God, hes left as on aur oun.

Manichæan.

I might’ve made a mistake when I began the thing-that-argues. —Because I could not hear myself constantly and on a regular basis referring to Jo as a white woman (or, God forbid, a White woman), it would not be fair to single out Christian, say, by referring to him as a Black kid, or to Gordon as a black man.

Because I would not mark all of them, I could not mark any of them, so as to mark them all the same. The logic’s ineluctable.

But, you know. Logic.

It’s not just a matter of black, or Black, and white, of course. —How would you go about marking Ellen Oh? Would you say she is Korean? Even though she was born in Alabama, and most of her family hasn’t lived in Korea for a couple generations now? (Can you specify to any useful degree the differences in appearance between all possible individuals whose forebears might at one point have been sustained by that mighty peninsula, and the appearances of anyone, everyone else, that would render such a marker immediately perceptible, and adequately useful?) —You might perhaps think “Asian” to be an acceptable compromise, as a marker, but look for God’s sake at a map: Asia’s everything east of the Bosporous. How staggeringly varied, the appearances of everyone from there, to there! Worse than no mark at all, distorting marker and marked, and to no good or necessary purpose.

(The Ronin Benkei was flatly Japanese, even though Farrell was much too polite ever to notice more than a few echoes of classical Japanese manners in the gestures of Julie Tanikawa, whom he never heard swear in Japanese, except that once, for all that she spoke it as a child, with her long-dead grandmother.) (And as for Brian Li Sung—oh, but comics have their own markers, at once far more persnicketily precise, and yet so roomily ambiguous, and I’ve said too much.)

It’s not that the characters aren’t marked at all, of course: just not with such totalizing, reductive, contingent signs. Everyone’s described in much the same manner: their clothing, the way they carry themselves, their hair, how they say the things they say, the way the light hits them (the visible world being merely their skin)—the hope, of course, being that these pointilist details will accrete into a portait in the reader’s mind—inaccurate, perhaps, at the start, but resolving over time toward something more and more like what’s intended. (—Or, to be precise, what’s needed to make what’s intended work; this is imprecise stuff, this work, but really, think about it: how could even a single person, that is so large, ever fit within a book that is so small?)

But what does such a cowardly refusal on the part of the narrative voice, to plainly mark what any other medium would’ve plainly marked, by virtue of not being limited to one word set after another—what does this do to a reader’s relationship with the portrait they’ve been assembling when it suddenly must drastically be rearranged, after thousands upon thousands of those words? (I mean this at least is gonna hit a bit different than Juan Rico offhandedly clocking himself in a mirror on page two hundred and fifty.)

But let’s turn it around a minute: is it my fault if you didn’t assume from the get-go that an un(obviously)-marked character in a novel written by a white man, in a rather terribly white idiom, set in one of the whitest cities in the country—is it on me if you’re the one who assumes, before you’ve been told, that this character’s clearly white?

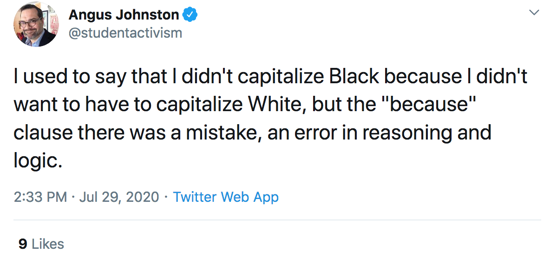

My own take on the question of the moment, or at least of the moment when I began sketching this out (though I’ve been thinking about something like it for a while now; it might’ve been the foreword of the third book, had anything coalesced in time)—my own take is not unlike what’s laid out by Angus above: because I would not dignify the constellation of revanchist grievances, the cop’s swagger and the supervisor’s sneer, that make up the bulk of what passes for the race I could call my own—because I would never capitalize that—well. Logic demands. Right?

But it’s ad fastidium, is what it is. —I could bolster it with an argumentum ad verecundiam, by turning to what Delany’s said, on his own perspective on the subject, bolstered in turn by Dr. DuBois’:

—the small “b” on “black” is a very significant letter, an attempt to ironize and de-transcendentalize the whole concept of race, to render it provisional and contingent, a significance that many young people today, white and black, who lackadaisically capitalize it, have lost track of—

Oh, but that was written in 1998, which is further away than it seems. Which is not to say anything’s changed, good Lord, I wouldn’t know, I only ever had breakfast the one time with the man, and we mostly talked about Fowles. But then, there’s this, from 2007, or 2016, depending:

“And those aren’t races. Those are adjectives of place—like Hispanic. And Chinese. Caucasians are people from the area in and around the Caucasus Mountains, which is where, at one time—erroneously—white people were assumed to have originated.”

“Latino..?”

“And that refers to the language spoken. So it gets a capital, like English and French. There is no country—or language—called black or white. Or yellow.”

But when he told this to a much younger, tenure-track colleague, the woman looked uncomfortable and said, “Well, more and more people are capitalizing ‘Black,’ these days.”

“But doesn’t it strike you as illiterate?” Arnold asked.

In her gray-green blouse, the young white woman shrugged as the elevator came—and three days later left an article by bell hooks in Arnold’s mailbox—which used “Black” throughout. He liked the article, but the uppercase “B” set Arnold’s teeth on edge.

And yes, it’s much the same argument! But it sits very differently, with different emphases and outcomes, when it comes from the mouth of Arnold Hawley, such a very fragile man—not Delany’s opposite, no: but still: his reflection, seen in a glass, darkly, as it were.

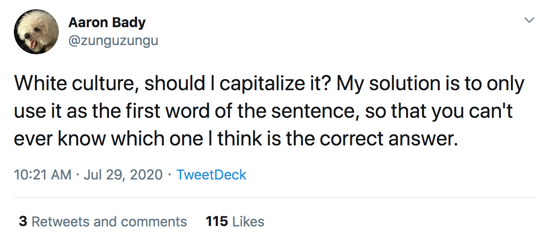

(Everyone knows there is no country called black, or language. What capitalizing the B presupposes is: maybe there is?)

But my own take on whether to capitalize “black” has no bearing on the thing-that-argues—in part because I’ve short-circuited it entirely, yes, but also and mostly because none of the people in it give a damn what I think, nor should they: the thing-that-argues, when it turns its attention to any such matter, should only ever care what it is they think, and how, and why: Christian thinks of himself as a Black man, for all that Gordon sees him as a black boy; H.D. sees herself as a Black businesswoman, concerned as she is with Black businesses; Udom, the new Dagger, still thinks of himself as from Across-the-River, though he knows most everyone these days sees him as one of the Igbo; Zeina, the new Mooncalfe, would probably say she’s black, or crack a bleak joke about Atlantis, and drowned mothers-to-be, or maybe she’d punch you, I don’t know; and Frances Upchurch (though that is not her name) would tell you exactly what you’d think she would, and never you’d know otherwise. —And each of them must be able to believe what they believe, to fight for it, or change their minds, without ever having to worry about some quasi-objective narrative voice thinks maybe it knows better blundering up to flatly gainsay them, this white voice in a terribly white idiom telling each and every reader that this was said by a Black man, or that was thought by a black woman, tricking these readers, every one, into thinking they maybe know what the author thinks—or worse, what the thing-that-argues thinks—and thus, what ought to be right, and further thus, who should be, could be, must be wrong. —And this understanding extends to all things.

(The narrative voice of Dark Reflections does not capitalize “black,” when referring to jeans, or to people, and so we can think we know what the author thought just a few years ago, or at least his copyeditor.)

So maybe I made a mistake at the start of it all. But there was thought behind it? At the start? Reasons to have done it, not that those are a guarantee of any God damn thing. —Maybe I’d do it differently, I were setting out today. Maybe I still regret using quotations marks, or writing it down as “Mr.” instead of “Mister.” But here we are.

There is a strength in writing as a fool, you do it right. Talking outside the glass. The room, that negative space affords, for the characters, for the story, for the readers (or so I tell myself, but I am a fool)—there’s power, in setting a taboo like this. You may not talk inside the glass, but still: you spill enough words, the shape of the glass can start to be made out.