God, hes left as on aur oun.

Hope is the new bleak.

Every now and then

A madman’s bound to come along.

Doesn’t stop the story—

Story’s pretty strong.

Doesn’t change the song.

While back, Kugelmass wrote about an “indispensable essay” by Sean McCann and Michael Szalay called “Do You Believe in Magic?”—and while I haven’t gotten around yet to reading it myself, this passage of Kugelmass’ stuck with me:

While McCann and Szalay criticize academics who believe in the political efficacy of their symbolic labors, I would argue that most scholars working on culture now invoke “the political” in bad faith, with little hope of creating real change, out of a desire to seem compassionate and politically involved to hiring committees and their peers. The proof is in the pessimism: the message is that political change is impossible, even if an awareness of injustice is still praiseworthy.

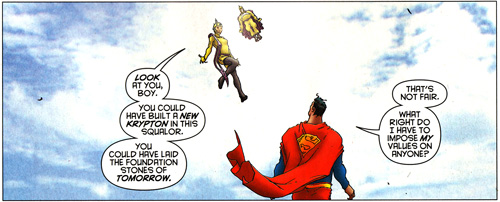

Mostly because it reminded me of nothing so much as this:

That’s from Runaways, which is about the best set of characters to be added to the Marvel universe in thirty years—and I can say that not because it’s a good comic book about compelling characters, but because so few new characters are ever added to anything like a Marvel universe (instead, we work endless shifts in the nostalgia mines, coming back to the past a bully again and again to eat our own four-color fictions, yes yes). —The Marvel universe centers around a New York City riddled with superheroes, from the Avengers up on Fifth to the Fantastic Four in midtown to the X-Men out in Westchester; Brian K. Vaughn drops us instead in Los Angeles, where a group of kids discovers their parents are actually supervillains, working together to control the city and its crime. (Vaughn uses the Gothamite myopia of 417 5th Avenue to good effect: the reason LA’s been so quiet in the 616, home until now to nothing more superheroic than the West Coast Avengers and Wonder Man, is that these supervillans are so damn good at what they do: their fist is adamantium; its grip implacable.) —The kids, of course, do what anyone would do, upon discovering their parents are evil: they run away from home, learn to use their powers and gifts, and come back to fight the good fight, defeat their parents, and—homeless, jobless, hunted—squat in a cave under the La Brea Tar Pits, using their powers and gifts to, y’know, fight supercrime and stuff. (And help other runaways, of course, like the android son of Ultron, or the Super-Skrull above, who’s run away from penn’s people’s genocidal war.)

That is, of course, what you call high concept, and to my mind works much better than Vaughn’s other, better-known comic-book pitch.

After all, what heroes these kids are! Homeless, jobless, hunted, still: they don’t try to change the world about them. Much as they might want to. They use their powers and gifts, their superstrength and supertech and supermagic and their telepathic velociraptor instead for good, to keep the world about them safe as it is. —An awareness of injustice is all well and good, you see. But political change is impossible. Only villains try to change the world.

This is how it works in the superhero business, of course; the story that’s pretty strong. —And in part it’s commercial necessity, sure: superheroes live in something very much like our world, except with superpeople, and they have to come back month after month for another 22 pages of four-color adventure; if they went about trying to change the world, well: pretty soon their world wouldn’t look very much like our world, would it? What with all those superpeople in it, with all that great power.

But it’s also what’s bred in the superhero’s bones: that great power lies hidden until some threat springs up—and then the glasses come off, the shirt’s ripped open, the power’s unleashed. Once the threat’s vanquished, the power retreats; our hero’s alter ego stands up, brushes away some debris, resettles the glasses, and no one’s ever the wiser that they were saved by the great cloaked power that walks among them every day. —If you start to use that power not just to save the world from threats but to change it, make it better—well. You’d be out there all the time. You’d never wear the glasses again. They’d start to catch on.

A great responsibility comes with that great power, after all, to do the right thing. But what is the right thing? (You think you know? Really? Who are you, God?) —Best to swear your own Hippocratic Oath before pulling on the longjohns: First, make no change. “Because traditional superhero teams always put the flag back on top of the White House, don’t they?” said Grant Morrison back in the year 2000. They were writing an introduction to the first collection of Ellis and Hitch’s Authority. “They always dust down the statues and repair the highways and everything ends up just the way it was before…”

Morrison would have you believe (for the length of the intro, anyway) that Ellis and Hitch invented the idea of uncompromising superheroes who set out to change the world like the best of proper villains: “The Authority dares to imagine a world beyond the post-modern ironic hopelessness of endless recycled TV quotes and retro-nostalgic feedback. Welcome to a superteam with an agenda, on a scale beyond the billion-dollar budgets. A superteam whose headquarters looks like a dog’s nose and still kicks ass.” —It’s bollocks, of course, and only forgivable because Morrison clearly knows it’s bollocks. Superheroes have in one way or another been bucking against this static stricture for years, ever since the writers and artists and editors started to suss out that, y’know, they had this great power, right? Maybe a great responsibility went along with it?

They’ve been bucking at it, but they haven’t overturned it. The story’s pretty strong. Heroes defend the status quo. It’s what they do; it’s what makes them heroes. The Authority, who do not, end up as despotic demigods (with much less grace than Miracleman before them), and even from the start it isn’t so much a superhero comic as it is a noisy widescreen smashemup comic. —A much better high concept from Ellis is Planetary, where a villainous Fantastic Four defend a status quo that hoards the wonders promised by pulp fiction, keeping them out of the hands of the rest of us all; the righteous rage of the protagonists as they set about the task of returning our birthright is a splendid little engine of subversion. (Even better is his Global Frequency, in which cast-off Cold Warriors cobble together a DIY network of cellphones and satellites and Q-clearance secrets: mad scientists and retired superspies walking among us, keeping us safe from the pocket armageddim they helped to build back in the day for bosses who no longer have the budgets to keep them in check. Great cloaked power with a crippling responsibility fighting horrific threats—but threats to a hopeful new status quo, threats engendered by the overturned vestiges of the last status quo, still kicking out there in the dark.)

—Awareness of injustice is praiseworthy. Hell, it’s necessary: how else are you going to know whom to hit?

But political change: that’s impossible.

Turn back to that scene from Runaways, and that Kugelmass post:

The rainbow-colored girl is Karolina, who goes by Lucy in the Sky; she’s an alien whose parents hid in LA as movie stars and used their alien abilities to get ahead in the Pride. The one doing the fade from Jay-Z to Beyoncé is Xavin, the aforementioned Super-Skrull. —Xavin shows up after the Runaways defeat their evil parents and claims Karolina as his bride. The usual punchemup is followed by the usual expository dump: a long-ago agreement between their parents arranged a marriage between them, Xavin’s here to make good on it, and stop a terrible war between their peoples. But! Karolina’s gay.

“I… I like girls,” she says, outing herself for the first time to most of her team.

“Is that all that’s stopping you?” says Xavin. “Karolina, Skrulls are shapeshifters.” (It’s true. They are, and penn promptly shifts from Beast to Beauty.) “For us, changing gender… is no different than changing hair color.”

—Xavin has since spent most of the rest of the comic in male form, and while there’s tonnes of interesting possibilities there, ways to address sexuality and appearance and transgender issues, the reality is we’re dealing with the midlevel properties of a company that’s just now getting used to the idea of admitting the very existence of gays and lesbians in their proprietary, persistent, large-scale popular fiction. What we’re dealing with is a token gay character in a relationship that to every external indication is perfectly heteronormative. —Runaways is about to get a new creative team; “Xavin won’t be a girl skrull,” the artist has said; “editorial make a note on that already, that one will change completely.”

Some critical theorists try to avoid sounding corny or naïve by exiling their political optimism to a purely theoretical or ineffable realm, a move McCann and Szalay lampoon as “The art of the impossible.” To take one example, in uncomplicatedly’s excellent new post there is a description of the queer theory version of this:

This was particularly true of the queer theorists, at least two of whom focused on queer reading practice as something that draws on textual possibilities rather than textual actualities to move toward an imagined utopian future that is acknowledged as imagined, and yet still must be imagined.

Well, Christ. I mean really. Can you blame them?

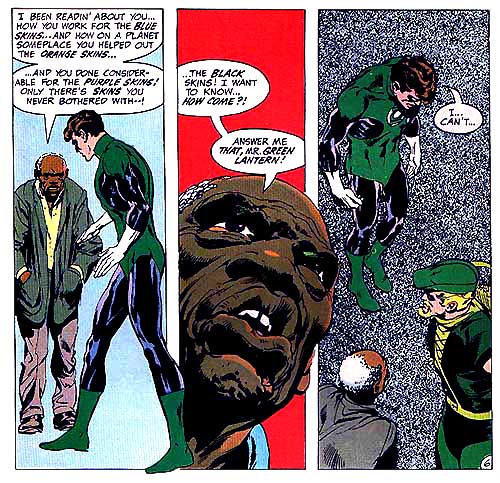

But to circle around again to whatever I thought my point was going to be when I got started (and I still haven’t put in anything about fear of power as political change is impossible so therefore the power to effect it must be impossibly great and the accompanying responsibility too too much to bear please take it from me please, and we could even hare off after learned helplessness if we wanted to: all the things that keep our superheroes reactive, stammeringly inadequate in the face of simple, pointed questions from those on the short end of the stick: status quo)—

Dr. Horrible, of course. Who’s talking about anything else? —“Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog” is Joss Whedon’s barn-raising internet show, a musical about a bumbling supervillain who’s trying to win the girl of his dreams from a smugly thuggish superhero. The supervillain is, of course, the protagonist, and so must win our sympathies; right at the very beginning of his first blog, he speaks a little speech to let us know what kind of supervillain he is:

And by the way, it’s not about making money, it’s about taking money. Destroying the status quo. Because the status is not quo. The world is a mess, and I just need to rule it.

He’s holding a plastic bag filled with the remains of the gold bar he tried to teleport out of a bank vault. “Smells like cumin,” he says, and sets it to one side—bumbling, like we said—but our hearts are with him. The world is a mess. We do not want the status quo. The smugly entitled heroes who defend it are not on our side.

We are all supervillains, now.

(Actually, our hearts are with him from his opening laugh, but that doesn’t help my argument. So.)

—This, by the way, is the secret of IOKIYAR; this is how it is that a Republican can shred the Fourth Amendment by resuming the warrantless wiretaps of yore, take up the Nixonian argument that it’s not illegal if the president does it, and blithely overturn the Magna Carta itself, and hear nothing but applause—yet if a Democrat but mentions a “civilian national security force,” the applause turns to jeers of brownshirts. —Republicans are conservatives; conservatives defend the status quo, standing athwart history yelling “Stop!” at every threat that comes along; those who defend the status quo are heroes—says so on the label. And we will always cut heroes more slack than villains.

(We are villains. We want to change the world. We demand, for instance, that we must all work together to change our collective behavior to offset the upset of global warming. —And it’s villains who demand we change the world; villains who demand we work together are fascists. QED.)

So we can’t change the world, political change is impossible, but we can change the story, right? A little? Change if not the status quo, then change the direction that phrase is pointing? And once we do that—

Well, yes, and no. You have to know where it’s pointing, first. “Dr. Horrible’s” isn’t a story about changing the world. That’s just a gesture towards audience sympathy which proves mildly interesting in the current political climate. “Dr. Horrible’s” is a story about a bumbling supervillain who’s trying to win the girl of his dreams from a smugly thuggish superhero. Dr. Horrible isn’t a world-shaking agent of change, out to slyly subvert our received sense of right and wrong; he’s upset that this girl he likes but can’t talk to is sleeping with this utter jerk who will never treat her right—

Dr. Horrible is a Nice Guy.™

For me, the most chilling moment in the whole thing comes at the beginning of Act II, during the duet between Horrible and Penny (the only person who does a damn thing to effect any political change at all)—it’s when Dr. Horrible, spying on a date between Penny and Captain Hammer, sings:

Anyone with half a brain

Could spend their whole life howling in pain

’Cause the dark is everywhere

And Penny doesn’t seem to care

That soon the dark in me is all that will remain

—Jesus, I thought. Does Whedon know what he’s playing with, here? The moment passes under Penny’s wispily soaring lines about how happy she is, how can she trust her eyes—does he see how twisted the responsibility just got in that seemingly tossed-off stanza, the status quo that’s been set up? —Yes. Yes, he does, and in the end, as Dr. Horrible takes his wrongful place in the Evil League of Evil, a bumbler no more, his only saving grace, his sliver of a chance at redemption, is he can finally see it, too.

Awareness of injustice is praiseworthy. Political change? Impossible. We can’t possibly change the world. Not without changing the story, first.

And if you’re going to do that, you’d damn well better be sure just what story it is you’re in.

Now, as to Reading Comics—

It’s finally dawned on me why Ellis made the Fantastic Four the villains of Planetary. A lot of the pulp heroes of the past did try to change the world and make it a better place. Before the FF, comic book heroes didn’t need to change the world because they were fantasy entertainment. They didn’t exist in the real world. They lived in Metropolis, Gotham City, Central City or some other made up place. By placing the Marvel Universe in the “real” world and by giving the characters real problems Stan started to break the fantasy. Once there are characters in the real world who have the ability to improve it, and don’t, those characters start to look awfully selfish. Ruling the world isn’t the only way to change it. The FF is supposedly rich from all of Reed’s patents but the Marvel Earth looks like our Earth. So apparently Reed is being paid not to share his miraculous inventions. And he’s okay with that.