God, hes left as on aur oun.

Don’t dream it, be it.

I don’t know how Kazu pulled it off: somehow, he got hold of Scott McCloud’s comics retrospective from 2054.

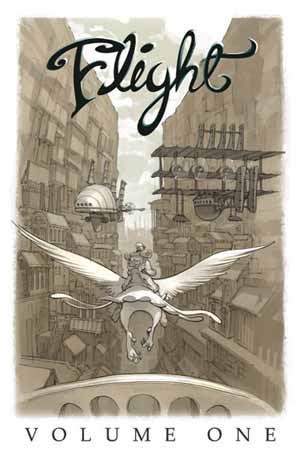

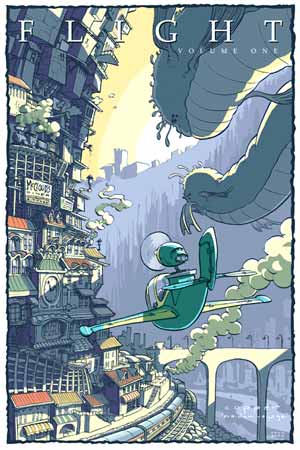

I’ve seen preview pages—he’s only being slightly hyperbolic. Flight (vol. 1; vol. 2 is in the works) is a 208-page color anthology of short works by some of today’s (say it with me) best and brightest: Kazu Kibuishi, Vera Brosgol, Derek Kirk Kim, Clio Chiang, Jen Wang, Erika Moen, Dylan Meconis, Hope Larson, Bill Mudron, Rad Sechrist, etc. etc. —I’ve nattered on about some of these folks before; this is nothing more or less than the next turn in the widening gyre.

It’s going to be an important book—not, y’know, an important book, full of meatily literary comics that wring the meaning of life through the juxtaposition of pictorial and other images in a deliberate sequence; no. For one thing, it’s an anthology, which is always hit-or-miss (though my hits are usually your misses, and neither of us can figure out why she liked the thing with the cat). And there’s featherweight pieces in here: beautiful and charming and evanescent as a soap bubble, pop! Which is fine: it never set out to be an important book, after all.

Nah, it’s going to be important because it’s going to serve notice. It’s going to make a lot of people realize how far along things really are. It might even do some polarizing.

Scott cites four reasons as to why this book is going to be important right now. The second reason, “tribal shift,” does a pretty good job of encompassing the rest. (You could say the same about the web striking back, the metabolization of manga, or the changing face of comics, if you wanted. Me, I’m sticking with the tribes.) —He’s referring to his four tribes map, and if Erika hadn’t let her photo archives slide off into link rot, I’d show you the picture of the placemat he sketched it on for us in Seattle. There’s broadly speaking four ways you can split the [insert creative enterprise here] community: animists, classicists, formalists, and iconoclasts, with the animists across the table from the formalists, and the classicists across from the iconoclasts. (You can line out the semiotic square if you want.) —Sure, there’s other ways you can split them; there’s dozens, hundreds, thousands. So what? This is the map we’re dealing with right now, and with this map, Scott says (and aw, heck, I’ll just gack the thing whole):

In the decade prior to Flight, most of the progressive wing of comics was dominated by the Iconoclast and Formalist Tribes. Walking through the turn-of-the-century expositions devoted to “small press” comics, visitors were greeted on one side of the aisle by roughly drawn “zines” about disaffected white youths with bad jobs, failed relationships and genital warts; and on the other by strange, multidirectional experiments and oddly shaped cardboard constructions with day-glow silkscreen covers. I loved both types of comics (and make no apologies for my alleged complicity in the latter) but by 2004, a change was clearly in the air.

The return of the other two tribes to independent comics found its focus in Flight. The Animists’ love of pure transparent storytelling and the Classicists’ attention to craft and enduringly beautiful settings was evident on many of the anthology’s pages. While so many of the previous generation’s revolutionaries had put raw honesty and innovation over straightforward plots and surface gloss, the Flight contributors tried to have it all—and in several cases succeeded. Flight gave readers something to read and something beautiful to look at again and again. For all the innovations of the rebel tribes, it was this kind of appeal to a broader readership that comics desperately needed in 2004. These artists delivered.

Top Shelf and Drawn & Quarterly and Kramer’s Ergot and Blab! and Zero Zero and Centrifugal Bumblepuppy on back to the grandparents of the iconoclast and formalist tribes, Weirdo and Raw: these anthologies have done incredible, unmistakable things for comics, and it’s impossible to imagine the medium without them, and you’d have to pry my grubby, well-read copies from my cold, dead hands (unless you asked nicely, and then I’d say sure), and Flight is the first major comics anthology I could hand off to my mother, my boss, the woman at the next table, the kid on the bus, you, anybody, and feel pretty damn sure they’re going to sit up and say wow. Oh, I see. Oh, I get it.

Comics as an industry has been its own sequestered, ghettoed hot-house for a very long time, locking comics the medium away in direct-market shops out of the sight of the casual walk-in, held back by the overwhelming popularity of the superhero from people who just don’t give a damn about superheroes. Classicists work in the footsteps of great superhero cartoonists; animists summon up the bubbling Saturday-morning glee, all in color for a dime; and maybe iconoclasts work the rich veins first tapped by the underground cartoonists of the ’60s, and formalists delight in a really spooky borderland between word and image—but they’re still laboring in the shadow of the superhero, and they’re still mostly found in the same shops off the beaten path, snarling at the four-color hand that feeds them.

It’s getting better, sure: it has been, for years, but there’s still plenty of otherwise bright people out there who insist, say, that the swelling popularity of translated manga is just a passing fad, and not a hint of what comics can do when they open up to a broader palette of genres, and put themselves on bookshelves where anyone can find them. —Though that’s unfair: it’s too easy to say the people who agree with me get it, and the people who don’t just don’t. And just about everybody gets it: comics have to open up or die. Comics have to reach out or wither away. Comics can’t just be a monoculture of superheroes. We all know this, and we’re opening up and reaching out, and it isn’t a one-trick pony, not nearly so much as it used to be. Almost everybody gets it. It’s the system that doesn’t: everything from editorial direction to publishing prejudices, from the monopolistic distributor to the retailer’s shelving decisions, from an otaku’s culling of their monthly buy list to a reviewer’s hype—all the hundreds of thousands of little decisions made without thinking, honed by habit to fit a market that sells one thing moderately well to a captive audience. There are good reasons (and bad, and head-smackingly stupid) as to why that system came about, but that’s what we’re all trying to fight, or at least change: habit, and that’s why it’s so damned hard.

Flight is a huge, full-color package winging in from the everything outside that habit. It’s the manga fans, who love comics, but came at them by way of Japan (with a healthy injection of Europop, by way of France). It’s the animation freaks, who find in comics a way to build the worlds they’ve loved on screen on their own, without the expense and (quite so much) labor. It’s the web cartoonists, who’ve built their own gift-economy shadow industry online, utterly outside the purview of a micro-mass market that’s only had room for one genre. It’s anybody who loves the way comics opens up whole new worlds, every panel a shadowbox peering into perfectly personal universes, and here’s where I check Dylan Horrocks’ essay again without doing the heavy lifting needed to engage it fully, but hey: it’s anyone who sees the worlds that comics can build, but didn’t care much for the one (bright and garish and exhilarating and terrifically fun world, sure) that we’ve built with it so far. That’s what went into Flight, and that’s what Flight is bringing into the direct market, and that’s why Scott’s introduction doesn’t read so much like hype. —Well. Except for the bit about Claire Danes. But aside from that.

(It’s solicited in May’s Diamond catalog, by the way, and slated to hit the shelves the weekend of the San Diego Comic-Con, 22 – 25 July. Until then, you can whet your appetite with the preview pages.)

Ah, fsck! Something else I rilly, rilly, rilly need to buy. My wallet hates you; my bookshelf groans at the thought; and I await (eagerly, even).