With thanks to Liz Wallace.

The crew is unisex and all parts are interchangeable for men or women.

—Dan O’Bannon, Alien (née Starbeast)

FOOM! FOOM! FOOM! With explosions of escaping gas, the lids on the freezers pop open. —Slowly, groggily, six nude men sit up.

Having pretty women as the main characters was a real cliché of horror movies and I wanted to stay away from that. So I made up the character of Ripley, whom I didn’t know was going to be a woman at the time… I sent the people of the studios some notations and what I thought should happen and when we were about to make the movie the producer of the film jumped on it. He just liked the idea and told me we should make that Ripley character a woman. I thought that the captain would have been an old woman and the Ripley character a young man, that would have been interesting. But he said, “No, let’s make the hero a woman.”

—Dan O’Bannon, Cult People

[Veronica Cartwright] originally read for the role of Ripley, and was not informed that she had instead been cast as Lambert until she arrived in London for wardrobe. She disliked the character’s emotional weakness, but nevertheless accepted the role: “They convinced me that I was the audience’s fears; I was a reflection of what the audience is feeling.”

—Wikipedia, “Alien (film)#Casting”

FANTASTIC FILMS

Have you had any second thoughts about doing science fiction pictures in a row – first, Invasion of the Body Snatchers and now Alien?

CARTWRIGHT

Oh yeah. They were both screaming and running and crying films. But they were both very different.

FF

Are you worried being type-cast in the sort of role?

CARTWRIGHT

Well, I have to be very careful in picking my roles. I would like to do something comic next. I’m tired of crying. You know what I mean.

—Fantastic Films interview with Veronica Cartwright

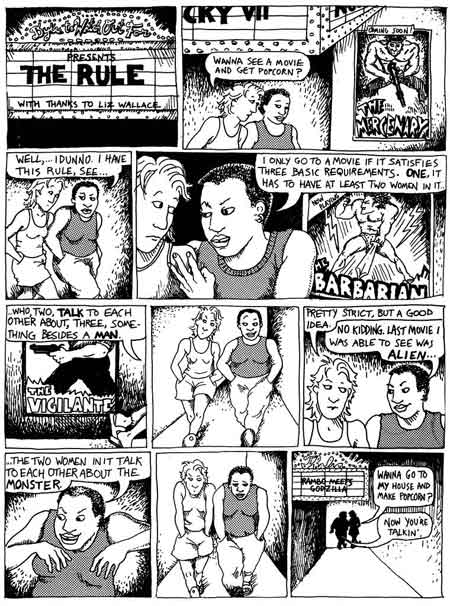

What’s the Mo Movie Measure, you ask? It’s an idea from Alison Bechdel’s brilliant comic strip, Dykes to Watch Out For. The character “Mo” explains that she only watches movies in which:

- there are at least two named female characters, who

- talk to each other about

- something other than a man.

It’s appalling how few movies can pass the Mo Movie Measure.

Julie from Portland, OR, kindly emailed us to let us know that lefty blogs like Pandagon have been discussing the Mo Movie Measure a film-going concept that originated in an early DTWOF strip, circa 1985. We were excited to hear that someone still remembers this 20-year-old chestnut. But alas, the principle is misnamed. It appears in “The Rule,” a strip found on page 22 of the original DTWOF collection. Mo actually doesn’t appear in DTWOF until two years later. Her first strip can be found half-way through More DTWOF. Alison would also like to add that she can’t claim credit for the actual “rule.” She stole it from a friend, Liz Wallace, whose name is on the marquee in the comic strip.

—Cathy, not Alison, despite what the author tag says

By the way, when I coined the phrase “Mo Movie Measure,” I screwed up—the character in Dykes To Watch Out For who says it, isn’t Mo!

She bears a strong resemblance to Ginger, but it isn’t a definitive resemblance. The strip is from before DTWOF developed an ongoing cast of characters, so it is hard to tell if Bechdel intended Ginger to have been that character from that strip when Ginger started appeared in the strip. The character in “The Rule” seems physically bulkier than I recall Ginger being, but that could be a shift in drawing style.

Also, the bit about the two female characters having to have names—which I thought had been in the original comic strip—was apparently added by me. Oops again.

That’s how these cultural ideas develop—it’s just a giant game of “telephone.”

The Mo Movie Measure—what to call it now?

/bech•del test/ n.

- It has to have at least two women in it

- Who talk to each other

- About something besides a man

A variant of the test, in which the two women must additionally be named characters, is also called the Mo Movie Measure.

—Wikipedia, “Dykes to Watch Out For#Bechdel_test”

If any studio executives are reading this, let me give some examples: Names are things like “Annie Hall” and “Erin Brockovich” and “Scarlett O’Hara.” Things that are not names include, to cite some credits from this year’s movies, “Female Junkie,” “Mr. Anderson’s Secretary,” and “Topless Party Girl.”

The wonderful and tragic thing about the Bechdel Test is not, as you’ve doubtless already guessed, that so few Hollywood films manage to pass, but that the standard it creates is so pathetically minimal—the equivalent of those first 200 points we’re all told we got on the SATs just for filling out our names. Yet as the test has proved time and again, when it comes to the depiction of women in studio movies, no matter how low you set the bar, dozens of films will still trip over it and then insist with aggrieved self-righteousness that the bar never should have been there in the first place and that surely you’re not talking about quotas.

Well, yes, you big, dumb, expensive “based on a graphic novel” doofus of a major motion picture: I am talking about quotas. A quota of two whole women and one whole conversation that doesn’t include the line “I saw him first!”

—Mark Harris, “I Am Woman. Hear Me… Please!”

I was struck by the simplicity of this test and by its patent validity as a measure of gender bias. As I thought about it some more, it occurred to me how few of the classic works of literature that I teach to my high school freshmen would pass this test: The Odyssey? Nope. The Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass? Nope. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Nope. Romeo and Juliet. Nope.

What’s wrong with me?

—Frank Kovarik, “Navigating the waters of our biased culture”

Female characters are traditionally peripheral to male ones. That’s why we don’t want to hear them chatting about anything other than the male characters: because in making them peripheral, the writer has assured the women can’t possibly contribute to the story unless they’re telling us something about the men who drive the plot. That is the problem the test is highlighting. And that’s why shoehorning an awkward scene in which two named female characters discuss the price of tea in South Africa while the male characters are off saving the world will only hang a lantern on how powerfully you’ve sidelined your female characters for no reason other than sexism, conscious or otherwise.

—Jennifer Kessler, “The Bechdel Test: It’s not about passing”

Bechdel-Wallace test or Delany-Hacker criterion: http://thisislikesogay.blogspot.com/2009/10/rule.html