian radio apparently used to fade out just before that last line.

Anyway, I’d never seen the video before:

And while I’d never call it pornography, and I don’t for a moment think it in any way creates an incurable distance between subject and viewer or leads to compassion fatigue nor do I see it at all as a threat to empathy or as something to dull our moral senses nonetheless: there is something unpleasant going on in that video and what it’s doing, what it did.

Disaster tourism, maybe? Atrocity holiday? —Oh to his credit Cockburn himself insists the song is “not a call to arms. This is, this is a cry…” And the video does indeed highlight—well. His impotence? His frustration? His embarrassment? As it keeps cutting back to him, singing with a vaguely pained expression in those theatrically smoking ruins. Goddamn I wish I could do something. Man if I had a rocket launcher. What fury I would wreak to help you all. Would that I could.

And I just keep thinking of what it was the Editors said: oh but you paid your taxes. Would that you had not. —Oh but Mr. Cockburn’s a Canadian. And that’s an American-made helicopter in that opening lyric, isn’t it.

If I had to functionally describe pornography, this elephant in the rhetoric? —Well. I’d always thought I’d copped it from Kim Stanley Robinson, but damned if I can find the passage in Gold Coast where I thought he’d laid it out. But: any work that stimulates an appetite without directly satisfying it, that tacitly but openly acknowledges that’s just what it has set out to do, that fulfills an agreement between artist and audience to appeal to this metaneed, to satisfy the need to need to be satisfied. And there’s achingly gorgeous effects to be wrought with this stuff and sublimities galore, and dizzying pushme-pullyou games of surrogacies and vicarosities to be played, and squinting at the elephant this way lets us get at some of them while dodging the worst of the pejorations: we can speak of food porn, and designer porn, and book porn, and furniture porn, and we all know what it means; we’ve seen it. —Catalogs and lifestyle magazines: some of the most pornographic work we make.

In that sense? Then maybe? This commercial for a pop song skirts that border of the pornographic: a thirst for justice, an appetite for outrage stoked but explicitly, openly left unsated. —Oh but then we see the problem’s not the numbing, not at all: it’s the transference, the metaneed, the outrage pellet, the thing called up and bodied forth only to satisfy something else entirely, something inevitably smaller. The pornography of politics, the smut of Twitter revolutions, the whoredoms of Facebook petitions—

Good Lord. The trouble with the elephant isn’t that it’s hard to describe. It’s that when it gets up a head of steam it tramples everything in its path.

Cockburn, who has made 30 albums and has had countless hits, visited another war zone this week: Afghanistan. And the conflict involves a member of his own family. His brother, Capt. John Cockburn, is a doctor serving with the Canadian Forces at Kandahar Airfield.

[…]

Cockburn drew wild applause when he sang “If I Had a Rocket Launcher,” which prompted the commander of Task Force Kandahar, Gen. Jonathan Vance, to temporarily present him with a rocket launcher.

“I was kind of hoping he would let me keep it. Can you see Canada Customs? I don’t think so,” Cockburn said, laughing.

The vision thing.

So what we have here, this is the discussion forum for Shadow Unit, which is maybe the largest webfiction serial currently available for free out there? I dunno. Certainly has some of the biggest names attached to it, folks like Emma Bull and Elizabeth Bear and Sarah Monette and suchlike. Whichever. —There’s this thread, then, been up for a bit, looking for “second favorite” webfiction joints: fanfic or OG, novels or linked short stories or whatever, but fiction. Prose. Words on a screen. You know? —But after about three responses (including the city, yes, thanks muchly) somebody posts a list of webcomics they like to read, since they don’t really read any other online written word fiction, and that’s it: the rest of the discussion, with one or two exceptions, on this thread devoted to promoting webfiction, merrily and enthusiastically tosses links to webcomics back and forth and back again. (Including the box, yes. Thanks also.) —I mean, there’s reasons, sure. Of course there are. (There always are.) But still. You know?