Tripping the light.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” says the man, and, okay? I guess? I mean, I dream in English, and I’d bet he does, too, mostly, but I don’t think he means the best fantasy is written in English, I think he means the best fantasy is written in the language you grew up with, that you know in your bones, because that’s where the tricks work best: your feet think they know the stones of this path, and follow them without thinking; a clever gardener can then lay them to lead them all-unaware through shadowy copses by undrunk brooks to sudden breathtaking impossible vistas that couldn’t, shouldn’t be where they seem—and yet—

All the farm was shining with the hideous unknown blend of colour; trees, buildings, and even such grass and herbage as had not been wholly changed to lethal grey brittleness. The boughs were all straining skyward, tipped with tongues of foul flame, and lambent tricklings of the same monstrous fire were creeping about the ridgepoles of the house, barn, and sheds. It was a scene from a vision of Fuseli, and over all the rest reigned that riot of luminous amorphousness, that alien and undimensioned rainbow of cryptic poison from the well—seething, feeling, lapping, reaching, scintillating, straining, and malignly bubbling in its cosmic and unrecognisable chromaticism.

William Dean Howells wrote ten horror stories between 1902 and 1907. The stories are not highly regarded by most critics of horror; a typical comment is S.T. Joshi’s sneer that “the element of terror, or even the supernatural, in these stories, is so attenuated… that the overall effect is a kind of pale-pink weirdness entirely in keeping with the era in which they were written.”

We read fantasy to find the colors again, I think.

“The best fantasy is written in the language of dreams,” he tells us, but it turns out he’s more concerned with imminence, and evanescence, something “more real than real” that only lasts for one “long magic moment before we wake.” —And, I mean, okay, I don’t know about you, but as for me, I barely remember my dreams; I wake up knowing I have dreamed, but mostly I’m left with a (yes) color, a tone, a vector or at least a sense of motion, scraps that dissolve even as I try to pin them down, and there’s something in that grasping-after, that sense of having lost what I never knew I’d had, that gets at something in fantasy, sure, but—

“Fantasy is silver and scarlet,” he says, “indigo and azure, obsidian veined with gold and lapis lazuli,” and here I’m brought up short—is that it? Why stop here? “Obsidian veined with gold,” I mean, you can find that in the bathroom of a Trump hotel. You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling:

She spoke, and the first low beams of the sun smote javelin-like through the eastern windows, and the freshness of morning breathed and shimmered in that lofty chamber, chasing the blue and dusky shades of departed night to the corners and recesses, and to the rafters of the vaulted roof. Surely no potentate of earth, not Crœsus, not the great King, not Minos in his royal palace in Crete, not all the Pharaohs, not Queen Semiramis, nor all the Kings of Babylon and Nineveh had ever a throne room to compare in glory with that high presence chamber of the lords of Demonland. Its walls and pillars were of snow-white marble, every vein whereof was set with small gems: rubies, corals, garnets, and pink topaz. Seven pillars on either side bore up the shadowy vault of the roof; the roof-tree and the beams were of gold, curiously carved, the roof itself of mother-of-pearl. A side aisle ran behind each row of pillars, and seven paintings on the western side faced seven spacious windows on the east. At the end of the hall upon a dais stood three high seats, the arms of each composed of two hippogriffs wrought in gold, with wings spread, and the legs of the seats the legs of the hippogriffs; but the body of each high seat was a single jewel of monstrous size: the left-hand seat a black opal, asparkle with steel-blue fire, the next a fire-opal, as it were a burning coal, the third seat an alexandrite, purple like wine by night but deep sea-green by day. Ten more pillars stood in semicircle behind the high seats, bearing up above them and the dais a canopy of gold. The benches that ran from end to end of the lofty chamber were of cedar, inlaid with coral and ivory, and so were the tables that stood before the benches. The floor of the chamber was tessellated, of marble and green tourmaline, and on every square of tourmaline was carven the image of a fish: as the dolphin, the conger, the cat-fish, the salmon, the tunny, the squid, and other wonders of the deep. Hangings of tapestry were behind the high seats, worked with flowers, snake’s-head, snapdragon, dragon-mouth, and their kind; and on the dado below the windows were sculptures of birds and beasts and creeping things.

“Fantasy tastes of habaneros and honey, cinnamon and cloves, rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer,” and now I can only sigh: we were talking again just a couple of weeks ago about how flavor’s the very essence of a sylph, and to mistake the flavor for its ingredients is one of those, whaddayacall ’em, category errors; to set “rare red meat and wines as sweet as summer” as our sylphs against the (by implication) drab reality of “beans and tofu” is to not only lose the vegetarians in the audience, or those who’d quail before a cellar full of nothing but sweet wine: it loses that astounding little plate of hiyayakko we had in that strip-mall sushi joint in North Carolina, just a chilly silky geometrically perfect cube of tofu topped with flakes of ginger and slivers of scallion and tendrils of bonito and oh, that one first perfect bite, and it loses what you can make with a bag of dried black beans and a couple of cloves of garlic and salt and pepper and a cup of plonk and some water and laughter and time. —It’s precisely the same error that tells us fantasy’s only to be found in Minas Tirith or Gormenghast or Camelot, and never in plywood or plastic or (yes) strip malls. It’s to mistake the gesture for the deed, confusing the things the wonder-generating mechanisms have been attached to with the wonder-generating mechanisms themselves—my God, if you can’t conjure with a name like “Burbank,” or “Cleveland,” you’ve no business being in this business. —Multi-million–dollar empires aside.

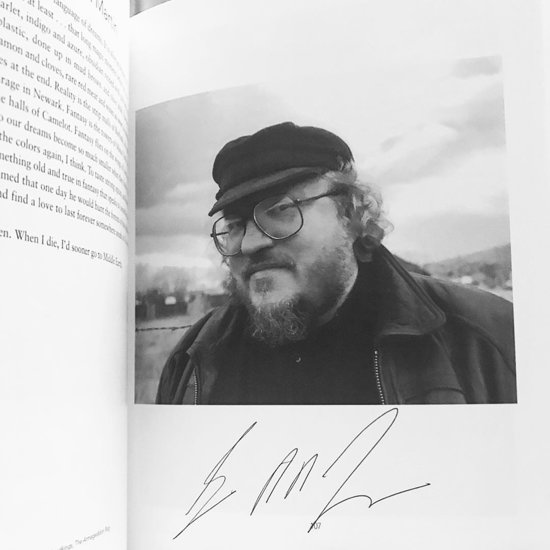

And I know, I know: this passage is flavor text from an album intended to be carted about at conventions, collecting autographs; it was written a quarter-century ago, long before Martin’s fantasy ate the world, or at least HBO; well before the fuck-you money, which maybe helps to explain why his images of fantasy are so luxurious, drawn from Harry & David and Conran, set against beans and rice. (Oh, but that’s uncharitable, coming from me with my Japanese appetizers and cellars of peppery wines and those tricksily landscaped gardens there, up at the top.) —It’s old, and it’s slight, this passage, it’s silly, sure, but it keeps coming back—

—and silly or slight or old as it is, one of the most important lessons fantasy has to teach us is that you are what you pretend to be. The gesture may not be the deed, but performing the gesture is itself a deed, and if you keep telling us fantasy’s written in the language of dreams, that it fulfills wishes, that it gives you the tastes you yearn for and the colors you want to find again, it’s gonna raise a lot of terribly pointed questions when the fantasy you’re most known for, the deed your gesture performs, the work you put into the world is so very full of white folks and rape. —There’s something else going on here, something more, and to paper it over with something so silly and so slight is to turn those words to ash with the slightest consideration.

(“They can keep their heaven,” he says; “When I die, I’d sooner go to Middle-earth,” and, I mean, I’ve been to the Shire? Like, actually been there? Drove out on a whim fourteen years ago, when our car was new. —Whole place went under just a bit later, in the Crash of ’08.)