Failsons & November criminals.

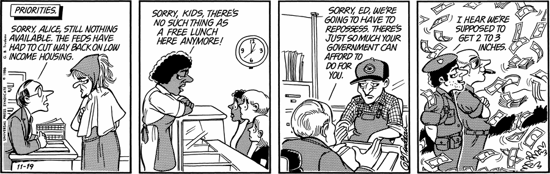

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay! It’s the thirty-fourth anniversary of my radicalization, which I can date with such alacritous precision due quite simply to the fact that it in turn is due to a comicstrip:

It was more of a straw and a camel’s back than a short sharp apocalypse: and it’s not like there wasn’t then or isn’t even yet a long ways left to go (not too much later, I found myself at Oberlin, tut-tutting my fellow students’ embrace of John Brown, whom I, ’Bama boy that I am, took, at the time, to be a righteous but nonetheless terrorist)—but, but: I’d wet my feet in a Rubicon. We could’ve been making the world a better place. We chose not to.

Thinking about how much of what was then recent history I learned back in the day not from lectures and classwork, from school, but from nipping off to the library to dig through Doonesbury collections, augmented by archives of Feiffer and Herblock and, well, yes, MacNelly, one must have balance, one supposes.

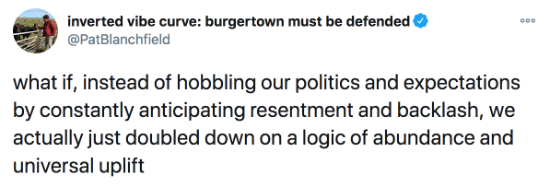

Thinking about that because of what Pat Blanchfield says in this snarkily “Bruckheimer shit” walkthrough of the latest instantiation of the (wildly popular) (wildly deranged) Call of Duty franchise—

A quarter of a billion people, whatever, have played these games, um, and so many American men do, one of the few ways a lot of people ever learn anything even resembling, like, the existence of this history, like, for example, like, in the last game, we were in Angola, is through these games.

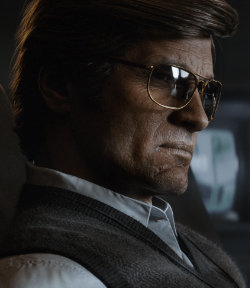

Sobering, and not just for the ideology the games are steeped in, Dolchstoßlegending this or that regrettably unpleasant incident from Yankee history into thrillingly deniable covert ops that left the world, our world, far better off than it otherwise could’ve been, and don’t you forget it— not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

not just the ideology, but also the technique: the hilariously toxic masculinity (when have you ever seen Robert Redford looking so ghoulishly rugged?), the conversational hooks and moral dilemmas drawn from grade-Z B-movie scripts (to say nothing of those meticulously recreated backlot backdrops), all the eye-snagging tics and dialects of body language drawn from deeply uncanny valleys, and touches like the robustly verbose commanding presence of President Dutch, who marches into an expository cutscene (after a prologuizing Gladio massacre) ahead of an anachronistic shaky cam—this isn’t the Reagan to be found in anything close to any actual history this world came up out of; this is a Reagan from a Saturday Night Live skit—

—(and also, yes, all the guns and the shooting and the extreme violence and all that stuff). —It’s, and I use the term advisedly, a cartoon: both in the sense that it’s deliberately, expressively, ruthlessly simplified, drawing power from its crudely broad strokes, and also in that it’s deliberately, ostensibly disposable: a work of paraliterature no one could ever take seriously, c’mon, a staggeringly elaborate, kayfabily po-faced act of kidding-on-the-square, a deniable covert op that leaves us thinking all unawares with precisely what it is we’ve been laughing at, for however long we’ve been twiddling our thumbs at the flatscreen.

Anyway. Down with all Commander Less-Than-Zeroes, wherever they might be found. Give me a November criminal any goddamn day.