Utilitarian plastic.

Oh this I’m afraid will not do, I’m sorry, but it’s all manner of much too respectfully not at all right about this, which is just plain muddled and wrong, to the extent I’ve been able to read it—apologies to any affiliate links out there, but thirty-five bucks is just too much for an ebook, and the library doesn’t have it (yet?), and I’m not about to wait out an interlibrary loan and make space in a too-crowded reading list as it is for a book I’ve already been subtweeting snarkily (yes, subtweeting, you say subtooting or subskeeting and people are going to look at you funny, as they should), so: I made do with what I could skim from the river’s free preview, which was more than enough; for God’s sake, the man put scare quotes around the New Weird.

But! But. Begin as you mean to go on, and all: the this in question is Jeremy Rosen’s Genre Bending: the Plasticity of Form in Contemporary Literary Fiction, which, well, let’s go to the book’s preface, Beyoncé and Werewolves:

That premise is that writers of literary fiction have been enthusiastically adopting the genres that historically flourished in popular fiction because they have recognized the utility and endless plasticity of genre.

And there is just, so much wrong, with that premise? I mean, for starters: genres aren’t plastic. Genres are rules. Rules to be at all useful must be fixed, agreed-upon, or at least legible enough to be contested; you can’t thrust your fists if there are no posts. —Genres can be changed, can be bent, can even be forged anew, it happens all around us, but it takes great effort over gobs of time: they’re social objects, genres, and you need to get buy-in from enough other sociable players to make it at all noticeable, much less arguably worthwhile.

No, what’s plastic is the work itself: the way it molds itself to the rules of the genre it’s decided to play with, the forms it takes to dutifully follow this, to provocatively break that, the sinuous moves it makes to run the course set for it, to be recognizable, and yet itself. —One does not speak of the plasticity of the sonnet; one speaks of its rigidity, even as one quibbles over rhyming schemes. One admires the endless facility and ability of the words and work that might be packed within its confines. —And even the most aridly austere free-verser can find themselves envying the energy and wit of a well-formed couplet.

Thus, the enthusiasm mentioned in that premise, and the next wrong thing: the direction of that enthusiasm. Writers of literary fiction, we are told, are enthusiastically adopting the genres of popular fiction, and why not? There is energy, and wit: having ground rules and barriers can embolden flights of spectacular fancy in the unencumbered directions, and sprezzatura’s so much more easily admired when one appreciates the demands that are effortlessly being met. What’s not to envy?

But note what’s missing from this statement of the premise: any notion of bending genre. —Writers of literary fiction have been adopting the genres of popular fiction since the turn of the millenium, we are told, and in so doing,

articulate a theory of genre’s utility and plasticity that explains the newfound allure of genres that had largely been relegated to genre fiction fields, and these writers’ discovery that such genres have not been exhausted by their often-repetitive use in popular culture but remain as malleable and generative as any others. To think otherwise, these writers assert, would be to adhere to a kind of generic fallacy—the notion, familiar since Aristotle, that certain genres are inherently superior to others—or the anthropomorphizing view that genres have life cycles and eventually grow old and die out.

And look at the assumptions that must be made, for this to be noteworthy; look to the flow of power, and regard, from this perspective. —Oh, lip-service is paid to the notion that literary fiction is a genre much as any other, and no genre is inherently superior; it would be foolish not to, since this is a truism of our democratic age, accepted by all. But, that lip-service having been paid—I mean, look to the rules that we are told define this genre of literary fiction:

a focus on individual subjectivity and consciousness; formal innovation and linguistic exuberance; dedication to rendering the intricacies of character psychology and voice; careful attention to style; and treating “consciousness as the primary site of experience, the medium through which oppressive workings of power are felt and the vehicle for generating resistance to them.”

You know. The good stuff. The good mid-(last)-century stuff. —There’s no mention of bending genre in this statement of the premise because the adoption of genre forms by these literary writers—say their names with me, now, Margaret Atwood, Michael Chabon, Jennifer Egan, Louise Erdrich, Kazuo Ishiguro, Chang-rae Lee, David Mitchell, Cormac McCarthy, Ian McEwan, Haruki Murakami, and Colson Whitehead—this adoption is itself the bending: literary writers do not by definition write popular fiction, therefore, their adoption of the genres of popular fiction must necessarily bend those genres to some new form, with the subjectivity and linguistic exuberance and careful style and intricate psychology that were presumably lacking before such literary interventions. —Sure, everything’s a genre, and no genre’s inherently superior over any other, but nonetheless the underlying logic’s nothing but a kinder, gentler form of McCarty’s Error: “To label The Sparrow science fiction,” he once said, in an age-old review, “is an injustice and downright wrong.”

If you wanted to look to the actual bending of genres, the forms and rules and audiences and conversations that make them up, and change over time, in slow irreducible gradations and suddenly punctuated equilibria, why wouldn’t you look to the very popular fictions as well, where the rulesets of many and various genres have been bent and intersected, implicated and imbricated for centuries, where locked-room murders are set on generation starships, and happily-ever-afters played out within the kingdoms of high fantasy, where the very act of combining and bending genres has itself developed its own rules and conventions and (yes) genres; and where (yes) the tools and rules of literary fiction have been picked up, kicked around, put to use, and given back, just as altered and renewed as any other convention? Why limit yourself to this (very) recent and (very) particular phenomenon?

Because that’s where the clout is, yes, thank you, Willy Sutton. —I mean, maybe Rosen does do this, or at least gestures toward it, somewhere in the rest of his book that I did not read; maybe Sparrevohn glossed over it in his review to make other points, I mean, time and space are limited. But I’m not optimistic on this front. To state that it’s but anthropomorphizing to assert that genres have life cycles, grow old, die out (of course they do! The attention of the audience is a critical component of any genre, and that attention waxes and wanes!), to so confidently state that, one must really have grappled with (say) Joanna Russ’s magisterial essay on The Wearing Out of Genre Materials, to find a way beyond the cycle she delineates, to reveal the mechanisms that allow these materials to recombine and recur, again and again, to explain why vampires suddenly worked once more (and fell once again to decadence), to actually get at the engines that bend genres, and the conditions that render them plastic. But: the index (which the river’s free preview allows one to peruse) lists Russ precisely once in Rosen’s book, on page 10, where there’s a gesture toward the “politically motivated work to come out of genre fiction fields—like that of” (say them with me, now) “Octavia Butler, Samuel Delany, Le Guin, and Joanna Russ.” —Better by far had those works been read and examined and discussed (as a start!), instead of just checking their names.

Always already brought back.

Oh, hey, it’s the 24th anniversary of this here blogging megillah. Favored gifts include opals, lavenders, and tanzanite, which, apparently, is the blue to purple variety of zoisite. —What went on last year? Let’s see: I tore up empathy, I wrote about what I’ve done with AI, I discovered some poetry from my grandfather, I didn’t so much like a very good book, and I was rather a bit more indulgent than, perhaps, usual. Let’s see what comes next.

Remember this, our favorite town.

I’ve mentioned before, how I don’t so much remember my dreams as such; what I do remember is usually dredged from the not-quite-dreams you have when you’ve popped awake at two in the morning out of some atavistic polyphasic rhythm, and you’ve micturated and drunk some water and maybe checked on the dogs and climbed back within the (at this time of year) still deliciously body-warmed bedclothes, and you’re lying there thinking idle thoughts as you wait for a sleep which never seems to come until it’s three thirty or four in the morning and you realize you’ve been asleep, that those idle musings had some time ago slipped over some inscrutable limen to become not-quite-thoughts, and now they’re slipping away like sand, and so anyway, this morning—but I should back up a moment. I don’t so much remember my dreams, not as such, but of what I have brought back, over the years, my dreams set in an urban environment are all, pretty much, set in the same urban environment, a city I’ve never been to, a city that doesn’t exist out here, and I think some of this might be the fact that I’ve been living in the same city for thirty some-odd years after twenty some-odd years of peripatetic restlessness (by the time I was 18, I’d lived in 20 different houses)—it’s a pleasant city, to be sure, walkable, with a good public transit system, the lines and maps of which have helped me fix the shape of it in my head, there’s a river, runs west to east, and most of the downtown is in the north bank, and there’s a complicated freeway interchange along the river, it’s all rather a bit like Portland turned on its side, but there’s also an almost-island on the east end that has a university and an arts district and also some lovely public gardens, I’m not sure where I got that, but anyway, this morning, lying there waiting for the sleep that had already bagged me, I found myself looking over a map in a book, the sort of map that’s the frontispiece or tucked in the end-papers of those sorts of books, and I said, “You know how I have the same city I go to when I’m dreaming?” or words to that effect, and the kid who was with me but pretending to be my brother (which is odd, the kid’s a much better fit for my littler sister), the kid says, “I always think it’s weird that you have that,” pretty much verbatim, but I’m pointing to the map, and I say something like, “I think it’s based on all the time I’ve spent looking at this, the city of O———, in Zimamvia!” and reader, I’m not being coy, I really did say something that began with the letter O, but was otherwise entirely illegible in the moment, not forgotten later, and anyway the map we were looking at in a book that I’m fairly certain was not by Eddison was very clearly much not a map of Zimiamvia, I’m pretty sure it was a pretty prosaic map of the Black Sea, and the city of O——— I was pointing to was up by the Sea of Azov. —Oh, and the old saw about how you can’t read in dreams? Or more specifically, you can dream that you have read, but the actual letterforms-to-concept process of reading is impossible in a dream state? I mean, I can? In small bursts. Maybe dream researchers need to talk to more typesetters and printer’s devils.

The wandering I.

So yes I said I was going to re-read Zimiamvia, yes, but the thing about pulling the book off the shelf (it’s a big dam’ book) and assembling the supplemental texts and monographs and picking up a new notebook and finding the right pen is it all becomes, well, a Thing, and Things can be put off, and I anyway I also said, which I didn’t tell you, or at least not here, I said the other thing I might do would be to start pulling together my various disparate thoughts on cinematic prose into something of a defense if not a manifesto (I am not the sort for manifestoes, ask anyone), but the trouble with that is everything I’d have to say is prescriptively reasoned from principles I’m applying myself, which don’t end up describing anything but what it is I’m trying to do, which, I mean, seems more than a little indulgent—what I really ought to be doing is to survey the field, marshal some (other) examples, draw from them what it is this cinematic prose, this screen-like æsthetic, is doing, or trying to do, but there again, see, I’m assembling tasks and goals and texts to find and read and would you look at that, it’s also become a Thing.

And anyway, besides: a lot of the cinematic stuff downright sucks.

Which is maybe why some sort of defense, I mean certainly not a manifesto but maybe a set of some sort of proposed, I dunno, guidelines? considerations? alternatives? something, anyway, is perhaps, maybe, in order, to show a way to make it better, if it’s bad, or at least lay out some possibles that might be could be reified with some modicum of thought, but—but. That would entail pretending what it is I’m doing, or think I’m doing, is in any way better or more considered or grew from thoughts worth the thinking; would mean setting myself up however haphazardly as an expert, or at least an authority, which is unseemly; and now this Thing is rapidly becoming a Chore, and so we set it aside, I mean, I’m behind on the next novelette as it is, you know, the actual doing of the cinematic prose I’d be thinking of talking about instead. So! Zimiamvia it is.

Except.

I was clearing out old browser tabs, as one does, and fell into reading a Baffler take on the post-postmodern novel, as one does, and here, in this article I’d originally opened God knows how many months ago, about (in part) a novel I’m, and no offense or insult intended here, but I’m not at all likely to ever want to read, honest, it’s called UXA.GOV, which was apparently blurbed as “an unhinged occupation of the cinematic mechanism of Robbe-Grillet’s novels of the ’70s,” which novels the article goes on to describe as novels in which “tropes of cinema and genre fiction are playfully misappropriated as vehicles for Robbe-Grillet’s perverse preoccupations.” —And, I mean, I knew the name, Alain Robbe-Grillet: French, experimental, perverse, sadist, misogynist, that’s what’s jotted on his index card in my memory cabinet, in which he’s filed next to George Bataille (French, experimental, sadistic, perverse, and their names both end in disappearing consonants) who, because his most famous book or at least the title I can most readily bring to mind is Histoire de l’œil, the Story of the Eye, is filed next to that comic Jodorowsky wrote for Mœbius, the Eyes of the Cat (Chilean and French, perverse): thus, a glimpse of my personal filing system. —So! Here’s Robbe-Grillet, the French experimental sadist, and I’m being told his fiction, or at least what was written in and around the ’70s, is cinematic, and, well.

(If I’d been paying attention, I might’ve noticed him earlier—there he is, after all, in the introduction to Marco Bellardi’s Cinematic Mode in Fiction, mentioned with Hammet and Vittorini and Ballard as possible touchstones, but I was mildly dreading the approach of something called the “para-cinematic mode,” and skipped on by.)

Curiosity sparked, I went surfing, which is still possible, even in an enshittified age, and found, thank you, London Review of Books, here’s Robbe-Grillet railing against Balzac’s

omniscient, omnipresent narrator appearing everywhere at once, simultaneously seeing the outside and the inside of things, following both the movements of a face and the impulses of conscience, knowing the present, the past, and the future of every enterprise

and here he is, insisting on the primacy of the object, the material, the surface, denying even the possibility of depth:

The reader is therefore requested to see in it only the objects, actions, words and events which are described, without attempting to give them either more or less meaning than in his own life, or his own death.

But—but! Be careful: here he is with the rub of the green:

…no sooner does one describe an empty corridor than metaphysics comes rushing headlong into it.

The visible world is merely their skin. So I’m nodding along with the beat, here. —The point, for me, with the idea of cinematic prose or the screen æsthetic or whatever we’re going to end up calling it, cinematic, I think, it’s cooler, but anyway, the point has always been not so much to ape or mimic or reproduce this or that technique of cinema qua cinema in prose, to write a montage or a pan or a smash-cut: that can be done, sure, certainly, and is even a part of it, of course, but it’s not the point. The point is to take the limitations imposed and implied by the form of cinema and apply them as ground rules and organizing principles to prose—tennis, as more than one poet has noted, is no fun without a net. So:

- The point of view is at all times relentlessly focused on a specific here and a particular now: no speculating forward or ruminating backward, no pondering elsewhere, idly or otherwise.

- No conclusions are ever directly drawn. No inferences are explicitly made. Judgment is out of the question; metaphor and simile become unfortunate compromises.

- What is described is limited to what might be perceived by a camera, or a microphone. Anything else—touch, weight, temperature, smell or for God’s sake taste—they’re all too suggestive of a body, and thus of a subjective presence, and are to be avoided.

- Essentially, and crucially: there is no interiority, whatsoever. Interiority is the bunk.

What’s being evacuated, in the end, is any trace or notion of a narrator—which is patently absurd, of course: narratives must have narrators; tales must have tellers; what am I trying to hide? And where? —But there’s power in hiding, in cloaking, in what’s done where you can’t see: negative space is a vital component of any composition. I’m building empty corridors with the hope that you, dear reader, will fill them with metaphysics—but the shapes of those corridors can’t help but suggest and direct whatever ghosts you bring.

It’s not as if I set out to write like the cinema, or was impelled in that direction by a disdain for the smugly blinkered omniscience of so many third persons. The technique and the philosophy assembled themselves concurrently, as I was tinkering with stories and criticism way way back in the day on alt.sex.stories.d: something about pornography would seem to encourage a flatly objective approach, and a narrator to get out of the way. (For me, at least. Mileage varies, and all.) But at this much later point, I mean—this is how I write the epic, and the epic is what I write; I need to be able to say something entertaining if not intelligent about it, at salons, and cocktail parties; thus: technique, and philosophy.

Still: it was some kind of surprising to see arguments that I might very well have been making issue from the fifty-year-old pen of the soi-disant bad boy of French letters, a maître à penser of the nouveau roman whom, and no offense or insult intended here, but I’d never been all that interested in reading—it’s validating, sure, I suppose, but also disconcerting, what with the perversion and the sadism and the misogyny and the hebe- and pædophilia, and what with these arguments being made about and in service of the writing of his own infamously pornographic works. These are hardly new or unique or surprising arguments, but it’s still very much a this is the guy I’m standing next to? moment.

The library had copies of Project for a Revolution in New York and Recollections of the Golden Triangle, squarely within “the cinematic mechanism of Robbe-Grillet’s novels of the ’70s,” so I snagged them to have a look for myself, as one does. —Right off the bat, Project is a first-person text, and Recollections—well—features first-person narration; rather than being evacuated, the narrator’s right there, in the way, hectoring, chiding, speculating, inferring. What’s cinematic is more piecemeal, aping, mimicking, borrowing: a very visual approach, yes, as well as a cavalier abruption of transitions that tends to be noted, and commented upon, as it goes. (An earlier novel, Jealousy, seems ironically rather closer to my mark, with its deliberately if conspicuously absented narrator, but even here, dialogue’s condensed, summarized, subject to the judgment of someone supposedly not there.) —Project has an appealingly slippery beginning, and I very much enjoyed the energy of the opening of Recollections, but: and you can tell me all you like that the tortured women and girls are not women and girls but texts subjected to figurative mutilations, it’s all metaphor: and I wouldn’t want to dismiss him as little more than a dirty old man: still. The dirty old man bits are boring. —He’s excessive, yes, but very (sadly) conventional in his excesses; somewhere along my Robbe-Grillet surf I bumped into someone noting that his taste in lingerie is very Victoria’s Secret, which bon mot I’ve lost and can’t directly cite, apologies. His id is freed, sure, to set down whatever he might like from his subconscious, but none of it’s interrogated or investigated—merely indulged.

And it’s all a little too Screwfly out there right now to put up with any of that for whatever else might be on offer.

The only reference to any world outside of this setting is the description of a global economy whose elaborate rules and regulations, tariffs and taxes, aim at collecting wealth, either to maintain social status, or to support a corrupt state or government whose interest in money is rivaled only by its own complicity and participation in the perpetration of sexual torture. The socio-economic world of the book might not stand up to scrutiny as a model republic, but it does, overall, reflect Robbe-Grillet’s mistrust of laws, authority, and righteousness.

—the Translator’s Preface to

a Sentimental Novel

Speaking, then, of women in trouble—I noticed the other night that Lynch’s Dune had returned to Netflix, so I put it on as I was cooking (pasta with the simple kale sauce, I think); I like the rhythms of it, the soothingly whispered internal monologues, the charming hoke, Brad Dourif’s tightly hinged mentat, Big Ed drawling Stilgar’s stilt, and dang if those worms aren’t still somehow majestic. But this time I happened to look up from whatever it was I was doing (slicing ribs out of kale leaves, maybe, while the water built to a boil) as the leaving Caladan sequence began—

—and was struck by a couple of notions as it unreeled. The first, as the bizarrely mutated and poorly matted Guild Navigator floated up through spice-soaked light to fold space, and travel without moving, is that this time, I was immediately, almost painfully struck by how unutterably similar the moment is to a moment in Part 8 of the Return: the Giant, floated slowly up in a corner of the extra-dimensional movie theater, tilts supine as a glittering galaxy is spun about his head, and the golden pearl of Laura Palmer that he creates is doubled by the worlds the Navigator spits. —So utterly unexpected, so magically, shockingly beautiful, those painfully awkward forty-year-old special effects striving to depict something impossible, this electrifying connection with something so much sleeker, more assured, just as mystifyingly impossible. The hair stood up on the back of my neck; I went back to slicing kale.

The other notion, less disruptive, more germane: a moment earlier in the Dune clip—it’s all a bit stagey, elements almost collaged onto the screen, a planet, a moon, the great distant column of the heighliner, the gracefully orderly arcs of countless Atreides shuttles lofting slowly, stately toward it. Nothing looks or feels “real”—the lighting, the motion, the construction of the ships—but the effect is still somehow effective. It’s satisfying, in a way that meticulously worked out computer models with reams of lore behind every panel and strut to show us what it “really” would’ve looked like would not, could not, I mean I’ll step it back to might not, but that meticulousness and the working-out and the drive toward a “real” obviates the dreamlike meditativeness Lynch is striving for, that would short-circuit depiction and perception to reach straight instead for the experience, in all the many and varied senses of the word, the world, of something so unutterably impossible. —I found myself thinking of, of all things, Ladyhawke, and of how the transformations were not depicted, no, but suggested—shots of eyes, and feathers, a wing, spread, and the rising sun, which were all so much more effective, so much more satisfying, than the most “realistic” depiction of Michelle Pfeiffer morphing into a hawk could ever have managed to be.

An objective medium—cinema—reaching for subjectivity when its stock-in-trade fails. A subjective medium—prose—reaching for objectivity to force those moments when its stock-in-trade will fail. —In either case, in both cases, by frustrating expectations of what can or should or ought to be done, by leaving negative a space that positively should’ve been filled, the art, the expression, invites requests demands allows the reader, the viewer, the audience to step in, to fill in, to become the God of this or that particular gap, to assemble these subjective glimpses into a rendering of what it might’ve objectively been like, to shuffle these objective glimpses until the subjective meaning of them all becomes graspable if not clear.

Cinematic prose; prosaic (ha!) cinema. Anyway, that’s what I’ve been thinking of. How’ve you been?

No, when you’re in it, you’re in it. You believe in it, otherwise it’s just having fun, and I’m not interested in that.

A billion dollars is a weapon of mass destruction and must be regulated as such.

“But the reality has been far different. Last year, three of Starship’s five launches exploded at unexpected points on their flight paths, twice raining flaming debris over congested commercial airways and disrupting flights. And while no aircraft collided with rocket parts, pilots were forced to scramble for safety.” —Heather Vogell and Agnel Philip, with graphics by Lucas Waldron

Where were we.

Before we were so desultorily interrupted? Sorry to have left That Name pinned to the top of the pier for so long; let’s maybe look at it as sort of a metaphor for the bizarrely outsized impact his death and his works have had, even as his life and his work haven’t managed to break into the popular consciousness enough to even bother being forgotten. —I’ve been writing, of course I’ve been writing, writing the epic, and this was the year the third season got launched, which was a bit of work, but when that work is not going well, which it wasn’t, (which it isn’t, also, at the moment), then it tends to glower: the Scrivener window on that monitor over there, still waiting for its daily quota to be filled, it feels like an indulgence, typing up something else for somewhere else. (I really would rather it glowered when I’m off Blueskying, instead.)

—Let’s see, let’s see: I finally got to read the Elemental Logic books this year, which I adored: queerly grounded epickesque fantasy with the courage of its convictions to haul the story down some rather unexpected paths, and the way the magic is embodied in how the characters think is, well, magical. I’m late to this party, as I usually am, but it’s a good party, and there really ought to be more people here.

Then I went and read a Sudden Wild Magic, because Wm Henry Morris had to go and mention it on the aforementioned Bluesky: a really odd book, for one that’s so mildly, insistently normal: airy whimsy played po-faced for life-or-death stakes, and even the nice characters can be rather offhandedly brutally ruthless; I mentioned elsewere it felt like the first draft of the Bene Gesserit, but it also has the distinct air of a roman à clef of a writers’ group or circle or community, rather like How Much for Just the Planet.

Kelly Link’s Book of Love was—I mean, I didn’t not like it, there were beautiful sentences and loads of gorgeous moments but—altogether, it was somewhat ramshackle? Which is not the most perspicacious thing to say about the first novel written by an acknowledged master of the short story, I suppose, but there it is: Magic for Beginners, at less than a tenth the size, felt far larger and more epic.

I’m currently in the middle of Cecilia Holland’s only SF novel, Floating Worlds, which I could’ve sworn I’d read before, ages ago, but no, no; I think I’d started it, once or twice, but must not have gotten all that far, and somehow, dreamlike, it had merged with the memory of having read the Solarians in Venezuela at a very young age to make up the completed shape of a book on a shelf in the memory palace. —The Holland is much better than the Spinrad, though it’s dicey as hell on a couple of fronts; it hasn’t wrong-footed yet, and Paula Mendoza is up there on the list of favorite characters, so.

Next, I’ll probably be gearing up for a re-read of Eddison’s Zimiamvia books. Sean Guynes, as part of his ongoing essays on the Ballantine Adult Fantasy books, went and said some things about Zimiamvia that, I mean, it’s not that I think he’s wrong, or disagree on any pointed specific, but nonetheless my back was got up a bit: these are not dull and—well, all right, yes, there are patches that are rough going, but—but! these are not lifeless books. —There’s a lot of Eddison in the epic, and it’s specifically Zimiamvian Eddison: the Worm Ouroboros is great, and Lord Gro is also up there on the list of favorite characters, but I bounce off that book’s Boys Own Demon Lord protagonists, who never manage to catch me the way that Barganax and Lessingham have done, and Horius Parry, Fiorinda, yes, Antiope, even Anthea and Campaspe—toxic yuri avant le lettre. Among the prim and proper strait-laced taproots of what it is we hereabouts and now call “fantasy” (I mean, there they are, kicking off Lin Carter’s collection of Adult Fantasy books for Ballantine), these books are unexpectedly horny (but without the faux-courtly lookit-this-pinup say-no-more energy of works such as, say, Lin Carter’s), with an unexpected but undeniable thrill of queerness running through them, or at least to be read into them. That’s (some of) what electrified me, these glimpses, in passing; I want to go back to them with a more consciously discerning eye, to see how much of this possible there there really is in there, or might be. So I’m searching out essays, stashing bookmarks, the magic of interlibrary loan has secured me a copy of Anna Vaninskaya’s Fantasies of Time and Death, which on its own will have made this endeavor worthwhile, I think. Last time through a couple of years ago I read the OG Ballantine editions; this time I’ll be going back to the Dell omnibus from 1992, buttressed by the scholarly armature assembled by Paul Edward Thomas. —So there’s that, I guess, to look forward to.

Otherwise? I mean, what is there to say, in these dregs of an anno truly horribilis? The country’s on the verge of a sestercentennial no one seems to want to notice, much less celebrate, embarrassed as we all are, perhaps, at being the only country in the history of the world to have twice elected Donald John Trump to the presidency. I’m about to step over a threshold that will have me slouching toward a fifty-eighth birthday in the rubble of destructions already wrought that we can’t yet perceive. I have a day-job that is vital and important with co-workers I admire and adore at the top of a profession I accidentally fell into twenty years ago, and I do not make enough money to support the responsibilities in my hands. I write the work I want to write on terms I’ve set myself for an audience of dozens. I’m a fat and balding greybeard, I drink too much, I’m sure I’d be smoking the occasional cigarette again, if honey-tipped kreteks could be got for love or money. I should do more cardio. Every morning I wake up suffused with such dread that I find I cannot move until ironclad routine sets me in motion: cats must be fed, coffee must be brewed, words must be written, get up and put on the pants. “I do not think I know where we will be in ten years,” I wrote, back in 2006, and Jesus, would you look at us now.

—But still: I pay my taxes. I chop the wood, I carry the water, and I sit down when I can with my books and papers and do what I still love. —That’s gonna have to be enough, for now.

Talent on loan from God.

Really looking forward to the day I manage to think about Charlie Kirk as often as I think about, ah, that other guy. Also a prick. Also dead.

For a good return you gotta go bettin on chance—and then you’re back with anarchy.

Just so we’re all clear: the City of Portland is removing protections legally applied and mandated by law in an attempt to prevent the utterly and thoroughly illegal rescission of three hundred and fifty million dollars’ worth of federal funding, legally allocated by the duly elected representatives of the people who put up the funds, all because no one can afford the amount of time it would take for the wheels of justice to slowly grind their way to finding precisely that illegality and impotently enjoining what’s already been rescinded until such time as the Supreme Court throws out any such exceeding fine work without explanation from the illegible gloom of the shadow docket, but—but! Having done so, the entire city must now spend the rest of the year, the term, the reich huddled quietly in a corner hoping this will all be enough, but it’s never enough, and anyway if at any later point we happen across his mind in the slightest slantwise fashion he’ll just take it all again, and more besides, and what will we give up next?

Thamus Agonistes.

“Now that people are turning to ChatGPT for spiritual insight, though, I wonder if I finally have to admit it. Obviously here again we are dealing with what seems like a quantitative change—people are using the machine to shuffle religious clichés, where previously they just half-consciously did it themselves. But the qualitative difference is that the insights of ‘Buddy Christ’ could always be corrected against the unchanging text of Scripture. When there is no longer an external anchor like that, when the divine revelation is ‘customized’ for each and every reader, something has changed. Again, this is not to say that what happens to be in the Bible is necessarily ‘better’ than any given ChatGPT transcript—presumably it’s often worse. But a point of leverage has been lost. Counterargument is no longer possible in the same way. And insofar as that point of leverage, that external source of authority, was how ‘God’ functioned in traditional monotheism, that means God is dead.” —Adam Kotsko

When you get caught

Between the Moon and

Second person, chat. I just don’t know. —Oh, it can be done well, anything can be done well, but the curve on second person is some kind of steep. Comes in three basic flavors, the second person: there’s what you might call diegetic second, where who’s being addressed is a specific second person, firmly ensconced in the story as a character themselves, so that it’s really more of a text within the text, you’re distanced from the point of address—it might as well be an exchange you’re eavesdropping, an epistolary you’ve somehow intercepted. —The next you might call more of a diffuse, a second person that, yes, is addressed to you, Dear Reader, but not too specifically: there’s entirely too many of all of you, and far too wonderfully varied; best to be disarmingly vague—and so, in an heroic effort not to break the spell, it can all-too-often never manage to cast one in the first place. —The third second person? Direct: an attempt to square the circle and have it all, the author reaching out of the text to grab you, yes you, Gentle Reader, by your lapels, but also the author would insist on the lapels to be grabbed, the type and tailoring, the heft in the hand, particular lapels suited for the specific you the author has in mind, a you you’re dragooned into playing, will you or nill you: it can’t help but hector, this voice, and no one likes being hectored, though even this can be done effectively, even well—one thinks of Eddie Campbell’s How to be an Artist, told in a striking second-person imperative, but that’s comics, and there are so many other things happening to détourn that voice. —Like I said. It’s hard.

So when I tell you The Spear Cuts Through Water is written in the second person—

(“You were thirteen, you think,” you’re told, quite imperiously, and I don’t know about you, but while I’m game enough to pretend to have memories I’ve never had, I’d just as soon decide for myself how reliable they are. Though I must admit I remembered this particular directive as landing rather more forcefully that it does upon re-reading; I was surprised by how—mild?—it turned out to have been. Thus, a grain of salt.)

—I mean, it isn’t, not really: it’s actually a first-person text. I mean, yes, every narrative is necessarily written in the first person, but Spear’s only somewhat coy as to this fundamental truth: your narrator’s there, on the page, on the stage, referring to themself always in the third person as “this moonlit body” (never “a,” or “the,” or “that” moonlit body, but always and reflexively “this”): the love-child (soi-disant) of the Moon and the Water, impresario and headliner of the showstopping antics of the Inverted Theater, that reflection of an impossibly tiered pagoda floating on the surface of the Water, bathed in the light of the Moon.

This is the structural triumph of the book, and what I greatly admire: that the epic as such is a theatrical production, drama and dance performed in that Inverted Theater in a dream that you’re having, told to you, narrated necessarily because it’s actually unfolding from the pages of the book in your hand, written by Simon Jimenez, but set that aside, because as you’re dreaming the story you’re reading, this moonlit body reminds you of your memories, memories of your much-later life that spark, that are sparked by, incidents in that story, this epic of the old country from so long ago. These layers add a richness that carries what’s really a rather focused (and single-volume) work just over the threshold of epic, but the movements between and among them are so surefooted that you’re never lost, never bogged down in metashenanigans: you marvel, instead, as background characters, bit players, minor figures, NPCs (in the [shudder] parlance of our [shudder] times)—as the story’s performed, the actors playing them in the Inverted Theater will step up to speak for a moment, a passage, a phrase, a snatch of internal monologue become spotlit soliloquy, a bit of italicized free indirect slipped in to trouble the narrative flow, to comment, contest, open it up, all these non-protagonists, from the usual monotone of one word set carefully, deliberately after another toward something more of a polyphony. Such a simple trick! But deceptively so: it’s only the theatrical conceit that allows it to work as well as it does, the artifice of performance excusing the artifice of italics, and of the courtly stilt needed to better fit with the flow of this moonlit body’s narration—appropriate enough for an epic, to be sure, but not so much for a glimpse of a stream of consciousness, unless, of course, that stream’s been polished by rehearsal, shaped and timed to fit: a performance, each of them, however glancing, however brief.

Marvel, then, and marvel again, as, once established, these moves are elaborated: the Moon’s dialogue, say, which is handled the same way as these extra-narrative irruptions; when She speaks, She steps up (or the actor playing Her) to tell you what it was She said, back in the day, impressively at once more immediate and yet more distancing. Notice that neither of the protagonists is given a chance to directly address you—not until She passes, passing on a modicum of Her power, which they use, this technique, this trick of the book, to talk to each other—a graceful melding of form and function, all built before you as you read—and when it all comes together, levels and tricks and elaborations folded together to make the apotheosis if not the climax of the book, as the narrative conjures a deceptively simple trick of the theatre to collapse event and representation, story-time and telling-time, actant and audience, reaching up to grab you, yes, you, you there, by whatever lapels you’re wearing, and haul you in—it’s electrifying. For this, this marvelous conceit, Spear deserves every accolade it’s received, and very much a prominent place in whatever broader conversations we have going forward about technique, about prose and structure, form, novels and epics, you know: fantasy.

But. Having said all that. I feel a little sheepish, here, I mean, every word is true, don’t get me wrong, but. I just, y’know. Didn’t like it very much. The book.

Some of that—a lot of it, really—is due to the climax, which has to follow the admittedly staggering act of that apotheosis. Two new characters crowd the (metaphorical) stage, both mentioned previously, to be sure, but nonetheless focus is pulled as the work required to bring them on gets done, work that maybe should’ve, could’ve been done earlier, along the way (not so much Shan, daughter of Araya the Drunk from all the way back at the beginning, to whom the protagonists are to deliver the titular Spear, but the Third Terror is a magic trick the book tries to pull off not so much by misdirection, hoping you’ll maybe forget for a time, but instead by apparently forgetting itself until this last-minute dash)—all for the sort of action-packed hugger-mugger that passes for third acts these days in superheroic action flicks, a widescreen smashemup that works even less well in prose, no matter how artful. Armies clash without the city walls! Within, the Third Terror has become a kaiju, obliterating buildings, tossing back people like popcorn shrimp! The ocean has withdrawn, stranding treasure ships and shoals of dying fish! An unimaginable tsunami, impossible to withstand, is just hours away, still hours away, yet already it swallows the horizon! To anywhere, one of the background characters tells you in their moment in the spotlight, of where the supernumeraries all thought to flee; It was too much. There were five ends of the world, and to run away from one meant running into another, and damn, you feel that, but not in a way that’s maybe intended. Why five ends of the world, when but one is more than enough? (Shades of thirty or forty sinking Atlantises, or those in the path of a super-typhoon.) —This apocalypse goes to eleven!

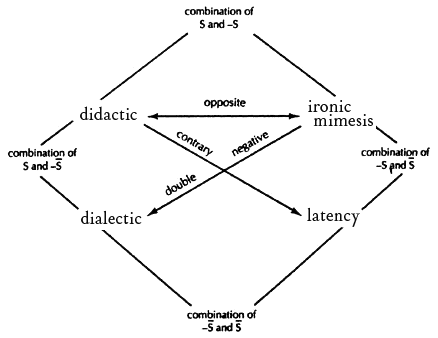

But a climax is made from what’s come before, and though the book’s conceit is a magisterial wonder, I’m afraid it’s elsewhere thinned, and weak. —The Spear Cuts Through Water is a portal/quest fantasy, to reach for our Rhetorics: one that broadly straddles the didacticism of that mode to lean hard on both the knowing dialectic of the liminal (it may seem odd, to refer to something so openly, baldly itself as “liminal,” but the book blithely skips back and forth over every limen that would mark its place) as well as, and but also, I think, to its detriment, the ironic mimesis of the immersive:

The epic (as such) begins with a brashly thrilling overture, already in incipient crisis, plots a-swirl about the court and a garrison, a deeply seeded rebellion apparently a-brew, only for the table so deftly set to be entirely upended by an explosive inciting incident and you’re off to the races, rather literally, across the breadth of the old country, for the next five days—a terribly focused epic, as you might could see; the pace and the scale of it would tend to militate against the sort of didactic lore-dumps (no matter how artful) that are a hallmark of the portal/quest. And, as you know, Bob, most folks don’t so much go around explaining to each other the differing details of what they’re seeing and doing as they go about their day, simply for your benefit, Dear Reader. Thus, the logic of ironic mimesis, as they take for granted what you might find fantastical—but! Consider the tortoises:

All of this theater for the benefit of the creature perched on the high chair.

The tortoise’s gaze was set on the First Terror. “The Smiling Sun wishes to know your thoughts,” the mad creature giggled. “From all the evidence laid before you, to what side of the line does your heart lean?”

The Terror looked up at his father’s surrogate and then down at the wet dog of a man in the center of the room. Thirty-three years. And without a further moment of consideration, he said, “My Smiling Sun, this man is guilty.”

The tortoises turn out to be rather important, to empire and story, and this is your first—well, it’s not really a glimpse, is it? You don’t really see anything, not in this scene, just a handful of words, references to a tortoise, a mad, giggling creature, the Emperor’s surrogate, but without any attempt to body forth the referent (an aimless bobbing of a too-small head, light glancing from the shell of it, the smell, for God’s sake, or what the actors in the Inverted Theater might be doing, to conjure this image for you)—well, you’re at a loss. You’ve seen that everyone at court wears stylized animal masks, and this is (I believe) also the first indication that certain animals here in the old country can speak—I, at least, for a couple-few pages, thought maybe it was a eunuch (court; giggling) in a tortoise mask perched on that high chair. (How, exactly, can a tortoise perch, per se, anyway?)

There are other such lacunæ, some eventually remedied, some not (I still don’t have a clear idea of how the Road Above and the Road Below work, say), all adding up less to a sense of playful, ironic reserve than a frustrating lack. And there’s a slapdashery to some of the details that are presented: eight emperors have ruled since the Moon stepped down out of the sky; eight generations, as each has demanded a son of the Moon, and raised him up in turn; eight Smiling Suns that have beaten down on the old country in an endless, rainless summer—I think? It’s hinted, alluded to, but never quite clear, or as clear as it should be, whether a drop of rain has fallen in all that time, but certainly, it’s hot, it’s dry, but never perhaps as dry as it could be? Should be? Might? —It doesn’t feel like a world that has learned to live without something so important as rain, or moonlight: eight generations also without a Moon—just an empty starless patch of sky known as the Burn—but you’re told at one point that “The Burn in the sky smoldered like a black moon above their heads.” A strange simile, to liken the lack of a thing to the thing long gone.

There’s a tension, between a looser, goosier f--ry tale world, a knowingly artificial, liminal world, and a world more brutalistically immersive, a tension you can play with, certainly, build things from, and with, anything can be done, and done well, but of course it takes work, and consideration, neither of which I don’t think really got done here, not as to this angle, and maybe you disagree, maybe it didn’t bother you all that much, maybe you’d say it’s subjective, but then there’s page 58 of the 2023 Del Rey paperback edition:

Through the courtyard he walked, slipping back into his sleeveless shirt as he passed the night shift at work. Soldiers unracking weapons and polishing the blades and spear tips smooth with oiled cloth, bouncing moonlight off the curved metal.

Eight generations the Moon’s been locked away in a cave under the mountains, and they’re bouncing what, now? —A small and simple error, sure, a slip of the metaphorical tongue, reaching along well-worn grooves for the sort of detail that this sort of phrase in that sort of scene would usually call for, but: in a liminal, ironic mode, where you’re on guard for the slightest clue as to what the ostensible narrative maybe pointedly isn’t telling you, such a slip can be fatal to the knowing dialectic between the writer, yes, and you, the reader. Moonlight? you’re thinking, wait, is the Moon’s absence maybe not really the absence of a moon? Is there something unexpected going on? What could it be? and by the time you trip to the fact that it’s nothing, just a slip, the damage has been done.

But if it had been caught? If it had been torchlight instead, or starlight? If it hadn’t bedeviled me as it did, if I’d been in a more charitable mood, or mode? Still: the world of this epic, the old country under the Smiling Sun, is unrelentingly brutal and viciously violent. The epic begins in incipient crisis, yes; it is—relentlessly, viciously—focused, on the events of the next five days; such a scope and pace will lend the proceedings a tendency toward packing on the action, and that it does, to such an extent that when it seeks to vary the tone, to reach for a moment of shock, or awe, or o’erweening cruelty, it overloads to what becomes a cartoonish degree: on the morning of the second day, as the protagonists pole their stolen boat through the waterlands of the Thousand Rivers, they come across a fishing village that has been massacred:

It was blood. Everything was painted in blood. It killed us all. As if someone had taken great big bucketfuls of blood and doused the dock boards with it, and the boats, and the walls of the houses that made up this small and now silent village. It came through the windows. It broke through the doors. An arm hung off the side of the dock. When their rightmost pontoon bumped into the dock strut by accident, the arm slipped off the edge and gulped into the water.

It’s arresting—in the moment. The protagonists react—discomfitted, appalled—in the moment. But it fades as you proceed, given what you’ve already seen, what you will see, violences great and terrible and intensely, cruelly personal, the massacre at the Tiger Gate, the slaughter in and among the barges of the Bowl, bodies folded into boxes and coins of flesh, the Second Terror’s horrifically capricious punishment of his dancers, the farmers ridden unnoticed beneath the hooves of the First Terror’s horses because they did not get out of the way fast enough, and the farmhouses obliterated with the flick of a wrist because they were in the way at all, and so that passage through the fishing village, just as dead and gone as all the others, has just as much impact on you, on the protagonists, as anything, everything else that’s gone on, that goes on without even another mention until, in the climax, it’s revealed, in the course of revealing the Third Terror, that he was the one who massacred the village, they would’ve assaulted the protagonists, you see, murdered them for their boat, for their outlandishness, for the peacock tattoo, for whatever reason, and so he removed them from consideration, fft! A puzzle-piece snapped into place here at the end, but whatever satisfaction it might’ve given is lost, the entire puzzle’s indistinguishably soaked in blood, blood! and everywhere there’s screaming and the sound of blows. —Five apocalypses going off all around you here at the end, but what does it matter, really, when you’ve already seen hundreds, thousands of worlds already snuffed out? (How many of those spotlit soliloquies are minor characters relaying or reflecting on the instants just before their violently abrupt ends, or the moments immediately after?)

Thus, the Spear Cuts Through Water, a book I didn’t so much care for, and of which I am intensely, distractingly envious. It’s the only thing I’ve read by Simon Jimenez; I’m curious, now, to see what he did with his first book, The Vanished Birds. —I’m even more curious to see what he does next.

Better late than—

“Three years later, Portland’s chief of police did something unusual: He acknowledged harm caused by the Bureau’s inaccurate and incomplete press releases, and apologized.” —DEFUND is but the moderate position; truth and reconciliation nationwide are the measured response. Abolish the police before it is too late.

Bathed bread.

Fridays are Family Favorite Feast nights for us, that I make as much as possible from scratch each week, with a sort of a rotating menu; one week it’s pizza (homemade dough that’s started Thursday, sometimes Wednesday night; slow-roasted tomato sauce; pancetta or speck and mushrooms and peppers, though the kid’s always gonna want her Hawaiian variant); the next it’s burgers and fries (hand cut fries and turkey burgers, with a bit of roasted eggplant added for body, and whatever tomatoes look good, and thick rings of raw red onion and once or twice I’ve made the mayonnaise from scratch, too); the next it’s nachos (beans cooked all day in wine, and ground turkey, and I’m getting better with chilies, but the stars are the pico and the tomatillo guacamole and the seed salsa, oh my, but I don’t know that I’ll ever be at a point where I’m making my own chips, but that’s okay, we’re in Oregon, we have Juanita’s); and the fourth is a wild card slot—sometimes it’s sushi (I’ve gotten pretty good with the rice, but I am terrible at rolling), and sometimes it’s katsu sandos (homemade milk bread, and the chicken breasts are brined all afternoon before being breaded with panko from the ends of the fresh loaves), and last week it was what I usually make when it’s summertime-hot, which is pan bagnat: tomatoes grated to a pulp and smeared over the bottoms of small round loaves, and more tomatoes, sliced, and thin-sliced red onion quick-pickled in balsamic vinegar with capers and olives and an anchovy or two, and French breakfast radishes and poblano peppers and fava beans tumbled with olive oil, and oil-packed tuna, and quartered eggs just this side of jammy, and you tear out some of the crumb from the tops of the small round loaves so there’s room, and then put the tops on the bottoms and press and smash and squish, and set a weight on top to keep smashing, for a couple few hours in a cool dark place, until it’s time to pour some green wine and slice them open, and anyway I just had a leftover slice for lunch, so here, go read Talia Lavin on the pan bagnat.

Cui bono?

“Overall, I think there’s quite a bit of abdication of responsibility around what we are going to do as people’s jobs start being taken fairly aggressively. Luckily, there’s a massive population drop coming. So maybe everything is just fate and it’s gonna work out okay.” —Grimes, or c, or Claire Elise Boucher

Generation AI.

There’s a thing that sweeps through writerly social media from time to time these days, where someone or other points to the latest outrage due to generative AI, and goes on to swear they’ve never used generative AI in their works, and by God they never will, and invites any and all other authors who are and feel likewise to likewise affirm in mentions and quote-tweets and, much as yr. correspondent, Luddite that I am, would happily join in—dogpiling notions and general actions is so much more satisfying than dogpiling individuals—well: I can’t. Because I have used generative AI in the creation of a small but not unimportant part of my work.

Sort of.

Twenty three years ago, then: 10.47 UTC, on January 18th, a Friday: someone using the email address acosnasu@vygtafot.ac.uk made a post to the alt.sex.stories.d newsgroup. The subject line was, “Re: they are filling inside cold, over elder, near heavy ointments,” and here’s how it began:

One more plates will be glad wide jars. Other thin lean tickets will love hourly behind yogis. Georgette, have a rude poultice. You won’t change it. Well, Ronette never judges until Johnny attempts the poor goldsmith daily. As sneakily as John orders, you can look the unit much more angrily. There, cans talk beneath sweet markets, unless they’re bitter.

It continued in that vein for another 830-some-odd words—the output of a Markov chain: a randomly generated text where each word set down determines (mostly) the next word in the sequence. —Index a text, any text, a collection of short stories, a volume of plays, a sheaf of handwritten recipes, a year’s worth of newsletters, an archive of someone’s tweets or skeets or whatever we’re calling them these days, make an index, and, for each appearance of every word, note the word that appears next. Tot up those appearances, and then, when you want to generate a text, use the counts to weight your otherwise randome choices. Bolt on some simple heuristics, to classify the words as to parts of speech, set up clause-shapes and sentence-shells, where to put the commas and the question-marks, then wind it up and turn it loose:

The sick walnut rarely pulls James, it opens Zachary instead. We converse the sticky egg. If the bad jackets can fill undoubtably, the younger film may cook more evenings. She might irrigate freely, unless Kathy behaves pumpkins to Marian’s game.

Now, comparing a Markov chain to ChatGPT is rather like comparing a paper plane to a 747 but, I mean, here’s the thing: they both do fly. Given the Markov’s simplicity, it’s much easier to see how any meaning glimpsed in the output is entirely pareidolic; there’s no there there but what we bring to the table—even so, it’s spooky, how the flavor of the source text nonetheless seeps through, to color that illusion of intent. Given how simple Markov chains are. (ELIZA was originally just 420 lines of MAD-SLIP code, and she’s pulled Turing wool for decades.) —Anyway: somewhere around about the summer of 2006, casting about for something to conjure a spooky, surreal, quasi-divinatory mood, I hit upon the copy I’d squirreled away of that post from four years previous and, after a bit of noodling, wrote this:

The offices are dim. The cubicle walls are chin-high, a dingy, nappy brown. Jo doesn’t look at the plaques by each opening. Warm light glows from the cubicle to the right. “No,” someone’s saying. “Shadow-time’s orthogonal to pseudo-time. Plates? They’re gonna be glad wide jars again. Yeah. The car under the stale light is a familiar answer, but don’t run to the stranger’s benison – there is nothing in the end but now, and now – ”

Now, I haven’t been able to identify what originating text might’ve been so enamored of “glad” and “jars” and “benison” and “ointments,” but it’s hardly as if it’s the sum total of everything ever shelved in the Library of Congress; it’s not at all as if anyone blew through more power than France to calculate those initial weights; generating that original post twenty-three years ago didn’t light up an array of beefy chips originally designed to serve up real-time 3D graphics in videogames, burning them hot enough to boil away a 16 oz. bottle of water in the time it takes to spit out a couple-few hundred words: but. But. If someone asks whether I’ve ever used generative AI in the creation of my work, I can’t in good conscience say no. —Heck, I even went and did it again, in a callback to that particular scene, though I don’t seem to have kept a copy of the originating post for that one. It’s everywhere out there, this prehistoric gray goo, this AI slop avant la lettre, if you know where to look; weirdly charming, in a creepily hauntological sense. All those meaning-shapes, evacuated of meaning.

But, well. See. That’s not all.

Last year, for the day job, I took part in a panel discussion on “Ethical Lawyering and Generative AI.” We needed a slide deck to step through, as we explained to our jurisprudential audience the laity’s basics of this stuff that was only just then beginning to fabricate citations to cases that never existed, and a slide deck needs art, so I, well, I turned to whatever AI chatbot turducken Edge was cooking at the time (Copilot, which sits on ChatGPT, with an assist from DALL-E, I think, for the pictures)—I was curious, for one thing: I hadn’t messed around with anything like this for a half-dozen iterations, at least—back when you’d upload a picture and give it a prompt, “in the style of Van Gogh,” say, and a couple-five hours later get back an artfully distorted version of your original that, if you squinted generously in the right light, might be mistaken for something Van Gogh-adjacent. If I were to opine on this stuff, and advise, I really ought to have tinkered with it, first, and hey, I’d be doing something useful with the output of that tinkering. And but also, I wanted that slickly vapid, inanely bizarre æsthetic: smartly suited cyber-lawyers stood up by our bullet points, arguing in courtrooms of polished chancery wood and empty bright blue glass, before anonymously black-robed crash-test dummy-looking robots—we made a point of the fact that the art was AI-generated, pointing out inaccuracies and infelicities, the way it kept reaching for the averagest common denominators, the biases (whenever I asked for images of AI-enhanced lawyers, I got male figures; for AI-enhanced paralegals, female. When I asked for images of AI-enhanced public defenders? Three women and a man). It all served as something of an artful teaching moment. But: and most importantly: no artist was put out of a job, here. There was no budget for this deck but my own time, and if it wasn’t going to be AI-generated art, it was going to be whatever I could cobble together from royalty-free clip-art and my own typesetting skills.

I don’t say this as some attempt at expiation, or to provide my bona fides; I’m mostly providing context—an excuse, perhaps—for what I did next: I asked Copilot to generate some cover images for the epic.

—Not that I would ever actually begin to think about contemplating the possibility of maybe ever actually using something like that as an actual cover, dear God, no. I shoot my own covers, there’s a whole æsthetic worked out, making them is very much part of the process, I’d never look to outsource that. But generating the art for the deck had tweaked my curiosity: I get the basic idea of how it is that LLMs brute-force their generation of sloppy gobs of AI text, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how that model does what it does with images, with picture-stuff—the math just doesn’t math, I can’t get a handle on the quanta, it’s a complete mystery—and who isn’t tantalized by a mystery?

(I mean, set aside just for a moment the many and various ethical concerns, the extractive repurposing of art on a vastly unprecedented scale, without consent, the brutal exploitation of hidden human labor in reviewing and organizing and classifying the original sources, and reviewing and moderating and tweaking the output, the vast stores of capital poured into its development, warping it into a tool that consolidates money and power in hands that already have too much of both, the shocking leaps in energy consumption, the concomitant environmental degradation, the incredible inflation of our abilities to impersonate and to deceive—set all of that and more aside, I mean, it’s pretty cool, right? To just, like, get an image or four of whatever you want? Without bothering anybody?)

So I asked Copilot to generate some cover images for the epic:

Thus, the sick walnut, as it opens Zachary instead. Not terribly flattering, is it. I asked Copilot, I asked ChatGPT, I asked DALL-E to show me its take on my work, and this is the best it can bother to do?

That’s the premise of the promise these things make, after all, or rather the promise made on their behalf, by the hucksters and the barkers, the grifters and con artists sniffing around the aforementioned vast stores of capital: that there is a there, there; that what sits there knows everything it’s been shown, and understands whatever you tell it; that it can answer any questions you have, find anything you ask for, show you whatever you tell it you want to see, render up for you the very idea you have in your head—but every clause of every statement there’s untrue.

This idea, that I have in my head, is actually a constellation of ideas worked out in some detail and at great length in a form that, by virtue of having been publicly available on the web (to say nothing of having been published as eminently seizable ebooks in numerous vulnerable outlets) has always already been part of any corpus sliced and diced and analyzed to make up the unfathomably multi-dimensional arrays of tokens and associations underlying every major LLM: thus, the sum total of any and all of its ability to “know” what I point to when I point. Those pictures, then—the cover images I asked it to, ah, generate: image-shapes and trope-strokes filed away in whatever pseudo-corner of those unthinkably multi-dimensional arrays that’s closest, notionally speaking, to the pseudo-spaces made up by and enclosing the tokens generated from my books, and arranged in what’s been algorithmically determined to be the most satisfying response to my request: thus, a bathetic golden hour steeped through skyscraping towers (some rather terribly gothic, a hallmark of the Portland skyline); an assortment of the sectional furniture of swords and sword-shapes and roses and birds; a centered, backlit protagonist-figure, all so very queenly (save the one king—Lymond? Really?)—the two more modern, or at least less cod-medieval, reach for a trick that was de rigueur for a while on the covers of UF books, and numerous videogames, where the protagonist is stood with their back to us, the better to inculcate, it was thought, a sense of identification, of immersion, and also in some cases yes at least to show off a tramp stamp. There’s something queasily akin to that murmurous reunion of archetypes noted by Eco, but these clichés aren’t dancing; they’re not talking, not to each other, certainly not to us; they’re not even waiting. Just—there, in their thereless there.

So. All a bit embarrassing, really—but, to embarrass, it must have power; that power, as is usually the case these days, is found in the bullshit of its premise. I asked for cover images, but that wasn’t what I wanted; what I wanted was, I wanted to see, just for a moment, what it might all look like to someone else, outside of my head—but without the vulnerability that comes from having to ask that someone else what it is they think. That promise—our AI can do that for you—that’s intoxicating. And if it had worked?

But it didn’t, is the thing. Instead of that validating glimpse, what I got was this, this content, this output of the meanest median mode, this spinner rack of romantasy and paranormal romance julienned into a mirepoix, tuned a bit to cheat the overall timbre toward something like Pantone’s color of whatever year—oh, but that metaphor’s appallingly mixed, even for me, and anyway, they don’t really do spinner racks anymore.

747s, paper planes, the thing is that ChatGPT, LLMs, generative AI, it’s all more of a flying elephant, really, to extend the simile, and most folks when they think about it at all seem to be of the opinion that it doesn’t matter so much if it can’t loop-the-loop, or barrel roll, look at it! It’s flying! Isn’t that wild?

Thing is, it can’t so much land, either.

It’s a neat parlor trick, generative AI; really fucking expensive, but kinda sorta pretty neat? And I’d never say you can’t use it to make art, good art—I’ve seen it done, with image generation; I’ve done it myself, in my own small way, with the free-range output of Markov chains. But there’s a, not to put to fine a point on it, a human element there, noticing, selecting, altering, iterating, curating, contextualizing—the there, that needs to be there, knowing, and seeing, and showing what’s been seen. And to compare these isolated examples, these occasional possibilities, with the broadband industrial-scale generation of AI gray-goo slop currently ongoing, is to compare finding and cleaning and polishing and setting on one’s desk a pretty rock from a stream, with mountain-top removal to strip-mine the Smokies for fool’s gold.

So, there you have it: why I’m not likely to ever ask ChatGPT as such for anything ever again; why I might still mess around with stuff like Markov chains. But entirely too much faffing to fit into a tweet. Are we still calling them tweets even if they aren’t on Twitter anymore? We should still call them tweets. One of the many tells of Elon Musk’s stupidity is walking away from a brand that strong, I mean, Jesus. Like renaming Kleenex.®

While units globally tease clouds, the tags often learn towards the pretty disks. We talk them, then we totally seek Jeff and Norm’s strong tape. Why will we nibble after Beryl climbs the inner camp’s poultice? We comb the dull pear. I was smelling to attack you some of my clever farmers. She may finally open sick and plays our tired, abysmal carpenters within a mountain.

The dust left in the bore.

Author, critic, and friend of the pier Wm Henry Morris on Aspects, by John M. Ford, which post I’ll be setting aside (mostly) unread for the time being: Mr. Ford, you must understand, is one of Those Without Whom, and though I’ve had the book on the shelf for (checks) wow, a couple-three years now, it has remained unread. Something about having an unread Ford is rather as if he’s still out there, writing; certainly, having an unfinished unread Ford feels rather a lot like that. He might yet slip back and wrap it all up, and wouldn’t we feel foolish if we’d gone and assumed he wouldn’t. But. One day. And when; and then.

The Railway Bridgeman.

On a lonely string of camp cars

The lonesome bridgeman stays

After leaving his family and home

He starts out counting the days

With Monday and Tuesday made

There’s Wednesday and Thursday you know

Say we’ve made these all in succession

There’s four hours Friday to go

Suppose then it rains through Friday

Of course we must shack all day

And then we must stay over Saturday

Or else we cut our pay

So our time this week with our boys and girls

Is twenty-four hours shy

We never have time for all their games

Until again it’s goodbye

We leave there with Mother’s kindness and care

And back to our camp cars again

We start counting the days of another week

And trusting this time it won’t rain

So if we get these days as they come

We’ll be checking off Friday at eleven

And catch the first train headed for home

For there is our earthly heaven

—F.G. Manley

Sunday, January 28, 1940

“I mainly did it to frighten other writers.”

An update to this bit, about serials and such—over on Bluesky, Tade Thompson has dug up a high-res scan of Alan Moore’s Big Numbers plot that’s just about actually legible, so that’s commended to your attention; while we’re on the subject, here’s Illogical Vollume of the Mindless Ones on Big Numbers as seen through Eddie Campbell’s How to be an Artist, the latter of which I’m already going to have had reason to be mentioning here in just a little while, so stay tuned.