Existing in grids and swerves.

You know that London swings.

New York’s a grid.

Chicago swings.

Just about every writer who’s tried their hand at a comicbook script has when describing a scene or a panel to be drawn said something like ZOOM IN or TRACKING SHOT or SMASH CUT. The artist, when they get the script, will roll their eyes heavenward in a silent prayer of not again, before taking up their pen to attempt, once more, to suggest the dynamic motion of cinema with the one-fixed-image-after-another of comics.

(Fun fact: that writer and that artist can easily be the same person.)

It’s jargon creep, is what it is. —“Jargon,” we are told, “is the inevitable outcome of the specialised communicational needs of professionals, who require terms for things and situations which they, as a matter of necessity, have to deal with every day of their lives, but which do not enter into the world of the man on the Clapham omnibus except as occasional ‘technical’ matters,” and that’s all well and good insofar as it goes, but when one’s specialised communicational needs are themselves relatively abstruse, expressed in terms of art only haphazardly taught or even studied, with critical apparati that have only just begun to assemble themselves, well: it’s only natural, to reach for something closer to hand, superficially similar (bright colors! pretty pictures! explosions!) but colossally more popular, more easily reached from the Clapham omnibus, and thus more familiar, more well-known—superficially, at least: an approximation of the tools it’s built to satisfy its own specialised communicational needs, osmotically assimilated from backstage tell-alls and glandhanding chroniclers eager to demonstrate an almost professional grasp of the technicalities, and voila: a tracking shot that zooms in to a smash cut. In comics.

—Which isn’t to say there’s never a point in trying to evoke in pen and ink the cinematic swoop of the one, the celluloid abruption of the other, or that interesting effects couldn’t be gleaned from the attempt, but you need to think about how to do that in comics, and what that will do to your comic, and whether the effect is right for the moment, the scene, the story, and reaching just for the closest jargon to hand isn’t doing that thinking. At best, it’s offloading that thinking to our weary, prayerful artist (see above). —Nor is this some sort of Hulked-out Sapir Whorffery, where because you’ve turned to the jargon of cinema, you can’t think in comics at all; but. But: the trick of unthinkingly reaching for metaphorized jargon is that you just don’t bother to think it. You think you already have.

It is possibly the predominant narrative mode in Western movies, television, comic books, what-have-you. And now I learn (via Warren Ellis (via Gene Ha (who cribs it from Dennis O’Neil who deems it “the best imitation of life possible in a work of fiction”)))—it has a name: The Levitz Paradigm.

Speaking of which. —The Levitz Paradigm (also known as the Levitz Grid, which it isn’t) is not a narrative mode, much less the predominant one of anything West of anywhere, and while it’s a useful tool for (a not inconsiderate number of) television shows and (quite a lot, really, though less than before, of Yankee-style) comicbooks, it’s got nothing at all to do with movies as they are currently practiced and produced, to say nothing of novels, and as for your what-have-you, well. And Denny O’Neill’s remark must be approached in a context of specialised communicational needs that straiten severely the very meanings of “best” and “imitation” and “life” and “possible” and “work of fiction” to make the sense it does: “Basically, the procedure is this,” he tells us:

The writer has two, three, or even four plots going at once. The main plot—call it Plot A—occupies most of the pages and the characters’ energies. The secondary plot—Plot B—functions as a subplot. Plot C and Plot D, if any, are given minimum space and attention—a few panels. As Plot A concludes, Plot B is “promoted”; it becomes Plot A, and Plot C becomes Plot B, and so forth. Thus, there is a constant upward plot progression; each plot develops in interest and complexity as the year’s issues appear.

That’s it: the Levitz Paradigm.

The Levitz Grid (which isn’t a grid) is likewise simple enough: jot your issue numbers or chapter titles or whatever designation you might have in mind for your buckets-of-story along one side of a piece of paper; scribble whatever it is you’re using to keep track of your possible plots (whether I, II, III, or A, B, C, or the One Where Her World Explodes, the One Where He Turns on His Left Side) down the perpendicular, and where each of them meets, make a note: in this episode, this plot will make up the A story (not the A plot—we just crept into sitcom jargon), and this one the B, this one the C, and this one’s taking a smoke break:

But ceci n’est pas un paradigme! The Grid (not a grid!) is just something you use to grasp, manipulate, note and recall the thing itself: the swirlingly fluid interplay of rising and falling actions of ever-churning never-ending storystuff braided in regular packets that nevertheless in their hurly and their burly, their ebb and flow as each crescendoes and recedes in turn to be replaced by the next already swelling, seeming thus to provide an eternally returning imitation of life at least as convincing as their illusion of change: misshapen chaos lent a decently utilitarian but deliberately none-too-well–seeming form. “It’s a fairly simple and useful charting tool for doing serial comics,” says Levitz himself, and there, that’s why it’s got nothing to do with novels, or movies, or short stories, or plays, or much of anything at all that even glances at an Aristotelian unity: this is a tool for comicbookers, soap operators, serialists: θεαμάτων διευθυντές, in the original Greek. —Novels have no need to juggle advancing and retreating plots with an abacus like this; movies-as-such shouldn’t have to twiddle plot-sliders on a giant storystuff equalizer: they’re of a shape, done in one, start to finish: there’s braiding, sure, advancing, retreating, but not on a long-term, continuing basis that requires a grid (that’s not a grid!) to track the paradigm used to keep hold of the writhing swerves of it all.

—Which is not to say you couldn’t, if you so wished, apply serialist tools to a unitary project (yes, you in the back there, a picaresque, of course, now sit down)—but much as when you set out to draw a tracking shot, you need to think a moment, at least, about how, and why, and when. —I’ve never played with the Levitz Paradigm myself, for all that I am a serialist; I can appreciate what it does, and smile to see it at work behind the shapes of comicbooks and television shows, but I don’t keep track of storylines braided in that fashion, which anyway isn’t so much a braid as a splice, or maybe a graft? (Jargon creep…) —However it is I approach the structure of my own storystuff is bound up in a synæsthetic proprioception that I can barely describe and mostly leave alone to do what it does out of fear that I’ll break something by poking at it. The way I feel it in my hands doesn’t translate to abecederial beads strung on an armature of criss-crossing wires: it’s more, I don’t know. Tidal? It does slosh. Sort of. —Anyway.

Not to go on, though, about that post (none of this is to say), a four-year-old recapitulation of an efflorescence of enthusiasm for a simple, careworn charting tool, mostly unspooled in long-since unravelled Google+ threads, which I found because I was looking for another grid, an actual grid, a fabled, magical grid:

When I started out with this I was living in a state of such terror that I would get to the end of a story and not have an ending for it, or would not have at least a satisfactory ending for it, that I would plot my stories out almost to the finest detail. If I was plotting a 24-page Swamp Thing story I would have a kind of rough idea of where I wanted the story to go in my head, I would have perhaps vague ideas of what would make a good opening scene, a good closing scene, perhaps a few muddy bits in the middle. I’d then write the numbers 1 to 24 down the side of the page and I would put down a one line description of what was happening on that page. This kind of developed to the point of mania with Big Numbers.

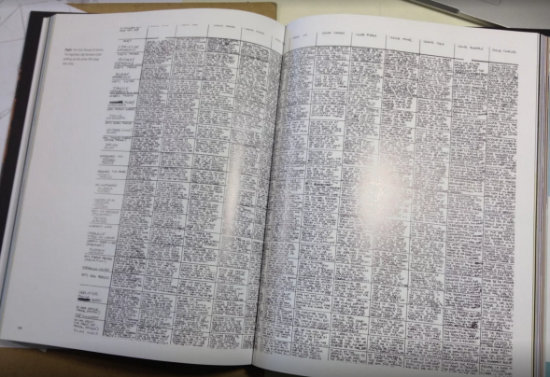

When I plotted Big Numbers I plotted the entire projected 12-issue series on one sheet of A1 paper—which was just frightening. A1 is scary—it’s the largest size. I divided it along the top into 12 columns and along the side into something like 48 different rows across which had got the names of all the characters, so the whole thing became a grid where I could tell what each of the characters was doing in each issue. It was all filled with tiny biro writing which looked like the work of a mental patient, it was like migraine made visible, it was really scary.

I mainly did it to frighten other writers—Neil Gaiman nearly shat, the colour drained from his face when he saw this towering work of madness. I’ve still got it somewhere, I just don’t look at it very often, it doesn’t make me feel good, it’s sort of: “Where was I?”

And much to the credit of that post, it offers a glimpse of the beast:

Now: that’s a grid. But it’s not a Levitz Grid. (Which, anyway, isn’t.) It’s got nothing at all to do with the Levitz Paradigm: superficially similar, perhaps (there’s the issue numbers along the top! there’s the characters, written down the side, just like possible plots!), but the plots-as-such aren’t jockeying for position, each taking their run at the top as the previous focus retires; there’s no Story A or B or C, to track and note their relative placements in time. There’s just a grid (just), a map in time, of who needs to have done what by when, to pull it all off. —Big Numbers was episodic, in that it was strictly structured around 40-page issues that had specific beginnings and endings (at least, the three that managed to make it out into the world from the shelves of Kupe’s library)—but it isn’t (wasn’t) a serial. Or at least what was serialized about it wasn’t the start-and-stop of rising and falling repeating and returning stories, per se; I mean of course it’s a serial, any writer as devoted to rhythm and rhyme and structure as Moore, any artist as formally impishly devious as Sienkiewicz, they’re going to rank and arrange elements of their work to unfold in a serial manner, yes, of course, hang the swerves on an unrelenting nine-panel grid just to show how much it isn’t, can’t be, couldn’t, repeat and return to reach for what can’t, and yet—

My specialized communicational needs exceed my grasp. (Where the words do fail.) —Christ, I caught myself just now looking up serialist composition, just to maybe have something to say it with. (Talk about jargon creep.) —I went looking for a Big Damn Example of something I might want to think about using, myself; stumbled over a post that mildly annoyed me with its innocently inaccurate enthusiasm; started to think my way through how, and what, and why, and I’ve ended up in an unlooked-for existential crisis, over what is a serial, and what isn’t, and why I think I feel as strongly as I do about this bit, or that. Or that over there, God damn.

Thus, the problem of argument: one talks oneself onto a branch that ultimately must break. I should maybe get back to the thing-that-argues? (This was all a procrastination from the thing-that-argues.)

Bombay’s a grid.

Delhi swings.

Apotheodicy.

All I wanted, all I was looking for, was some idea of what the current industry standards are, ratio-wise, height to width, for laying out an ebook page, and I know, I know, the whole dam’ point’s the fluidity and adaptability, there’s no one right true only answer, but there have to be some best practices out there somewhere—a recipe if not for grace, then something that’s more likely than not in most use-cases to end up not ungraceful. (I’d go with the golden ratio, but look at the phone in my hand—design for mobile! we’re exhorted—and you can see the golden ratio no longer so much obtains.)

That’s all I wanted, but it turns out that when you go searching for key words like EBOOK and SCREEN and RATIO you end up skirting a vast, grey-flannel field of rabbitholes lined with websites built from templates to sell you templates you can use to build ebooks with handy preconfigured placeholders into which you merely need to pour your content, crowding out the lorem and the ipsum with your marketing mission statement and your brand story and the repurposed blog posts that will build thought-leadership in alignment with your product direction while addressing the pain points of particular personas to meet the needs of your audience at a given segment of the marketing circle—or is it a sales funnel? a Klein bottle?—all while staking one’s claims to those ever-evolving SEO terms, precious as deuterium. —“Ebook,” you see, is now a term of art in marketing: a genre encompassing works more in-depth and complex than a blog post or presentation, but not so long as a white paper.

It’s one of those uncanny corners of the internet, this field: like a seemingly empty page that shows up in a search result, that turns out to have thousands upon thousands of random words tucked in a hidden div, inadvertently snagging your googling fingers; like those breathless despatches you see in the more financially minded chumboxes, from somebody with a nom de l’argent like The Points Guy, extolling the latest bestest credit cards this fiscal cycle for air miles; like that time I found out I’d been to Maui and attended a luau and written a glowing review, to the tinny approbation of supposedly fellow travelers. There’s a there there, sure—and it’s clean, tastefully lit, properly appointed, apparently well-trafficked, but still and nonetheless: clearly not for the likes of thee and me. —“Haunted” isn’t the right word; one is haunted by the absence of what once was, and this is an imminence of something that isn’t, not yet: that is desperately, hungrily, aspirationally wished-for, hoped-for, right around the corner, just you wait, balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to an image of the Singularity: the last few ergs from the only Rolls-Royce cold fusion reactor we ever manage to get online juice a sand-pocked, sun-blasted server still somehow running a couple of chatbots locked in zip-squeal conversations, in languages adversarially generated from fulfillment center stocking algorithms, all to game the odds of one of them finally talking the other into joining its proprietary multilevel marketing you i i i i i everything else

I’ve grown disenchanted with disenchantment as a metonym or symptom of the schmerz in our Welt; as the ur-wound dealt us all by the world-storm blowing from paradise. It’s a just-so story, a deeply personal tragedy ideologically smeared over the rest of us, that only seems to explain so much, all out of proportion to its brutal simplicity. —It’s not even wrong: after all, the enlightened triumph of rationalism and positivist thinking sure has left us all a surly, superstitious lot, still grimly bound by all manner of magical thought, and if God is really truly awfully dead, what are all these theocracies clashing over?

It’s a just-so story, a deeply personal tragedy ideologically smeared over the rest of us, that only seems to explain so much, all out of proportion to its brutal simplicity. —It’s not even wrong: after all, the enlightened triumph of rationalism and positivist thinking sure has left us all a surly, superstitious lot, still grimly bound by all manner of magical thought, and if God is really truly awfully dead, what are all these theocracies clashing over?

But the worst of it: by bundling up our sense of wonder, our need for enchantment, our ache for the divine, our zauberung, and telling us we’ve lost it, it’s Ent, we’ve but reified it all into a discretely graspable thing, the lack of which is now more keenly felt; by telling us all that what we want once was, in a storied, demon-haunted past, we make of all our histories a single, othered country: the very fairyland we’ve pretended to disavow. And when you’ve got a bunch of folks aching, seeking, casting about, and you tell them that beyond the fields we know is thataway—

Something hidden. Go and find it. Go and look behind the Ranges—

Something lost behind the Ranges. Lost and waiting for you. Go!

I mean, do you want appropriating colonists? Because that’s how you get appropriating colonists.

So not so much with the disenchantment, no. Now, misenchantment, on the other hand—

In McCarraher’s telling, capitalism as it has taken shape over the past few centuries is not the product of any kind of epochal “disenchantment” of the world (the Reformation, the scientific revolution, what have you). Far less does it represent the triumph of a more “realist” and “pragmatic” understanding of private wealth and civil society. Instead, it is another kind of religion, one whose chief tenets may be more irrational than almost any of the creeds it replaced at the various centers of global culture. It is the coldest and most stupefying of idolatries: a faith that has forsaken the sacral understanding of creation as something charged with God’s grandeur, flowing from the inexhaustible wellsprings of God’s charity, in favor of an entirely opposed order of sacred attachments. Rather than a sane calculation of material possibilities and human motives, it is in fact an enthusiast cult of insatiable consumption allied to a degrading metaphysics of human nature. And it is sustained, like any creed, by doctrines and miracles, mysteries and revelations, devotions and credulities, promises of beatitude and threats of dereliction. McCarraher urges us to stop thinking of the modern age as the godless sequel to the ages of faith, and recognize it instead as a period of the most destructive kind of superstition, one in which acquisition and ambition have become our highest moral aims, consumer goods (the more intrinsically worthless the better) our fetishes, and impossible promises of limitless material felicity our shared eschatology. And so deep is our faith in these things that we are willing to sacrifice the whole of creation in their service. McCarraher, therefore, prefers to speak not of disenchantment, but of “misenchantment”—spiritual captivity to the glamor of an especially squalid god.

That’s a better way, I think, to go massive, sweep it all up, things related and not, and much as with Reagan, it’s hard to go wrong when you’re blaming the Puritans (though not just them alone, God knows). But it’s still not quite right: misenchantment implies there’s a right way to go about it, that we missed; a wrong track or a foot we got off on, and all we have to do is get back on the right one, right? —And having thusly reified it, off we hare after the one right way, that unencumbered enchantment still somewhere out there, instead of looking about here and now, to what might be done to make things better (more enjoyable, more livable, more just) and not, well, worse (less; not; un).

—Malenchantment, maybe?

And, for an instant, she stared directly into those soft blue eyes and knew, with an instinctive mammalian certainty, that the exceedingly rich were no longer even remotely human.

you i i i i i everything else

Punk’d.

All of these strategies can produce terrific stories. But none seems capable of generating the sort of excitement cyberpunk once did, and none has done much better than cyberpunk at the job of imagining genuinely different human futures. We are still, in many ways, living in the world Reagan and Thatcher built—a neoliberal world of growing precarity, corporate dominance, divestment from the welfare state, and social atomization. In this sort of world, the reliance on narratives that feature hacker protagonists charged with solving insurmountable problems individually can seem all too familiar. In the absence of any sense of collective action, absent the understanding that history isn’t made by individuals but by social movements and groups working in tandem, it’s easy to see why some writers, editors, and critics have failed to think very far beyond the horizon cyberpunk helped define. If the best you can do is worm your way through gleaming arcologies you played little part in building—if your answer to dystopia is to develop some new anti-authoritarian style, attitude, or ethos—you might as well give up the game, don your mirrorshades, and admit you’re still doing cyberpunk (close to four decades later).

It was not one or two or a mere scattering of women, after all, who participated in women’s renaissance in science fiction. It was a great BUNCH of women: too many to discourage or ignore individually, too good to pretend to be flukes. In fact, their work was so pervasive, so obvious, so influential, and they won so many of the major awards, that their work demands to be considered centrally as one looks back on the late ’70s and early ’80s. They broadened the scope of SF exploration from mere technology to include personal and social themes as well. Their work and their (our) concerns are of central importance to any remembered history or critique. Ah ha, I thought, how could they suppress THAT?!

This is how:

In the preface to Burning Chrome, Bruce Sterling rhapsodizes about the quality and promise of the new wave of SF writers, the so-called “cyberpunks” of the late 1980s, and then compares their work to that of the preceding decade:

“The sad truth of the matter is that SF has not been much fun of late. All forms of pop culture go through the doldrums: they catch cold when society sneezes. If SF in the late Seventies was confused, self-involved, and stale, it was scarcely a cause for wonder.”

With a touch of the keys on his word processor, Sterling dumps a decade of SF writing out of cultural memory: the whole decade was boring, symptomatic of a sick culture, not worth writing about. Now, at last, he says, we’re on to the right stuff again.

Is something broken in our SF? Oh dear God and all those little fishes, yes, of course, indeed—but it goes so very terribly much further than the horrid enclitic. SF, as such, requires a novum new and big and strong enough to estrange us all to a cognitive breakthrough—and oh, God, the power required to effect the change we need now is so great—the responsibility demanded—we couldn’t—we couldn’t possibly—

“—I pray you, as I pronounced it to you, trippingly—”

While I was poking about, looking for what I’d said back in the day about ostranenie and the unheimlich (mostly I was trying to remember that push-me-pull-you refrain, oh I see, oh I get it, which I didn’t end up using, but make what you will of the fact I forgot), anyway, I ended up over at the Mumpsimus, contemporaneously, and saw a link in a linkdump that said, “Elves killed by punk rock,” and of course I clicked on it. —Wouldn’t you?

Magic—or more precisely, the “magical”—was one of the first casualties of punk rock. As guitar solos contracted and song structures were shaved to a stump, with amazing speed we lost our dragons, our druids, our talking trees—the whole seeping, twittering realm of the fantastic was suddenly banished, as if by a lobotomy. It survived, lurkingly, in the lower realms of heavy metal and Goth, but no one would ever again fill a stadium by singing about Gollum, the evil one. Punk rock had killed the elves.

And, well, I mean, you know what I’m gonna say about that.

Magic will not be contained. Magic breaks free. It expands to new territories, and it crashes through, barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, ah, well. There it is. Magic, uh, finds a way.

—And we can quibble about category errors and gestures and deeds and what does or doesn’t count as punk rock to a high school kid in 1987, casting about for whatever wonder-generating mechanisms are in reach, and maybe it’s less punk and more sludge, I don’t know, you can head over to YouTube to listen to the subjects of this fifteen-year-old review for yourself, but mostly the reason I’m mentioning this at all is something from the end of it, said by Dead Meadow’s singer and guitarist, Jason Simon. “These writers,” he says, “to me—”

(—he’s talking about the writers that the writer says he said are his favorites, and these writers of course are folks like H.P. Lovecraft, Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, and Arthur Machen—)

These writers, to me, are just a celebration of pure imagination. And it seems like the imagination is suffering these days—so many images coming at you, so shallow and so fast. We’re trying to create songs with some space in them, some imaginative space, to give people some room.

It’s an importantly counterintuitive point, about how the imagination suffers under the onslaught of imagination, and how absolutely vital it is to give the audience some credit.

Tripping the light.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” says the man, and, okay? I guess? I mean, I dream in English, and I’d bet he does, too, mostly, but I don’t think he means the best fantasy is written in English, I think he means the best fantasy is written in the language you grew up with, that you know in your bones, because that’s where the tricks work best: your feet think they know the stones of this path, and follow them without thinking; a clever gardener can then lay them to lead them all-unaware through shadowy copses by undrunk brooks to sudden breathtaking impossible vistas that couldn’t, shouldn’t be where they seem—and yet—

All the farm was shining with the hideous unknown blend of colour; trees, buildings, and even such grass and herbage as had not been wholly changed to lethal grey brittleness. The boughs were all straining skyward, tipped with tongues of foul flame, and lambent tricklings of the same monstrous fire were creeping about the ridgepoles of the house, barn, and sheds. It was a scene from a vision of Fuseli, and over all the rest reigned that riot of luminous amorphousness, that alien and undimensioned rainbow of cryptic poison from the well—seething, feeling, lapping, reaching, scintillating, straining, and malignly bubbling in its cosmic and unrecognisable chromaticism.

William Dean Howells wrote ten horror stories between 1902 and 1907. The stories are not highly regarded by most critics of horror; a typical comment is S.T. Joshi’s sneer that “the element of terror, or even the supernatural, in these stories, is so attenuated… that the overall effect is a kind of pale-pink weirdness entirely in keeping with the era in which they were written.”

We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” he tells us, but it turns out he’s more concerned with imminence, and evanescence, something “more real than real” that only lasts for one “long magic moment before we wake.” —And, I mean, okay, I don’t know about you, but as for me, I barely remember my dreams; I wake up knowing I have dreamed, but mostly I’m left with a (yes) color, a tone, a vector or at least a sense of motion, scraps that dissolve even as I try to pin them down, and there’s something in that grasping-after, that sense of having lost what I never knew I’d had, that gets at something in fantasy, sure, but—

“Fantasy is silver and scarlet,” he says, “indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli,” and here I’m brought up short—is that it? Why stop here? “Obsidian veined with gold,” I mean, you can find that in the bathroom of a Trump hotel. You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling:

She spoke, and the first low beams of the sun smote javelin-like through the eastern windows, and the freshness of morning breathed and shimmered in that lofty chamber, chasing the blue and dusky shades of departed night to the corners and recesses, and to the rafters of the vaulted roof. Surely no potentate of earth, not Crœsus, not the great King, not Minos in his royal palace in Crete, not all the Pharaohs, not Queen Semiramis, nor all the Kings of Babylon and Nineveh had ever a throne room to compare in glory with that high presence chamber of the lords of Demonland. Its walls and pillars were of snow-white marble, every vein whereof was set with small gems: rubies, corals, garnets, and pink topaz. Seven pillars on either side bore up the shadowy vault of the roof; the roof-tree and the beams were of gold, curiously carved, the roof itself of mother-of-pearl. A side aisle ran behind each row of pillars, and seven paintings on the western side faced seven spacious windows on the east. At the end of the hall upon a dais stood three high seats, the arms of each composed of two hippogriffs wrought in gold, with wings spread, and the legs of the seats the legs of the hippogriffs; but the body of each high seat was a single jewel of monstrous size: the left-hand seat a black opal, asparkle with steel-blue fire, the next a fire-opal, as it were a burning coal, the third seat an alexandrite, purple like wine by night but deep sea-green by day. Ten more pillars stood in semicircle behind the high seats, bearing up above them and the dais a canopy of gold. The benches that ran from end to end of the lofty chamber were of cedar, inlaid with coral and ivory, and so were the tables that stood before the benches. The floor of the chamber was tessellated, of marble and green tourmaline, and on every square of tourmaline was carven the image of a fish: as the dolphin, the conger, the cat-fish, the salmon, the tunny, the squid, and other wonders of the deep. Hangings of tapestry were behind the high seats, worked with flowers, snake’s-head, snapdragon, dragon-mouth, and their kind; and on the dado below the windows were sculptures of birds and beasts and creeping things.

“Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer,” and now I can only sigh: we were talking again just a couple of weeks ago about how flavor’s the very essence of a sylph, and to mistake the flavor for its ingredients is one of those, whaddayacall ’em, category errors; to set “rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer” as our sylphs against the (by implication) drab reality of “beans and tofu” is to not only lose the vegetarians in the audience, or those who’d quail before a cellar full of nothing but sweet wine: it loses that astounding little plate of hiyayakko we had in that strip-mall sushi joint in North Carolina, just a chilly silky geometrically perfect cube of tofu topped with flakes of ginger and slivers of scallion and tendrils of bonito and oh, that one first perfect bite, and it loses what you can make with a bag of dried black beans and a couple of cloves of garlic and salt and pepper and a cup of plonk and some water and laughter and time. —It’s precisely the same error that tells us fantasy’s only to be found in Minas Tirith or Gormenghast or Camelot, and never in plywood or plastic or (yes) strip malls. It’s to mistake the gesture for the deed, confusing the things the wonder-generating mechanisms have been attached to with the wonder-generating mechanisms themselves—my God, if you can’t conjure with a name like “Burbank,” or “Cleveland,” you’ve no business being in this business. —Multi-million–dollar empires aside.

And I know, I know: this passage is flavor text from an album intended to be carted about at conventions, collecting autographs; it was written a quarter-century ago, long before Martin’s fantasy ate the world, or at least HBO; well before the fuck-you money, which maybe helps to explain why his images of fantasy are so luxurious, drawn from Harry & David and Conran, set against beans and rice. (Oh, but that’s uncharitable, coming from me with my Japanese appetizers and cellars of peppery wines and those tricksily landscaped gardens there, up at the top.) —It’s old, and it’s slight, this passage, it’s silly, sure, but it keeps coming back—

—and silly or slight or old as it is, one of the most important lessons fantasy has to teach us is that you are what you pretend to be. The gesture may not be the deed, but performing the gesture is itself a deed, and if you keep telling us fantasy’s written in the language of dreams, that it fulfills wishes, that it gives you the tastes you yearn for and the colors you want to find again, it’s gonna raise a lot of terribly pointed questions when the fantasy you’re most known for, the deed your gesture performs, the work you put into the world is so very full of white folks and rape. —There’s something else going on here, something more, and to paper it over with something so silly and so slight is to turn those words to ash with the slightest consideration.

(“They can keep their heaven,” he says; “When I die, I’d sooner go to Middle-earth,” and, I mean, I’ve been to the Shire? Like, actually been there? Drove out on a whim fourteen years ago, when our car was new. —Whole place went under just a bit later, in the Crash of ’08.)

“The triplex, sir, is a good tripping measure;”

I’m reading Neveryóna, which is not, I hasten to add, in any way, shape, fashion, or form, a sword-and-sorcery story; it isn’t even a fantasy—it’s wholly, cheerfully, entirely SF: it’s just that the novum that estranges us past a conceptual breakthrough into a topia isn’t so much cybernetics or ballistics, but the very act of reading (in its expansive, semantic screwdriver sense) and its turn in turn to writing—

(Yes, I know there are dragons in it. That doesn’t make it a fantasy. I mean, there are dragons in Stars in my Pocket like Grains of Sand, and you wouldn’t call Pocket a fantasy, now, would you?

(Actually… Now that I think about it…

(Oh, for God’s sake, the Nevèrÿon books are [mostly, somewhat] explicitly part of the Informal Remarks toward the Modular Calculus! Which include Trouble on Triton! Which is the largest moon of the planet Neptune! And they include the Harbin-Y lectures of Ashima Slade! Who died when the gravity was cut to the city of Lux, on Iapetus! The third largest moon of Saturn! It’s SF!)

—But I digress.

I’ve been (re)reading Neveryóna, and I’ve gotten to what I remember having been one of my more favorite bits (after the Tale of Old Venn, anyway, which is a tour-de-something-or-other), when the dragon-rider, Pryn (née pryn), a “loud brown fifteen-year-old with bushy hair,” is invited to the house (castle) (cavern) (palace) (compound) of the Earl Jue-Grutn, and begins to see (as we begin to see) how intimate and implacable is the power that rules this fantastic and philosophical empire. —The earl invites her to see his collection of different kinds of writing systems, which includes on a shelf on a wall a collection of painted statuettes—

“—three cows, followed by two women bent over three pots, followed by those pyramids stippled all over; I have it on authority they represent heaps of grain—”

“And those are trees there!” Pryn pointed. “Five, six… seven of them.”

“The same authority informed me that each tree should be read as an entire orchard. The barrels at the end are most likely lined with resinated wax and filled with beer, much like the brews you help Old Rorkar produce.”

To either side of this display is a picture in a frame. The one—

“—there to the right, is inked on a vegetable fiber unrolled from a species of swamp reed.”

Pryn looked more closely: simple strokes portrayed three four-legged animals. From the curves at their heads, clearly they were intended to be cattle—no doubt the same cows that the statuettes represented; for next to them were more marks most certainly indicating two schematic, sexless figures bending over three triangular blotches—the pots.

And the other:

Left of the sculptures, in the other frame some dry, brownish stuff was stretched. On it were blackened marks, edged with a nimbus that suggested burning. “What’s this?” Asking, she recognized the even clumsier markings as even more schematic animals, people, pots, trees, barrels, grain…

“The same authority assured me it was flesh once flayed from his own horridly scarred body—he was a successful traveling merchant when I knew him, which lent its own dubiously commercial reading to the three pieces he sold me. Myself, I’m more inclined to suppose it is the branded skin of some slave’s thigh, stripped from the living leg; all too often—five times? six times? seven?—I saw my father oversee the commission of such atrocities on the bodies of the criminals among our own blond, blue-eyed chattels. From even further north than you, that scarred black man had, no doubt, as many reasons for speaking truth as he had for lying. But consider all three—”

Yes, let’s. —Delany (the earl) (Pryn) (we) rather immediately ascribe the three as art (concerned with representation, yes, but also the exercise of craft required to wring that representation from the materials chosen, or available), as writing (smooth, dispassionate, a meaning apart from the context that gives it meaning), and as pure ideological imposition, as terror, as violation, as revelation, as (?) POWER; but then rather immediately moves past these simple descriptions to a (much) more interesting question: which came first?

“Which one of the three inspired, which one of the three contaminated, which one of the three first valorized the subsequent two in our cultural market of common conceptions?”

And those of you who’ve been paying attention over the years, or who noticed the title, or can count at least to three, you’re maybe already thinking you know where I’m going with this, the maid-mother-crone, the creator-sustainer-redeemer, the Cluthian Triskelion of fantastika, the model I’ve been borrowing, the argument of the thing-that-argues, the prick against which the sermon kicks—

“Again, the initial apprehension of beauty, in an entirely different way from the initial apprehension of disinterest, redeems both modes of later inhumanity it engenders on the grounds that they are, still, misreadings—one an underreading, one an overreading certainly, but nevertheless both misguided, because impoverished, because unappreciative of the mystical, beautiful, originary apprehension which a more generous reader can always reinscribe over what the misguided two chose to inflict in terms of pain or boredom.”

—but I’m not saying that Delany’s saying (Pryn is saying) (the earl is saying) that one of these things is fantasy, and one SF, and one is horror (no)—

“Observe the three, girl. One of these is at the beginning of writing—the archetrace: but we will never know which. The unanswered and unanswerable question—that undismissible ignorance—signs my authority’s failure. And I foresee the trialogue, now with one voice silenced, now with another overweeningly shrill, now with the three in harmony, now with all in cacophony, continuing as long as people cease to speak—and all speech is, after all, about what is absent in the world, if not to the senses—before the wonder, the mystery, the confusing, enciphered presence of a written text. But certainly you have seen these..?”

—what I’m saying is, is one of these (fantasy) is trying, Ringo, is trying real hard, to recapture (recover, receive, to understand) what has been lost, by trying to represent what is in what’s available, what’s been chosen; and one of these (SF) coolly abstracts what might well could be possible from what undoubtedly is, breaking through to a brave new world; and one of these (horror) is—is—is—

Your tongue is no one else's tongue.

When I said “flavor’s the very essence of a sylph,” this is something of what I was getting at: “The first time I ate at Carbone, the nostalgia-steeped temple to red-sauce Italian that opened in 2013 in New York’s Greenwich Village, I was two Gibsons in when my penne alla vodka arrived, and I took my first bite, a transcendent roundness of cream and tomato and heat, just as the Cavaliers’ ‘Last Kiss’ started playing on the sound system. My contentment in that moment was so comprehensive, so powerfully complete, that I was horrified to realize that I was crying—weeping literal, actual tears—as I ate my meal, one of the loveliest and most profound of my life. When I came back a few months later, repeating my order to the letter, it was just a nice plate of pasta.”

Devoted to Doers and Doings.

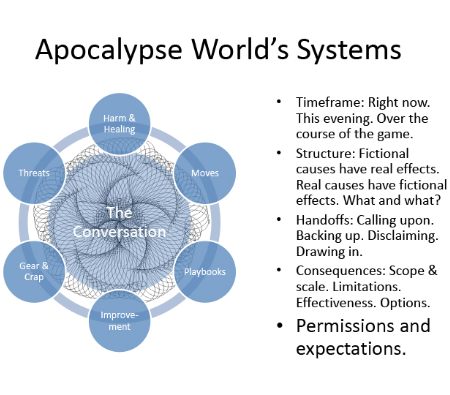

Bit odd to see a write-up in Forbes for D. Vincent and Meguey Baker, friends of the pier (and the city), and game designers par excellence nonpareil—though one is now drily amused at the thought of vulture capitalists pondering how best to monetize indie games. (They’re invited to peruse this list, to start.) —Here’s a neat presentation on (some of) what goes into being Powered by the Apocalypse; go, play.

The strengths of prose.

More writing about stuff I’ve yet to see! —I mean, I’ve heard good things from people I don’t disrespect about The Expanse on the teevee; heck, I think the Spouse has seen some episodes, but then, she is a bit more committed to life-in-space stories than I am. (I checked; she saw the first few episodes. “It had promise,” she says.) —But life is short, there’s too much to watch as it is, and between my distrust of corporate media ever being able to do anything actually good with Workers Uniting, and the vague whiff of Detective Snapbrim’s Manpain in Space, I’ve just never bothered.

As for the books: again, short life, so much to read, life-in-space, the Walter Jon Williams is somewhere in the TBR though, so there’s that, and I’ve got all those Transhuman Space and 2300 sourcebooks under my belt. —I have read some Daniel Abraham, though, who’s one half of James S.A. Corey, who writes the Expanse books, but I read him when he was MLN Hanover, and I was trying to figure out what was happening or had happened to «urban fantasy» while I was in the kitchen, getting coffee, and though I’ll always tip my hat to him—to Abraham, that is—for the pith of “Genre is where fears pool,” I’ll always then step back with a quirked brow at where he went next with that.

But! We’re not talking about lupily dhampiric gamines in Eddi and the Fey T-shirts, and we’re not talking about stylish snapbrims in space—we’re talking about adapting a work from one medium to another, and that, well—

Goodreads:

What was the biggest challenge when adapting your novels to the screen?Daniel Abraham:

The books were really written to lean into the strengths of prose. They’re full of interior monologue and clarifying exposition that just don’t work on camera at all.

—it turns out I have plenty of strong opinions about that.

To say that this or that is something so strong as the strength of something so very expansive as prose is perilously close to making an essentialist argument, and while I’d never tell you not to make one of those, one really ought to state outright what the essence is of the thing in question, and the essence of prose is setting down one word after another—which has nothing in and of itself to do with either clarifying exposition, or interior monologues. —Certainly, one can exposit or monologue in prose, and, depending on the idiom, mode, and genre in which one finds oneself, and the reading protocols thereof, and the expected and unexpected audience expectations, and whether one chooses to cleave to them, or cleave them, one may well find it an easy enough thing to do. But don’t let’s kid ourselves it’s a strength of the medium.

As to whether it’s a weakness anywhere else—

—sure, sure, you say monologue and you say cinema and you immediately think voiceover and you think theatrical cut of Blade Runner and you think you’ve won the argument, but then—

—so don’t tell me it “don’t work on camera at all.”

(As for exposition, clarifying or otherwise: one is reminded that, when John M. Ford wanted to exposit some details of dilithium in his Star Trek novel, How Much For Just the Planet?, he did so by way of the narration of an educational filmstrip titled “Dilithium and You,” but that’s a prose transcription of a visual medium inside a novelization of a television show, and I’ve lost track of where we were, and anyway Paramount changed the rules after it came out so nobody could ever do that again.)

This may seem like an awful lot to unpack from an offhand comment; Abraham’s not without his point. The expectations of any audience here and now for a series of SF books such as the Expanse allow for certain techniques that an audience here and now for an SF teevee show would balk at, and the expectations that underlie such an observation, the reasons one might put forward to explain it, could be fascinating to work through—but flatly stating that this is a just-so strength of prose, and would never just-so work on camera, utterly occludes the possibility of that work (that play).

But such a conversation is well beyond the scope of a hype interview on the occasion of a fourth-season premiere, so let’s allow as how they’re maybe just speaking imprecisely, in haste, as we all have done, and move on—

Ty Franck:

It’s also given us a chance to learn how to use the strengths of TV to tell the same story in a different way. I know Daniel had a real epiphany when he realized that all the prose tricks to convey the emotional state of a scene could be replaced with a good musical score.

—yeah. Okay. Sorry. You’re on your own with this one.

Sed quis non custodiet ipsos custodes?

If I have to hear one more goddamn television producer insist their multimillion-dollar teevee show is really, truly punk—

—I swear to fucking God—

I’m afraid that for a few years now, I have felt that since I am apparently not allowed to own the work that I created in the same manner that an author in a more grown-up and worthwhile field might expect to do, and since my protests at having my work stolen from me are interpreted by a surely young-at-heart and non-unionised audience as evidence of my “grouchiness” and “cantankerousness,” then the only active position that is left to me is to disown the works in question. I no longer own copies of these books and, other than the earnest creative work that I put into them at the time, my only associations with these works are broken friendships, perfectly ordinary corporate betrayals and wasted effort. Given that I will certainly never be reading any of these works again and that I have no wish to see them or even to think of them, it follows that I don’t wish to discuss them, sign copies of them or, indeed, have anything to do with them. As I would hope should be obvious, to separate emotionally from work that you were previously very proud of is quite a painful experience and is not undertaken lightly. However, having to answer questions about my opinions regarding DC Comics’ latest imbecilic use of my characters or stories would be much more harrowing. And, of course, it’s not as if I don’t have plenty of current work to be getting on with.

—so yeah, I was not shall we say well-disposed to the idea of a televisual sequel to Watchmen. Sure, by all accounts it was gonna be better than the last attempt to frack monetary value from the IP’s shale (but Christ, Zack Snyder is such a low bar), and I will admit my resolve (if such a curmudgeonly disdain might be dignified with such a word) weakened when I heard what they’d managed to pull off with Hooded Justice, but then I heard what they did with Laurie and Dr. Manhattan and Ozymandias and Angela Abar and Lady Trieu, and my resolve redoubled.

Should we be surprised that Damon Lindelof’s Watchmen made Lady Trieu the bad guy? That a character named after Bà Triệu, a legendary third-century nationalist hero who resisted the Chinese occupation of Vietnam, must in the end be stopped by the combined efforts of two white men associated with the genocidal destruction of multiple civilian populations (the Manhattan Project, the bombing of Vietnam itself, and the squid-fall of New York)? Should we be surprised that a show which began with an airplane dropping bombs on Tulsa provides narrative closure by thwarting Trieu’s evil plans with “a gatling gun from the heavens” fired at Tulsa? (The gatling gun, briefly used in the American civil war, and extensively used in colonial subjugation.) How did Lady Trieu, would-be avenger of colonial-violence-from-the-heavens, become the victim of yet another righteous iteration of death from the skies?

That’s from Aaron Bady’s wrap-up at the LARB, which is exactly what you’d expect from him on something like this with a title like that. —Just because I’m not gonna bother watching the show doesn’t mean I’m not going to read what people have to say about it, much as I’ve been staring agog at every Skywalker spoiler that seeps within my purview (they fucking did what now with his futhermucking X-wing?). —The one that’s stuck with me the most, most recently, has been Jaime Omar Yassin’s “Black, White, Blue”—

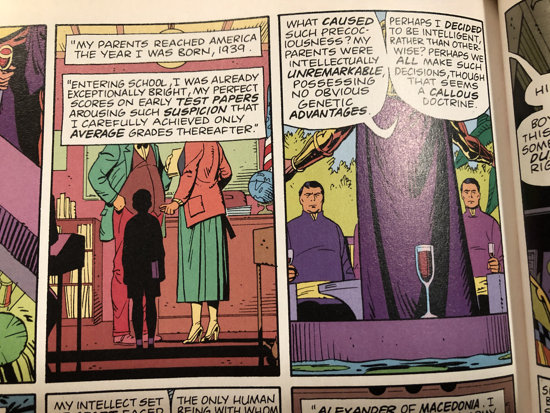

Lee characterizes the print Watchmen as a brilliant, subversive anti-racist and anti-fascist text that Lindelof’s TV show fails to live up to. I loved Moore’s Watchmen and have re-read it half a dozen times over the years, and that’s why I’m confident that the original text is a really unfortunate platform to launch these critiques from.

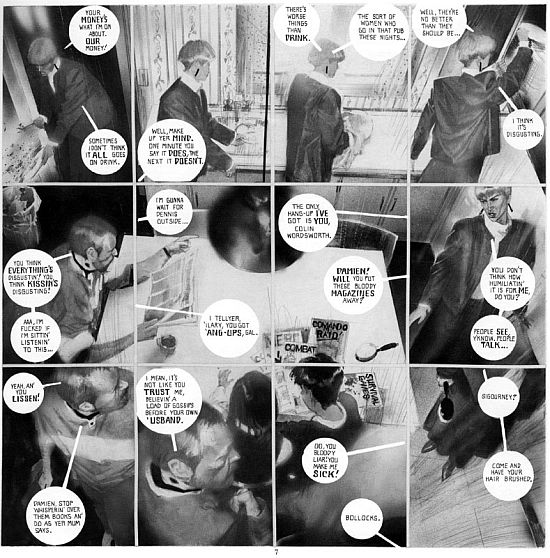

Moore built an ugly super-hero landscape, mired in imperialist politics, narcissism, cultural chauvinism and white supremacist zeitgeists, true. The birthplace of superheroing is the “Minutemen” a WW2 era group of morally-confused and easily-corrupted narcissists working under a white supremacist, capitalist definition of right and wrong who donned capes for uninspiring reasons. Moore’s work has always been about taking apart superhero tropes and putting them back together in situations atypical of the genre (1). But Moore went a few steps further here because he was able to sully the intellectual property and express his own politics about the concept. And he did it beautifully—Watchmen transcended the form with its intricate plot and a reverberating flow of prose and art. All indisputable.

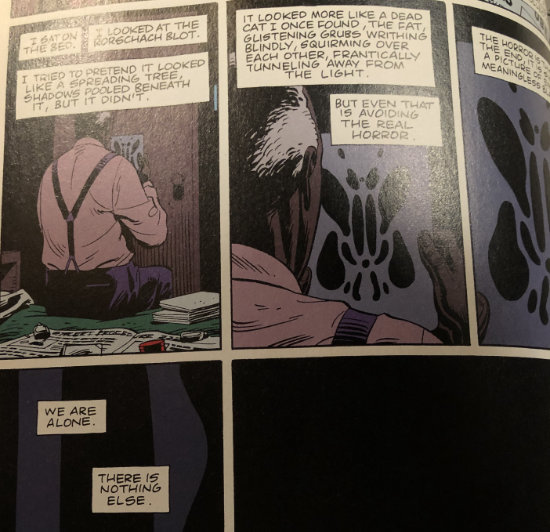

Regardless of his intentions, however, Moore built a thematic framework that bolsters many awful superhero tropes—and these have outlived the subversive qualities of the text (2). Moore, to his credit, created dynamic three-dimensional characters, and that’s the problem. After all is said and done, Dr. Manhattan is a mass murderer indifferent to human suffering. Rorschach, a proto-incel, is an Alex Jonesian conspiracy-fabulist. And yet fans—like me—loved them both for decades. Moore had us spend so long in the heads of Manhattan and Rorschach that eventually their world-views became compelling.

Omar deftly explicates the comic’s whiteness, and its failures to address race and racism (despite its aims and goals), and ties this to a general pro-police tenor in Moore’s work—surprising, to be sure, in an anarchist; less so, perhaps, in a writer of superhero comics: and this, I think, is where the dam’ whole enterprise falls down: “The fail condition of subversion/parody is reification.”

But I want to dig into one thing Omar brings up that reveals just how heartbreakingly Watchmen fails, or was failed—

Rorschach is every bit the reactionary Miller’s Batman is, but Moore’s superb narrative tells us why in a compelling and heart-breaking flashback. Ironically, Rorschach’s lengthy existential thought balloons (and those of Dr. Manhattan) feed into conservative ideas about a dark nature of humanity with a far greater lasting effect than Dark Knight Returns. Moore compounded this by taking Rorschach’s side in philosophical debates. When a “liberal” African American prison psychiatrist must treat Rorschach, it’s Rorschach’s perspective that infects him, not the other way around. Rorschach is shown to have the more compelling, self-aware view, while the psychiatrist is a liberal fop, as weak as Rorschach implies when he reads him. Moore—unlike Miller who actually got worse (3)—moved on from treatments of superheros in the decades after Watchmen, I suspect because he recognized the perils of even engaging the tropes (4).

Aaaaand—I mean, it’s not that this isn’t not what doesn’t happen, and it’s not that Dr. Malcolm Long isn’t a liberal fop, a milquetoast, even, and it’s not that he’s not infected by Rorschach’s nihilism. But that’s not the end of Long’s story.

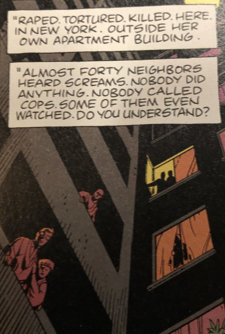

Rorschach’s (Kovacs’) “compelling and heart-breaking flashback” is, of course, built around, based upon the Kitty Genovese story—not what actually happened, but the story—

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

(And as a brief digression, the shot here, of neighbors watching from the balconies of apartments supposedly on Austin Street in Kew Gardens, Queens, New York, lends some slim credence to the mildly contested theory that Moore tripped over the story of Kitty Genovese by way of Harlan Ellison’s “Whimper of Whipped Dogs,” which, I mean, I know I first heard the story of Kitty Genovese by way of an Ellison essay, I think, in The Glass Teat, I think, which is one more I owe the bastard, and anyway, I agree with Joanna Russ—but let’s face it, the story of Kitty Genovese is everywhere.)

—though I must admit a moment’s amusement, reconciling the queer bar manager who was, with the socialite who was supposed to have been, who rudely rejected the pop-art op-art dress that ended up becoming what would be Rorschach’s mask.

It’s pointless to argue whether 38 or “almost forty” neighbors really heard the socialite’s screams, or if it was more like what really happened; what happened that was compelling and heartbreaking was that Kovacs read an article in the New York Gazette that said that’s what had happened, which is what inspires him to make his mask and dress up as Rorschach and go and fight crime as a costumed adventurer né superhero—“I knew what people were then,” he tells Dr. Long; “behind all the evasions, all the self-deception. Ashamed for humanity, I went home. I took the remains of her unwanted dress and made a face that I could bear to look at in the mirror.”

And Dr. Long hears that and tries to dismiss it and feels badly about trying to help Rorschach or Kovacs out of somewhat selfish reasons and has movie-of-the-week arguments with his wife about the damage his dedication to his job is doing to their marriage, and in the end he breaks on the bulwark of Kovacs’ or Rorschach’s next, real origin story, which I bet Zack Snyder got a kick out of filming—but that isn’t the end of Long. It’s just the end of chapter six. (Of twelve.)

No, Long’s end comes at the end of chapter eleven: as Ozymandias’s stupidly huge plot comes to fruition, a number of uncostumed unadventurous unsuperheroes whom we’ve seen here and there in the previous chapters milling about the business of their lives as the protagonists protagonize, these folks end up converging on a corner by Bernard’s newsstand near Madison Square Garden, Dr. Long, and Bernard (of course), and Bernie, Derf, Detectives Steven Fine and Joe Bourquin (cynical cops who in the end get to prove they’re good police, but I anticipate myself), Milo, Gladys Long, and Joey and Aline, and the point is, what happens is, when Joey and Aline get into a fight over their dissolving relationship, and when Joey attacks Aline, pushes her to the ground, starts kicking her, right there, on the sidewalk, before the newsstand, all those onlookers, those neighbors, less than 38 or almost 40, sure, but Bernard and Detective Fine and even yes Dr. Long, despite his infection with Rorschach’s nihilism, he steps up with the rest of them all to stop the fight, and that’s the end of Dr.Long, and all of them: a spontaneously anarchist fellowship, a striking reversal of a superheroic origin, a repudiation of all the cool grimdark Rorschach supposedly serves up as truth, a pro-Genovese anti–Genovese-story—

—that gets smashed in the very next instant, bigfooted by the squid-drop climax of the protagonists’ plot.

But! This ironic thematic climactic crescendo itself gets bigfooted by everything that happens around and about that squid-drop: the superhero-cool in Antarctica, “I did it thirty-five minutes ago,” Dr. Manhattan’s apotheosis and Ozymandias catching bullets and Rorschach in the snow. The book’s supreme irony—that the human fellowship Veidt despaired of is obliterated precisely by the plot that Veidt engineered to restore it—is itself ironically overwhelmed by the superheroic armature of that plot. So much so that almost no one who talks about it ends up talking about this at all…

I said this recently but I think the best part of the comic is all the background characters coming together to try to stop a fight in Times Square, on their own, no capes. https://t.co/iuyO0U5vMe

— Gerry Canavan (@gerrycanavan) December 9, 2019

…so that’s another way that Moore and Gibbons failed the comic (not so much Higgins, he’s still cool), and the comic failed the show, and the show failed us all, and as for us?

The Fanonian Watchmen is there, but buried deep. By quoting from the “The Internationale,” Fanon’s title gives to the Wretched of the Earth the implied imperative to “Stand up,” but Lindelof’s Watchmen submerges any revolutionary consciousness under things like the cartoonish “Red Scare” character. The only masses in the show are white supremacists. Still, if you look for it, you can find in the story of Angela and her grandfather the discovery that America’s problem is not hidden conspiracies to be revealed but the open secret of American white supremacy; if you want, you can trace out the show as it might otherwise have been, in which two granddaughters of American massacres team up to create a better world from the ashes of what was done to their families.

We’re left once again to ignore the ending we’ve been given, and imagine something else.

(Oh but one last ever-loving thing: learning that Lady Trieu’s villainous genius was explained and excused by her descent from Veidt was enough to make me want to throw the goddamn television show across the goddamn room. Why—that would be as astoundingly short-sightedly stupid as the Star Wars people deciding that instead of being her own person, Rey would have to be excused and explained by her descent from someone like Emperor Palpatine, I mean, can you imagine? —Can you imagine something else? Something different? —At all?)

Minimally viable product,

or, Easy money at the ketchup factory.

“The books are wretchedly written, but fast-moving. The wretched prose, the mixed syntax, the bad grammar, and the typos would barely raise a sneer from the MFA-educated crowd. They’re used to a publishing industry that already embraces James Patterson and Dan Brown’s barely literate level of storytelling. The bar was already low; it’s just being slid through the wood chipper and scattered over the culture like salt at Carthage. —I looked up Anderle’s record on Amazon. His Author Rank is #54 in the Horror category, placing him ahead of Lee Goldberg, Seth Grahame-Smith, and some guy named “Richard Bachman.” In Science Fiction, he’s ranked #60, ahead of Alan Dean Foster, John Scalzi, Douglas Adams, and Neal Stephenson. —But if you feel that Anderle’s work represents the bottom of the barrel, you haven’t met T.S. Paul.” —Bill Peschel

This storm is what we call progress.

Many of the great fantasy writers of the last century were shaped by the experience of World War One; the attitude of JRR Tolkien to the world storm of his time is anguish and anger; he and other great fantasy writers turn away from the world to shame it. Here are the four phases:

- Wrongness. Some small desiccating hint that the world has lost its wholeness.

“With each set of three books, I’ve commenced with a sort of deep reading of the fuckedness quotient of the day,” he explained. “I then have to adjust my fiction in relation to how fucked and how far out the present actually is.” He squinted through his glasses at the ceiling. “It isn’t an intellectual process, and it’s not prescient—it’s about what I can bring myself to believe.”

- Thinning. The diminution of the old ways; amnesia of the hero and of the king; the harvest fails, the Land dries up; diversion of story into useless noise; battle after battle.

After The Peripheral, he wasn’t expecting to have to revise the world’s F.Q. “Then I saw Trump coming down that escalator to announce his candidacy,” he said. “All of my scenario modules went ‘beep-beep-beep—super-fucked, super-fucked,’ like that. I told myself, Nah, it can’t happen. But then, when Britain voted yes on the Brexit referendum, I thought, Holy shit—if that could happen in the UK, the US could elect Trump. Then it happened, and I was basically paralyzed in the composition of the book. I wouldn’t call it writer’s block—that’s, like, a naturally occurring thing. This was something else.”

- Recognition. The key in the gate; the escape from prison; amnesia dissipates like mist, the hero remembers his true name, the Fisher King walks, the Land greens. The locus classicus of Recognition is Leontes’s cry at the end of The Winter’s Tale (1610) on seeing Hermione reborn: “O she’s warm.”

In the hall, he relieved me of my misjudged chore coat, and handed me a recent reproduction of Eddie Bauer’s 1936 Skyliner down jacket: a forerunner of the down-filled B-9 flight suit, worn by aviators during the Second World War. Boxy and beige, its diamond-quilted nylon was rigid enough to stand up on its own. When I put it on, it made me about four inches wider. Gibson shrugged into a darkly futuristic tech-ninja shell by Acronym, the Berlin-based atelier, constructed from some liquidly matte material.

“You have to dress for the job,” he said.

- Return. The folk come back to their old lives and try to live them.

She doesn’t zoom through glowing datascapes; instead, having suffered from “too much exposure to the reactor cores of fashion,” she practices a kind of semiotic hygiene, dressing only in “CPUs,” or “Cayce Pollard Units”—clothes, “either black, white, or gray,” that “could have been worn, to a general lack of comment, during any year between 1945 and 2000.” She treasures in particular a black MA-1 bomber jacket made by Buzz Rickson’s, a Japanese company that meticulously reproduces American military clothing of the mid-twentieth century. (All other bomber jackets—they are ubiquitous on city streets around the world—are remixes of the original.) The MA-1 is to Pattern Recognition what the cyberspace deck is to Neuromancer: it helps Cayce tunnel through the world, remaining a “design-free zone, a one-woman school of anti whose very austerity periodically threatens to spawn its own cult.” Precisely because it’s a near-historical artifact—“fucking real, not fashion”—the jacket’s code can’t be rewritten. It’s the source code.

I think it’s inarguably clear: we must admit William Gibson to the ranks of the world’s great fantasists.

—30—

“This is the violence that endings do to stories,” says Aaron Bady, writing over at Dear Television about the final season of Game of Thrones; come for his epic musings about the longue durée, sure, which get at how we go about doing what we do, but stay as Sarah Mesle namechecks the smoldering appeal of Tanthalas Quisif Nan-pah, which gets at some of the all-important why—wait a minute. Strike that. Reverse it; thank you. (—The commenter who insists “you cannot directly comment on the real world with fantasy and every one who thinks so is a pompous idiot” would be the lagniappe.)

[ insert some sort of multiple face-palm gif, or maybe the one with Nathan Fillion, and his hands ]

Here’s a question the NEA literature staff has been thinking about lately: what do you call a literary title that infuses text with art and is primarily geared toward grownups? A graphic novel? Picture book? Art book? Illustrated book? Or, as the poet Matthea Harvey suggested to me recently as we sat and discussed the matter over brunch, a “tart” (text + art)?

I, I don’t, I just—how about we, maybe we just call them comics? —Unless they aren’t?

And if they aren’t? I don’t know, maybe don’t listen to someone who doesn’t care to tell the difference between medium, idiom, and genre—poetry’s a medium, after all, and intermingling (or co-mixing) pictures and verse would be an idiom thereof, and as for genre, well, that’s apparently mostly useful for figuring out which shelf Citizen ought to be put on, to move more units, or which tags should be used, to maximize SQL query returns, and in the face of such generic concerns the particular instantiation of a singular work such as this seems—

—small?

—unimportant?

—no, wait, those aren’t the words—

To yelp, or not to yelp.

“What happens to our notion of humanity if Hamlet just takes out his smartphone and asks Siri what to do?” Nothing. Not a goddamn thing. —Christ, where do they find these people?

You an’ me both, kid.

“As soon as he left, Velásquez spoke and said, ‘I have tried in vain to concentrate all my attention on the gypsy chief’s words but I am unable to discover any coherence whatsoever in them. I do not know who is speaking and who is listening. Sometimes the Marqués de Val Florida is telling the story of his life to his daughter, sometimes it is she who is relating it to the gypsy chief, who in turn is repeating it to us. It is a veritable labyrinth. I had always thought that novels and other works of that kind should be written in several columns like chronological tables.’” —Jan Potocki