the Diaghilev de nos jours.

Why must Helen DeWitt always make me weep?

Definitions of distinction.

The novelette is, of course, but a narrower version of the novelatelle, and the novelttine is narrower yet; the novelccine is larger and thicker than the novelatelle, but more of a ribbon; the novelucce is wider than both by far. Noveletti, as a rule, are thin rectangles or squares of plot, while the noveleja is an elongated screw. The novelalde, like the novelccine, is a ribbon, but long, with ruffled edges, and the novelaldine is a novelalde cut into bits. The novelgnette, also called the noveliolini, is short and thick; the novelarelli is fluted; the novel alla chitarra is named for the strumming motion made to slice the theme. Novelozzi are similar to shoelaces; noveloline are ridged, but only on one side of the plot; novelerini are slender and photogenic. The noveloccheri is made without tropes, and so is hard to manipulate; the novelardella is thick and wide, similar to a thick novelccine. The novelagliati is irregular in shape and size, formed from the scraps left on the floor by other novel-shapes.

I am, occasionally, quite mean.

For whatever reason, I’ve been watching old episodes of Alias, a show I never got into when it was running, and while ordinarily I’d be game for anyone who said, hey, let’s mash up La Femme Nikita and Hudson Hawk, maybe see what happens, there’s something so pedestrian about how the show goes about showing how mad the writing seems to think it wants to be—but then the penny dropped: the thing about J.J. Abrams filmmaking (to pull a name from a hat) is how it’s the filmic equivalent of transparent prose: images, that get out of the way of the story—

Pellucid limpidity.

Wesley Osam’s undertaking a series of posts on the Novelization Style, which is a fine-enough name for a thing that thinks it has no name, that imagines because it sounds just like everything else around it can’t be heard, but that once you’ve finally seen it can’t be unseen, like the goddamn arrow in the FedEx logo, poking your eye on every commute, now. —The notion of “transparent” prose, to tug a loose thread, has always so bedeviled me, if only because the sheer folly of seeing one’s chosen medium as an impediment, to be done away with, has always struck me as, well, sheer folly: I’ve whittered on about it before, and it was the subject of perhaps my first-ever twitter rant, but Wesley’s digging in with grace and purpose; go, read. Myself, I just want to take up just a little bit of it, here—

In effect Novelization Style has no narrator—or, at least, the narrator, and the implied author, is neutral, impartial, and devoid of personality. No one is telling this story. It’s a camera, pointed at a set, with no one behind it.

So you don’t ask “Who is the narrator?” which means you also don’t ask questions like “Why is this narrator telling this story? Why did they make these decisions about the plot, or the characters? What do they want me to think about all this, and do I agree?” The story feels less like something someone made, and more like something that just sort of happened. This does not exactly encourage you to think about what you’re reading. When I read a book like Leviathan’s Wake it’s a struggle to actively engage with the book instead of… well, just sort of skim along the surface with it.

This is where the writing gets tricky, because this disengagement is an accidental side effect. But it’s going to sound a bit like I’m accusing writers of writing this way to discourage questions about what they write. This is not even remotely any writer’s goal. I thought I should pause to explicitly note that, to forestall confusion.

Because maybe, if we’re reading something like those old space operas with no place for women, reading thoughtlessly reinforces ideas we’d be better off questioning. A few years ago, because it seemed popular at the time, I gave Brandon Sanderson’s Mistborn trilogy a chance. What I remember is that the pro-democracy, reformist male lead gained some political power and quickly became a dictatorial tinpot general because, gosh, going all Pinochet just worked better. The books seemed barely aware they were making a political argument.

—and set it next to this, from Ethan Robinson’s critique of so much more than The Weave—

A book that raises such specters needs to deal with them; this one does not. In her review of the musical Urinetown Erin Horáková, paraphrasing and expanding on something I once glibly tweeted, analyzes the ways in which a work of art, by presenting a political critique that stops just short of where it needs to, or goes awry at just the right (wrong) moments, can present the appealing appearance of opposition while in effect serving to prop up the system it appears to oppose.

—from which I’ll then move on, to Erin’s critique—

I don’t think the show means to so thoroughly betray its political content and its Brechtian form. It’s not evil; it’s just stupid. In trying to “blow your mind” with this final turn and add another layer of cynicism, Urinetown manages to undo every scrap of work it’s done thus far. Then it has the nerve to sneer that:

Little Sally: I don’t think too many people are going to come see this musical, Officer Lockstock.

Lockstock: Why do you say that, Little Sally? Don’t you think people want to be told that their way of life is unsustainable?It’s rich to say that people won’t hear this story and change, when the musical itself has pretended to be a revolutionary text and then said change is too dangerous, the workings of power too mysterious and wise (however corrupt), and that thus the wisest thing one can do is nothing. This is like that shitty Doctor Who episode “Stolen Earth,” where Davros tells the Tenth Doctor that his problem, as a character, is that he “makes people killers!!” Now that character, at this point in the run, had a score of serious issues, and none of them were that? So the show burns a straw man and tells itself and its audience that it’s gotten to the heart of the matter, that it’s done its repentance. Again, the fail-condition of criticism is reification. In misdefining a problem and/or not offering possible ways to fix a problem while dwelling on that problem in your art, you can just reinforce said problem. Radicalism has issues and is capable of failing itself and those it advocates for, but not quite in the boring, simplistic way depicted herein. Rather than attacking the culture of overweening corporate power and its control over our lives and how that control is redefining our ideas of privacy, the body, etc. (which would be fairly apropos right about now), suddenly Urinetown is talking about vague ideas of personal responsibility, but not in a tangible, useful way. Shit, was the last act written by a Republican?

—and then round it all with this, from Teju Cole:

In McCurry’s portraits, the subject looks directly at the camera, wide-eyed and usually marked by some peculiarity, like pale irises, face paint or a snake around the neck. And when he shoots a wider scene, the result feels like a certain ideal of photography: the rule of thirds, a neat counterpoise of foreground and background and an obvious point of primary interest, placed just so. Here’s an old-timer with a dyed beard. Here’s a doe-eyed child in a head scarf. The pictures are staged or shot to look as if they were. They are astonishingly boring.

Boring, but also extremely popular: McCurry’s photographs adorn calendars and books, and command vertiginous prices at auction. He has more than a million followers on Instagram. This popularity does not come about merely because of the technical finesse of his pictures. The photographs in “India,” all taken in the last 40 years, are popular in part because they evoke an earlier time in Indian history, as well as old ideas of what photographs of Indians should look like, what the accouterments of their lives should be: umbrellas, looms, sewing machines; not laptops, wireless printers, escalators. In a single photograph, taken in Agra in 1983, the Taj Mahal is in the background, a steam train is in the foreground and two men ride in front of the engine, one of them crouched, white-bearded and wearing a white cap, the other in a loosefitting brown uniform and a red turban. The men are real, of course, but they have also been chosen for how well they work as types.

Clear? (—“It strikes me that one of the similarities between great fiction and great marketing copy is the ability to sell the content of whatever it is you’re writing about,” writes RandyC, extolling the importance of transparency in prose, but “Weaker photography delivers a quick message—sweetness, pathos, humor—but fails to do more,” writes Cole. —Which is true not just of photography.)

Wurstfabrik.

So I was setting up to fold the week’s laundry in the living room, and I was looking through the DVDs for something to watch, mostly because the last working Apple remote has gone walkabout, and maybe it’s because the Wachowskis have been in the news lately or maybe it’s because it’s one of the best films of the aughts, a pinnacle of cinematic achievement, but anyway I grabbed Speed Racer.

I mean, the opening sixteen minutes or so alone, a thrilling overture that blithely delivers a payload of unthinkably dense exposition—here is our protagonist, here is his backstory, here his family, his brother who went before him, here’s how the sci-fi cars work, and also all the tricks we’ll be using to tell the story, pay just enough attention to clock our moves, the time-shifts, the colors, the floating talking heads of sports commentators, as-you-know-Bobbing their polyphonic takes on the various narrative threads—it’s a real piece of Gesamtkunstwerk, and you can’t help but feel a little taken aback when the movie downshifts into the first act of its actual, y’know, story (though the disappointment is anticipated, cushioned, soon enough wiped away).

So anyway the story’s unspooling, and I’ve folded a bunch (amazing, the laundry a seven-year-old can run through), and here comes the quiet beat when Ben Burns comes to see Speed Racer in the locker room, after Speed’s DNF’d the Fuji Helexicon, and you realize, damn, they just ran a whole sequence in a conditional tense—anyway, it’s quiet, as I said, and contemplative, we’re at what you might call the hinge between the first act, and the second, which I wouldn’t, but there’s Ben Burns, whom the story’s already told us is our Fisher King, who’d lost his soul by letting them let him win a race, the race, the Grand Prix, only to discover that all he can do after is sit outside the castle, and cast sports—but here he is, come to speak to our protagonist, Speed, and what does he say?

Nice race. Haven’t seen moves like that in a long time.

And, I mean, Speed Racer is technicolorly, obviously a fantasy in any of a number of senses, but I’m speaking strictly Cluthian, for the moment: we see that the world (of racing) has gone wrong; that (its) honorable ideals have been thinned (by corporate corruption, and greed); our protagonist is then recognized (as the racer who can win in spite of it all); and thus the world returns (with all those flashbulbs, and a bottle of cold milk, and a kiss).

So you might think Ben Burns says “Haven’t seen moves like that in a long time” (and not, “Damn, I’ve never seen moves like that before”) because he’s thinking of Speed’s brother, Rex, or of his old rival, Stickleton, or even of himself, and it could be any one of those, or all of them at once, or none, but the real reason why he says that is because Speed must be recognized—and to be recognized, one must’ve been seen before. Maybe not in a long time. But now, again.

(And but one can argue nor would I stop them that the real recognition comes later, at what I’d never refer to as the hinge between acts two, and three, when Speed’s about to storm out of the Racer household in a rage, in an echo of Rex’s storming earlier, much earlier, when Pops sits Speed down to tell him what he didn’t tell Rex, what he wishes he’d told Rex, what might’ve kept Rex from dying, as it were, but sequences can multitask, and I have always read this scene as a fantasy of what a parent might sit down to tell a child who’s somehow, somewhich coming out, a parent who’s come to see how wrongly, maybe, they’d treated a child who came out before, a parent who’s life’s been thinned by the regret of that loss, who’s recognized in the second child a second chance, and oh, the return—)

Anyway. (Did I say that already?) —That, all that, or some approximation of that, was part of what was running through my mind when I got up from where I was sitting, and paused the DVD, and stepped, carefully, over all the folded laundry around and about to the keyboard, and after a moment’s thought, typed this:

We've not seen this in a long time. —fantasy

— Kip Manley (@kiplet) March 13, 2016

We've never seen this before. —sf

We're not gonna see this again. —horror

Madeleine nabobs.

I’m told that professionals, when recording on the road, in a hotel room, away from the studio, will climb into bed and pull a blanket up over themselves, to cut down on ambient noise, I suppose; but I didn’t hear that until after, which is maybe why the audio’s not so great on my end—well, that, and my habit of speakingquiterapidlytillthemomentIsuddenly, uh—

—pause. And the swerve. —But! Jonah Sutton-Morse, proprietor of Cabbages & Kings, invited me over (in part, I believe, based on this old post) to talk about reading, and genre, and reading genre to our kids, and it was a blast: he’s a gracious and a generous host, and he keeps it moving in his finished pieces, and somehow even focussed—despite the material I gave him to work with!

So go, have a listen. —Jonah assembled a slideshow of book covers, a partial list of the titles we discussed, and it skews young, which is to be expected given our focus and purpose, but there’s another skew I wanted to note, here, at least: it’s rather almost entirely pale. —And that’s understandable, I suppose, given our purpose and our focus, and who I was and what I read when I was young, but the very fact I’m saying it’s understandable is telling enough, isn’t it? Or the itch I feel to soothingly point out that it’s a list of things I have read, not a list of recommendations to read, though I don’t not recommend them, or not all of them, anyway, and it is what it was, which is awkward, which it should be, which is useless, which leaves me, what?

(There are moves I could make. Other lists to itemize. But.)

—A footnote, though: one of the last books we talk about was one of the first that ever made an impression on me, in the way that books can, even though I only ever saw a school library copy, and then not ever again for years afterward, forgetting the title, the author, the illustrator, the names of the characters, most of the plot, but not—that thing? Whatever it is, that’s useful to us in a story, when all the rest is worn away? —Once Taran was old enough, I took those bones of a memory and went looking for the book, which it turns out is something the internet’s pretty good at.

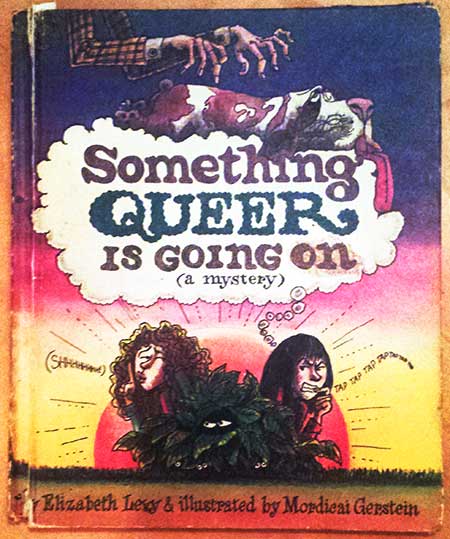

Something Queer is Going On. How (further) disappointed I am in myself, that I might’ve forgotten a title like that! —There was something of a disorienting madeleine-moment, opening the envelope, seeing a lost memory restored and reified with one rather swell foop of that vanilla-ish old-book smell, but more dizzying was opening up those worn boards (the front cover has since fallen off, and been taped) and reading it aloud, feeling the ghosts of the word-memories under what I was hearing my mouth speak, but above all having the two main characters restored: Jill, whose mother is “O.K.”, and Gwen, with her habit of tapping her braces when she’s thinking, and their friendship, which—and there’s nothing that revolutionary about it, it’s not like this was the only or first time it’d ever been done, but still: how shiveringly odd to hold in my hands the first time I’d ever so long ago met the archetypes I’d later lean on, when I started to write about Ysabel, and Jo.

Interpellation.

If publishing a book takes one year, then why do George R.R. Martin’s publishers only need three months? Learn how blockbuster novels can change the book production process.

A standard publisher’s contract gives the publisher the right to conform the text to house style. If this clause is not changed, preservation of the author’s punctuation is a matter of chance—it depends entirely on the discretion of the publisher. If the clause is changed, however, this STILL doesn’t guarantee that the author’s punctuation will be respected.

Once the structural edits are approved by the editor, the manuscript is “accepted” by the publisher and a laser-focused line edit process begins. Line edits are just what they sound like, a line by line editing of an entire manuscript. The editor typically champions this task, keeping the author in the loop in regards to questions or significant changes that the editor wants to make to a line. This can be something as simple as correcting a homophone or deleting a repeated reference (such as Davos clutching his finger bones). Or the edit can be something significant, like changing the tone of dialogue to make a chapter read differently in comparison to the chapters before and after. Sometimes the simple and complex line edits are the same thing, like when a singular word choice abruptly reveals the answer to a series-long mystery. Line edits take a variable amount of time depending on the size and complexity of the manuscript and the series it takes place within, but they typically do not stretch beyond two months.

After line edits, the manuscript is sent out for copy edits. These can be handled by the author’s editor or by a separate editor specifically tasked with copy edits for multiple titles. Copy edits correct lingering grammar and spelling errors, and are focused on technical corrections and continuity rather than content and tone corrections. This process usually does not take more than a month, but is subject to the length of the manuscript and the availability of the copy editor. (Many authors, especially in the fantasy genre, work with a preferred copy editor who is familiar with the world’s terminology and the author’s voice, rather than a copy editor who must learn these from scratch. Having a consistent copy editor for a series also makes continuity errors easier to catch.)

The text was quite complicated, so I offered to meet the copy-editor before she started work. I had made a special trip to New York to try to settle possible difficulties in advance. I had five books that were coming up for completion; I was desperate to get back to them before they were gone; I wanted everything to be as simple and clearcut as possible. My editor called the copy-editor, who said she would rather work through the book first and send me her mark-up. The editor, copy-editor and production manager all assured me that the copy-editor’s comments were only suggestions; I could change anything I didn’t like, and then the book would be sent to the printer. I asked whether there were any points on which the editor felt strongly. If anyone wanted to make a case for some particular point I was happy to discuss it. The editor and copy-editor both said there was no point on which the editor felt strongly; no one wanted to make a case for any particular point. I reminded everyone politely that my contract gave me the last word.

The copy-editor made thousands of gratuitous changes to the book, for which she was, of course, paid an hourly rate. It was then necessary to go through the book thinking about these suggestions—if someone has “corrected” a grammatical mistake, it is always possible that it is a genuine mistake, so one must consult various works on usage to ensure that one has not been wrong all these years. I went through, anyway, marking up the mark-up, and I again made a special trip to New York to make sure there were no problems.

The subsequent line editing and copy editing processes cannot be skipped in the same manner. However, for a title as hotly anticipated as The Winds of Winter, external market forces, a publisher’s annual profit quota, and the intensity of consumer demand for the book would ensure that once a manuscript was completed, George R.R. Martin and his editors would be working on nothing but that book, hour by hour, day by day. So while the intensity of demand wouldn’t necessarily shorten the editing process, it would guarantee an immediate and uninterrupted editing process.

In this office we have a stupid, petty little conversation. The editor explains that if one does not italicise the titles of books it looks like carelessness. He explains that there are rules. The production manager explains that there are rules. I explain that the Chicago Manual of Style has only whatever authority we choose to give it. I explain: Look, these are two characters obsessed with numbers. The Chicago Manual of Style does not have a rule for using numerals in texts about characters obsessed with numbers because THIS BOOK HAD NOT BEEN WRITTEN when they last drew up the Chicago Manual of Style. They could not ANTICIPATE the need for a rule because the book did not then exist. I WROTE THE BOOK so I am obviously in a better position to decide what usage is correct for its characters than a group of people in Chicago who have NEVER SEEN IT.

I say: LOOK, if perceived norms did not exist it would not be possible to mark a text as departing from norms, it is not possible for the texture of a text to be different, to be perceived as original, without marking itself off from norms by departing from them.

What I really needed to focus on was persistence. I’ve worked in the publishing industry and I’ve worked on the floor in book retail before, so I’ve seen marketing from many sides, where it begins, how it’s executed, and how successful it is. And to create an awareness of a new author really takes persistence in all of these areas. A marketing person at a book publisher deals with lots of authors and is probably overworked, so you have to remind them that you’re there, but in a helpful way. Which means updating them on what progress you have made, and suggesting work that you can do to help with their marketing ideas. Your own persistence makes you an ongoing presence to your publisher and the marketing department, which may open up a larger number of venues for you to be presented within. And this all starts way before your book is even out.

They’re looking at me in an embarrassed, pitying way, and it’s kind of funny, because as it happens I am actually a, perhaps even the, world authority on this subject. I really am. The concept of propriety in ancient literary criticism was the subject of my doctoral thesis. It covered ancient criticism, rhetoric and theories of correctness of language from Homer to St Augustine, it took in sociolinguistics, it looked at the subject of linguistic Atticism, it looked at the whole tradition of Shakespearean scholarship with special attention to 18th-century objections to Shakespeare, it looked at the Homeric scholia, it did groundbreaking work on the conceptual difficulties raised by distinguishing propriety (which was seen as stylistic) from purity of language (which for ideological reason was meant to be neutral, a degree zero)—not only was it a monster of erudition, it also brought to bear modern theories of language and literature. The problem is not that I am speaking from a position of ignorance. I am speaking from a position of knowledge to people who don’t know what knowledge would look like. I am talking to people who are afraid that other people who also don’t know what knowledge would look like will read the book and think it is full of mistakes.

What is a good editor like? A good editor offers you decent advances, and goes to bat with his publisher to make sure your book gets promoted, and returns your phone calls, and answers your letters. A good editor does work with his writers on their books. But only if the books need work. A good editor tries to figure out what the writer was trying to do, and helps him or her do it better, rather than trying to change the book into something else entirely. A good editor doesn’t insist, or make changes without permission. Ultimately a writer lives or dies by his words, and he must always have the last word if his work is to retain its integrity.

There’s just one slight problem, which Marx and Bourdieu have thrashed out. A veil of decency separates the search for the ‘best possible book’ from sordid financial considerations. The novel, that bourgeois form of art, has no qualms about poking around in the dirty corners of money and power, but the people who bring these books to the market have a euphemistic discourse all their own, one which makes it possible to talk about money without talking about money. Other forms of art have their own systems of euphemisms, but they are different systems, adapted to the sources of revenue. Bringing the traces of writers’ methods of composition to the market would involve talking in a non-euphemistic way about means of infiltrating those other systems of discourse; people who are euphemising successfuly in one field find that very uncomfortable; it’s unlikely to happen anytime soon.

Market forces also affect the production process of a title. While a novel begins as a work of personal expression by its author, it will eventually be seen by a bookseller as primarily a product. The task of a publisher is to balance the artistic expression of the author with the demands of the marketplace on the product. For a debut author, the publisher and bookseller must work together to generate initial demand for that author and their story. In George R.R. Martin’s case, booksellers want the product as quickly as possible, so a publisher’s task becomes maintaining the integrity of the writing while satisfying the intense demand for the product.

Fighting too long against.

Dragons can be beaten, sure. But the most important thing that fantasy teaches us is there’s this factory, just over the hill, that won’t stop churning out more.

Teleological bees.

So Benjamin Gabriel, Erin Horáková, Ethan Robinson, and Aishwarya Subramanian got together over at Strange Horizons to chat about Jupiter Ascending and if you’re anything like me, you’re not reading this anymore; you’re over there, reading that. —There’s a lot to love in the giddy watch-me-for-the-changes interplay (friends with wing benefits! every young girl a Skydancer commercial!) but I’m going to focus on those teleological bees, or rather the incoherently ateleological, and Aisha’s neatly apt coinage of “world-furnishing” (as decidedly opposed to the clomping foot of world-building), if only because it dovetails nicely enough if you push it with points I’ve made about grit v. grain, and if I don’t leave it at that I’ll just keep babbling on, so.

A bricoleur’s dam’.

Reading the Attebery’s been interesting, and good, most especially the chapters on structure and (most especially) character, but I’m coming up on the last chapter, the one I got into it for, “Recapturing the Modern World for the Imagination,” all so I could start to get at what he had in mind when he coined “indigenous fantasy” which, I mean, well. We’ll see. —I mean, I’ve peeked; of course I peeked: the opening of the second paragraph alone:

Of all the subgenres to emerge within fantasy in recent years, the one that promises to reshape the genre most significantly is as yet unnamed, or rather no name for it has proved adequate.

Written in 1992, five years after I’d already got lost; by 1992, I’d already read Ægypt (The Solitudes, anyway) cover to cover and back again, and oh God Folk of the Air. And since then, but since then, that promise—the promise embodied by this swirling mess of indigenous fantasy (soi disant), this low fantasy, contemporary, postly modernist, magically realist, paranormally romantic, this syncretistic mulch of pulped megatexts, superheroic, supermagical, superscientifictional, these fantasies that “describe settings that seem to be real, familiar, present-day places, except that they contain the magical characters and impossible events of” say it with me now, URBAN FANTASY—what happened? What became of it? Of us? —I mean, we ate the damn world, or what we could find of it, and what good did any of it do?

But in all this, welling up out of all of this, there’s a specific refusal? rejection? repudiation? that I struggle to apprehend, much less articulate, when I turn from this model I’m building to argue with, yell at, kick against, to take up the thing that kicks, that yells, that argues? sermonizes? —There’s an abjunct, between that all-of-this, and the very specific feeling of tuning a sentence just so, of overdubbing detail, of rigging or tripping over structural rhymes, the very peculiar shiver that can obtain with just the simple repetition of a cocked and loaded phrase—map and territory, theory and praxis, forest and trees, I know, I know, but still: I’m either wrong there, or wrong here, and I know where I’d rather not be right.

—Anyway, permit me some links: just about a quarter of the next volume of praxis has appeared since June; I’m hoping the larger cycles have begun to hove into view, and you can see the shape I think it makes, might yet end up making, and that I can keep this discordant bolus soaring, not crashing in a mutter of nothing-or-other:

At the late-night double-feature picture show.

Not only has SF lost some of its power, it has lost its innocence in a world in which the products of science include horrifying war machines and seas of waste. SF has always had both optimistic and pessimistic strains, both A Modern Utopia and The Time Machine, but the difference has been largely a matter of one’s view of human nature, not of the capability and fitness of science itself. Now, however, some writers seem to have lost faith in the scientific imagination, looking outside the scientific megatext for other ways of seeing and judging. Yet there are very few alternative megatexts sufficiently powerful, comprehensive, and familiar to act as a commentary on science. Even religion lacks the authority it once had for many readers, because it cannot match the material payoffs provided by science.

The discourse of fantasy can challenge SF, partly because it pays its own tribute to science. Impossibility itself, one of the elements of fantasy, is defined largely through reference to the current scientific worldview, especially where that coincides with common sense. Because it is the current view of reality that is violated in a fantasy, inventions that were once fantastic may be no longer, or vice versa. The transmutation of metals might serve as an example of both sorts of change: once part of science, then impossible, and now achieved. Nonetheless, we can tell whether the transmutation is to be viewed as possible or not by the discourse that surrounds it. If an alchemist’s description of the philosopher’s stone were inserted verbatim into a modern fantasy, it would cease to testify to the existence of such a miraculous substance and become part of the rhetoric of the unreal. The same description within a science fiction text might be used to represent exploded myth or to highlight the mysterious properties of transuranic metals.

If fantasy were only the denial of science, however, there would be no contest between them. But in affirming impossibility, fantasy opens the door to mythology, which is the name we give to cast-off megatexts. Gods, fairies, ancestor spirits, charms, spells: a whole host of motifs no longer convey belief and yet retain their narrative momentum and—and here is one of the great differences between science fiction and fantasy—their congruence with the ways we wish we saw the world. They are emotionally and psychologically, if not scientifically, valid, and therefore most potent where science fiction is traditionally weakest.

I still rarely put in an appearance in my own sex fantasies. I remember being startled and a bit alarmed when I learned that other people—so-called normal people—did: the person squirming under the hail of blows, or lecturing sternly as their arm rises and falls, is the avatar of the dreamer herself. That seemed to me, when I first heard about it, like only half a fantasy. It still does.

What I love about my two-faced fantasies is that I get to body-surf. Sometimes I’m the spanker, strict and loving, doling out punishment and affection, slowly chivvying my charge back into the world of acceptable behavior. Sometimes I’m the spankee, nervous and filled with dread, embarrassed as I drop my pants and bend over, fighting to remain stoical and then losing the fight, collapsing in tears and remorse.

If I’m by myself or nobody is watching, I might even whisper the dialogue to myself, complete with the appropriate facial expressions (indulgent smile, disapproving frown, quivering lip, tearful grimace).

I keep expecting to outgrow these fantasies and mature into something more appropriate, but I turned sixty last birthday, and the fantasies have stayed about the same, changing only in a 21st century update to the casting (Captain Picard spanking Q, Spike spanking Giles—you get the general idea).

So it should come as no surprise that in my kinky life, I am a switch, someone who enjoys both ends of the paddle or strap or cane. Nor should it be all that startling to learn that my sexual persona is male, and that I expect my partners to treat me as such.

But that’s in the bedroom, or the dungeon. What about at the writing desk?

One imagines that one can escape a category by collapsing it, but if one tries to collapse the category, the roof falls on one’s head. There a person is, then, having not escaped the category, but having only changed its architecture. Once it was a category with a roof, now it is a category in which everyone is buried in the rubble made of what once was a roof over their heads.

Triskele.

Three tangents make a triskele—which is not, you’ll note, a triangle, and thus not nearly so stable as that shape would have it. —Ethan Robinson says:

This goes a long way toward explaining why I love her work so much, I think; often it fixates—again I think the word is accurate—specifically on the question, what makes this work different from any other? what makes it “fantasy” (or, more rarely with her, “science fiction”) rather than otherwise? and answers: one is allowed neither the luxury nor the irresponsibility of taking anything for granted.

When I was very young that sort of thing was frightening because it represented a breakdown of the logic of the world. A worldbuilding incompatibility that cast doubt on the author’s grasp of the narrative, as it were. Eventually I grew up and saw the invisible world as a rhetorical device to avoid ever talking about violence, cruelty, and responsibility, and that didn’t make it any better. That’s just another way that the world breaks down.

And some time ago, John M. Ford went and said:

Fantasy doesn’t make different stories possible, but sometimes it makes different outcomes possible, through the literalization of metaphor that is one of the key things fantasy does. Moral strength can change the real world—and a good thing, too—but in a fantastic story it can make dramatic, transformative, immediate changes. The idea that such transformations always have a price is what keeps fantasy from being morally empty—magic may save time and reduce staff requirements, but it offers no discounts.

Diseffected.

I’m always on the lookout for groups or schools or clubs that might, if they knew of me, have me as a member, so that I might Marxily walk away before they think to ask; so when the Millions teased the heralding of a New Modernist age (with a parenthetical invocation of Josipovici), well—I had to go take a peek.

More recently—say, in the last 20 years or so—numerous so-called postmodern novels have contained this distinctly non-postmodern quality—not that the characters feel so much as the reader. The cumulative effect isn’t necessarily a fully fleshed-out character but a fully emotional experience. Think of Jonathan Safran Foer’s strong sentiments in the face of the Holocaust and 9/11; think of the alligator-wrestling family at the heart of Karen Russell’s Swamplandia!; think of the way Ali Smith works her linguistic magic in order to convey the complexities of love and relationships; or the heart-breaking wallop of David Levithan’s The Lover’s Dictionary; think of Reif Larsen’s I am Radar, of Zadie Smith’s NW, of Téa Obreht’s The Tiger’s Wife. Can these books truly be considered postmodern when the most prevalent aspect is emotion rather than thought?

Consider the way even genre fiction has been infiltrated by humanity and feeling. Science fiction is no longer merely speculative, adventurous and pure fabulism. Now we have Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, and myriad others. Fantasy is no longer characterized simply by lengthily described worlds and political intrigue; now we have Karen Thompson Walker’s The Age of Miracles and almost everything David Mitchell has written. These so-called genre books now aspire to human heights.

So, well, yes—careful with that cricket bat, Eugene—not so much of a there there. —I drew what amusement I might from the idea of a return to modernism’s warm emotional core, a repudiation of the chilly formal games of postmodernism, but it’s weak tea at best, and then there’s the evocation of Franzen. (Turns out postmodern tropes are like thermal curtains: not as embarrassing as one first thought.) —I mean, I did then pick up the Attebery I’m leafing through, for reasons, turned the page, and laughed at the juxtaposition of the previous with this paragraph—

John Barth has described the reductio ad absurdum of the Modernist movement in his essay “The Literature of Exhaustion”: “Somebody-or-other’s unbound, unpaginated, randomly assembled novel in a box.” According to Barth, Modernism’s program of “disjunction, simultaneity, irrationalism, anti-illusionism, self-reflexiveness, medium-as-message, political olympianism, and a moral pluralism approaching moral entropy” was accomplished by the middle of this [past] century. Readers had been educated, had grown wary of literary illusion, could no longer take narrative or narrator for granted. Nothing remained for Modernist writers to exercise their irony upon, and so Modernist fiction had nothing more to say.

—but that smacks entirely too much of pulling Marshall McLuhan out from behind a fern, and anyway, a page earlier Attebery was summing up Edmund Wilson’s take on modernism as “essentially mimetic reporting striving to turn into lyric poetry,” and would you look at that? I’ve been a modernist all this time.

I suppose I shouldn’t be too unkind—charity, and resounding gongs, if nothing else. It’s understandable that modernism and postmodernism are so easily confused: postmodernism’s merely what modernism gets up to in our bedroom after the war, and you know me: I’m a partisan of that small country, mindful of death, disinclined to long journeys, ever since the war and all, you know. —Which may not explain to you why I eagerly clicked on the link to an article titled, “For the future struggle: what is science fiction?” but trust me, I was eager to read something with a tagline that read, “The science fiction that is most important is that which situates itself at a point of struggle.” (—I want to be wrong. —Doesn’t everyone?)

I was eager, but I read it with a deepening frown, a weightening sigh. It isn’t so much a paean or a how-to or even a why-we-must on revolutionary SF; it’s just a minor jeremiad against utopia, which, I mean—

The originating Utopia of Thomas Moore’s 16th century novel was founded by King Utopos, who cut off the peninsula from the mainland, making it into an island. Utopias are, like their primary ancestor, closed systems, functioning perfectly without class, oppression or struggle. As islands, cauterized from the world, proper utopias are resided in by unchanging, eternal societies, a conception which is both absurd and bordering on fascism in its undemocratic and unquestioning existence.

Utopias then are in fact antithetical to science fiction. They are more like a blueprint of a future society, instructions and pictures of a post-revolutionary world rather than stories set in those worlds. Narrative relies on change, process and struggle, all things that cannot happen within a utopia in which struggle, need and desire have been banished.

—sure, if you define it like that. —Utopia is when our lives matter, dammit, and if you can’t make that storyable, God help you. —Inept utopias are bad, to be sure, but these future worlds the mode demands as backdrops for its narratives and struggles—when the action pauses for a moment, and you take a breath, and look around, and see just how it’s different, the then and there, from the here and now, that such difference is imaginable, possible, that it’s amazing, frightening, thought-sparking, utterly uncanny, the home you never knew you could have—this is what breaks hearts, cracks heads, keeps Plato up at night. (It’s also what can bring on the abjunct, yes. I mean, I know I’m wrong. It’s impossible. Look around you.)

So maybe we wouldn’t disagree, Stupart and Dillon and me, ends and means, broadly speaking and all that, it’s just how we marshal our arguments, but still, details matter, I mean theirs or to again be charitable the constraint of wordcounts or something leads to a tendentious misreading of Delany’s Triton: Some Informal Remarks toward the Modular Calculus, Part One—

On this heterotopia on Neptune’s moon, Triton, the lead character Bron attempts to live in a post capitalist world where anyone can change gender and sexuality at will and structural oppression appears to no longer exist. However, despite living in a world ruled by individual freedoms, religious mania, the threat of war and violent subjectivities still exist, as typified in the main character themself.

—by way of demonstrating that Triton is one of the good ones, the not-a-utopias, see? Struggle! —But Triton is a utopia, where all our stupid petty bullshit misunderstood and -standing lives matter. —The war, the very real and not at all threatened war, comes from outside Triton, from way back down on Old damned Earth, and maybe I cling to this because these days when I think of the book it isn’t Bron’s shaggy-dog of a story that sticks, or the New York City I can see in it now that I’ve lived there (once, and long ago), or even the game of vlet; what looms over everything else in the book now comes at the very end, Appendix B: Ashima Slade and the Harbin-Y Lectures: Some Informal Remarks toward the Modular Calculus, Part Two, the part that begins:

Just over a year ago, at Lux on Iapetus, five million people died. To single out one death among that five million as more tragic than another would be monumental presumption.

One of the many, many to die, when gravity and atmosphere were stripped away from the city by Earth Intelligence sabotage, was the philosopher and mathematician Ashima Slade.

And, I mean—

Falling will fall, fell.

The Fall, okay, but did anything ever actually fall? Did the story ever scale vertiginous, dizzying heights, only then to plunge? Or the characters, or a character? An action? —Not as such, no. —Mostly I’m left with a lingering confusion with Tarsem Singh’s spectacular 2006 film whenever I try to talk about it, which is annoying, but mostly to me. —Oh, this: I wrote this a few months back, as part of a conversation with Lili Loofbourow about why I’d liked it, and she hadn’t, and why I’d ended up coming rather forcefully around to her side of the matter; she’s the “you” in what’s below, and this piece in particular is what it’s responding to—treat this post, if you like, as an off-brand badly xeroxed fanfic installment of Dear Television, or something, with parenthetical interruptions from the show itself as it was being written about. —Anyway; enough prologue: with the announcement of season three, and with the occasional bits of praise I’ve been seeing from others (who really ought to know better), here’s the matter as it began the beguine back when:

The Fall, okay, but nothing ever fell, as it were. Except, y’know, the bad guy, I guess, at the end? —And oh for God’s sake Milton? —I’m typing this as the last episode is playing on the other screen, so there’s another piece of evidence to add to the snack-grabbing and beard-shaving you noted.

But first maybe why I liked it, or was liking it, or was thinking it was something I was liking. (Gibson’s one technique is to play on, or instruct others to play on, the desires of her subjects, and welp, here’s Spector looking right at the camera in the interview room and calling our attention to precisely how clever this is.) —Sorry. —The first season was appointment television for us, in the sense that Jenn and I made appointments to sit down and watch an episode or two together, when we got a chance, between day jobs, childcare, and creative enterprises. (And now Gibson’s proxy with Katie, the handsome young detective she requested before she knew she’d need a handsome young detective, has just made a mess of getting any actual information from Katie, and made a hash of treating Katie in any sort of a humane fashion, but has of these two mistakes made what was supposed to be a dramatically satisfying moment.) —Other appointments were made for Hannibal, and Top of the Lake, and (in theory) The Good Wife, and Orange is the New Black, but: appointments are hard to keep, and it’s easy to watch television while you’re doing something else, like coloring comics, or running maintenance routines on a database, which is why she’s watched all of Orange herself, and I’m caught up on Good Wife, and we never did finish Top of the Lake, which I’m tempted to go and take up again now, and feel a little guilty about that.

(The mannequin in the trunk. I admit I’ve completely lost track of where that was supposed to’ve come from.)

But! The Fall! Gillian Anderson rocking her cool, severe British accent! Rainy grey cinematography! (Oh, and here’s the daughter’s interview, to remind me where that damn mannequin came from, though damned if I can actually remember it myself. And Gibson, tearing up, telling her proxy precisely why she’s tearing up, thanks.) —What’s not to like, really. (Oh for God’s sake the miscarriage.) —Sorry. That first season of The Fall we did finish, is the basic point, I guess, and there’s a there there: the aforementioned, plus a slow, steady, controlling hand in the direction, a keen eye for place, and a fascination with the minutiae of process—as opposed to the sterile gestures of the procedural, which I should mention as another media-consumption data point: the fucking procedural, the Castle and the Bones and the House and the Elementary and the Person of Interest and the Psych and the Leverage and yes also the Miss Fisher’s and that dam’ Good Wife, each with its rhythms, its shorthands, its conventions, and though they may play with them, some better or at least with more evident joy than others, or mutate them over the course of their run or even once or twice upend them utterly, they’re still there, implacable skeletons that mean you can queue one up on the one window of your computer set-up and go about your business in the other and surface three or four hours later having watched four or five episodes without ever really seeing one, you know? —So when there’s a show that doesn’t immediately tip its hand, that takes its time, that buries the lede, I suppose, I tend to sit up and take notice, but also to cut it some slack.

(And here we are, the confrontation we’ve been slow-burning our way to through ten previous episodes: Gibson v. Spector, cara a cara! —I paused the playback to put some additional fillips on clauses, here and there.)

One of the procedurals I was watching in and around the same time was Criminal Minds, which, ick. —I watched some of it in small part because of Mandy Patinkin, but mostly because there’s a webserial by a group of genre writers, some of whom I’ve been a fan of since high school, such as Emma Bull and Steven Brust and the infamous Will Shetterly, who was once more firmly on the rails (“It is utterly compelling, compulsive,” is not the language of someone speaking about a thing they’ve experienced themselves, but of someone attempting to describe what they’ve seen someone else experience, which—oh, never mind)—Criminal Minds, yes. The webserial’s a game of procedurals—it’s called Shadow Unit; the authors take turns writing short stories which are (sort of) thought of as episodes of a television show, sort of horror, sort of urban fantastic, about a semi-occult task force in the FBI—I had something of a professional interest, as well as enjoying the stories, and seeing what the writers were getting up to with something of a new-media experiment. —Anyway: they’d talk about enjoying this program, Criminal Minds, which they’d based Shadow Unit on, so I finally got around to watching some episodes, and wanted to take a long hot shower after: Bones is full of deeply unpleasant, self-absorbed people, and Castle’s awfully blasé about death and civil rights violations, and House is just plain mean, but Criminal Minds is the foulest moral pornography, a terrifically ugly example of reveling in what you pretend to condemn, ideology they don’t even bother to rinse off much less gussy up, which is why, I’m sure, it’s on its tenth season or whatever over on CBS.

I mention (all) this because what was compelling, what was compulsive about the first season of The Fall, for me, was how it handled Spector. Unlike a procedural’s monsters-of-the-week, he’s very much a part of the world: he has a job, he has appointments, he has a family, and a family has him, and this humanized him—in a very frail, limiting, deflating way, deftly making the point that Gibson rather stentoriously makes to Burns just before this climactic interview: he’s just a man, a person, a human being. No monster, not in any sense of the word. Not empowered; not invincible. Arrested.

The attention paid to the logistics of his activities, the lack of attention that seemed to be shown for any attempts at patly explaining or reasoning through the why of what he was doing—it’s not, of course, that this has never been done before, but it was such a welcome change of pace from the Criminal Minds approach that, well, I mean. If you’re going to watch shows about serial murders and rapes and such.

And none of this is to take away from Gillian Anderson and her Gibson, about whom so much ink has been spilled—though dear Lord, to insist she doesn’t pursue self-destructive sexual relationships? Every single one we see either risks or damaged, long ago, some aspect of her professional life, which is the only life we see. —But I digress. I was talking about Dornan’s blithely pathetic Spector.

(“The people who like to read and watch programs about people like you,” says Gibson, and fuck you, show; you just blew the last of my good will right out the window with that direct punch on the nose.)

—There’s two moments, in the first season, that jolted like electric shocks, and fixed it in the plus column for me. —There once were, I should say. —The first was when Spector crept into his sleeping daughter’s bedroom, climbed up on her bed, pushed away the bit of ceiling and tucked his book away in the attic: brute force, perhaps, but still: the mean logistics of his evil, how it had to be folded into and worked around the quotidian, how—and I’m gonna digress for a moment, but: I did a lot of babysitting, in high school? And one thing I discovered, after making sure the kids were asleep, when I went snooping about the houses, as one does when one babysits, one thing I discovered was almost every single house had a stash of pornography, and sometimes it was under the bed, and sometimes it was in a nightstand, and quite often it was on a shelf high up in the closet; anyway. This little depth charge of someone else’s desires, squirreled away. —The moment had resonance. There was a shivery horror to it that stuck.

The second moment was that first phone call between Spector and Gibson. It’s the first time he gets to perform as the monster he’s supposed to be; it’s the first time we’re privy to any attempt to explain why he does what he does, and, well, as with any of these shows or stories, it’s bullshit, utter adolescent cod-Nietzsche bullshit. But: the show knows it’s bullshit. And astonishingly, electrifyingly, for that one moment Spector gets to know it’s bullshit. He falters, he hesitates, there’s a look in his eye—that feeling, when you’ve been living with an idea, holding it in your head, telling it to yourself, and you finally get a chance to say it out loud to someone, and you hear yourself, the words coming out of your mouth, and you realize it’s all crap, the magic’s gone, it was never really there in the first place—to have that basic interaction applied to serial-killer nonsense was beyond refreshing. It felt revelatory. The weirdly anticlimactic structure of the first season, with no actual confrontation as such, with him getting away, as it seemed—it felt deliberate, as if the show wanted to say forget catharsis, forget quote-justice-unquote, this, here, this moment, this is the important thing to take away: he’s pathetic, he’s feeble, he’s destroyed real people and that makes him contemptible, he’s just a person himself, and there’s no deep insight into rage or fantasy or desire here. Go home.

So, y’know. I liked it.

(And yes, of course, Rose is alive! God, what a weirdly desultory bit of plot that was. I will say that a show that has become this fetishistic about process and detail is nonetheless and of course terribly squeamish about what and how a person might excrete, trapped in a trunk for was it three episodes? Or four?)

There were a number of ways the show could’ve carried on into a second season; what I’d thought—Stella Gibson moves on to another

(—oh for FUCK’s sake extrajudicial execution ex machina—)

where was I? —How it could’ve carried on, yes. The continuing adventures of Stella Gibson as she moves on to another town where she’s had an inappropriate relationship with someone in the police hierarchy that might compromise yet another investigation of a sadly all-too-human fuck-up drunk on patriarchal power, haunted every now and then by the one that got away, in Belfast—that wasn’t going to happen. Spector retreating, doubling down on his bullshit in isolation, resurfacing to try and make another go of it, okay, there’s possibilities there, and the fact that he does find someone he can articulate his bullshit to, who’ll validate it and egg it on, and it’s a teenager, there’s potential there, too, dicey, but. (Oh, Katie! I really hope you end up in a Kelly Link short, so you can finally become the whacked-out Nancy Drew you so desperately want to be.) —Anyway. Second season, I was still on Team “Aw, I liked it” through the first episode and into the second. I’m a sucker for brooding on ferries, what can I say.

But! That third episode. Two moments, again: first, there was the dizzying bewilderment that came when, almost immediately after Gibson gives a distraught-for-her tirade about how it’s the task force’s fault that Rose was taken by Spector, Archie Panjabi’s M.E. (I nip over to another tab to Google—her name was Reed Smith? What?) rather firmly informs Gibson that it’s highly likely Spector found Rose because of the task force, and Gibson nods, considering, yes, this is likely true. It was like two scenes from two alternate takes on the story slapped into the same show without anyone realizing the causality breach, and while I’m as big a fan of kicking over the traces of story-logic as the next fellow, they don’t need to be so carelessly Brechtian. —So that was the first moment I sat up and said, wait, show, what?

The second comes at the end of the interminable sequence in Gibson’s hotel room, after the bit in the bar, and the wildly, desperately obvious fanservice-kiss and flirtation. —We get Spector’s infiltration of the hotel, which is insultingly contrived: the waiter’s just put down a tray right by the service entrance! He’s left a master key-card on the tray! Spector knows what a master key-card looks like, and can do! Look, room-service orders, hanging on the wall right there! And that one, right there, it’s from Stella Gibson! See, how cleverly he hacks the script? I mean, the hotel? —And all of it done in one shot, too. I’d‘ve found it far more “realistic,” far less noticeable and off-putting, if the show had just made it clear he’d broken into her room somehow, who cares, let’s not bend over backwards to justify how. —So there’s that. There’s Burns, dropping by to whinge drunkenly about the B-plot of the first season, and since there’s no further fallout from this the only reason he does so is to get punched, which, okay, good moment there, and then he gets cleaned up, and more discussion of this or that explicative point, and then we shifted somewhere else I think? Long enough for Stella to change out of her suit into a robe just like the one she was wearing in the dream sequence, huh, and then she boots up her computer to see what Spector’s done to her desktop, and—she leaps for her gun!

Which is an impulse I can totally understand, if one were used to guns, and had one at one’s disposal. But in the flow of the episode, the tonal shifts, the way everything intervening had been strung out to such lengths, how we’d already had the one confrontation in that hotel room just minutes before, it felt wildly out of place. I laughed, when I should’ve jumped. A definite stumble.

And then things start to snowball, and where I might’ve cut some slack before, I now shook my head. Spector’s wrestling with logistics becomes instead superhumanly smooth urban-ranger skillz, to the extent that he seemed to be colluding with the writers to get away with stuff. The minutiæ of process becomes fetishistic, calling attention to precisely how much labor and money was being poured into this task force that can’t seize actual evidence from a house they’re destroying to surveil. (Though I did initially like the murmuring Greek chorus effect of the surveillors all checking in with dispatch, it got numbingly repetitive after a bit.) —You mentioned the slow-motion shots of his being hauled into the police station; I found the sullen gotcha! of his arrest to be, well, arresting: let him go from the scene of the officer-involved shooting, as if he’s not a person of interest in any other matter, let him walk half a block away, look about, and then let someone else march up out of nowhere to arrest him for Rose’s abduction—why? What on earth was the point of that?

I’d like to think the show itself was aware, just for a moment, of just how far it had fallen when the abusive husband got the phone call from his mate, oh, hey, I just saw your wife, the one you’ve been looking for. —But I can’t be certain.

Looking however briefly into the production history it’s easy to take what I think I know of the making of these things and run some diagnostics: the first five shows were ordered in one batch, and proved so popular a second batch were ordered, and not everyone could come back for them, including the director of the first batch, so the writer directed the second run, and voila! And now there’s going to be a third. —But this reading is awfully generous to my own half-considered initial impressions of the show, a decent-enough first outing run into the ground by a thoughtlessly extended second, so I distrust it, because what the hell do I know. —I’m left with a point Sady Doyle made about Agent Carter, about how feminism is just a button to be pushed now by multinational corporations, a niche to be pandered to, and that’s kind of what this feels like: hey, that misandry’s pretty popular with some folks, let’s see if we can make a splash. —But that’s uncharitable, and I do try to have some charity, so I’ll walk that back; it’s not worth it as a punchline.

So. Anyway. —Thoughts! I had some.

That's no moon.

“And maybe this was useful for Moonie. Maybe it was therapeutic for all of us, to sit with our problems in a tauntaun-adjacent space. It was hard, though, not to feel that something had gone awry with the basic promise of imaginative escapism. No one’s fantasy of Star Wars ever involved hearing a depressed fiftysomething complain about his stepson, or eavesdropping on herds of leetspeak-bros debating the pluses of different skill trees. But that was the world Star Wars Galaxies gave you. It implied two lessons, neither unique to fantasy fandom but both still useful when thinking about it in 2015. Nothing ruins tourist destinations like tourists. And you can run to Dantooine, but your wife is still going to smell the cigarette smoke.” —Brian Phillips

Done did read.

I figured it out on the way there, the intro, which I had to mostly scrap because when I timed out what I was going to read it took eight minutes when I’d thought it was only going to be five and we only had ten, each. But if I just jumped right into it, which I did, when I first moved to Portland, twenty years ago, the first article I read in the Sunday Oregonian was a Randy Gragg column about the Moonday T-Hows, does anyone remember the Moonday T-Hows? And it’s a young crowd, so I don’t have much hope, though it is a ’zine crowd, so maybe, and there, at the back, a nod, a yes, okay. —This amazing space, built out of scrap lumber and windfall and like eighty-five dollars’ worth of supplies [ed. note: it was $65] that hosted parties and get-togethers and just hanging out being in a place stuff, community stuff, that came together and tore itself apart all in one summer and was gone before I even got here. It, seized my imagination, and when I started to write City of Roses, it couldn’t help but work its way into a story about magic in Portland, this fantasy—

And I’d like to blame it on a certain blogospheric kerfluffle, I would, the deprecating shove I gave that word, “fantasy,” the irony with which I larded it, but that would be wholly unfair; I would’ve done it anyway. It’s a ’zine crowd, and of all the worlds I flit about, gadfly-fashion, comics and genre, fandom and criticism, politics and self-publishing, it’s the ’zinesters where I feel the least at home? —For all that I, y’know, make ’zines, pretty much the only necessary and sufficient condition for being considered as such—certainly far more than I do comics or fandom or criticism or anything else. —Oh but there’s more to it than that; there’s all the myriad unspoken ways and means, and beyond the staples and the xeroxing, well. —I always feel off-kilter, doggedly serious where light-fingered irony is called for; digging for sarcasm when the mood’s gone earnest, and off-kilter makes me defensive. I lard. I shove.

—this fantasy, I said—

And the thing was, this was the transition in the introduction, shifting deftly from the personal history of the thing to how it’s situated in the story, the excerpt I was going to read, which is about Luke, and Jessie, and the ghost of a memory of a teahouse, but leaning on that word, defending what it might leave open, betraying it to reach out to the audience, hey, we both know what’s what, right?

This would be why preparation and ritual are essential to any proper working, and also why you don’t whip up a bit of untested oratory half an hour before you go on.

—I botched the transition, is the thing. Got tangled up in Luke and Lake, Thursdays and Mondays, continuity hobgoblins, what-happened-last-week-on, losing the feel of it in the handful of all the facts, and tripping over my feet, as it were, in my haste to get on with it. —The reading itself went well enough; it’s got some swing to it, the excerpt I read, builds a head of steam under an adolescent tantrum, and I do all right with something like that. But I’d lost them, with the shove, and the stumble. The applause was polite.

Reading into.

Well it’s been a while since that sort of thing went on.

And as usual during the writing it got to the point that anything I meanwhile read could’ve been folded in, and I honestly couldn’t say whether you ought to then mistrust the writing that I do, or the reading? —Like as a for instance this piece by Anna Zett on Jurassic World (and what is it with the ice-cold takes on this godawful sequel, damn) which keeps sending up offhanded flares that briefly, brightly, coldly light up just how many and how big, the consequences that depend from the central image-premise, the dragon-like dinosaur-sylph, their skeletons the remnants of an age before a history-ending time-splitting world storm of extinction, and O the FANTASY of using SCIENCE to conjure them once more, spiced with a dash of HORROR at our hubris, thinking we could bring back something so long lost, and all because we wanted, we wanted to justify, we wanted to punish ourselves for wanting just one shivering glimpse—

—but that, that’s the first film, and we’re on, what, the fourth iteration?

There is only one thing that is new in Jurassic World: it is the lack of references to paleontology or what they call prehistory—in fact to any history from before the 1990s. Whatever happened before the supposed “end of history,” before digitization, before the creation of the brand, does not matter anymore. These dinosaurs are no longer creatures of a prehistoric time. They have changed their genealogy, become 250 million years younger and entirely virtual. Therefore they look exactly like they did in 1993, despite the fact that in the meantime the look of many dinosaurs has changed significantly. According to recent research, now mostly based on dinosaurs found in China, these bird-like animals may have had bright feathers and multicolored skin. But feathered raptors and colorful T-Rexes are missing from the American theme park of the present. The filmmakers decided to just stick to the brand. So despite the ubiquity of up-to-date smartphones and smart watches, despite its slick corporate aesthetics, Jurassic World is a spectacle of nostalgia.

The goal has become to conjure a(nother) dinosaur—not to reach for that desire, doubt, belief by conjuring a dinosaur. —And oh but this is such a jejune, an anodyne reading—instead, instead: you remember when Kristen McQueary wrote that column which will forever hang about her neck, about how she wants Chicago to have a Katrina of its own, a world storm that might (okay, figuratively) wash away the old bad union-haunted world and usher in a shining post-apocalypse of neoliberal ahistory? (McQueary has since nopologized.) —Anyway, while that was raging, I ended up reading this profile by Carrie Schedler of chef and restauranteur Iliana Regan, Queen of Midwestern Cuisine—

In the woods, Regan sees a lot of things people miss—and what she sees has become the basis for one of the most distinctive restaurants in the city, a scrappy tasting-menu-only spot in an unmarked storefront on Western Avenue, sandwiched between a soccer store and a tire shop. The 35-year-old opened Elizabeth in 2012, and in her first gig as head chef, she has garnered (and maintained) a Michelin star and been named a semifinalist for a James Beard Award for best chef in the Great Lakes region. The first round of tickets for her last menu, a foraged riff on the foods of the Game of Thrones books, sold out in two hours. “What she’s doing is completely unique,” says one of Chicago’s most celebrated chefs, Schwa owner Michael Carlson. “She’s clever, smart. Totally innovative.”

Elizabeth often draws comparisons to Noma, the restaurant in Copenhagen headed by René Redzepi and considered one of the world’s best, in part because of how it revels in the not particularly celebrated bounties of the Nordic countryside. Regan does the same with the bounty of northwest Indiana. And in doing so, she has accomplished the unthinkable: She’s taken the food of the Midwest and made it sexy.

And, I mean, yes, but, there’s a lot in here for me to like, to find her likable, this Regan, quiet, bookish, inked and buzz-cut, speaking in paragraphs, sharp dry wit and ready smile, but mostly her cantankerous persnicketiness, her inability to sum up, her indisputable drive, that’s found such a constructive outlet, recreating and reinventing flavors from her family, and I’d try a piece of that smoked watermelon, hell yes. But; but—

Prepping for this summer’s menu—an exploration of the foods of the American Indians who lived in the Great Lakes region in the 18th and 19th centuries—was a months-long labor of love. Spare moments were spent poring over articles about the eating habits of the Ojibwa tribe and scouring cookbooks for tips on how to make pemmican, an energy-bar-like blend of meat, fat, and fruit consumed by the native people of North America. Diners can choose from two categories: the meat-heavy Hunter or the vegetable-focused Gatherer. Edible ants will make an appearance. “I’m approaching it from a scholarly standpoint,” Regan says.

The world storm’s long since gone, here, but its effects are everywhere you look, in how it is she’s come to find herself in Northern Indiana, summoning up authentic local flavors rooted away off in Scandinavia and Eastern Europe, in how she’s left to scour a scholarly apparatus of cookbooks for hints of the food that was eaten by people who yet live all about the Great Lakes—though mostly further north now, granted, up in Michigan, and Canada. —There’s nothing of the sylph about food; it’s either there, on the plate, or not—but flavor’s the very essence of a sylph, half-made or more as it is of the stories we tell about where it came from, what was done to it, who figured that out, and when, and how it’s best eaten when served up before us, and this fantasy of reaching back to half-understood notions of the food of an utterly other, othered world—but all these conclusions I’m drawing, from a single paragraph written by someone as tangentially involved as any journalist. —And I’d have to admit to some curiosity, on my part? —Certainly more than for a Game of Thrones menu, say.

Oh but maybe this old appreciation of Kate Bush that I tripped over on Twitter?

Although [Wilhelm] Reich’s writings found favour in more occult circles, mysticism and hippy platitudes get short shrift in Bush’s songs. Images of trees, mountains, skies and waves—romantic clichés on the surface—are militantly material. For both her and Reich, nature in all its chaos and danger is the energy required to be fully human, from the kick inside to Aboriginal “dreamtime.” This theme has been explored since “Them Heavy People,” her 1978 tribute to Gurdjieff and whirling dervishes. As with the momentum of so many of her songs, the modern subject tends to retreat from this energy under the fragile armor of contrived personæ (“Wow,” “Babooshka”) or technological hubris (“Breathing,” “Experiment IV”). Since the industrial revolution, unmetered energy has been treated like some ineffectual ghost, yet her lyrics often read like open invitations to it. The Red Shoes alludes to the dangers of unleashing dormant ecstasy as much as Wuthering Heights. However they may be the kind of energies that don’t need to be harnessed so much as embraced, the knowledge that is “sat there in your lap”—

—and I was going to I don’t know get excited about that move there being a way through and out the recognition and return of Clute’s idea of fantasy, for the here-and-now, the reading-into impulse gibbering full-speed behind my wide unblinking eyes, that to be human is to be destroyed by extremes, of Light, of Dark, of that very energy, so it’s only human to turn away, “modern subject” or no, and remember what John Henry Tyler said, about how it is we’re all connected, so we’re all contaminated, every last one of us is tainted, purity is the last thing we can stand, but Christ, why was he pointing a gun at her? What the hell was that about? —But then I remembered it’s essentially the endgame of any nominally mimetic text that dips a toe in the shallow end of the numinous—recognize, return, retreat, refuse, restore. —I can be quite slow, sometimes.

(A train of thought is not unlike a story, in that so much depends on where you manage to stop.)

I could point back to this possibly alternate take on the Triskelion, as I’ve been noting it, our paranoia positing (and fomenting) actual and imagined dynamos, frantically striving for some sort of order; the idylls our dreams, those high-water marks we can see with the right kind of eyes, both the aims of and threatened by the dynamos; the decoherence event lying necessarily in wait, to tumble whatever houses of cards either might toss up, almost by accident—or maybe just admit, here and now, between ourselves, that these Great Weird (Boy?) Theories are just the work of idle hands at dynamos, inimical to idylls, and, I dunno. Go do the work, instead of pretending to have thought about the work yet to be done?

So, go. Read this instead.