Hope is not a plan.

Point is—I come from a generation of young liberals who, after the relative coddling of a Clintonian childhood, were horribly crushed by election outcomes. Not once, but twice in a row, with 9/11 in the middle (my 18th birthday was two days before).

I strongly suspect that we will be forever a little messed up by having come of age in what might prove to be a peak period in world prosperity, relative international calm, and predictable disappointments—followed so abruptly by trauma after trauma after trauma.

I recall, probably around spring break of 2002, sitting with my father (well-weathered by the injustices of the world) and watching the sunset together, my mom’s extended family chattering around us, and quietly telling him, “I just want to know that the world is going to be okay.”

And for the first time ever, he told me, “Well, Dylan, it’s not.”

David Simon (yes, that David Simon) shows up in a comment thread to say much the same thing (if not as succinctly) to Matt Yglesias, who feels Simon’s vision of bleak urban dystopia is counterproductive to advancing the values we hold dear:

Writing to affirm what people are saying about my faith in individuals to rebel against rigged systems and exert for dignity, while at the same time doubtful that the institutions of a capital-obsessed oligarchy will reform themselves short of outright economic depression (New Deal, the rise of collective bargaining) or systemic moral failure that actually threatens middle-class lives (Vietnam and the resulting, though brief commitment to rethinking our brutal foreign-policy footprints around the world). The Wire is dissent; it argues that our systems are no longer viable for the greater good of the most, that America is no longer operating as a utilitarian and democratic experiment. If you are not comfortable with that notion, you won’t agree with some of the tonalities of the show. I would argue that people comfortable with the economic and political trends in the United States right now—and thinking that the nation and its institutions are equipped to respond meaningfully to the problems depicted with some care and accuracy on The Wire (we reported each season fresh, we did not write solely from memory)—well, perhaps they’re playing with the tuning knobs when the back of the appliance is in flames.

Does that mean The Wire is without humanist affection for its characters? Or that it doesn’t admire characters who act in a selfless or benign fashion? Camus rightly argues that to commit to a just cause against overwhelming odds is absurd. He further argues that not to commit is equally absurd. Only one choice, however, offers the slightest chance for dignity. And dignity matters.

All that said, I am the product of a C-average GPA and a general studies degree from a state university and thirteen years of careful reporting about one rustbelt city. Hell do I know. Maybe my head is up my ass.

That thread in general is well worth your while beyond Simon’s pith; I’ll just highlight one other, inconclusive comment, and leave it at that:

I clerked for a very conservative federal judge who was known in our district as the “hanging judge.” He was a huge Wire fan and his sentencing/judging really changed for the better since he started watching the show. Of course, I don’t know if it was the show for sure; but his view and treatment of the people coming before him changed dramatically.

Fascists are people;

Liberals are people;

∴ Liberals are fascists.

Yes, another blip about Jonah Goldberg’s very serious, thoughtful lump of horseshit that has never been smeared across the public discourse in such detail or with such care. —Over at Unfogged, Bob McManus thinks Jonah deserves serious consideration, and while my immediate impulse whenever anyone asks why we aren’t taking it seriously is to point to Bérubé (his lunch with Horowitz; more en pointe, his Goldberg variations), let’s, well, take McManus seriously:

“You think Jonah deserves serious consideration”

Yes I do. If I were a progressive blogger, I would look at the book and wonder what was being taken off the table rather than what was being put on the table. I would meta and Strauss the damn thing. He had a purpose. He is getting paid.

And yes, Jonah has a purpose; Jonah did, indeed, depressingly enough, get paid for his fumbling assault on language and critical thought. But his purpose is simple enough to discern: he’s out to degrade any attempt at defining and situating fascism. What’s he’s trying to take off the table are Umberto Eco’s 14 ways of looking at a blackshirt, replacing them with nothing more than a bulge-eyed spittle-flecked bellow of “Fascist!” in a crowded theater. And if you’ve followed the links above, you already know why he’s trying to do this: Bérubé, that prancing jackanapes, told you plainly enough:

So if Jonah Goldberg’s project is to show that liberalism is the new fascism, it probably makes sense to ask whether there’s any old-time fascism running around somewhere while the doughty Mr. Goldberg mans the perimeter.

Over at Sans Everything, Jeet Heer does what little spadework’s necessary to demonstrate that Jonah’s own National Review has been steeping in precisely that old-time fascism for years. —Thus does Jonah’s 496-page argument collapse: no longer a brutally clever attempt at shifting the Overton window, it stands revealed as nothing more than a desperate bleat of “I know you are, but what am I!”

It stands revealed, yes, to those that read; but only those who already know will read. —How do you reach someone who believes what Jonah’s said? Or at least professes to believe?

I’m stuck in the koan. —On the one hand, of course this assiduous furore of taking-unseriously isn’t an attempt at argument per se. Posting clips from A Fish Called Wanda won’t convince anyone who isn’t already in your corner of anything; nor will baldly proclaiming that the new fascist stormtrooper is a female grade school teacher with an education degree from Brown or Swarthmore. They’re tokens and dogwhistles in a playground slapfest, and the best you can say for us over them is we’re less likely to pretend otherwise. “Taking Jonah seriously” doesn’t work on the playground; all we can hope for is damage control. —To the extent they aren’t spontaneous upwellings of disgust, or hails and hearty laughter shared with weary fellow travelers, or attempts to spit in Jonah’s coffee, our salvos and volleys strive inch by inch to effect our own Overton shift: to achieve some critical mass and attach some small measure of shame to the name of Jonah Goldberg, so this media outlet or that think-tank venue might think twice before inviting his participation, and his opportunities to play his tokens and sound his dogwhistles might thereby be lessened. If only a little.

On the other, we win to the extent we can by increasing the us and decreasing the them. It’s hard to do that when you’ve grabbed them by the lapels and you’re smacking them in the face with their own dam’ book and you’re bellowing “Stop hitting yourself! Stop hitting yourself!”

Harsh, yes, but also unfair.

It only just now occurred to me: Alan Moore’s (and Kevin O’Neill’s, yes yes) Black Dossier is really his Number of the Beast.

Drive-by kulturklatsch.

I’m needed elsewhere; I’m trying to Get Things Done. (Never mind the sooty faces tugging at the Forge!) —This is mostly me using the Outboard Brain. And so: this (which found via this) seems somehow to me to be saying something, what, obverse? to this, which is (indirectly) about this. (I’d add something about the stagnation of the direct market in comics as everyone waits for trades that never come because the floppies don’t sell, but I’m not sure where to put it.) So: no thought, just bookmarks. (On a seemingly unrelated note: should I kill the joke about the three lions entirely? I mean, head, hand, and heart, but who the fuck’s gonna follow that?)

More on the behemoth.

Dylan, as ever, says it best. —Meanwhile, Momus is trying to take the piss out of Potter and The Wire at the same time, and for such an intellective jackanapes falls distressingly flat. Announcing to the world that you think the point of a name like Severus Snape is “you don’t have to waste much time working out whether they’re good or evil” is to mistake the set-up for the punchline, and if you require nothing more than a weepy third party’s word to accept that Bubbles must be “the most sympathetic character ever to appear in a TV drama,” well, you’re pretty much doomed to repeat the downfall of Tom Townsend, who never read novels, just good criticism, thus to efficiently garner the thoughts of a critic as well as the novelist.

—Ah, well. Momus is not without his point re: “wholly human,” and at least it’s—wittier? more insightful?—better than Ron Charles’ weary screed about how it’s all not really, you know, reading.

—racing down tracks going faster, much faster—

Immanentise the eschaton!

You let the eschaton alone. It’ll come in its own good time.

—Competing grafitti noted in the neighborhood of I want to say Glastonbury

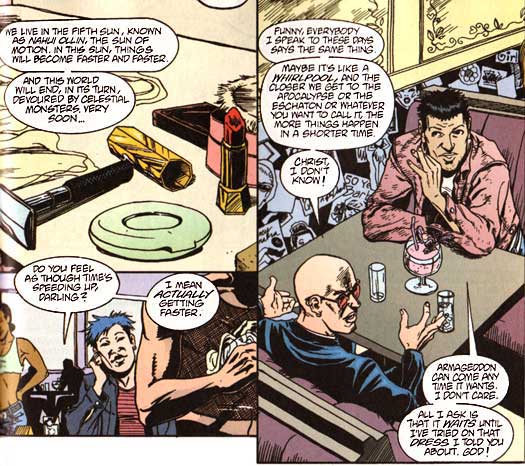

Set out, set out. —But there’s a couple of things that ought to be explained first, like how magic works; right now, I want to talk about a hitch in the body of time. Lord Fanny and King Mob, drawn by Jill Thompson, hanging out in a diner:

And it is, isn’t it? Getting faster. All the time.

But this has nothing to do with eschatons or apocalypses, armageddim or fifth suns. There’s no damn whirl; no damn pool. It’s all so much simpler than that. There’s just us, and here, and now, and the aforementioned body of time. —The thing about time being that your immediate, visceral sense of it, the time that has actually flowed over and past you, your experience of it, your experience, well, that time is always the same size and the same shape, once it’s set (and rather early on): it’s always the size of your life. (“No more, no less,” to tap another echo elsewhere.) As you get older, as you pack more hours and days and years into the same little box, each one is necessarily left with a smaller slice of the whole.

Pitiless, perhaps, but that’s math for you. —“See,” said my littler sister, when she told me this, “a year is like a twelfth of my life. But it’s like a twenty-fourth of yours.” Grinning like a canaried cat in the back seat. (She had every reason to, of course. Already my years were smaller, harder to see, easy to lose in the crowd. It’s only gotten worse.) —Of course everybody King Mob speaks to has been saying the same thing. Everyone ever has always said the same thing. It’s always already been getting faster.

Keep this hitch in mind, and you’ll be able to answer certain questions like a chuffed Robert Graves: why there’s always jam tomorrow and jam yesterday, for instance, and never jam today. Why every Golden Age is the same Golden Age, and where the Old Skool was; when the Eschaton will strike; where Armageddon will have been.

Forget it, and you fall prey to the anthropic fallacy—the lie of the one true only. Like a smug Frank Tipler, you’ll think that here and now is special because you’re here and now; you’ll think you can say for sure when the jam will arrive; you’ll believe it’s all finally coming to pass and in your time; you’ll know in your bones that time is actually getting faster, because every year to you seems shorter than the year before.

The funny thing about The Invisibles is that while the plot depends upon this fallacy—time really is speeding up, just as Fanny says; the age of the fifth sun is about to end in whirlpools and apocalypses, and the crowning of a dark Lovecraftian king in Westminster Abbey during a solar eclipse—but the point of The Invisibles is precisely opposite: we all immanentize the way we die: alone. Our initiation is always already about to begin; it’s never not the Day of Nine Dogs, and Gideon’s last phone call is the same as Wally Sage’s, to tap another echo, elsewhere again. (Or Jack Frost, with Gaz in his lap. —Of course there’s a plot! Of course the plot must have such a ridiculous, action-packed climax! It’s all a game, remember? Sucked from an ærosol can. Go back and play it again!) —The fact that you’re in the here and now doesn’t make this here, this now any more special than any other slice of eternity—except, that is, of course, to you. And every hour that passes you by makes every other hour that much the smaller, the faster, much faster, until they never let us out ten blocks later.

—Thus, the hitch in the body of time.

I’m hurting cultchah!

Confidential to Keen in Silicon Valley: dude, I know, he made a lot of money, but you start citing George Lucas as some sort of, Christ, I’m not sure what, a compeer of David Hockney or something, some sort of authority on art, well, you’ve pretty much gone and shot your argument in the face. (via; via)

What do you think of Internet video? Lucas says there are two forms of entertainment: circus and art. Circus is random, he says: “feeding Christians to the lions”—or, he says, as the term in Hollywood goes—”throw a puppy on the highway. … You don’t have to write anything or really do anything. It’s voyeuristic.” In short, he says, it’s YouTube. Art is not random, Lucas says. “It’s storytelling. It’s insightful. It’s amusing.”

All models are wrong. Some are useful.

We’re finally watching Rome. —At some point during the second episode, I say something like, “So it’s Artoo and Threepio.”

And then a little later, the Spouse says, “I’m still trying to deal with the idea of Threepio as a whoremonger and Artoo as a stolid family man.”

I frowned. “No, wait,” I said. “Threepio’s the uptight prig, right? Artoo was the id-guy.” The collapse and reversal shorted something in my brain. I grinned. “So, like, Molly’s Threepio, right?”

—Maybe you had to be there.

Magical white boy.

Oh, hell, let’s chase the red herring for a minute. I’ve got time; I’ve got nothing but time. —So: no. Morpheus is not a magical negro. If nothing else, his touchingly stubborn faith in Neo, which sets him at odds with the magical Oracle, which causes us to doubt him (though we never doubt he’s right: Neo must be the One—look at his name!), and which even causes him to doubt himself—this grants him a degree of agency and protagonism that sets him apart from the mere role of wisely aiding and abetting Neo’s enlightenment. (To say nothing of his captaincy, his popular acclaim in Zion, or the fact that he’s the one who lives to tell the tale—)

So: the One True Neo, a man with almost no past, prone to criminality and laziness, inwardly disabled by his shyly geeky nature, hated as a hacker by the powers that be, granted a terrible power so close to the very nature of things yet tempered by his need to help others, ultimately sacrificed, and all to aid Morpheus in realizing his dream—

Well, yes. That’s why the movies, flawed though they indisputably are, nonetheless have the power they have.

But I wasn’t really thinking about the red herring. I was thinking about Mercutio, and I was thinking about Nick.

—Why was I thinking about Mercutio? Right. Because we’d just finished the second season of Slings and Arrows, with its hilarious production of Romeo and Juliet running under and around the A-plot of Macbeth. Why was I thinking of magical negroes? Because I’d stumbled over MacAllister’s LiveJournal, and the most recent entry over there is a nice-enough trip through the trope. And why was I thinking of Nick?

Well, first, Mercutio; specifically, given the confluence of topics, Harold Perrineau’s, in the deliriously ludic Baz Luhrman production. Ostensibly Romeo’s foil, Perrineau’s Mercutio practically foils the whole damn film, othered to his very gills: the only black character, his gender bent in an otherwise rigidly stratified world, his sexuality—well. Even the lightest brush of those buttons with Mercutio—witty, articulate, prancing Mercutio, always a snappy dresser—leaves little room for doubt. —Forever outside the discourse of both those houses, he pushes and pulls and chides his charge until Romeo sees the light and gets off his goddamn ass, and as far as magic goes, well. Queen Mab, bitches. Those drugs are quick.

But hard as they might push in that direction, and as much power as they might arguably draw from the trope, and despite his Act III Scene 1 sacrifice, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Mercutio could ever be anyone’s magical negro.

(A conscious piss-take? I doubt it; I highly doubt it, if for no other reason than Spike Lee’s eponyming talk came five years later. —But Uncle Remus has been with us for a long, long time. Even in Australia.)

Nick, of course, Chris Eigeman’s Nick, is the Mercutio of Metropolitan, othered by his cheerfully chilly snark, his abiding concern for times and fashions past, his detached perspicacity—though perched in the very catbird seat of privilege, he is nonetheless, within his own context, his insular circle, despised; though his power is mighty (he creates a person from whole cloth, like New York magazine) and his scorn withering (ask a bard what terrible magic satire can wreak), he does little beyond push and pull and chide his Romeo, Tom Townsend, over the barest threshold of the story. (He does also insult a Baron, and start a cha-cha.) —And though he isn’t sacrificed, per se, he does abruptly leave the story toward the end of the second act (of three, of course, not five), marching stoically off to his comically supposéd doom.

But much as it might tickle me to push this WASP in that direction, there’s no way in hell or out of it that Nick could ever be a magical negro.

And not because he’s so very, very white. Well, yes, of course, but—

Nick’s a foil, like Mercutio: slipped under the gem of the protagonist to catch the light and throw it back, up and through the protagonist’s facets, the better to shine for our delectation; necessarily subordinate to the protagonist because it’s all about the protagonist. Isn’t it? —They are othered because the protagonist is by definition normal, and they must stand in contrast. They leave so suddenly because the protagonist, having been pushed, must in the end do it all alone. It is, after all, the protagonist’s story.

Yet ask an actor who they’d rather play.

There are foils that disappear behind their gems, that bow and scrape their way across the stage, that take so literally the story-mechanics of their function—to assist the protagonist, buff and polish them till they shine—that they reify those rude mechanics within the story itself, black-garbed kabuki janitors shoving the machina in place for the fifth-act emergence of a pure white deus, and they perform these tasks with little more than a wide wise smile to hint at a there in there, somewhere. And there are settings so rich and strange and wondrous that the very question of who is a protagonist and who isn’t becomes a trick of where your eye happens to light first, and what you make of it. —Nick and Mercutio fall within that spectrum (there is no doubt as to the protagonists of their stories: not them), yet much closer to the one end than the other: no mere enablers, but so very much themselves, so selfish that they’d never be mistaken for the help.

(And because they stand so flashily in contrast to protagonists who must, as noted, be so damned normal [though admittedly not too normal, in either case], a little of the life of the proceedings can’t help but leak out when they leave. There’s a lesson there, too: like all good blades, this stuff cuts both ways.)

—One final digressive note, which draws a little on the related though much less prevalent trope of the magical faggot (think for a moment of the queer eyes buffing and polishing their protagonist; now let’s move on), and specifically the o’erwhelming need for queer foils to die in order to balance out on some inhuman scale the racy transgressions they commit to foil whatever they’re foiling; more specifically, the storied death of Tara, from Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which Mac (most specifically) brought up in passing at the end of the post that’s one of the wellsprings for this one: well. It’s at once rather a bit less complicated than that, and rather a bit more.

The one true only.

And so we return and begin again.

You know, human batteries aside, I enjoyed The Matrix well enough right up to the very end, you know, the Nebuchadnezzar’s blowing up all around them, those electric jellyfish beating their way in, Neo lying flatlined in the cradle, Hugo Weaving with his gray-flannel smirk, and Trinity leans over Neo and says something like, “Neo—I’m not afraid anymore! The Oracle told me—”

Yes?

“—I would fall in love, and that man, the man I loved, would be the One. So you see, you can’t be dead, you can’t be—because—”

Oh, no no no no no. That’s not what the Oracle told her, dammit. Should have told her. Could have. Would have. What the Oracle should have told her is what the Oracle should have been telling every-damn-body:

You’re not the One. Not yet. Sorry, kid. Looks like you’re waiting for something. Your next life, maybe. Better luck next time.

Still bugs me, thinking about that.

Well, the human batteries, and that shoot-out in the lobby. Gratuitously nasty round of best-man-fall. That little gesture to fix the sunglasses, trying to remind us it’s only a game. —Doesn’t work, somehow.

I am interested in your product or service, and I’d like to hear more.

A quote from Trilling; head over to Kugelmass for context:

As we read the great formulated monuments of the past, we notice that we are reading them without the accompaniment of something that always goes along with the formulated monuments of the present. The voice of multiplication which always surrounds us in the present, coming to us from what never gets fully stated, coming in the tone of greetings and the tone of quarrels, in slang and in humor and popular songs, in the way children play, in the gesture the waiter makes when he puts down the plate, in the nature of the very food we prefer… And part of the melancholy of the past comes from our knowledge that the huge, unrecorded hum of implication was once there and left no trace—we feel that because it is evanescent it is especially human. We feel, too, that the truth of the great preserved monuments of the past does not fully appear without it.

Bruises and roundhouses.

This may just be a pattern in search of a theory that is itself in search of a problem, but it struck me in the shower and hasn’t gone away, and so I give it a wipe and a polish and set it down before you. “It” being: the notion that there might be if not an essential difference between the pulp heroics of prose and the pulp heroics of comics (because, let’s face it, everything is essentially the same dam’ thing) then perhaps a perceptible difference: what is heroic in a prose pulp hero will tend or drift or gesture toward the done-to, the withstood, the survived, the masochistic; what is heroic in comics pulp will tend or drift or gesture toward the done-by, the delivered, the unleashed, the sadistic.

Not to freight our gestures or drifts or looks too heavily or anything. Pattern, theory, problem. —But think of James Bond (in the books), think of Travis McGee: the scars they display; the pain suffered so exquisitely during and after every fight. Think of Spider-Man, think of the Batman, think of the balletic spins and kicks, the terrible punches, the bodies in motion.

There’s nothing sinister about this, no more than there’s anything original: it’s merely the difference in artistic technologies employed. One’s hand fitting itself to one’s tools. With prose, all you have are words, and the reader’s sensorium, and the changes and echoes you can ring by banging the one against the other: and so for effect you’re going to focus on making the reader feel (and see, yes, and hear and smell and taste, too) what’s happening. You’re going to do to them, and if you’ve got a protagonist in the way, you’re going to do it through them. —Whereas with comics you’re handing the reader what they’re seeing (with certain shorthands and gestures and signs and symbols to be interpreted according to various rules, yes, we’re still reading, after all); it’s pretty much the preoccupation with what it is you’re doing, and doing just looks ever so much cooler than being done to. And so.

And of course there’s all sorts of spoiling overlaps, and yes Wolverine is the best there is at soaking up yadda yadda, and Bond is himself a sadistic bastard, but then he’s also in the movies a lot. —This is hardly a hard and fast genre rule unwritten or otherwise; it’s hardly an idiomatic necessity. It’s a reflexive tendancy. It’s a pattern, in search of a theory, wondering whether there’s a problem with reflexively, unthinkingly, turning to doing, or being done to, in order to drag the reader from the phenomenal to the sublime. Probably not. (One so dislikes being judgmental.) But like I say, it hasn’t gone away. Give it a poke. See if something happens.

Happy Delany Day.

With a poem, Ray Davis reminds us of the other reason for the season. (“ATTN Will Smith’s agent: The Motion of Light in Water is the EPIC SAGA of a GENERATION shown via the TRUE STORY of a GENIUS who TRIUMPHANTLY OVERCOMES a NERVOUS BREAKDOWN!”)

Hitchcock, dropping Jupiter.

I never did come close to figuring out what I was talking about last year, did I. (1; 2; some context; 3; elsewhere; some further context; 4; intermission.) —Maybe if I’d seen Rear Window recently, I’d have put it better. Maybe not.

This is Sparta.

I’ve only got the one recording of the Mountain Goats’ “Black Molly.” It’s from Bitter Melon Farm. He’s singing in some dive bar somewhere, you realize, hearing crowd noise bubbling under the tape hiss. The sound of the guitar chords is degraded enough that they slash and ring like bells, and he’s belting out the lyrics in that adenoidal whine he saves for the angry songs, the one that’s either powerful, or the reason you don’t listen much to the Mountain Goats—

black mollies in the aquarium,

darting back and forth as though an earthquake were certain

and I turned up the heater

and I ripped off my shirt

and I grabbed hold of my stereo

and I threw it out the window

you were in town

again

—and this is the chorus; he’s stretching that word “town” out past any normal limit—

you’d come around

again

—and again, with “around,” and you can hear what he’s doing to his voice, punishing it with this song, and I know why half the time when I’ve seen him live, and why on most of the bootlegs I’ve got lying around on my harddrive he usually stops somewhere in the set and says if he goes on, if he sings “Going to Georgia” or “No Children” the way the crowd wants, he’s not going to have any voice left for tomorrow, in Eugene or Olympia or San Francisco.

you were dragging me down again with you

“Fuck Eugene!” somebody usually says. And sometimes he sings what the crowd wants. Sometimes he doesn’t. The crowds have been getting pushier, lately. And larger. But this time nobody’s calling for anything, because he’s still singing “Black Molly”—

siamese fish flashing like sparklers

it started to rain

and the telephone rang a couple of times

I put a bullet through its cold dead brain

and I got out my photographs of you

and I put bullets though all of them too

you were

—and here, in this recording, the crowd noise boils over in cheers and whoops, applause even, as he lifts and pulls his voice to some triumphantly broken point—

in town

again

you’d come around

again

you were dragging me down again with you

yeah

And maybe it’s the release in his voice they’re cheering? That sudden savage joy that fills you when you finally give up and stop worrying and fall into the fact that you’re going down? That you know, you finally know there’s nothing you can do?

I’d like to think so. But somebody starts the cheer with the bullets, the ones that go through every photograph of her he’s got.

Heidi posted a mashup poster for The 40-Year-Old Spartan, and I chuckled and followed the link and there were enough other goofy mashups there that I emailed it on to a couple of friends who’re the sort to chuckle at that sort of thing. LOLSpartans. You know. And I didn’t think anything more of it until one of them emailed me back. “Those images are really great,” she said, “but those message board quotes, though probably hyperbolic, give me the serious wiggins.”

Message board quotes?

Sure, there was text, but I hadn’t read it. I’d assumed it was just there to frame the funny pictures. Who has time for that? —So I went back to the site. “To say that you’d have to be living under a rock to not know about all the hype surrounding 300 would be an enormous understatement,” it begins.

The movie’s hype has taken on absolutely absurd proportions, to the extent that it just had to be documented on WTFsrsly…

On forums you find posts about crazy 300-related stories such as this one by SmithX on the IGN boards:

And it ends like this—

The hype has turned into madness! (I’m refraining from making a “madness” joke here) The past month there have been many threads (some that had nothing to do with the movie) that randomly derailed into posts screaming “THIS IS SPAARTHAAA!”. Meanwhile, people are hard at work doing these hilarious 300 photo manips:

And then the mashups. But the message board quotes? The crazy 300-related stories posted to demonstrate that the hype’s absolutely absurd?

Here’s the first one:

Well i found out someone i know is in alot of trouble today, he was drunk in a club and there was a girl dancing by some stairs so he went up to her…..................... Kicked her down the stairs shouting this is SPARTA

Here’s the second:

We had all lined up in front of the theater for about 30 minutes, and then they brought us in. I had to stand right beside these two fat, horse-faced lesbians eating each other tongues like they were making a political statement or something. So, like 30 minutes later, we end up shuffling in the theater and these bitches start bitching about having to wait when the movie is about to start and it turns out they were going to see that Jim Carrey movie 23 and they were missing it. So, the ugliest of the two just exclaims like there’s nobody there “This is the wrong fucking movie!”. I just had to do what I did next. I shouted at the top of my lungs “This is SPARTA” and kicked her in the chest, causing her to fall down about 8 steps to the floor. Most were shocked but about 80% of the theater started to cheer as I was forcibly thrown out by 2 officers. Charges are going to be pressed against me apparently, but it was worth it.

And that’s it; those are your examples of crazy 300-related stories that demonstrate the hype has taken on absolutely absurd proportions. —Are they true?

Does it matter?

I don’t know if John Darnielle sings “Black Molly” live all that often. Is it an old favorite now mostly retired from the setlist? (He’s sick to death of “Going to Georgia,” and you can’t really blame him.) An old obscurity, dredged up now and again for the fans who’ve been with him since the cassette days? I don’t know. I’ve seen the Mountain Goats a number of times, and he only ever did “Black Molly” once. Was it the last time we saw him at the Doug Fir? Or the time before that? I’m not sure. Did somebody specifically ask for “Black Molly”? I don’t remember. But I do remember how he sang it. —The other thing I remember from that show, that sticks clearly in my head, is how he sang “Game Shows Touch Our Lives,” his voice lifting a little from the hushed falsetto he saves for the reflective songs, “People say friends don’t destroy one another,” and then Peter joined him and they punched the next line, “What do they know about friends?” the way he punches “Hand in unlovable hand” when he sings “No Children” or “Take your foot off of the brake, for Christ’s sake” when he sings “Dilaudid,” except really that’s more of a strangled yelp, isn’t it. —Damaged people damaging each other. The savage joy that fills you when you let go. Apocalyptic. “Black Molly” begins like that.

“Black Molly” began like that, yeah, there in the dark crammed basement of the Doug Fir, but it started at a yelp and climbed from there, and the crowd all around was starting to grin when he threw the stereo out the window, and there was a whoop when he stretched that first “town” out on a rack, but it was only one whoop. And then the phone rang a couple of times, and he shot it, and then he pulled out the photographs, and there were more whoops, and he put bullets through all of them too, and the crowd started cheering and applauding, just like it does on the Bitter Melon version I’ve got, well before the song is over, yeah!

Why?

I’d like to say it’s the savage joy. It’s the release. You’re coming around again, to drag me down again, and there’s a certain exhilaration in giving up to that, the top of the emotional rollercoaster thrill. —But I could just make out their faces in the dark and even if I couldn’t I could hear it in their voices. The crowd was cheering the rage, however impotently expressed. The crowd wanted the bullets, and the bullet holes in the photographs, and. The crowd smelled blood. —And I know why he’s angry, but it’s not why they’re cheering, and I was left standing there, outside the concert, outside the song, my stomach cold, thinking of screwflies.

And this also has been one of the dark places of the earth.

“Tragic futility, though, has a hard time lodging in the imagination of boys in short trousers.” —Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory

SWM ISO DFK, GFE.

I realize it’s terribly judgmental and tools-and-house of me, but I can’t help pointing to this lithe little anecdote as a neat summation of why it is at the end of the day I shake my head at the very idea of “difference feminism.” (—“Deep French kissing,” by the way.)